4 - Courtesy and Rudeness

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 June 2021

Summary

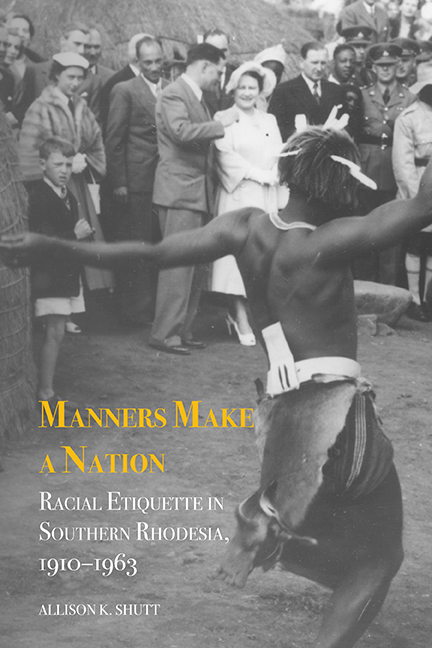

Performing and reforming racial etiquette took center stage when Southern Rhodesia joined Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland to form a Central African Federation in 1953. Although Africans in all three territories protested against the imposition of the federation and were especially suspicious of the role of Southern Rhodesian whites in the federal equation, the African middle class in Southern Rhodesia was perhaps unique in its acknowledgment of the political possibilities of “partnership,” the slogan of the federation. The problem and promise of partnership was that it was ambiguous enough to mean continued white supremacy as well as increased African participation in political, economic, and social life. As Anthony King argues, “One of the most significant aspects of partnership is how far removed the rhetoric was from that of South Africa, and so the federation could make a claim for a broadly new approach to race relations.” In contrast to South Africa, which was moving swiftly toward uncompromising white supremacy and away from the British Empire, federation politics highlighted multiracial displays and representation. By necessity, then, federation politics highlighted racial etiquette as an area of reform and controversy. Indeed, the tension between a narrow and a flexible definition of partnership provided an important entryway for African politicians who could now, more sharply than ever, point to Southern Rhodesia's exclusive racial politics as a reason for its illegitimacy.

To accelerate political change, African activists pursued an “active phase” of politics, aimed at “ending discrimination in such areas as postoffices, shops and cinemas.” Attacking the color bar was an important tactic for budding nationalists, who as late as 1958 “held on to the real possibility of a peaceful takeover of power from the white minority, particularly with the help of Britain.” This chapter begins to tell the story of the unraveling of racial etiquette by setting out the broad political context up to roughly the end of 1959, when the opening for peaceful reform closed rapidly. The first part of the chapter briefly outlines the political and economic structures that established the possibilities and limits to reforming racial etiquette in a way that would satisfy elites within the Southern Rhodesian and federal government, the British government, ordinary whites, elite Africans (mainly men), and ordinary Africans.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Manners Make a NationRacial Etiquette in Southern Rhodesia, 1910–1963, pp. 103 - 137Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2015