Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Figures

- 1 Memories of Dan Dare

- 2 Science Fiction and Selective Tradition

- 3 Science Fiction and the Cultural Field

- 4 Radio Science Fiction and the Theory of Genre

- 5 Science Fiction, Utopia and Fantasy

- 6 Science Fiction and Dystopia

- 7 When Was Science Fiction?

- 8 Where Was Science Fiction?

- 9 The Uses of Science Fiction

- Works Cited

- Index

6 - Science Fiction and Dystopia

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Figures

- 1 Memories of Dan Dare

- 2 Science Fiction and Selective Tradition

- 3 Science Fiction and the Cultural Field

- 4 Radio Science Fiction and the Theory of Genre

- 5 Science Fiction, Utopia and Fantasy

- 6 Science Fiction and Dystopia

- 7 When Was Science Fiction?

- 8 Where Was Science Fiction?

- 9 The Uses of Science Fiction

- Works Cited

- Index

Summary

In the previous chapter, we explored the relations between SF, utopia and fantasy, concluding that all three occupy positions within the contemporary global SF field and therefore contribute to the SF selective tradition. Twenty years ago, both fan critics and academics alike would have found the inclusion of fantasy much more problematic than that of utopia. Today, however, the central site of contention, albeit not to the point of exclusion, is almost certainly provided by dystopia.

The Antipathy to Dystopia

The obverse of the enthusiasm for utopia traced in chapter 5 is, in Williams, Freedman, Suvin and Jameson, something quite close to a distaste for dystopia. All four are obliged to concede, at least in passing, the obvious formal symmetries beween utopia, in the sense of eutopia, and dystopia that prompted Sargent to insist they comprise a single utopian genre. But all four are either hostile or indifferent to the most influential examples of dystopian SF. For Williams, as we've seen, SF dystopias were ‘Putropias’, predicated upon an elitist structure of feeling that counterposed ‘the isolated intellectual’ to the ‘at best brutish, at worst brutal’ masses (Williams, 2010, 15–16). For Suvin, ‘SF will be the more significant and truly relevant the more clearly it eschews … the … fashionable static dystopia of the Huxley–Orwell model’ (Suvin, 1979, 83). Elsewhere, he argues that such static dystopias are necessarily unable to do justice to ‘the immense possibilities of modern SF in an age polarized between the law of large numbers and ethical choice’ (Suvin, 1988, 106–7).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

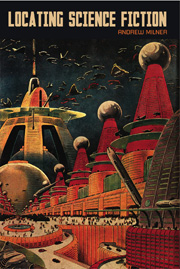

- Locating Science Fiction , pp. 115 - 135Publisher: Liverpool University PressPrint publication year: 2012