Book contents

- Islam in a Zongo

- The International African Library

- Islam in a Zongo

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- A note on style

- Glossary

- Introduction

- 1 A history of Muslim presence in Asante

- 2 Muslim presence and zongos in Asante

- 3 Those who pray together

- 4 Speaking for Islam

- 5 ‘Bōkā’

- Conclusion

- Appendix

- References

- Other sources

- Index

- Titles in the Series

- References

- Islam in a Zongo

- The International African Library

- Islam in a Zongo

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- A note on style

- Glossary

- Introduction

- 1 A history of Muslim presence in Asante

- 2 Muslim presence and zongos in Asante

- 3 Those who pray together

- 4 Speaking for Islam

- 5 ‘Bōkā’

- Conclusion

- Appendix

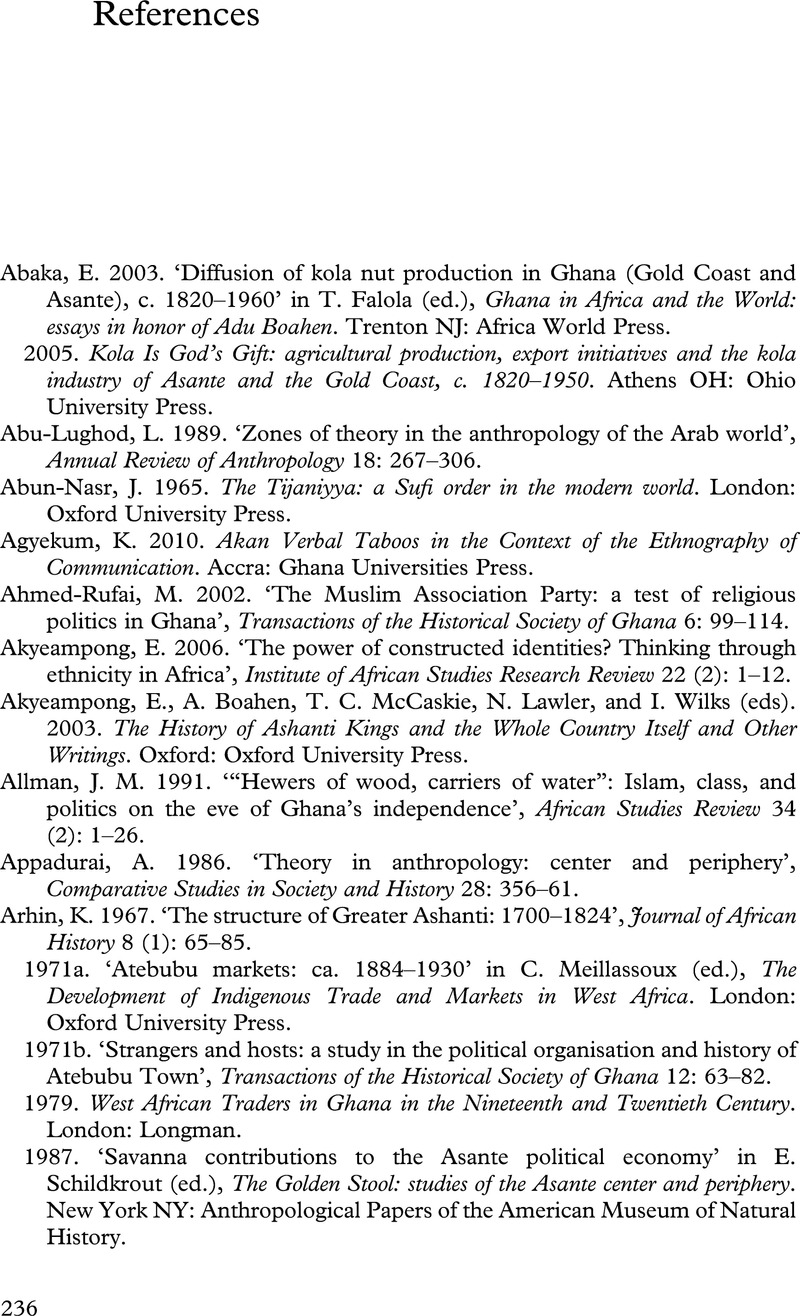

- References

- Other sources

- Index

- Titles in the Series

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Islam in a ZongoMuslim Lifeworlds in Asante, Ghana, pp. 236 - 255Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2021