Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword: Let It Get into You

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: On Intimate Entanglements

- Chapter One Yusef 's Breath: Jazz Love, Cross-Racial Identification, and Paying Dues

- Chapter Two Three Reflections, with Epilogue

- Chapter Three Modulating Flawed Bodies: Intimate Acoustemologies, Chronic Pain, and Ethnographic Pianism

- Chapter Four Performing Desire: Race, Sex, and the Ethnographic Encounter

- Chapter Five Thick Descriptions

- Chapter Six Entering the Lives of Others: Entangled Intimacies, Trauma, and Performance

- Chapter Seven Ethnomusicological Empathy: Excavating a Black Graduate Student’s Heartland

- Chapter Eight Ethnomusicological Becoming: Deep Listening as Erotics in the Field

- Chapter Nine Mirror Dancing in Congo: Reflections on Fieldwork as Blanche Neige

- Chapter Ten Ethnography and its Double(s): Theorizing the Personal with Jews in Ghana

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

Chapter Six - Entering the Lives of Others: Entangled Intimacies, Trauma, and Performance

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 January 2024

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword: Let It Get into You

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: On Intimate Entanglements

- Chapter One Yusef 's Breath: Jazz Love, Cross-Racial Identification, and Paying Dues

- Chapter Two Three Reflections, with Epilogue

- Chapter Three Modulating Flawed Bodies: Intimate Acoustemologies, Chronic Pain, and Ethnographic Pianism

- Chapter Four Performing Desire: Race, Sex, and the Ethnographic Encounter

- Chapter Five Thick Descriptions

- Chapter Six Entering the Lives of Others: Entangled Intimacies, Trauma, and Performance

- Chapter Seven Ethnomusicological Empathy: Excavating a Black Graduate Student’s Heartland

- Chapter Eight Ethnomusicological Becoming: Deep Listening as Erotics in the Field

- Chapter Nine Mirror Dancing in Congo: Reflections on Fieldwork as Blanche Neige

- Chapter Ten Ethnography and its Double(s): Theorizing the Personal with Jews in Ghana

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

Summary

Moving from silence into speech is for the oppressed, the colonized, the exploited, and those who stand and struggle side by side a gesture of defiance that heals, that makes new life and new growth possible. It is that act of speech, of ‘talking back,’ that is no mere gesture of empty words, that is the expression of our movement from object to subject— the liberated voice

—bell hooksSε woankasa wo tiri ho a, yeyi wo ayi bͻne

[If you don't talk about your head, you get a bad haircut]

—Ghanaian Akan proverbBloomington-Normal, Illinois. June 5, 2020. My friend and I are on our morning walk on the Constitution Trail. We are discussing many topics, including aging and exercising, hypertension, music, Black Lives Matter, the police. We spend a long time talking about the protests following the killing of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery. I tell him that true to the Ghanaian Akan saying, ͻhohoͻ ani tuatua hͻ kwa, “The visitor's eyes do not perceive,” as a female Ghanaian immigrant it took me decades to understand the effect of race relations on Black bodies. Like some Africans who come to America, I tell him, I was very naive and oblivious to discourses on race, racial politics, and anti-Blackness, and how those affect Black lives in America. I saw, but I did not see. I tell him that my journey, most of which involved Black women, had been long and fraught with tension and misunderstanding. He asks, “What was it like for you?” He asks for specifics, for some key moments on that journey. I pause. I reflect.

As a Ghanaian Akan female scholar, performer, and a mother living in America, my body is on edge. The effects of white-body supremacy that live and breathe in my own body, the result of my experiences as a Ghanaian woman living in America, have me trauma ghosted, that recurrent or pervasive sense that danger is around the corner, or something terrible is going to happen. I police what I say to white people, upholding their emotional patriarchy (Armah). Our Ghanaian Akan Elders say, Nea ͻwͻ aka no suro sonsono, “She who has been bitten by a snake is afraid of a worm.”

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

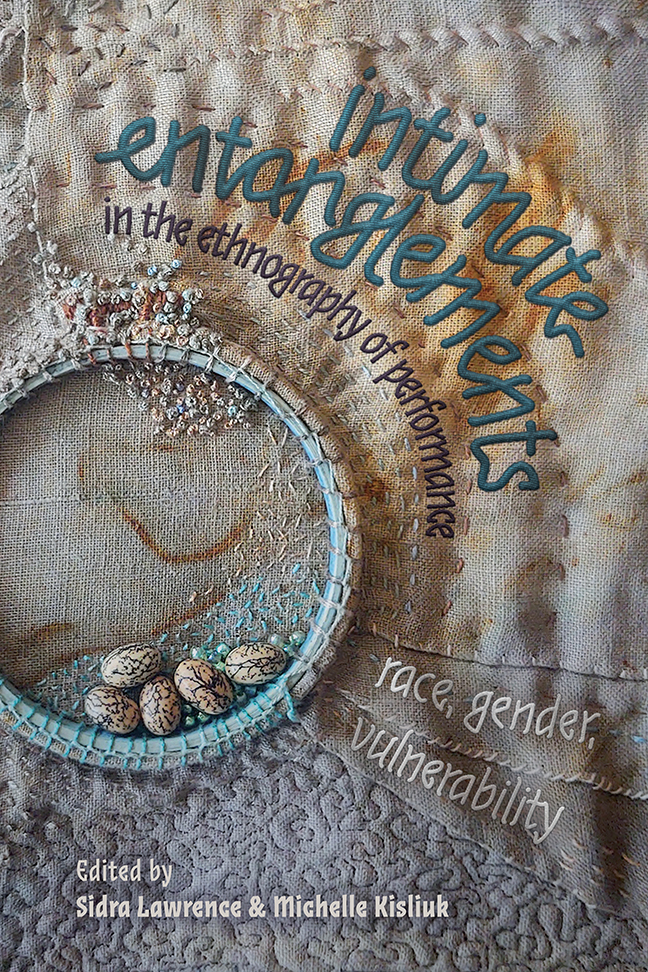

- Intimate Entanglements in the Ethnography of PerformanceRace, Gender, Vulnerability, pp. 114 - 149Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2023