Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Digital Facsimiles of Frequently Cited Manuscripts

- The Contents of Oxford, Bodleian Library, Digby 86

- Note on the Presentation of MS Digby 86 Texts

- Introduction

- 1 Fellow Travellers with Saint Nicholas

- 2 Anglo-Norman Religious Instruction in MS Digby 86: Echoes of Lateran IV

- 3 Latin and Vernacular Prayers in MS Digby 86

- 4 Science, Medicine, Prognostication: MS Digby 86 as a Household Almanac

- 5 Literary Therapeutics: Experimental Knowledge in MS Digby 86

- 6 Petrus Alfonsi, the Disciplina clericalis and Le Romaunz Peres Aunfour of MS Digby 86

- 7 Misogyny in MS Digby

- 8 Gender Trouble? Fabliau and Debate in MS Digby 86

- 9 The Middle English Poetry of MS Digby 86

- 10 MS Digby 86 and Thirteenth-Century Scribal Poetics

- 11 The Scarlet Letter: Experimentation, Design and Copying Practice in the Coloured Capitals of MS Digby 86

- 12 Below Malvern: MS Digby 86, the Grimhills and the Underhills in their Regional and Social Context

- Bibliography

- Index of Manuscripts Cited

- General Index

- Manuscript Culture in the British Isles

7 - Misogyny in MS Digby

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 October 2019

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Digital Facsimiles of Frequently Cited Manuscripts

- The Contents of Oxford, Bodleian Library, Digby 86

- Note on the Presentation of MS Digby 86 Texts

- Introduction

- 1 Fellow Travellers with Saint Nicholas

- 2 Anglo-Norman Religious Instruction in MS Digby 86: Echoes of Lateran IV

- 3 Latin and Vernacular Prayers in MS Digby 86

- 4 Science, Medicine, Prognostication: MS Digby 86 as a Household Almanac

- 5 Literary Therapeutics: Experimental Knowledge in MS Digby 86

- 6 Petrus Alfonsi, the Disciplina clericalis and Le Romaunz Peres Aunfour of MS Digby 86

- 7 Misogyny in MS Digby

- 8 Gender Trouble? Fabliau and Debate in MS Digby 86

- 9 The Middle English Poetry of MS Digby 86

- 10 MS Digby 86 and Thirteenth-Century Scribal Poetics

- 11 The Scarlet Letter: Experimentation, Design and Copying Practice in the Coloured Capitals of MS Digby 86

- 12 Below Malvern: MS Digby 86, the Grimhills and the Underhills in their Regional and Social Context

- Bibliography

- Index of Manuscripts Cited

- General Index

- Manuscript Culture in the British Isles

Summary

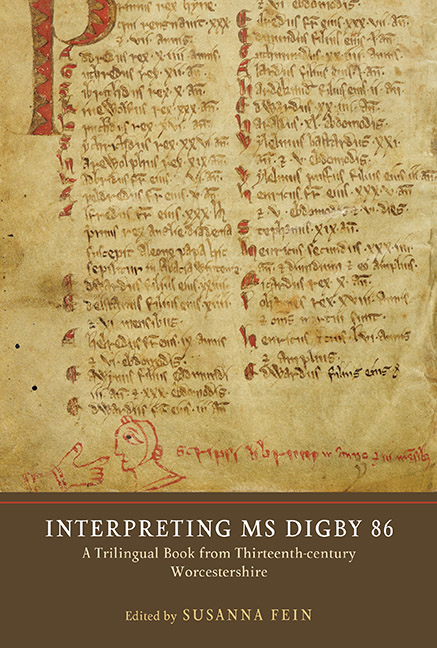

IN the lower margin on the recto side of what is now folio 80 of Oxford, BodL, MS Digby 86, the head of a woman has been drawn in profile and the word ‘femina’ (woman) written beside it (Fig. 1). The hand that wrote ‘femina’ here is the same as the one that has written almost all of the contents of Digby 86, and the woman's head seems to have been drawn by him too, not least because it is in the same ink as its caption. The two columns of text on fol. 80r make no reference to any woman, and so the scribe's drawing is not an illustration of anything that the page says. ‘Woman’ seems to have been on the Digby scribe's mind for other reasons. Perhaps she was there already – but a large amount of the material that the scribe copied later in his manuscript encouraged him to think of her. It also encouraged him to think negatively of her. This may have been why ‘femina’ is depicted in his drawing with long, loose, flowing hair. Although the scribe may have thought of long hair simply as something that distinguished a woman from a man, in medieval iconography long, unbound hair often denotes rampant sexuality, which was frequently associated with women in the Middle Ages, and is associated with them in texts that the Digby scribe copied into his manuscript. It is worth noting that in the lower margin of the facing page in his book (fol. 79v), the scribe has drawn the head of a man (‘homo’) with his hair tightly bound in a headdress (Fig. 2).

The material that the Digby scribe has copied above his drawing of ‘femina’ is from Le Romaunz Peres Aunfour (a versified French translation of Petrus Alfonsi's Disciplina clericalis), in which a father tells his son a large number of cautionary tales. Several of these tales warn the son to beware of ‘femme’. One tells how when a woman's husband returned unexpectedly from his vineyard with an injured eye, she covered up his other eye so that her lover could escape. When the husband of another woman went on pilgrimage, he entrusted her to her mother so that she ‘would not do anything silly’ (‘ne foleast’; fol. 83ra). But the mother colluded in her daughter's adultery and enabled the escape of her lover when the husband returned.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Interpreting MS Digby 86A Trilingual Book from Thirteenth-Century Worcestershire, pp. 113 - 129Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2019