Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Glossary

- 1 JUG: Scarborough, Yorkshire, c. 1250–1300

- 2 DRINKING POT: probably English, c. 1545–60

- 3 FLAGON: probably Derbyshire or Staffordshire, c. 1630–60

- 4 BOTTLE: Christian Wilhelm, Southwark, 1628

- 5 DISH: Southwark, 1651

- 6 JUG: probably Harlow, Essex, c. 1630–60

- 7 TWO-HANDLED TYG: probably Henry Ifield, Wrotham, Kent, 1668

- 8 TULIP CHARGER: London, 1661

- 9 ‘NOBODY’: London, 1675

- 10 DISH: Thomas Toft, Staffordshire, c. 1662–85

- 11 POSSET POT AND SALVER: London or Bristol, 1685 and 1686

- 12 CISTERN: London, perhaps Norfolk House, Lambeth, c. 1680–1700

- 13 BOTTLE: John Dwight, Fulham, c. 1689–94

- 14 MUG: David and John Phillip Elers, probably Bradwell Wood, Staffordshire, c. 1691–8

- 15 JUG: Staffordshire c. 1680–1710

- 16 COVERED CUP WITH FOUR HANDLES AND A WHISTLE: probably South Wiltshire, 1718

- 17 DISH: Samuel Malkin, Burslem, c. 1720–30

- 18 SIX CHINOISERIE TILES: Bristol or London, c. 1720–50

- 19 PUNCH BOWL AND COVER: Liverpool, 1724

- 20 HUNTING MUG: probably Vauxhall Pottery, 1730

- 21 TWO-HANDLED LOVING CUP: probably Nottingham or Crich, 1739

- 22 MILK JUG AND TEAPOT: Staffordshire, c. 1725–45 and c. 1740–50

- 23 PEW GROUP: Staffordshire, c. 1740–50

- 24 BEAR JUG OR JAR: Staffordshire, c. 1740–70

- 25 CAMEL AND MONKEY OR SQUIRREL TEAPOTS: Staffordshire, c. 1750–5

- 26 JUG: Staffordshire, c. 1755–65

- 27 DISH: Liverpool, c. 1755–60

- 28 TEABOWL, SAUCER AND COFFEE POT: Staffordshire, c. 1750–65

- 29 COFFEE POT: Staffordshire, 1760

- 30 TEAPOT: probably Josiah Wedgwood, Burslem, c. 1759–66

- 31 TUREEN: Staffordshire, c. 1760–5

- 32 TEAPOT: Josiah Wedgwood, Etruria, printed in Liverpool by Guy Green, c. 1775–80

- 33 JUG: Yorkshire, 1780

- 34 CENTREPIECE: probably Leeds Pottery, Yorkshire, c. 1780–1800

- 35 STGEORGE AND THE DRAGON: Staffordshire, c. 1780–1800

- 36 TOBY JUG: c. 1790–1810

- 37 DEMOSTHENES: Enoch Wood, Burslem, c. 1790–1810

- 38 ERASMUS DARWINS PORTLAND VASE COPY: Josiah Wedgwood, Etruria, Staffordshire, c. 1789–90

- 39 TEAPOT: probably Sowter & Co., Mexborough, Yorkshire, c. 1800–11

- 40 OBELISK: Bristol Pottery, Temple Back, Bristol, 1802

- 41 DINNER PLATE: Spode, Stoke-on-Trent, c. 1806–33

- 42 GARNITURE OF FIVE COVERED VASES: Richard Woolley, Lane End Longton, c. 1810–12

- 43 JUG: probably Staffordshire or Liverpool, c. 1810–20

- 44 DISH: Leeds Pottery, Yorkshire, C. 1815-20

- 45 ‘PERSWAITION’: probably john Walton, Burslem, c. 1815–25

- 46 VASE AND COVER WITH PAGODA FINIAL Charles James Mason & Co., Fenton Stone Works, Lane Delph, Fenton, c. 1826–45

- 47 FLASK IN THE SHAPE OF A GIRL HOLDING A DOVE: James Bourne & Co., Denby or Codnor Park, c. 1835–40

- 48 THE ‘BULRUSH’ WATER JUG: Ridgway & Abington, Hanley, c. 1848–60

- 49 POT-LID: T.J. & J. Mayer, Dale Hall Pottery Longport, Burslem, 1851

- 50 EWER AND BASIN: Minton, Stoke-on-Trent, 1856

- 51 THE PRINCESS ROYAL AND PRINCE FREDERICK WILLIAM OF PRUSSIA: Staffordshire, 1857

- 52 JUG: John Phillips Hoyle, Bideford, North Devon, 1857

- 53 GIANT TEAPOT: probably Church Gresley or Woodville, Derbyshire, 1882

- 54 FLAGON: Doulton & Co., Lambeth; decorated by George Tinworth, 1874

- 55 TILE PICTURE: William De Morgan & Co., Sands End Pottery, Fulham, c. 1888–97

- 56 OWL: Martin Brothers, Southall, modelled by Robert Wallace Martin, September, 1903

- 57 HOP JUG: Belle Vue Pottery, Rye, Sussex, 1899

- 58 VASE: designed by William Moorcroft for James Macintyre & Co., Washington Works, Burslem, and made there or at Cobridge c. 1911–13

- 59 DISH: Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, Etruria; decorated by Alfred Powell, c. 1908

- 60 JUG: Royal Doulton, Burslem, c. 1930–40

- 61 DINNER PLATE: Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, Barlaston, 1955

- 62 PAGODA-LIDDED BOWL: Bernard Leach, StIves, Cornwall, c. 1960–5

- 63 VASE: Hans Coper, c. 1966–70

- 64 DEEP-SIDED BOWL ON A HIGH FOOT: Alan Caiger-Smith, Aldermaston Pottery, 1981

14 - MUG: David and John Phillip Elers, probably Bradwell Wood, Staffordshire, c. 1691–8

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 September 2010

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Glossary

- 1 JUG: Scarborough, Yorkshire, c. 1250–1300

- 2 DRINKING POT: probably English, c. 1545–60

- 3 FLAGON: probably Derbyshire or Staffordshire, c. 1630–60

- 4 BOTTLE: Christian Wilhelm, Southwark, 1628

- 5 DISH: Southwark, 1651

- 6 JUG: probably Harlow, Essex, c. 1630–60

- 7 TWO-HANDLED TYG: probably Henry Ifield, Wrotham, Kent, 1668

- 8 TULIP CHARGER: London, 1661

- 9 ‘NOBODY’: London, 1675

- 10 DISH: Thomas Toft, Staffordshire, c. 1662–85

- 11 POSSET POT AND SALVER: London or Bristol, 1685 and 1686

- 12 CISTERN: London, perhaps Norfolk House, Lambeth, c. 1680–1700

- 13 BOTTLE: John Dwight, Fulham, c. 1689–94

- 14 MUG: David and John Phillip Elers, probably Bradwell Wood, Staffordshire, c. 1691–8

- 15 JUG: Staffordshire c. 1680–1710

- 16 COVERED CUP WITH FOUR HANDLES AND A WHISTLE: probably South Wiltshire, 1718

- 17 DISH: Samuel Malkin, Burslem, c. 1720–30

- 18 SIX CHINOISERIE TILES: Bristol or London, c. 1720–50

- 19 PUNCH BOWL AND COVER: Liverpool, 1724

- 20 HUNTING MUG: probably Vauxhall Pottery, 1730

- 21 TWO-HANDLED LOVING CUP: probably Nottingham or Crich, 1739

- 22 MILK JUG AND TEAPOT: Staffordshire, c. 1725–45 and c. 1740–50

- 23 PEW GROUP: Staffordshire, c. 1740–50

- 24 BEAR JUG OR JAR: Staffordshire, c. 1740–70

- 25 CAMEL AND MONKEY OR SQUIRREL TEAPOTS: Staffordshire, c. 1750–5

- 26 JUG: Staffordshire, c. 1755–65

- 27 DISH: Liverpool, c. 1755–60

- 28 TEABOWL, SAUCER AND COFFEE POT: Staffordshire, c. 1750–65

- 29 COFFEE POT: Staffordshire, 1760

- 30 TEAPOT: probably Josiah Wedgwood, Burslem, c. 1759–66

- 31 TUREEN: Staffordshire, c. 1760–5

- 32 TEAPOT: Josiah Wedgwood, Etruria, printed in Liverpool by Guy Green, c. 1775–80

- 33 JUG: Yorkshire, 1780

- 34 CENTREPIECE: probably Leeds Pottery, Yorkshire, c. 1780–1800

- 35 STGEORGE AND THE DRAGON: Staffordshire, c. 1780–1800

- 36 TOBY JUG: c. 1790–1810

- 37 DEMOSTHENES: Enoch Wood, Burslem, c. 1790–1810

- 38 ERASMUS DARWINS PORTLAND VASE COPY: Josiah Wedgwood, Etruria, Staffordshire, c. 1789–90

- 39 TEAPOT: probably Sowter & Co., Mexborough, Yorkshire, c. 1800–11

- 40 OBELISK: Bristol Pottery, Temple Back, Bristol, 1802

- 41 DINNER PLATE: Spode, Stoke-on-Trent, c. 1806–33

- 42 GARNITURE OF FIVE COVERED VASES: Richard Woolley, Lane End Longton, c. 1810–12

- 43 JUG: probably Staffordshire or Liverpool, c. 1810–20

- 44 DISH: Leeds Pottery, Yorkshire, C. 1815-20

- 45 ‘PERSWAITION’: probably john Walton, Burslem, c. 1815–25

- 46 VASE AND COVER WITH PAGODA FINIAL Charles James Mason & Co., Fenton Stone Works, Lane Delph, Fenton, c. 1826–45

- 47 FLASK IN THE SHAPE OF A GIRL HOLDING A DOVE: James Bourne & Co., Denby or Codnor Park, c. 1835–40

- 48 THE ‘BULRUSH’ WATER JUG: Ridgway & Abington, Hanley, c. 1848–60

- 49 POT-LID: T.J. & J. Mayer, Dale Hall Pottery Longport, Burslem, 1851

- 50 EWER AND BASIN: Minton, Stoke-on-Trent, 1856

- 51 THE PRINCESS ROYAL AND PRINCE FREDERICK WILLIAM OF PRUSSIA: Staffordshire, 1857

- 52 JUG: John Phillips Hoyle, Bideford, North Devon, 1857

- 53 GIANT TEAPOT: probably Church Gresley or Woodville, Derbyshire, 1882

- 54 FLAGON: Doulton & Co., Lambeth; decorated by George Tinworth, 1874

- 55 TILE PICTURE: William De Morgan & Co., Sands End Pottery, Fulham, c. 1888–97

- 56 OWL: Martin Brothers, Southall, modelled by Robert Wallace Martin, September, 1903

- 57 HOP JUG: Belle Vue Pottery, Rye, Sussex, 1899

- 58 VASE: designed by William Moorcroft for James Macintyre & Co., Washington Works, Burslem, and made there or at Cobridge c. 1911–13

- 59 DISH: Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, Etruria; decorated by Alfred Powell, c. 1908

- 60 JUG: Royal Doulton, Burslem, c. 1930–40

- 61 DINNER PLATE: Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, Barlaston, 1955

- 62 PAGODA-LIDDED BOWL: Bernard Leach, StIves, Cornwall, c. 1960–5

- 63 VASE: Hans Coper, c. 1966–70

- 64 DEEP-SIDED BOWL ON A HIGH FOOT: Alan Caiger-Smith, Aldermaston Pottery, 1981

Summary

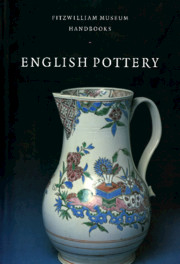

Red dry-bodied stoneware, with turned bands and mould-applied decoration of chrysanthemum sprays, three snails and a Merry Andrew. Height 10.1 cm. C.454–1928.

Red stoneware originated in China and by about 1670 it was being imported from Yixing by the Dutch. Teapots were especially prized because of their heat-retaining properties, and were imitated at Delft from the early 1670s. The first person to make red stoneware in England was probably John Dwight, whose patent of 1684 included ‘opacous- redd and darke coloured Porcellane or China’. Some fragments of redware were found during excavations at the Fulham pottery, but it is not certain that Dwight produced it on a commercial scale. Late seventeenth-century redware is generally attributed to David and John Phillip Elers, immigrants of German origin who had settled in London before 1686, when David was recorded as a shop owner near St Clement's church. They were silversmiths, but David claimed to have learned the art of stoneware manufacture at Cologne.

David Elers was probably making pottery in Staffordshire by 1691, and in 1693 the brothers were recorded as making red teapots there and at Vauxhall. This resulted in them being sued by John Dwight for infringement of his patent. After reaching an agreement with him, the Elers continued their business at Bradwell Wood, near Newcastle-under-Lyme, until 1698 when they moved back to Vauxhall. By 1700 they were bankrupt and both turned to china dealing, John Phillip in Dublin and David in London.

Apart from teapots, the Elers are credited with beakers, globular and straight-sided mugs, and tankards. Some of these were slip-cast and turned on a lathe to smooth their contours or to create raised bands on the exterior.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- English Pottery , pp. 38 - 39Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 1995