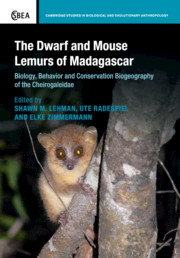

The Dwarf and Mouse Lemurs of Madagascar

The Dwarf and Mouse Lemurs of Madagascar Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Foreword

- Part I Cheirogaleidae: evolution, taxonomy, and genetics

- Part II Methods for studying captive and wild cheirogaleids

- Part III Cheirogaleidae: behavior and ecology

- Part IV Cheirogaleidae: sensory ecology, communication, and cognition

- Part V Cheirogaleidae: conservation biogeography

- Index

- Plate section

- References

Foreword

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 March 2016

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Foreword

- Part I Cheirogaleidae: evolution, taxonomy, and genetics

- Part II Methods for studying captive and wild cheirogaleids

- Part III Cheirogaleidae: behavior and ecology

- Part IV Cheirogaleidae: sensory ecology, communication, and cognition

- Part V Cheirogaleidae: conservation biogeography

- Index

- Plate section

- References

Summary

The group of primates of the subfamily Cheirogaleidae (Malagasy primates; family Lemuridae) are among the most interesting animals alive today. They originated approximately 25–30 million years ago; they are all Malagasy and are nocturnal in activity; they include the smallest of the living primates; they include the only known obligate hibernators within the primates; and, especially like the other nocturnal primate species, their taxonomy has been greatly expanded within the past two decades (Yoder et al., Chapter 1; Groves, Chapter 2).

This book, The Dwarf and Mouse Lemurs of Madagascar: Biology, Behavior and Conservation Biogeography of the Cheirogaleidae, is edited by Shawn M. Lehman, Ute Radespiel, and Elke Zimmermann. It examines their evolution, taxonomy, and genetics; the methods used for studying captive and wild cheirogaleids; their behavior and ecology; the sensory ecology, communication system, and cognition of these animals; and their conservation biology. The book contains 27 chapters with an array of over 40 exceptional international authors, specializing in anthropology, biology, psychology, veterinary medicine, and primatology.

When research on the ecology and behavior of the Malagasy primates was just beginning, over 50 years ago, Jean-Jacques Petter and Arlette Petter-Rousseaux knew of only six species in three genera of cheirogaleids (Petter, 1962; Petter-Rousseaux, 1967). Now, over 30 species in 5 genera are recognized today. Changes have occurred because of “traditional” (morphological) taxonomic research. This has been related, since the mid-1980s, mainly to specific-mate recognition systems of the vocalizations of different nocturnal primate species. However, since around 2000, DNA sequencing has played a great role in recognizing different species (Yoder et al., Chapter 1; Groves, Chapter 2).

Biologists have found that the molecular and morphological diversity related to biogeographic patterns is more complex in Cheirogaleidae than was previously thought. Related to a number of factors during their evolution, the family had initial genus-level divergence in the Oligocene–Miocene epochs, followed by a widespread Pliocene–Pleistocene species-level radiation. Louis, Jr. and Lei Chapter 3) argue that there was a basal split within Cheirogaleidae at approximately 29 million years ago: with Phaner splitting at 28.17 million years ago, Cheirogaleus at 23.77 million years ago, Allocebus at 17.94 million years ago, and lastly Mirza from Microcebus at 14.81 million years ago.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Dwarf and Mouse Lemurs of MadagascarBiology, Behavior and Conservation Biogeography of the Cheirogaleidae, pp. xv - xxPublisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2016