Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

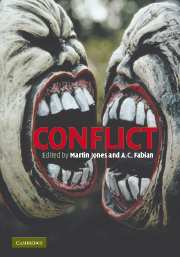

- Introduction: Arenas of conflict

- 1 Intrapersonal conflict

- 2 Sex differences in mind

- 3 Why apes and humans kill

- 4 The roots of warfare

- 5 Conflict in the Middle East

- 6 Observing conflict

- 7 Conflict and labour

- 8 Life in a violent universe

- Notes on the contributors

- Index

7 - Conflict and labour

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 August 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Arenas of conflict

- 1 Intrapersonal conflict

- 2 Sex differences in mind

- 3 Why apes and humans kill

- 4 The roots of warfare

- 5 Conflict in the Middle East

- 6 Observing conflict

- 7 Conflict and labour

- 8 Life in a violent universe

- Notes on the contributors

- Index

Summary

Conflict and labour are inextricably linked. But the link is not straight-forward, and nor are the symptoms of conflict. This essay is concerned with how both the link and the symptoms have changed. And the change has been very substantial. Strike levels are currently remarkably low in historical terms, both in Britain and worldwide. But despite this, I shall argue that the significance of conflict to the relationship between employer and employee is undiminished. Indeed, the implication of my argument is that the fall in strikes is itself a matter for concern.

Let me start by emphasizing two sharply contrasting aspects of labour. The image of industrial conflict with which anyone over the age of about thirty will be familiar is one of rowdy picket lines, locked factory gates, indignant banners and even police in riot gear. But it is now twenty years since the bitter national coal-miners' strike ended. That year-long dispute, which split and broke a once-powerful trade union, both symbolized and hastened the end of a period of British history during which overt labour conflict was rarely out of the headlines.

Contrast that with a far more familiar employment scene in Britain in the twenty-first century, to be found, for example, anywhere in the Fens of Eastern England; one of recent migrant workers, tending, picking and packing vegetables. They come from all over the world: Lithuanians, Poles, Chinese, Brazilians, Portuguese, Kurds and so on. Some are directly employed by the farmers, more are employed through gang-master agencies.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Conflict , pp. 125 - 143Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2006