Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- 1 Ming government

- 2 The Ming fiscal administration

- 3 Ming law

- 4 The Ming and Inner Asia

- 5 Sino-Korean tributary relations under the Ming

- 6 Ming foreign relations: Southeast Asia

- 7 Relations with maritime Europeans, 1514–1662

- 8 Ming China and the emerging world economy, c. 1470–1650

- 9 The socio-economic development of rural China during the Ming

- 10 Communications and commerce

- 11 Confucian learning in late Ming thought

- 12 Learning from Heaven: the introduction of Christianity and other Western ideas into late Ming China

- 13 Official religion in the Ming

- 14 Ming Buddhism

- 15 Taoism in Ming culture

- Bibliographic notes

- Bibliography

- Glossary-Index

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 March 2008

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- 1 Ming government

- 2 The Ming fiscal administration

- 3 Ming law

- 4 The Ming and Inner Asia

- 5 Sino-Korean tributary relations under the Ming

- 6 Ming foreign relations: Southeast Asia

- 7 Relations with maritime Europeans, 1514–1662

- 8 Ming China and the emerging world economy, c. 1470–1650

- 9 The socio-economic development of rural China during the Ming

- 10 Communications and commerce

- 11 Confucian learning in late Ming thought

- 12 Learning from Heaven: the introduction of Christianity and other Western ideas into late Ming China

- 13 Official religion in the Ming

- 14 Ming Buddhism

- 15 Taoism in Ming culture

- Bibliographic notes

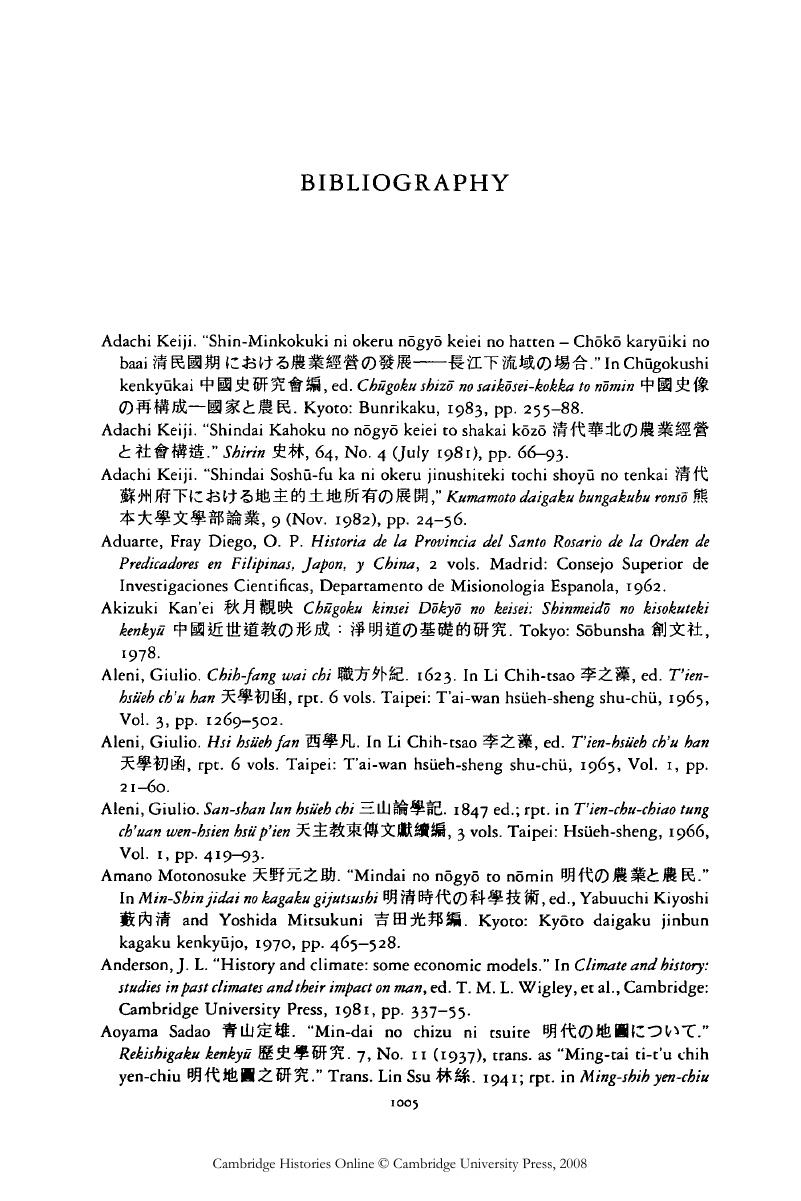

- Bibliography

- Glossary-Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Cambridge History of China , pp. 1005 - 1083Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 1998