Book contents

- The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare’s Language

- The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare’s Language

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Part I Basic Elements

- Part II Shaping Contexts

- Part III New Technologies

- Part IV Contemporary Sites for Language Change

- Appendix Glossary of Rhetorical Figures

- Further Reading

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- Cambridge Companions to…

- References

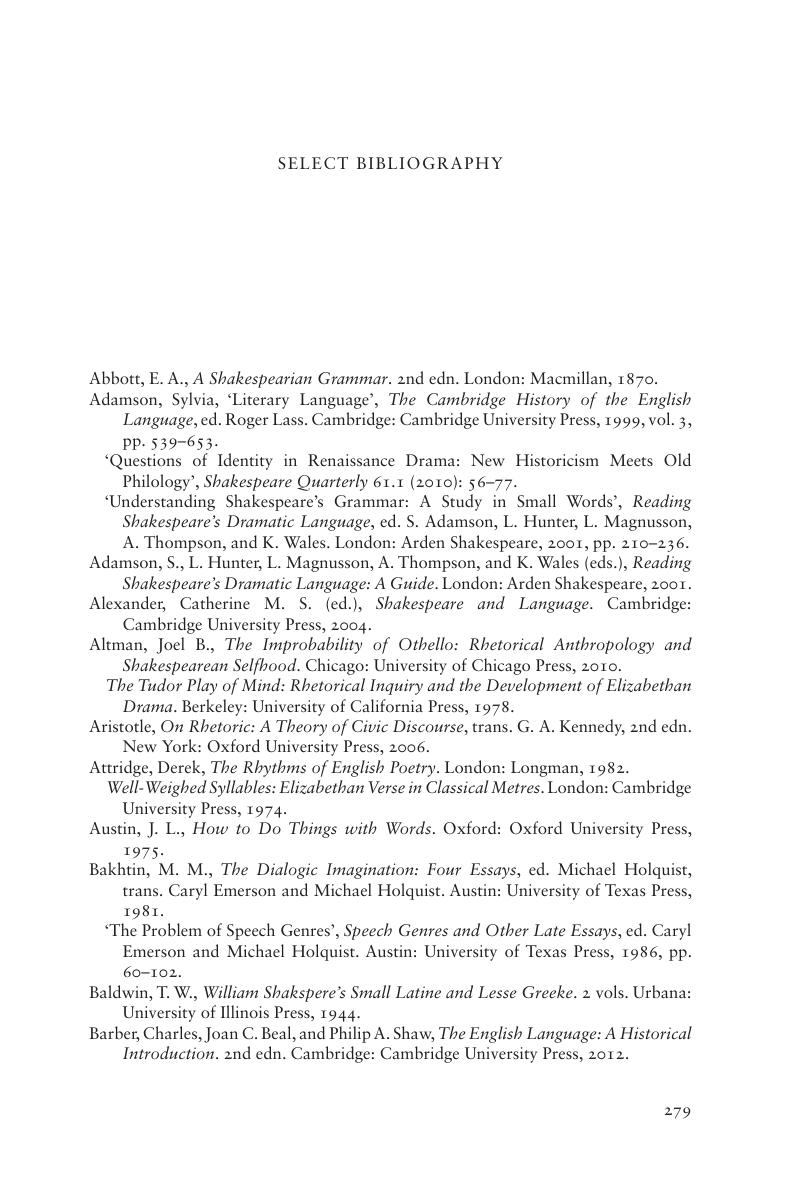

Select Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 July 2019

- The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare’s Language

- The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare’s Language

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Part I Basic Elements

- Part II Shaping Contexts

- Part III New Technologies

- Part IV Contemporary Sites for Language Change

- Appendix Glossary of Rhetorical Figures

- Further Reading

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- Cambridge Companions to…

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's Language , pp. 279 - 286Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2019