Book contents

- Avant-Garde on Record

- Avant-Garde on Record

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Ping-Pong and Its Discontents

- 3 Doubles, Rhymes and Groups in Stereo

- 4 Transnational Multiorchestralism

- 5 The Monumental Stereo of Son et Lumière

- 6 Phonographic Spaces: Circling San Marco, Navigating Niagara

- 7 Open Works Locked into Grooves

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

- Music Since 1900

- References

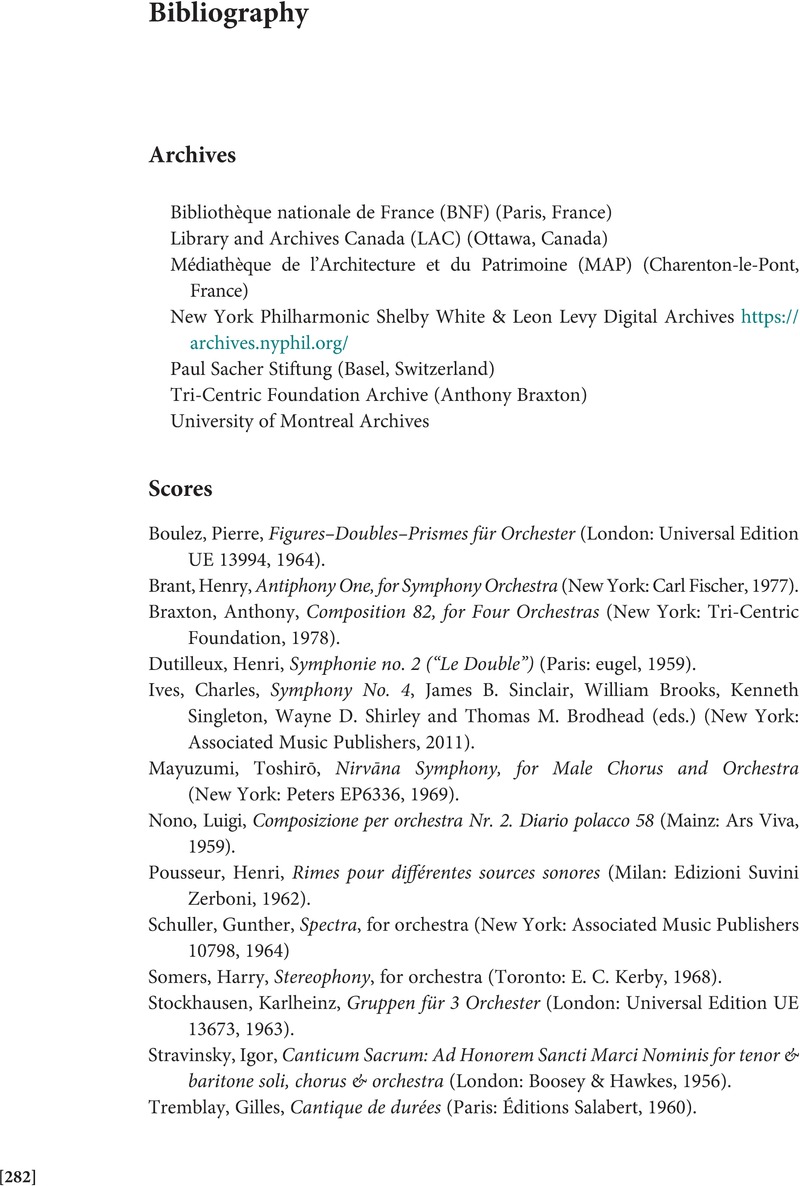

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 January 2024

- Avant-Garde on Record

- Avant-Garde on Record

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Ping-Pong and Its Discontents

- 3 Doubles, Rhymes and Groups in Stereo

- 4 Transnational Multiorchestralism

- 5 The Monumental Stereo of Son et Lumière

- 6 Phonographic Spaces: Circling San Marco, Navigating Niagara

- 7 Open Works Locked into Grooves

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

- Music Since 1900

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Avant-Garde on RecordMusical Responses to Stereos, pp. 282 - 310Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2023