I play board games often, and Dungeons and Dragons most weeks with a group of friends I got together, I host and run the games which is fun because the host (aka the Dungeon Master [DM] or the Game Master) is a part of the group but also the leader but not a part of team. The role and dynamic is hard to explain but the important part is that it gives a structural reason for me to be a part of the group without feeling fully part of it and the same as everyone else – the team works together to overcome the obstacles, puzzles, challenges and scenarios that the DM designs (all as part of a story you create together), which makes it natural that I’m not a part of the “how do we beat this puzzle” conversations, I’m not a part of the problem-solving because I’m the one to set the problems. This means that I am a valued member of the group – the most valuable because sessions can’t physically happen without me. I know I’m important to the group, that I matter, because I’m needed, and I know I’m liked because otherwise they wouldn’t want to come and play. But I’m still not in the thick of it, part of the team – which disguises the constant feelings I have, as an autistic person, of being a perpetual outsider. I think being raised NT [neurotypical] when I’m not, and also masking, in a neurotypical world has given me a powerful case of imposters’ syndrome, so I never really feel included, welcome, or valued by a group of people unless I’m totally absorbed in something (e.g. a game) or I’ve been told that the group wants me there and values me. So as DM I know that I have to act, conceal my reactions to people suggesting the correct solution or a totally ridiculous and silly solution to a puzzle or problem, because my pokerface is important to the game. So masking is normal. I know I have to prep things ahead of time and that the sessions make my brain tired because it’s intense decision making, so taking breaks and finishing when *I* need to is normal and accepted. I’m a part of the group, but as DM I’m not part of the team – so my feelings of being involved but not always included are right, accurate, and also totally normal and not a reflection on me or on whether or not I’m wanted there. There are a lot of ways that DnD feels like the perfect environment for me to spend time with friends, because it aligns so well with my needs relating to being autistic.

This book explores the experiences of thirty-seven autistic people working in academia (thirty-eight if you include the author). As you read through the chapters, you will learn a lot about the experiences of these individuals as they navigate the university workplace, about the challenges they face and the value they bring to higher education and research.

In this chapter, I will tell you a little bit about these people beyond their work roles and employment experiences. In a different world I would introduce each of them to you by name and tell you about their unique personalities, interests, and gifts. However, we live in a world where autism is still very much stigmatised, and where disclosure comes with significant risks to career progression and social inclusion. Thus, many of my participants have asked to remain anonymous, and I will share their combined stories in a way that gives you a sense of their diversity while maintaining their anonymity.

Throughout the book, the participants are referred to by the pseudonyms of their choosing, and Table 1.1 outlines the age (at the commencement of the project) and gender identification of each individual. All other demographic information – such as country of residence, years in academia, or discipline – will be discussed in the context of the group to avoid the risk of individuals being identified by colleagues.

Table 1.1 Participants in the study

| Name | Gender | Age | Reflections |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alex | Non-binary | 34 | 4 |

| Amelia | Female | 23 | 12 |

| Amy | Female | 39 | 12 |

| Ava | Female | 50 | 3 |

| Baz | Male | 32 | 12 |

| Betty | Male | 32 | 12 |

| Charlotte | Female | 37 | 12 |

| Dave | Male | 46 | 12 |

| Dee | Non-binary | 47 | 12 |

| Ella | Female | 36 | 12 |

| Emma | Female | 30 | 12 |

| Eva | Female | n/s | 12 |

| Evelyn | Female | 28 | 10 |

| Flora | Female | 32 | 12 |

| Henry | Male | 39 | 6 |

| Isabella | Non-binary | 57 | 12 |

| Jade | Female | 27 | 11 |

| Jane | Female | 38 | 12 |

| Kelly | Non-binary | 51 | 12 |

| Liam | Male | 52 | 6 |

| Lisa | Female | 51 | 5 |

| Louise | Other | 42 | 12 |

| Marie | Female | 43 | 12 |

| Mia | Female | 57 | 12 |

| Moon Man | Male | 58 | 6 |

| Morgan | Female | 38 | 12 |

| Olivia | Female | 44 | 12 |

| Proline | Non-binary | 26 | 12 |

| Psyche | Female | 41 | 12 |

| Ruth | Female | 40 | 12 |

| Saskia | Female | 50 | 12 |

| Scarlett | Female | 37 | 12 |

| Scott | Male | 25 | 12 |

| Sophia | Female | 41 | 12 |

| Sunny | Other | 49 | 12 |

| Trevor | Male | 48 | 12 |

| Trina | Female | 42 | 12 |

Of the thirty-seven participants, at the time of the study thirteen were living and working in Australia, eleven in the United States, five in Canada, five in the United Kingdom, and three in Europe. The majority (thirty-two) had a formal autism diagnosis; two were undergoing a diagnostic process (and received a diagnosis prior to the completion of the study); and three self-identified as autistic.

Approximately one-third (twelve) had a doctoral qualification, thirteen did not, and twelve were currently studying for a doctorate. Their duration of employment in academia at the commencement of the study ranged from one year to twenty-three years, with a mean of 8.7 years (median eight years).

Contrary to the stereotype that autistic people cluster in information technology, the group were employed across a vast array of disciplines, with many in multi-disciplinary roles or concurrently holding roles in more than one discipline (see Table 1.2). The predominant discipline groups were social sciences (including psychology, sociology, social work, human geography, gender studies, child protection, and linguistics) and humanities (including philosophy, history, and German studies).

Table 1.2 Disciplines of participants

| Social science | 12 |

| Sociology | 2 |

| Psychology | 7 |

| Social work | 1 |

| Human geography | 1 |

| Gender studies | 1 |

| Linguistics | 1 |

| Child protection | 1 |

| Education | 10 |

| Primary/secondary education | 3 |

| Educational psychology | 1 |

| Higher education | 1 |

| Music education | 1 |

| Special education | 1 |

| English as a second language | 2 |

| Foreign language teaching | 1 |

| Health | 6 |

| Public health | 2 |

| Neuropsychology | 1 |

| Biostatistics | 1 |

| Speech pathology | 1 |

| Allied health (disability) | 1 |

| Physical sciences | 6 |

| Engineering | 1 |

| Environmental science | 1 |

| Physics | 1 |

| Environmental archaeologist | 1 |

| Urban sustainability | 1 |

| Systems science | 1 |

| Business and law | 5 |

| Leadership | 2 |

| Employment | 1 |

| Marketing | 1 |

| Law | 1 |

| Humanities | 4 |

| History | 1 |

| Philosophy | 2 |

| German studies | 1 |

| Arts | 4 |

| Artist | 1 |

| Creative writing | 1 |

| Film studies | 1 |

| Writing studies | 1 |

A significant number are in education (including primary, secondary, and higher education, as well as specialist areas such as educational psychology, music education, special education, and languages). Some are in the physical sciences (including engineering, physics, systems science, environmental science, environmental archaeology, and urban sustainability) and the health sciences (including public health, neuropsychology, biostatistics, speech pathology, and disability services). Others are in arts (including fine arts, film studies, and creative writing), and in business and law (including leadership, employment, and marketing). This is consistent with the (limited) data on autistic university students; for example, in a survey of 102 autistic university students in Australia and New Zealand, fewer than one-third were undertaking a STEM major (Anderson, Carter, and Stephenson Reference Anderson, Carter and Stephenson2020).

Of the thirty-one who engage in research, eight are specifically focused on research into autism and five on research that includes autistic people as well as other groups. The remaining eighteen undertake research with no, or minimal, direct involvement with issues related to autism (although that is not to say that they do not engage in autism research in their ‘spare’ time).

Home Life and Relationships

Approximately two-thirds of participants are living with their partner, with the majority of the remainder living alone. A minority live with parents, other family members, or a roommate, either for companionship or to receive or provide support. Some also live with their dependent children, and approximately half have pets in their home.

The participants ranged from very introverted individuals with few social connections to very extroverted with large friendship networks. Those who reported few if any social connections included some who find social interaction draining and need the isolation to recharge, some who prefer to spend their time with family, and some who would prefer more social interaction but find it challenging to make and maintain friendships, a situation exacerbated at the time by the COVID-19 lockdowns.

I know not all autistics are introverted, but I really do need my time to myself to recharge.

I am fairly introverted, so I am quite contented on my own. In other countries I’ve lived and worked in, I often do befriend co-workers and spend a lot of time with them outside work. Here in [country], that is not really a part of their culture. And, [country] has been on a strict lockdown since December, so I cannot really go out and spend time with people in person. Currently, I am by myself 95% of the time.

He [the narrator’s partner] is pretty much the only person I spend time with outside of work. I trust him and I do not have to play a role with him.… I also love my mom but unfortunately she lives really very far away. So I talk to her on the phone very often but I haven’t seen her in the last two years. And I miss her.

I always love seeing friends, but I often find that I seem to like their company more than they like mine, and I always still find myself sidelined for other, better friends.

Unfortunately, the biggest thing about the non-work me is my health and disability. I, like many autistic people, have Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome plus over a dozen chronic conditions that come along with it. Honestly, these days my health is the prominent facet of my life.… Unfortunately, a lot of autistic women have a similar circumstance.

However, the majority reported spending their time with their families and/or a small group of friends. This was not a function of the common and inaccurate stereotype of autistic people as isolated loners in their own worlds, with no desire for human contact. Rather, it was a combination of the quality and quantity of interpersonal interactions that we seek. Participants reflected on deep and meaningful connections with their partners, children, and close friends, and the enjoyment they experienced in spending time with people they felt comfortable and relaxed with. They also discussed the need to manage their energy levels due to the (social) exhaustion of work, education, and daily life in general, which will be discussed in detail in subsequent chapters.

I don’t really like socializing outside of work. I prefer to spend time with them [family] when I’m not at work.

I live with my partner and my kid, who like 99% of the time are the only people I spend time with outside work. I don’t really want or need much social contact and after spending almost all my energy on work, family and myself there’s really not much left over.

We have some friends we enjoy seeing, but for the most part we enjoy spending time just the two of us (mostly talking, watching documentaries, going on outings, traveling when we can).

We are not extremely social people, but we do have a small group of friends. We have one couple that we spend a bit of time with out of work (maybe one or two days/nights a week) and some other friends we see on occasion. We try to manage the amount of socialising that we do during the week and on weekends, so that we don’t end up exhausted.

A common thread in the reflection on friendships was the foundation in shared interests, with many individual friendships and friendship groups focused around a hobby or special interest. This is consistent with the findings of a recent review of the literature on autistic friendships, which concluded that autistic people, more so than non-autistic people, define friendship based on homophily and propinquity (Black, Kuzminski, et al. Reference Black, Kuzminski, Wang, Ang, Lee, Hafidzuddin and McGarry2024). Related to this was a view that strong connections do not necessarily require face-to-face contact but can be equally fulfilling if they are electronically mediated. Those with children in particular commented on the ‘safety’ of friendship groups consisting of other neurodivergent people.

I also lead a writing group, so the four other folks involved in that I spend a lot of time with – we meet every other week, but also enjoy writing together. I have an intermittent knitting group with another set of friends. And, well, just spending time with friends. I’ve always had a lot of amazing friends, and they’re really why I’m alive at all. Community is an enormous protective factor. My friends are all weirdos like me – I’m a pretty firm believer in just being authentic and letting the people who will mesh well with that in, even if it looks different from mainstream. I love them dearly.

My friends are a mixture of academics and people who are simply creative with a good sense of humor. I would say all of my longterm friends fit the creative personality even though not all of them are academically inclined. My shared hobbies with my friends include debating or discussing science or world issues, sharing digital art or playing online games, swimming and hiking, and spending time with my animals who are also some of my best friends.… I will still probably use text or email or the phone 90% of the time to talk to my friends but those in person lunches or swims 6 or 7 times a year mean a lot even for an extreme introvert like me.

I keep in touch with my close friends via text and sometimes phone or Zoom. Some people think that’s impersonal but most of them are Autistic and we have a really close bond.

I find the most safety with other parents of autistic kids, and other adults (parents or not) who are neurodivergent. They understand that some people behave in unexpected ways.

Hobbies and Interests

The group members’ hobbies and interests are as diverse as their academic disciplines and, again, demonstrate the inaccuracy of the myths around autistic people. By far the most common category of hobbies and interests was creative pursuits, ranging from painting to knitting to jewellery making and everything in between. Evident in participants’ descriptions were the many functions that engaging in these activities serve for autistic people, providing an outlet for stress, sensory input, repetitive movement (stimming), and providing a sense of safety and security.

I’m currently building a bed from scratch – wood and screws and a drill etc. I love having hobbies, I sew and crochet and scrapbook and design things, I am getting into basic interior design.… I want to learn to watercolour, make my own art and maps for DnD, I have a 3D pen I want to learn to use. I want to build my own furniture or at least upcycle it.

I really like making things and can’t remember ever not being like that – when very little, I wrote books, stories, poems, I drew detailed pencil drawings and I really liked origami. Crafts continued throughout adult life, and I got into modular origami, model making, I made greetings cards for a while, I made jewellery and chain maille, paper cutting, colouring, Lego building and collecting, and all manner of arts and crafts with my daughter too. I also learned a bit of coding, have kept up my spreadsheet passion, learned to design websites and do graphic art and design for various jobs I did, and I got pretty good at Photoshop.

Oooh so many! A love of beads and making jewellery is something I’ve done since I was about 10. Absolutely love it, love colours and collecting shiny things! I’ve been crocheting & knitting for about 15 years now – I feel safe if I take my project with me where ever I go. I suppose it’s the grown up equivalent of taking a teddy everywhere. Even if I don’t do it, I like to hold it.

I really enjoy woodwork and playing music but I don’t do that much of either these days. Both have been a passion since adolescence. I find the methodical nature of working with wood and doing something with my hands quite calming.

Contrary to the myth that autistic people lack creativity and imagination, in addition to these craft-related activities, many participants reflected on their enjoyment of writing fiction and poetry (including at least one famous novelist in our group). While early understandings of autism included the misnomer that autistic people have impoverished creativity (Craig and Baron-Cohen Reference Craig and Baron-Cohen1999), more recent research – alongside the increased recognition of autistic authors, actors, and artists – has demonstrated the fallacy of this viewpoint. In fact, recent studies have shown that autistic children do not lack creativity but have a unique creative cognition profile, including a greater capacity than non-autistic children to generate creative metaphors (Kasirer, Adi-Japha, and Mashal Reference Kasirer, Adi-Japha and Mashal2020), and that autistic college students enjoy fiction writing more than their non-autistic peers and write at a higher reading level with fewer grammatical and spelling errors (Shevchuk-Hill, Szczupakiewicz, et al. Reference Shevchuk-Hill, Szczupakiewicz, Kofner and Gillespie-Lynch2023).

I still regularly write poetry as an outlet and have a few folders of writing somewhere. I keep meaning to start writing creatively more often but at the moment I don’t write enough for my PhD so I can’t justify it.

Writing (Fiction, Poetry, etc.) – I have been interested in writing from the time I was 11 years old. I love to play with stories, explore ideas, and make discoveries as I write. I also like the way that many different subjects, memories, and ideas can build to form one story. It feels like a conversation with ideas.

I have so many hobbies and interests outside of work that it’s really difficult to find time to spend on them all! I love engaging in all of the arts, but particularly writing and visual art. I have drawn and painted since I was a very small child, and have written poetry, prose, short stories, stageplays, and screenplays. I use the arts to express myself, as I find it so difficult to express myself adequately through speech, and find it so difficult to be heard, seen and understood by others. By pouring my heart and soul into various art forms, it seems to be easier to communicate to others these parts of me that otherwise remain so invisible so frequently. In this way, I can ease some of the loneliness of being me. Music and dancing are more selfish … I indulge in these arts mainly for my own benefit. Both have been solo activities for me for most of my life, although I have had flurries of social elements in each over the years.

Other indoor activities that were commonly noted as hobbies and interests included reading, music, games (predominantly strategy games), and cooking. Again, participants articulated the function these hobbies served in their lives – including helping them to find an escape from their problems and place in the world where they could ‘fit in’.

I have always loved reading fiction since I was a toddler (I think was hyperlexic) – I ALWAYS have to have a book on the go otherwise I feel naked. It is also a wonderful escape for me, the best escape. I love fantasy & science fiction for that reason but I also love psychological thrillers and crime novels because I love the puzzle aspects of them.

At age 9, after discovering the concept of what-do-I-do-now books and the idea that one could design a system to run a simulated adventure – exploration, combat, conflict-resolution – I began what has become my greatest and most-rewarding passion – gaming. From designing my own game systems to play by myself, to having middle-schoolers ask to play in my games, to developing close friendships through my gaming, this passion has had a profound impact on my life and most of my social skills and understanding of humanity. A good game session is like a work of art, like a good book, but the group is involved in the telling, each member adding to the complexity and dynamics of the narrative. One could say that my later obsession with physics should have been an obvious career-choice – I love rule systems, and physics is the rule system of reality itself – much more complex and imaginative than anything a human could devise. To this day, I game twice a month, and much of my free time is spent crafting and designing the next game session. Check in with me in another 40 years, if I’m alive you’ll likely find me in a retirement home gaming with some old friends.

Participants also reflected on more active hobbies and interests, including bushwalking and hiking, exercise (from walking to highly competitive sports), gardening, and animal care. Some engage regularly in a variety of active hobbies, for example, Charlotte who regularly participates in both day and multi-day hiking, cycling, and stand-up paddle boarding. For others, it is more about being at peace in nature.

I think part of the reason I like walking in the countryside so much is because I’m looking at all the detail. I love the way the raindrops flash with sunlight on the trees, thousands of sparks of light, and I love the colour of the leaves when the sun shines through them, and I love the varied colours of the hills and fields. I think the walking motion is also soothing to both me and my husband. I love every change of colour in the sea and sky, and watching clouds and weather fronts moving in or past, and watching flight behaviour and wing shape and colour to distinguish the different birds, and looking at the changes in the sea that tell you where the fish will be massed, which in turn tells me where to look for dolphins and gannets. I love when there is no sound but the wind and the call of the occasional chough or oystercatcher or raven. That quietness is so important to me. Walking in the countryside is a special interest that I share with my husband; it’s as intense as the imaginary world games I played when I was a kid. Sharing a special interest is the most amazing feeling in the world.

I’ve been a martial artist since I was a teenager, although I haven’t always been actively training with a school.… During the pandemic the school offered classes over Zoom, which really helped me deal with the stress of both the pandemic and grad school.

Past hobby = cycling. I raced time trials on my new road bike in 2007, and started track cycling at the end of that year. I got my AusCycle coaching accreditation, and was assistant (female) coach of the Thursday evening cycling group for juniors and started training & racing myself.… I raced in a few Victorian Masters championships, and the Australian Masters Track Championships.

Our eclectic group of participants had an equally eclectic range of special interests beyond those discussed above – including photography, cyclones, dance, bees, food, Lego, medical procedures, perfume, languages, real estate, spirituality, and many other topics.

Two aspects of autistic interests that were commonly addressed in participant reflections were the distinction between ‘hobbies’ and ‘special interests’ and the potential overlap between interests and work. Special interests are intense, immersive, and often lifelong, bringing great joy and meaning to an autistic person’s life (and often referred to by others as ‘obsessions’). Hobbies, on the other hand, are activities that we dabble in that may be fleeting or engaged in at a superficial level.

Non-work me is 100% a photographer! When I photograph, I can get absolutely lost in it for hours. I forget to eat and drink and go to the bathroom. It becomes my world. My mind is quieter, and my focus is purely on what is in the little frame in front of me. It’s a beautiful experience of utter flow, and photography is one of the only places – actually, the only place – where I experience that feeling. I forget about the world and all the difficulties I face and the horrible aspects of much of reality and simply feel pure joy. It’s my meditation – my spiritual practice. I’m tearing up right now just thinking about how special it is to me!… [ whereas] Both of these (craft and cooking) are ‘hobbies’, not special interests, as differentiated by the very different level of passion!

I collect perfume. I’ve been doing it for 35 years. I am interested in all aspects of the process, from the molecular structure of the scents to their combinations to the marketing of them.

The autistic passion for reading and learning results for many in a synergistic relationship between ‘work’ (or study) and special interests, something that is reflected on in more detail in later chapters. Conversely, some reflected that their academic career had led them away from reading as a hobby, particularly those whose relaxation reading had always been non-fiction rather than fiction books.

Outside of work, I like hanging out with my dog, exploring interest areas (many of which are work related), and reading/listening to podcasts.

This question is a fun one. I would say a lot of my special interests revolve around academic stuff and I often spend time reading journal articles for fun. For instance although I am an education researcher I love reading articles on genetics and neurobiology for fun including genetic factors in autism and some of the studies on Covid19 genetics.

Outside of work, I am an extremely passionate autism researcher, currently working on my PhD. That’s my passion, my hobby, and my work to hopefully make some small improvement in how my people (autistic people) are treated in society.

I used to read, I used to read a lot but after I got into academia, I don’t do that anymore. Because I read so much as my job, the last thing I kind of wanna do is read. And that’s because the only books I read are non-fiction books, so it’s just … At the end of the day, you just don’t really wanna take in more information.

Would They Be Surprised?

When asked whether they thought there were things about their non-work identities that would surprise their colleagues, only three of the participants responded that they thought this would not be the case.

Many felt that their colleagues would be surprised by the nature, focus, or depth of their special interests. This was in a few cases the result of a deliberate decision not to share this information with others – for example, due to previous experiences of being belittled for having interests that were seen as childish or inappropriate – but in most cases due to a belief that others simply would not be interested. Others mentioned specific aspects of their life or experiences that they thought would surprise colleagues, either because of the preconceived ideas people have about ‘autistic lives’ or because of previous reactions from others to the revelation of personal facts (often that they themselves thought were unremarkable).

I don’t tend to talk a lot about my special interests at work and if I do it’s in fairly general terms so I think a lot of people would be surprised at how deep and broad my brain goes on them and how much time I spend focused on them.

I think they would be shocked at the range of previous jobs I have done and interests I’ve had. I do know other people that switch things around as often as me but I do find autistic people tend to know more about every interest they’ve had.

Things I think will surprise people they think are totally obvious (like my fountain pen collection) and things that I think are totally bland people will think are amazing (like when I went through a short phase of knitting fractals).

I think much of what I do outside of work would surprise my colleagues. There is an assumption that as a minoritized Autistic person, my life must be difficult and economic security must be difficult. Safety in general as a minoritized Autistic person is an issue but I am privileged to be living a good life.

A consistent theme in many of the reflections was that colleagues would be surprised to see them being their ‘autistic selves’ at home, that is, acting and being in ways that felt comfortable. These authentic selves are often very different to the neurotypical masks that autistic people are forced to wear in workplaces and other social settings in order to fit in and be accepted (discussed in subsequent chapters, and the consequences are explored in detail in Chapter 7).

I think most of non-work me would surprise my coworkers, including all the stimming I like to do at home.… Maybe the thing that would surprise them most is all the mental health stuff.

I think pretty much everything about the non-work me would surprise my colleagues. I am very different in my life at home. I dress totally differently on the weekend. I can stop playing a role and wearing a costume.

I function very well at work, but I think my work colleagues would be surprised at how low functioning I am outside of the work environment.

One thing that does relate a little more to work: I think people at work see me as an organized person. They might be surprised at the amount of work it takes for me to show up to meetings on time and remember regular tasks. They might also be surprised at just how much studying and reading I have done, to create the organizational systems that I use.

I think people would also be surprised how different my home life is to “normal people” – we’re a house of three autistic people who really aren’t interested in following the rules or the status quo. I get the feeling people would be surprised/horrified to see some of the ways our neurodivergent little household happily runs.

I can imagine that colleagues – e.g., my editor or academic supervisors with whom I’m not yet as close – may be surprised that I’m autistic. I feel like most people would be surprised that I’m autistic! There are some very pervasive stereotypes around autism that are ingrained in people’s minds, and they most certainly don’t look at a [physical description] who masks like a trooper and think to themselves, “that’s what autism looks like”. So much of my experience is very much an invisible disability – the struggles I face and the challenges I’ve had to overcome are internal and hidden in interpersonal interactions.

Other aspects of being autistic that participants felt would surprise their colleagues were co-occurring conditions and (the ongoing impact of) past experiences of trauma.

There are many parts of my life I keep private, mostly in relation to what I consider to be the abnormal or stigmatised aspects of my life that I have lived with forever. In the rare event I do disclose what my life is like or was like during my childhood I am always met with an odd amalgamation of shock and pity and sadness and praise for being so ‘resilient’.

They may also be surprised to hear that in all my life I have never felt safe, or known what it feels like to be accepted in the community. I seem to exist outside of my human body, and outside of the human race.

Some Final Thoughts

The aim of this book is to give you some insight into the experiences of these thirty-seven people. What they have in common is that they are autistic, and they are working in academia. This means that they share many of the same challenges and frustrations, as well as many of the same strengths and successes. However, what I hope this chapter has also shown is that this is a diverse group of people, and they are representing a wider cohort of autistic people working in academia who are equally diverse.

Stereotypes surrounding autism are pervasive and harmful. The stereotypes perpetuated by news and entertainment media typically portray autistic people as white males (Aspler, Harding, and Cascio Reference Aspler, Harding and Cascio2022; Jones, Gordon, and Mizzi Reference Jones, Gordon and Mizzi2023), or as children or adolescents, and assign us to roles such as a victim, a danger, a burden, or a savant (Gaeke-Franz Reference Gaeke-Franz2022; Jones Reference Jones2022b; Mittmann, Schrank, and Steiner-Hofbauer Reference Mittmann, Schrank and Steiner-Hofbauer2023; Yến-Khanh Reference Yến-Khanh2023). Such stereotypes, and the continuing use of the word ‘autistic’ as a pejorative (Patekar Reference Patekar2021), contribute to social exclusion and discrimination of autistic people (Hamilton Reference Hamilton2019; Fontes and Pino-Juste Reference Fontes and Pino-Juste2022).

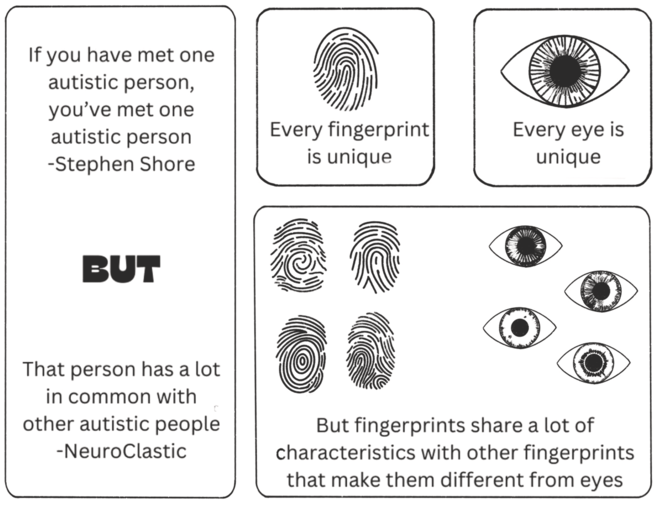

The reality is that autistic people – while sharing some key characteristics – are as diverse as non-autistic people. Throughout this book, I will often refer to strengths and challenges of ‘many autistic people’ or as ‘common among autistic people’, but beneath these generalisations are individual people who are each unique in their own constellation of autism and their identities and characteristics as individuals (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Autistic people are individuals.