Afterword

Summary

Slavery was an unavoidable and, some might have deemed, necessary adjunct of empire during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. All of the major European powers at one time or another entered the Atlantic slave trade, just as most of them possessed slave colonies. Yet it was the British who came to dominate the trade. Between 1662 and 1807, British imperial ships carried just over 3.4 million slaves from Africa, or roughly half of all the slaves shipped from Africa to the Americas in this period. Moreover, the slave trade was protected by powerful state interests, among them the Royal Navy, whose maritime ascendancy kept Britain's rivals – especially the French and Portuguese – at arm's length. Even after the abolition of the British slave trade in 1807, Britain remained an important slave power, with colonial possessions in the Caribbean that included Jamaica, Barbados, Nevis and St Kitts. Eventually, in 1833, slavery too was abolished but not without the British government having to make significant concessions. Not only were slaveholders in the Caribbean offered an apprenticeship system designed to ease the transition from slavery to freedom, they also received £20 million pounds in compensation, a huge sum that imposed a significant burden on the British taxpayer. Needless to say, the victims in this story – the 800,000 men, women and children who had survived the degradation and inhumanity of being enslaved – received nothing.

Not surprisingly, Britons chose not to dwell on this tangled history. Instead, they concentrated on a rather different narrative, one that stressed Britain's role in bringing slavery to an end. This culture of abolitionism was already in place by 1859, perhaps even earlier, and has proved remarkably enduring. To be sure, there were dissenting voices, among them Eric Williams, whose Capitalism and Slavery (1944) controversially dismissed the role of humanitarian reformers like William Wilberforce and instead argued that abolition was best understood in terms of the ‘decline’ of the British West Indies. ‘When British capitalism depended on the West Indies, [capitalists] ignored slavery or defended it,’ he boldly asserted. ‘When British capitalism found the West Indian monopoly a nuisance they destroyed West Indian slavery as the first step in the destruction of West Indian monopoly’.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

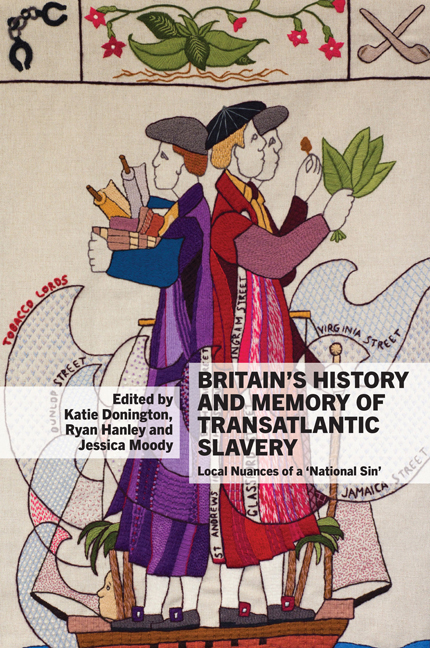

- Britain's History and Memory of Transatlantic SlaveryLocal Nuances of a 'National Sin', pp. 237 - 246Publisher: Liverpool University PressPrint publication year: 2016