Describing the atmosphere in Prague around Christmas Day 1914, the newspaper Národní politika remarked on the presence of a snowman at the top of Wenceslas Square. It commented on its surroundings: “Here and there, a carriage with a red cross drove by, a group of refugees weaved in with the striking figures of the Polish Jews, an invalid hobbled with difficulty – sights (zjevy) to which Prague is slowly getting accustomed.”Footnote 1 Cities located in the hinterland are sometimes perceived as sheltered from the reality of war. Prague represented this ideal of the home front as it was never, at any point during the war, in danger of being invaded or even close to combat. However, this did not mean that the city evaded the consequences of war, the pain of wounds, and the grief of death. In recent years, historians of the First World War have challenged this dichotomy between the protected, oblivious hinterland and the battlefront. Focusing on the links between soldiers and the civilian world illuminates the repercussions of war in the wider society. The urban setting provides an interesting lens to examine the back-and-forth movements between front and rear, as it became the center of many types of wartime mobility. The city also constituted one of the institutions that could mediate the war experience back to nonfighters (among others, from the family circle to the nation). The purpose is not to argue for the existence of a uniform Prague identity at war, but rather to draw attention to the concrete links of solidarity (and lack thereof) that the war highlighted.

This chapter shows how urban space in Prague was invaded by war and the suffering that attended it. First, by looking at the link between local identity and frontline soldiers, we will examine the connection with absent men and the transformation of mourning rituals through the celebration of the war dead. The presence of the war in Prague’s streetscape was also an absence, that of all the men who had left to fight on several fronts and sometimes died there. This “presence of absence” was tangible in the link the city maintained with its local regiments and the monuments built for deceased Prague soldiers.Footnote 2 The church bells being requisitioned for the war effort and the sudden silences in Prague’s soundscape also mirrored the absence of men.

The second focus is on the visible transformations the cityscape underwent with the arrival of war victims. Here, the city will reveal itself as a porous space that absorbed casualties from the front – the wounded soldiers and refugees who passed through or stopped in Prague during the conflict.

“Does Prague Still Exist?”: Collections for the “Prague Children”

The soldiers who had left civilian life to enroll in the army expressed sorrow not only at being separated from their families, but also at leaving their home town.Footnote 3 The men who had cried “Farewell Prague” from the train stations kept a mental image of the city’s streets with them. Nostalgia for the city itself found its expression in diaries, memoirs, and letters.Footnote 4 Serving on the Serbian front, Prague journalist Egon Erwin Kisch regularly expressed in his war diary the particular longing for the city as a whole, which came to symbolize all of civilian life. He described, for example, the mixture of jealousy and melancholy as two medical students received leave to take their exams: “Going to Prague! The warm longing (Sehnsucht), everyone’s thought.”Footnote 5 He also recounted the death of a fellow Prague man who called him by his side and said: “Greet Prague for me – I will not make it to Prague anymore.”Footnote 6 The newspaper Národní politika similarly stressed the soldiers’ homesickness: “it is even moving [to see] how Praguers, who often like to complain about this or that, remember abroad their ‘little mother’ and look forward to returning there! ‘Convey greetings to our little mother Prague’, soldiers write to us from the battlefront.”Footnote 7 The correspondence with relatives and acquaintances of prisoners of war in Russia also reveals reveries about the city and the wish to “be there” one more time. One wanted to be able “to walk again through Prague together as in 1911, 1912, 1913.” Another noted: “I often remember Prague. Before my eyes appear two-year-old memories.” Yet another closed his letter with “Cheers Prague! When do I come to you?”Footnote 8 Some of the men had, of course, more complex relations to their home city and not everyone was nostalgic, but the absence of many men who had been part of the city’s population was in any case not forgotten by the municipality.Footnote 9

Their Christmas collections maintained this symbolic link between soldiers far away and the city they came from. The gifts were provided through the generosity of the inhabitants themselves and displayed at the town hall on Old Town Square so that every resident could come to admire the solidarity of its fellow urban dwellers and remember the men who were fighting. The Local War Help Office, created in August 1914, organized the regular collections of gifts to be sent to the soldiers at the front.Footnote 10 Although the municipality in Prague was led by the Young Czech Party, the various charity actions undertaken by the Council were not systematically framed in national terms.Footnote 11 A call from October 1914 appealed to the “humane feeling of the whole population of the royal capital of Prague without distinction of class or nationality.”Footnote 12 Though mostly aimed at individuals, it also invited Prague firms to donate their products. The gifts (clothes, chocolate, cigarettes, tea, coffee, and others) or money had to be sent (or directly brought) to the town hall on Old Town Square. The donors were then invited to specify whether the gifts were intended for soldiers from the Prague regiments, for soldiers of the eighth army corps (half of Bohemia) or for soldiers in the field in general. The suburbs around Prague were urged to participate in these donations, but they were also coordinating their own relief efforts. Class played a role in the ability to participate. Even during the first months of the war, the inhabitants would not all have had the means to take part in such actions. The town of Bubeneč refused to organize a collection of Christmas gifts, explaining that the local population was not as rich as in Prague (inner city) and could not participate in another collection after the efforts of the previous weeks.Footnote 13 In Smíchov, the local council explained that they had organized their own collection.

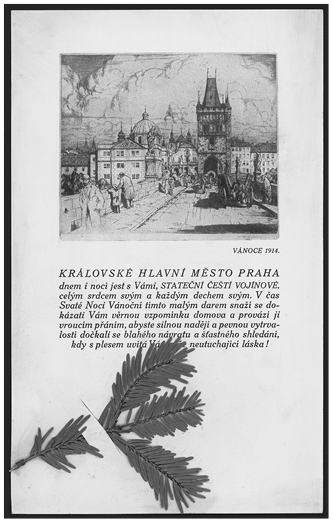

The parcels in 1914 not only contained small treats for the soldiers, but also a tangible piece of the city itself. Each soldier received a wooden tobacco pipe, zwieback, chocolate, and warm clothes, as well as a lithograph of the Charles Bridge and a little branch from the Christmas tree on Old Town Square (Figure 3.1).Footnote 14 The accompanying text (in Czech) read: “The royal main city of Prague is day and night with you, brave Czech soldiers, with all its heart and in every breath.”Footnote 15 In their reactions, the soldiers mostly accepted the synecdoche and expressed their gratitude to the city as a whole, not just the municipality. The overwhelming majority of the several hundreds of cards received were written in Czech, with a few written in German.Footnote 16 Many thanked directly the “little mother Prague.” “We children of the little mother Prague will never forget the blissful feelings that you ignited in us,” read one card, for example.Footnote 17 Other clichés such as “golden Prague” or “beautiful Prague” abounded. Soldiers signed, mentioning sometimes their regiment or unit, at other times their addresses in Prague or the neighborhood they came from. A soldier even mentioned his peacetime occupation. Czech identity was sometimes emphasized: “I cried at the thought that a Czech heart prepared it carefully for a Czech,” but more local identities could be on display: “The undersigned thanks for the Christmas gift that I received as a Prague citizen (příslušník)” or in another one: “we rejoice in the good fortune that you still remember your good citizens (občany).”Footnote 18 The letters often convey strong emotions (joy, tears) and the desire to be able to come back. An interesting testimony from a German-speaking Prague soldier, explaining how the war reinforced his sense of belonging to Prague, was published in the Prager Tagblatt: “The feeling of home (Heimatsgefühl) has become even stronger […] We are even better-disposed toward the Prague Council.”Footnote 19 The Council managed to send 5,000 parcels but, as it continued to receive more gifts after December, it organized a new dispatch in February 1915. For three days, all the gifts were exhibited in the town hall, a display which was to be repeated for the following distributions.Footnote 20 Such a display served as a proof to the inhabitants of Prague of their own generosity and participation in the war effort. It reinforced a sense of community, witnessing the quantity of gifts that symbolized the whole city’s participation.

Figure 3.1 Christmas card from the Prague City Council to soldiers with an illustration by T. F. Šimon, 1914

Even though the Council continued the practice, subsequent Christmas collections did not enjoy the same success.Footnote 21 A similar evolution could be observed in the case of Freiburg where the “orgy of public giving” during the first Christmas constituted an “early highpoint.”Footnote 22 In the following years, soldiers again wrote letters to the Council to ask to be included in the distributions: some because they had been missed out earlier and some because they had appreciated the previous gift and hoped it to be renewed. In these requests, the men underlined their connection (emotional or factual) to Prague. By 1917, as the economic situation on the home front deteriorated, the solidarity toward soldiers at the front could not be maintained at such a high level. Interestingly, a letter of thanks for the Christmas gifts included a reference to these conditions: “[The Prague children] were very happy that little mother Prague remembered them; they also remembered little mother Prague and its children having sent on January 1 money for hungry children to the center for Czech women. Gift for gift, love for love.”Footnote 23 At the end of 1917, the Christmas collection was renamed “for the benefit of soldiers in the field and the poor youth,” equating the suffering on the front and on the home front.Footnote 24 There was also no guarantee that packages would reach their destination in the disorganized war transportation system. Three boxes of gifts from Prague were, for example, robbed on their way to Békéscsaba (Hungary) in January 1917.Footnote 25 During the third year of war, Stanislav Neumann, who served in the twenty-eighth regiment, indicates that they only received the Christmas liebesgaben (gifts) in March 1917 and that these did not come from “home” but from Hungary, with calendars in Hungarian.Footnote 26

The Municipal Council also collected Czech-speaking newspapers and books on busy street corners to be sent to wounded soldiers all over the monarchy. As a brochure from the Local War Help Office explained: “every pedestrian around Prague is nowadays familiar with the collecting boxes dispatched in frequented places (voting urns whose former purpose was substituted in wartime) with their famous red inscription: newspapers for wounded soldiers….”Footnote 27 This initiative, unlike the gift collections, was not aimed at men from the Prague regiments but at Czech-speaking men in general. It reveals the ambition of the Council to lead welfare actions at the level of the Czech nation and take care of Czech-speakers. Individuals took part and donated reading material, but also several publishers. By 1916, the Council had already sent 80,000 volumes of books and newspapers to 1,388 hospitals.Footnote 28 Despite its success, demonstrated in the many letters of thanks received by the Council, this initiative was also showing signs of dysfunction in 1918. Soldiers, for example, noticed that half the contents of the package had been stolen before it arrived.Footnote 29

The metaphorical link between the city and its soldiers was particularly embodied in the relationship to the twenty-eighth infantry regiment. It was the local regiment and its soldiers were nicknamed “Prague children.” The veteran association of the regiment bore the official title of “Pražské děti.” Before the First World War, 95 percent of the regiment were Czech-speakers and most of the men were from Prague.Footnote 30 The war gave renewed meaning to the attachment between city and regiment, in both official and more spontaneous ways. The mayor celebrated the local servicemen’s accomplishments in municipal meetings.Footnote 31 Newspapers ran articles written by soldiers from the twenty-eighth regiment recounting their lives at the frontline and participation in combat.Footnote 32 The café “Corso” on the Graben/na Příkopě, largely frequented by a German-speaking clientele, collected money among its regulars to send tobacco to the twenty-eighth regiment for the first war Christmas, an initiative which is evidence that the connection was not only institutional and could transcend national allegiances.Footnote 33 Soldiers naturally turned to the city for specific requests, such as musical instruments to be sent to the front.Footnote 34

This regiment became, of course, famously known during the war for the alleged desertion of some of its soldiers in April 1915. As a result, the entire regiment was disbanded by the Emperor. Historian Richard Lein has now definitely demonstrated that the high losses during the battle on the Eastern front were not caused by an en masse surrender and that the Austrian military had overreacted in dissolving the regiment, as it was too happy to shift the blame of defeat onto Czech units.Footnote 35 Despite its popularity in Prague, the regiment’s alleged desertion was used in the hinterland as a way to disparage Czech soldiers in general and Czech participation in the war. Fake orders from the Emperor or imperial officials with an invented text were copied and circulated in the monarchy and especially in Bohemia. The war ministry decided not to pursue the propagators of such rumors.Footnote 36 A fake order from Archduke Josef Ferdinand casting “dishonor, shame, contempt and opprobrium” on the traitors and calling for a bullet or a hanging rope for them was, for example, sent to the Prague Mayor in August 1915, showing again the link made among the public between the city and its regiment.Footnote 37 Municipal authorities distanced themselves from this act of treason and mayors from the Prague suburbs came to proclaim their loyalty to the governor.Footnote 38 The Mayor of Prague sent a manifesto to the Prime Minister condemning the desertion and expressing his regret that some of the men were from Prague, when the city had “so many times” demonstrated its devotion to the dynasty.Footnote 39 Some Czech politicians, however, refused to sign a condemnation of the regiment, doubting the official version of events. Jan Herben explained that the officers campaigning for reinstatement expected that “Prague would stand by the Prague children” and that a statement would look bad in that context.Footnote 40 As it was reinstated in January 1916, after one remaining reserve battalion had fought with exemplary bravery on the Italian front, the city authorities received several telegrams from officers and men informing them of the regiment’s celebration at the news.Footnote 41 The mayor wrote to congratulate them, praising the soldiers’ courage.Footnote 42 The constant support of the city’s elites was appreciated by the officers:

Throughout the whole war, the Prague Council has shown our regiment the greatest courtesy. The real motherly care of the men in the k.u.k. 28th regiment secures our greatest gratitude to the royal capital of Prague. For the reinstatement of our regiment, the royal capital of Prague was among the first who rejoiced in this meaningful moment. […] all these proofs of sympathy can only raise the spirit of the men in the fulfilling of their difficult duty, which they readily accomplish with great love for our supreme warlord, the dear fatherland, and for the honour of the royal capital of Prague.Footnote 43

In the following months, the city continued to pay homage to the twenty-eighth regiment by sending a hero album and a silver horn in February 1917.Footnote 44 The patronage of the regiment by the city authorities reveals the Czech elite’s reaction to accusations of Czech disloyalty: they still proclaimed “their” soldiers’ bravery. Defenses of the regiment’s record were also found among other classes. A waitress in a night café, for example, rebuffed a reserve officer who had insulted the men from the twenty-eighth regiment while himself not fighting at the battlefront.Footnote 45

The city, both as a symbol and as an institution, acted as a mediating factor between civilians at home and “their” absent soldiers in the field. The gifts sent to them offered by the inhabitants themselves maintained a link with all those missing in every neighborhood or street. Displayed in the Town Hall, the gifts evoked all the men to whom they were destined. The little branch from the Christmas tree on Old Town Square assumed a shared Prague identity, an emotional attachment to the place they came from, and common prewar urban experiences. Urban identity was called upon to stimulate solidarity. This solidarity was not exclusive; it could be inserted into broader national or imperial frameworks of allegiances. The particular relationship to the twenty-eighth regiment was nurtured during the war, despite the disbandment. The city and its elite stood by their own soldiers. They condemned the treason, but only while praising the courage of the troops otherwise. The concept of solidarity between the battlefront and the home front became the guiding principle of the relief actions. As the war progressed, however, these boundaries became blurred: the home front itself was suffering and could not offer the same reassuring protection.

Mourning in Absence: Soldiers’ Graves and Church Bells

Remembering the city’s soldiers also meant paying homage to the war dead. By the end of 1917, 3,064 men from the inner city had died in combat, 9,902 including the nearby districts.Footnote 46 The largest Prague cemetery of Olšany, on the East side of the city at the border of Král. Vinohrady and Žižkov, hosts to this day a monument to the soldiers fallen during the First World War. It consists of individual plaques affixed to one of the walls, which mix legionaries who fought on the side of the Entente and those who died in the Austro–Hungarian army. The general emphasis is on the legionaries’ experience with the central monument dedicated to them. Most of the monuments commemorating the First World War in Prague were built after the war and would reflect the ambiguity of celebrating men who fought wearing the Austro–Hungarian uniform in the new Czechoslovak republic.Footnote 47 Part of the memorial in the Olšany cemetery, however, was erected in 1917.

The small plates indicating the name, unit, rank, dates and places of birth, and death of fallen soldiers represented men from Prague whose bodies could not be repatriated. This celebration of fallen soldiers without graves or bodies is typical for the many soldiers of the First World War who were mourned far away from their burial place. Families in most belligerent countries were not able to retrieve the soldier’s remains to perform a wake or a funeral. The absence of a body to mourn and the inability to have a proper burial often aggravated personal grief.Footnote 48 The initiative in Prague underlined this aspect of the absence of the deceased: its name was “Hrob v dáli” (grave far-away) and it was presented as a way to link grieving families in Prague to their loved ones who had been killed at the front. Military commander Zanantoni recalls the initiative in his memoirs and the active role played by one of his subordinates, a Czech captain who had lost his son in Serbia without being able to recover the body and devoted all of his free time to the graves.Footnote 49 At the time of the unveiling of the “grave far-away” plaques, only 170 names were featured on the wall (nowadays there are about a thousand).Footnote 50 The nearby monument built by the city, partially with the help of donations, showed two mourning female figures crying over the soldiers’ deaths.Footnote 51 The inscription (now erased) read: “Prague to the heroes, 1914–1917” with a representation of the city’s emblem (three towers) (Figure 3.2).Footnote 52

Figure 3.2 Monument in Olšany cemetery, 1917

The unveiling of the monument of the “grave far-away” on June 29, 1917 coincided with the traditional “May celebration” (májová slavnost/Maifest).Footnote 53 The homage paid to dead soldiers was paired with this very local ritual. This Prague festival, held in local cemeteries, was created in the early nineteenth century – at the height of Romanticism – to celebrate resurrection, linking homage to the dead and to nature in spring. Flowers were an important feature of this holiday. The memorial was inaugurated in the presence of local and military authorities, the city corps, and chaplains of diverse faiths. The attendance was “enormous” according to the newspapers. Two grenadiers were standing guard near the monument, while the Czech national anthem Kde domov můj? was accompanied by sobbing widows and orphans. The procession laid flowers at the “grave far-away” memorial and then attended a military mass near the honorary graves.Footnote 54 For the following All Souls’ Day, a composer from the Prague music academy dedicated a hymn entitled “grave far-away” to be used in all church memorial services “to remember the members of our fatherland (vlast) who rest in foreign lands, far from their homeland (domovina).”Footnote 55 During the ceremony, which was “more mournful than the year before,” a local choir sang the new hymn.Footnote 56

The First World War implied everywhere a “militarization of the cemetery,” whereby traditional mourning sites became the focus of collective and public mourning.Footnote 57 The military section of the cemetery hosted honorary graves where soldiers who died in hospitals in Prague were buried.Footnote 58 By June 1917, 1,700 men and officers were buried there and another 627 in private graves. On average, three soldiers a day were inhumed in the Olšany cemetery at that time.Footnote 59 Officers sometimes had the privilege of a procession through the city.Footnote 60 The growing number of soldiers dying in Prague required an expansion of the existing cemeteries. The municipality bought a new plot in 1917 to enlarge Olšany cemetery and a new military section was created in the Strašnice municipal cemetery.Footnote 61 The traditional celebrations of the dead in the spring and the autumn took on a new meaning with the war casualties. Cemeteries became even more frequented than in peacetime. During the May celebration of 1915, the number of tramways leading to the cemetery was increased to accommodate the population attending.Footnote 62 In 1916 and 1917, the celebrations in Olšany were also well attended. All Saints’ Day in 1916 was marked by the interdiction to light the customary candles on the tombs and to replace them with an offering for soldiers’ widows and orphans. A priest in Žižkov noted that the public did not take it well and that some secretly lighted a candle in their homes.Footnote 63 This measure subverted traditional mourning rituals and converted the celebration of private loss into a public commemoration of the war dead.

The association “Black Cross” was one of the primary fosterers of this community of mourning. It organized various ceremonies in cemeteries throughout the Empire. The aim of the local branch founded in 1915 was twofold: taking care of soldiers’ graves in Prague (and later Bohemia) and helping family members to locate the graves of their loved ones in other regions or abroad. The action was intended for everyone “without distinction of nationality or religion.”Footnote 64 This syncretism appeared, for example, at the 1915 Christmas ceremony, where various regiments sang Czech, German, Hungarian, and Polish carols as well as the imperial anthem.Footnote 65 The committee visited Jewish war graves as well as Christian ones on their inspection of the cemetery in January 1917.Footnote 66 Financially, the “Black Cross” relied on contributions from its members but also heavily on the help of the Prague Municipal Council. During the “May celebrations” of 1916, families from Moravia, Hungary, or Croatia who had a member buried in Prague were invited to participate and the Council provided them with food and accommodation.Footnote 67 In 1918, the association asked the Council to create a subscription for local families to be able to visit the grave of their son, husband, or father.Footnote 68

Monuments to fallen soldiers in other public spaces were planned during the war. An exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in July 1916 presented these projects. The contest, open to all artists from Bohemia regardless of nationality, drew over 300 entries.Footnote 69 A monument to the twenty-eighth regiment and its battles on the Italian front, entitled “To our heroes, 1916,” was, for example, envisioned in the Rieger gardens in Král. Vinohrady. Many proposals were stylistically inspired by the recently unveiled monuments to the historian František Palacký (Slanislav Suchard, 1912) and to the Protestant reformer Jan Hus on Old Town Square (Ladislav Šaloun, 1915).Footnote 70 Šaloun himself was supposed to design a monument to fallen soldiers in the Saint-Nicholas Church on Old Town Square.Footnote 71 This baroque church stood as a symbol of the wartime militarization of religious buildings and rituals. Used as a Russian Orthodox church before the war, it was repurposed in 1916 as a Catholic garrison church.Footnote 72 As the governor explained, the “architectonically remarkable” building on a “historically memorable” square was perfectly suited for a garrison church. The Catholic services “in a great beautiful church, often accompanied by military pomp” were to act as a counterweight to the nearby memorial to reformer Jan Hus.Footnote 73

Monuments and celebrations aimed at giving an imprint of the absent men in the urban landscape. The churches themselves became a vivid reminder of the sacrifices required from the population in wartime.Footnote 74 In 1916 and 1917, most of the bell towers in Prague saw at least one of their bells being taken down and requisitioned for the production of ammunition. The most historically significant ones were preserved but still about half of the Prague bells were melted down. Bells were not for parishioners a mere inanimate object, but a member of their community. They had a name and their departure was felt as an additional separation required by wartime. The silent churches recalled the absence of men.Footnote 75 The parallel between the requisition of bells and the mobilization of soldiers is a recurring motif in contemporary accounts. A parish newsletter mentioned that the death knell in the village of Ořech near Prague was “the first who had to march (rukovat) to war.”Footnote 76 This comparison echoed a patriotic language of sacrifice and, in so doing, softened the blow of the requisition. In a time when men were giving their lives for their country, the sacrifice of bells could be presented as a relatively less painful one. The strong attachment of parishioners to their bells and their immediate tie to a feeling of home set them apart from other requisitioned objects.

As soldiers took the bells away and loaded them onto carts, the parishioners or simply curious crowds often gathered to wish them a last farewell. Tears form a recurring part in the description of the bells’ departure found in various sources: parish chronicles, parish newsletters, as well as newspapers’ reports. In Nebušice near Prague, “the removal of these bells caused many painful tears, especially for older parishioners.”Footnote 77 The priest in Bohnice, another hamlet of Prague’s periphery, described “a big crowd of adults and children […] almost all with tears in their eyes.”Footnote 78 The parishioners’ tears visibly expressed the sense of loss provoked by the bells’ seizure. The tears become such a figure of speech in describing the requisitions, that they are sometimes mentioned even years after the fact. On the occasion of the consecration of new bells for the Týn cathedral in Prague, a newspaper article recalls the requisitions as “begging a tear from more than one of the Týn parishioners.”Footnote 79 The presence of tears, often as teary eyes rather than full weeping, embodies the emotional bond with bells. These public tears, shared with others and visible to all – when crying was still an intimate and private matter – reinforced the currency of the community through loss.

The last goodbye evoked past losses and funerary practices. The description of the church tower after the removal in a parish newsletter underlined this connection with death and the passing of a loved one: “How empty and sad it was in the tower, just as when they carry from the house a deceased who is not coming back.”Footnote 80 In the context of the war where potential or actual death was omnipresent in the lives of families, funeral practices such as black ribbons or flower wreaths placed on the bells linked once again the requisitions to the soldiers fighting.

The attachment to bells in larger cities was different from that of rural inhabitants in the countryside where the village bell fulfilled many functions as markers of time, alarm in cases of emergency, as well as symbol of the community.Footnote 81 However, in a city such as Prague, it was the choir of all the church bells that played an important role in urban identity. By the early twentieth century, bells did not constitute such a prominent feature of the urban sound environment anymore as they were in competition with other noises. This did not mean that they had lost all meaning; they remained an important part of urban soundscapes, especially in the provincial capitals compared with the new metropolises. The ringing of all bells together was a very choreographed and hierarchical event in the prewar. The last time it took place in Prague on the eve of Saint Wenceslas Day in September 1916 illustrated the new aural void caused by the war. Newspapers mentioned to their readers that the requisition meant that this was the last opportunity to hear a “peal of such magnitude.”Footnote 82 City dwellers were invited to trek to the various public gardens on the hills surrounding the city to hear the last concert of bells that lasted half an hour. The priest of Saint Stephen mournfully mentioned this last festive ringing in his chronicle: “They rang above us for the last time.”Footnote 83 Newspaper Prager Tagblatt lamented the swan song of bells and emphasized their centrality as markers of urban identity: “Bells belong to the city and it is as if a part of the city was sacrificed.”Footnote 84 The variety of sounds that filled the air in the rare occasions where they all rang was a source of urban pride. Národní politika mourned the “poetic sea of sweet sounds, which Prague was renowned for.”Footnote 85 In a lecture to Catholic women, a priest described the particular enjoyment of listening to the peal of all the churches: “We are all witness to it: […] how lovely it was then, especially on Petřín hill, to hear their choir.”Footnote 86 It was a custom of the prewar period for enthusiasts to climb to Petřín on the eve of holidays to “revel in the sacred music.”Footnote 87 The loss of the bells symbolized the transformations of the relationship to death in wartime Austria–Hungary, making loss an integral part of the aural landscape

The Loss of Saint Ludmila’s Bells

The neo-Gothic church of Saint Ludmila on Purkyně Square also had to relinquish its bells for the war effort (Figure 3.3). The church had been built only a few decades prior and none of its bells were historically significant. As soldiers took away the largest bell “Václav,” the pavement in front the church attracted a small crowd of curious onlookers who came to say goodbye. “The grandmas who are zealous visitors of the Saint Ludmila cathedral touched the bronze metal with their hands and blessed the bell with a sign of the cross – on its final journey.”Footnote 88

Figure 3.3 The requisition of the largest bell of the church of Saint Ludmila, November 6, 1916

In cemeteries and churches, Prague residents reckoned with the absence created by war, often synonymous with death. The homage paid to fallen soldiers accommodated different conceptions of the homeland. Collective mourning attempted to offer common rituals, linking them with local traditions, in the absence of bodies to bury. The disruption of funeral practices was reflected in the departure of church bells, which had been an important part of the aural landscape of the city. The absence of bells from church towers reminded Prague residents of the sacrifices of war. As mourning created communities that grieved for their losses, the new presence of strangers in Prague implied a different engagement with war casualties and a redefinition of community boundaries.

Battle Scars: The Presence of Wounded Soldiers

From early September 1914, the evacuation of both wounded soldiers and civilians to the hinterland generated a continuous flow of arrivals into the city. These thousands of newcomers appeared as a novelty in the cityscape. Their aspect revealed the physical and psychological effects of war. Buildings needed to be converted for their accommodation. Municipal authorities attempted to welcome them as victims of the conflict, while at the same time shielding Prague’s inhabitants from the impact of war. The spread of epidemics became a major concern, which links the First World War both to previous conflicts in the nineteenth century (such as the war of 1866 when cholera broke out in Prague) but also to prewar hygiene considerations.Footnote 89

The influx of wounded and sick soldiers into the city transformed the use of public space. Many major buildings were turned into hospitals and convalescence homes. Train stations were filled with transports of wounded men who were daily reminders of the realities of war in the field. City dwellers were thus confronted with the immediate impact of the conflict and the way the state was taking care of its soldiers. Convalescents, or those who were able to, would take walks through Prague as pastime. Austrian historian Viktor Thiel remembered his leisurely walks around Prague, happy as he was to escape his cramped and dirty hospital room.Footnote 90 As Národní listy noted, the wounded came from all over the monarchy. “To all of them, the public significantly devotes their attention and it is a very common occurrence for the soldiers to be offered tobacco.”Footnote 91 Wounded soldiers also regularly visited theaters and cinemas. Every week from 1916 to 1918, one of the city’s main theaters (one German and three Czech, including the National Theatre) put on a special show, usually an opera or operetta to avoid language difficulties, reserved for the wounded.Footnote 92

Bohemia, situated at the rear of any front line throughout the war, was a prime destination for wounded soldiers. The overall capacity in Bohemia for military and Red Cross hospitals reached 65,000 in the autumn of 1915.Footnote 93 The crownland housed between 16 percent and 33 percent of the beds in Red Cross hospitals in Cisleithania (depending on the stage of the conflict). It had the highest number of hospitals for most of the war (only overtaken by Lower Austria in 1916). This fact is hardly surprising given the number of hospitals in Bohemia in the prewar period, but it highlights the crownland’s role in the war effort. The number of beds grew during the first two years of the war to slowly decline in 1916, 1917, and 1918.Footnote 94 In Prague, where there were sixty-five war hospitals, the number of soldiers arriving in the city followed the same pattern. While over a thousand wounded soldiers were arriving every day in 1915, by 1917 and 1918, the new arrivals at the train stations were mostly convalescents, and often numbering no more than a few hundred.Footnote 95 In 1915, there were 22,300 hospital beds for soldiers in Prague and overall, 258,835 wounded and sick soldiers were housed in Prague hospitals over the course of the war.Footnote 96

The first major transport of wounded soldiers arrived at the Franz Joseph train station on August 30, 1914.Footnote 97 Crowds went to the train station to witness their arrival in these first few weeks, partially out of curiosity but also to get news of the front or potentially of their relatives. Národní politika describes such a scene of welcoming in September 1914:

The wounded soldiers arrive! […] it goes from mouth to mouth and already one runs to the railway to be able to greet from close the brave soldiers coming back from combat and look at these men whose deeds and sufferings one read about in the newspapers. Slowly the first tramway with a red cross on the lamp moves on Wenceslas Square away from the Museum. In a few moments it is surrounded from all sides by a crowd waving handkerchiefs and shouting ‘Na Zdar!’. It sounds heartfelt and sincere but a bit muffled. […] everyone remembers that these are wounded people, who at that moment suffer physical pain. Still one wants to welcome them and somehow manifest one’s sympathy.Footnote 98

The article also depicts the chalk inscriptions on the trains in Czech, German, Hungarian, or Polish. “Here are the Prague children…” read one of them.

The police took measures to keep the crowds out of the stations. The Prague railroad commander complained that too many people were present and hindering the process.Footnote 99 One needed a “legitimation” card from the police or the City Council to help with the transports.Footnote 100 The authorized personnel consisted of medical military men who moved the soldiers, policemen who regulated the traffic, and Red Cross women wearing an armband. Red Cross volunteers provided refreshments to the wounded soldiers (soup or sandwiches, beverages like tea or coffee, but also cigarettes). Alcohol was strictly forbidden.Footnote 101 The main train stations of arrival were the Franz Joseph station, the State train station, and the North-West train station. Some wounded transports also arrived at the Bubny station (until 1915) in the north of the city. Men who were to continue their journey needed to have accommodation space in the railway buildings. The treatment of the wounded revealed the expected physical division between officers and men and the railway authorities requested to have them accommodated separately at the State train station.Footnote 102 The Prague Voluntary Safety Corps (first aid service) coordinated the use of automobiles for ambulances (borrowing vehicles from the local firemen as well as from individuals and firms).Footnote 103 Special tramways were chartered for the transport of wounded soldiers within the city (eighteen of them in 1915) and new tracks led them directly from the main train station to the garrison hospital. Besides, wounded soldiers were entitled to free transportation.Footnote 104

Prague’s welcoming atmosphere for wounded soldiers was, however, not to be sustained throughout the war. In 1916, a physician remarked on the change of attitude in the public: “Everyone certainly remembers the huge crowds of people hustling to see the transports of wounded soldiers. Today barely anyone notices it.”Footnote 105 The curiosity and novelty had worn off, and as the war went on, a form of indifference replaced it. Public empathy with the wounded could even turn against the military authorities in view of the treatment the soldiers received. A policeman reported frequent complaints from local inhabitants near the Pohořelec barracks who saw wounded soldiers waiting on the square in tramway cars for someone to take them inside. They could lie there for a long time in bad weather or at night, and people from the neighborhood would sometimes step in to help them to walk into the hospital. “Such scenes […] provoked among the present public bitter feelings of indignation,” indicated this policeman.Footnote 106 He insisted in his report on the recurrence of the phenomenon and his statement was undersigned by several other police officers. This case shows how, despite efforts to shield civilians, wounded soldiers were an insistent presence in Prague’s urban space. They were daily reminders of the damage caused by the war. Moreover, as the number of wounded transports coming into the hinterland grew, Prague residents witnessed first-hand the increasing strain on the state and the inadequate care it provided for its citizens.

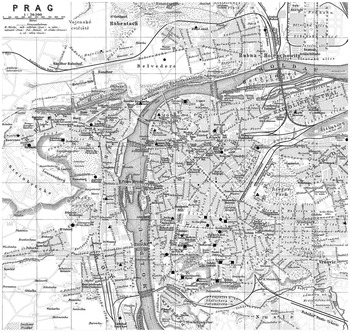

The growing contingents of wounded soldiers required buildings to house them. Prague possessed a garrison hospital on Charles Square and its affiliates in Albrecht barracks and on Hradčany.Footnote 107 Different types of medical institutions undertook the care of the wounded: hospitals, military hospitals, Red Cross reserve hospitals, military and Red Cross affiliate hospitals, other medical institutions and private care facilities (see Map 3.1).Footnote 108 The Ferdinand army barracks in Karlín were the largest reserve hospital in the city with 1,600 to 2,000 beds. Civilian buildings were requisitioned to be transformed into hospitals. Hospitals and sanatoriums were, of course, supposed to clear some of their beds for military purposes. Larger school buildings were also extensively used.Footnote 109 The Straka Academy, for example, an institution for poor noble students on the banks of the Vltava, provided 475 beds for wounded soldiers. The changes inside buildings introduced by this new function were not always welcomed by the institutions owning them. The Straka Academy was trying to preserve some room for its students and did not want the whole garden to be transformed into a vegetable plot for the hospital.Footnote 110 Other schools complained of dirtiness and pupils’ teaching being relegated to the corridors.Footnote 111 The Institute for the education of female teachers lamented the loss of the parquet floors in the gymnasium.Footnote 112

Map 3.1 Buildings hosting wounded or convalescing soldiers (■: medical/charitable institutions, ★: military buildings, ●: national associations, ◆: train stations, ▲: schools and universities, •: religious institutions, ●: private houses)

In some parts of the city center, the care of wounded soldiers took over an important number of buildings. The priest of Saint Stephen Church in the New Town recorded in his chronicle all the buildings in the immediate vicinity of his parish that hosted wounded men: the military hospital and the Czech Engineering School, both on Charles Square as well as the Red Cross Hospital in nearby Ječná Street. In that same street, a nuns’ monastery also hosted seventy beds. In the perpendicular street, the house of the German evangelical deacon and the Sokol practice hall had been turned into makeshift hospitals.Footnote 113 Religious institutions (Catholic, evangelical, and Jewish) and national institutions offered their own buildings for the housing of wounded soldiers. As we have seen, the Czech Sokol lent many of their practice halls in the city and suburbs. The German house also lent part of its building. The German student home ran a convalescence station for German students. The suburbs had less concentration of buildings devoted to the wounded but nonetheless, Žižkov, for example, had three hospitals for the wounded: in the Sokol training hall and in two schools.Footnote 114 Finally, convalescing soldiers were sometimes accommodated in private houses or villas of citizens who accepted to take care of them (in many cases, they requested to be sent officers rather than regular men).Footnote 115

Sokol Nurses

The Sokols organized nursing classes in the National House on Purkyně Square. Forty-four women participated in the first month-long course in August 1914 and thirty-three in the second one in October. They then went to work as nurses in the various hospitals in the city. After a year and a half of voluntary service, helping soldiers and assisting doctors, the Sokol nurses asked the Red Cross for financial support. As they explained, they did not come from affluent backgrounds and could not support themselves while continuing the very intensive work of nursing when shifts could go for two days through the night.Footnote 116

The local public who helped with the care of the wounded had access to a new range of buildings and institutions that had been previously closed to them (monasteries, palaces, schools): the new purpose of the buildings hence also transformed the lived experience in the city. A Sokol who found himself, as a wounded soldier, in a practice hall he knew from before the war described the painful contrast between his memories and the present use of the building: “It is here full of movement, but this movement is not the healthy and joyous movement of training which filled our hall with beautiful sights.”Footnote 117 In their new guise, the buildings still kept traces of the prewar use. The picture below drawn by a Polish-speaking wounded soldier highlights the opposition between the light peacetime wall decorations in the Sokol building and the current dark beds of the wounded (Figure 3.4).Footnote 118

Figure 3.4 “The ‘Prague Sokol’ in 1914”

The integration of wounded soldiers into many formerly civilian buildings favored contacts with the local civilian population. The rare men who were staying in private houses were not the only ones who came into contact with Prague inhabitants. From their arrival at the train stations, wounded soldiers came in contact with volunteers. Sokol men, for example, helped carry the wounded on a voluntary basis day and night.Footnote 119 Women brought various gifts to soldiers in the hospitals: food, cigarettes, warm clothes, or reading material. Students from the Institute for the education of female teachers were, for example, making slippers and baking for “their” soldiers (meaning those housed in their building).Footnote 120 The Prague City Council organized a collection of fruit, especially in nearby estates, and middle-class women cooked preserves to be distributed in the different Prague hospitals in December 1916.Footnote 121 The League of Germans in Bohemia opened a reading room for convalescing soldiers, while the Café Continental created a resting home on its premises in 1915.Footnote 122 Another reading room near the Jindřich Tower in the business quarter provided 500 men per day newspapers, books, and even coffee, in a bright space with large windows welcoming every nationality.Footnote 123 The men would also visit civilians in their homes. Marie Schäferová recalls how her mother was welcoming soldiers into her house, especially those from her hometown, but also a man from Bosnia:

The wounded were lying in hospitals on top of each other, there was little room, awful things were told about unimaginable suffering and horrible injuries, cigarettes, food, bandages were collected, whole rows of voluntary workers took over service in hospitals and the wounded, when they were allowed to go out, would find refuge with acquaintances who tried to alleviate their suffering. To our house came men from Černovice, whom we previously were bringing food and cigarettes to […]. And with them came one day a soldier from Bosnia […] who got used to coming to our place like to his home.Footnote 124

Thus, wounded soldiers brought war with them into the hinterland, through their stories and their own sufferings. The Bohemian authorities worried about the potential for alarming reports of the battlefield situation, circulated by sick and wounded men, to feed antimilitarism.Footnote 125 This fear of their role in spreading rumors was combined with a concern for deserters and shirkers in hospitals. Two cases of soldiers deserting while convalescing were reported in police files.Footnote 126 In hospitals, men would sometimes fake illness to not have to return to the front. Czech shirkers in hinterland hospitals feature prominently in Hašek’s description of the war in The Good Soldier Švejk. Beyond the satire, the reality of soldiers malingering in Austro–Hungarian hospitals might have been more complex.Footnote 127 A Prague doctor’s postwar testimony highlights the blurry limits between psychologically traumatized soldiers and shirkers. In the context of manpower shortage, army physicians tended to diagnose truly ill individuals as faking ailments to avoid conscription (including men weakened by typhus or tuberculosis).Footnote 128

The central challenge posed to local authorities by the presence of wounded soldiers in Prague was, however, the risk of epidemics. In 1866, the Prussian invasion had been accompanied by an epidemic of cholera in Bohemia. A poster from the health commission of Prague instructed the inhabitants on the prevention of infectious diseases. First, the commission insisted that they should not fear an epidemic with an explicit reference to the 1866 precedent, still part of living memory: “we live today in very different circumstances than in 1866” because of more efficient prophylactic measures. The recommendations included advice on personal hygiene, on maintaining the cleanliness of streets (not throwing meal leftovers, no spitting), and encouraged drinking water from the water works and the fountain water in the Old Town, the fountain water being less reliable in the rest of Prague. If finding out that there was a sick person in the neighborhood, it was best to avoid all contact with them and their entourage.Footnote 129 These measures were, however, insufficient as wounded soldiers kept arriving into the city. As early as the end of September 1914, a memorandum warned against the risk of contacts between the wounded soldiers and the population for the spread of infections.Footnote 130 As statistics from the Military Command show, the men coming in carried with them different types of infectious diseases (typhus, diphtheria, dysentery, scarlet fever, trachoma).Footnote 131 Controls were in place at train stations and soldiers traveling were supposed to be quarantined for several days upon arrival even if they came from within the monarchy.Footnote 132 The city of Prague issued a warning to avoid any contact with the soldiers in the quarantine station of the Pohořelec barracks or to refrain from bringing them food or drink for risk of infection.Footnote 133

Hospitals were a particularly dangerous place for civilians to catch diseases brought by soldiers. As a case of cholera broke out in the Straka Academy in 1914, the institution asked for sick soldiers to be more systematically separated and sent to an infectious diseases’ hospital.Footnote 134 However, sorting measures could not always be efficiently carried out. The director of the German university clinic in Prague complained, for instance, about the state of soldiers who came into his service and had not been previously quarantined; they were full of lice and could not all be washed rapidly. The difficulty in communicating with them, as they were Bosnians, aggravated the situation. He warned about the risk of epidemics in these circumstances.Footnote 135 The director of Prague’s general hospital faced the same problem and also feared typhus contagion for the other patients from soldiers who had not been properly disinfected. The hospital was ill-equipped to contain the diseases that wounded soldiers brought back with them. It was one of the only establishments in Prague curing the civilian population and was already overflowed with soldiers: 420 beds were occupied by the military. The convoys arrived directly from the front with dirty clothes, flees, and lice without having spent time in quarantine or even a delousing station.Footnote 136

The long-term convalescence of some categories of wounded brought other issues to the fore. Some war-related injuries could not be easily cured and the growing number of war invalids required places to treat them. The organization of welfare for disabled servicemen saw a mix of grassroots private initiatives, semiofficial institutions and state authorities. During the last two years of the war, these initiatives were increasingly supervised by a centralized state welfare policy. The emphasis was on reintegrating injured soldiers into the workforce.Footnote 137 The Jedlička Institute in Vyšehrad, for example, provided rehabilitation programs. In the nearby Prague sanatorium in Podolí, gardening courses were organized for war invalids.Footnote 138 After 1918, the new Czechoslovak state introduced centralized welfare provisions for war invalids, but the pension amount was limited to about a third of a living wage.Footnote 139 In practice, war victims, including widows and orphans, still relied on the old Austrian form of welfare provided by municipalities, which was conditioned by an individual’s right of domicile (pertinency/Heimatrecht).Footnote 140

The wounded soldiers brought into the hinterland the reality of the battlefront. They were both the target of relief actions and a potential threat to the health conditions in the city. By 1918, the city, which had already devoted many of its public buildings to medical care, did not want another military hospital. A movement of opposition rejected the project of installing new Red Cross medical barracks in the imperial gardens, considering this move as an offense to the Czech national feeling.Footnote 141 This kind of ambivalence had characterized much earlier the attitude of Prague’s inhabitants toward another group coming from the battlefield zone into the city: refugees from Galicia and Bukovina.

Recent Arrivals: Refugees from War Victims to Scapegoats

From August 1914, the invasion of Galicia and Bukovina by Russian troops forced hundreds of thousands of people to flee into the hinterland of the Austro–Hungarian Empire, either because of evacuations from the army or for fear of the Russian advance. Some went to nearby Hungary, but most made their way to Vienna and the Bohemian Lands, as they were citizens of Cisleithania.Footnote 142 The first arrival of these refugees from the East in Prague in September 1914 put into contact populations that had not been much confronted with each other until then. In contrast to Vienna, a destination for many migrants from Galicia in the prewar era, this influx was not linked with the economic migrations of the pre-1914 period.Footnote 143 How did this encounter take place in urban space?

The first refugees arrived in Prague in September 1914 but, hindered by slow transportation, their numbers remained limited until November. By the end of October, Prague had only received 1,878 refugees, but their number had risen to 17,667 by the end of the year.Footnote 144 These figures are not entirely reliable because many refugees did not register with the police when they arrived, so that the actual number of refugees present in the city was probably higher. The Austro–Hungarian authorities had intended to separate them into two groups: those who had means to support themselves (bemittelt) and those who did not (mittellos). The latter group were to be sent to internment camps in Bohemia, Moravia, and Lower Austria, while the better-off were allowed to settle in big cities like Prague, Brünn/Brno, or Vienna. The refugees were also to be segregated according to nationality: Ukrainians were sent to villages and camps in Lower Austria and Carinthia, Poles to Bohemia and Moravia (and in the camp of Choceň/Chotzen in Bohemia), and Jews to Moravia, Bohemia, Lower and Upper Austria (with camps in Moravia).Footnote 145 This plan, however, did not materialize. As camps had to be built before refugees could be sent there, many of the people seeking refuge fled to the big cities, either in search of relatives (in Vienna, for example) or because they thought they could find work there. As a result, the refugees who found themselves in Prague at the end of 1914 were far from being all “bemittelt” and very diverse in nationality and religion (roughly half of them were Jewish and the nationality of the remaining non-Jews was not indicated at the time). Class played an important role in the consideration of authorities toward refugees. Refugees of Russian citizenship and Polish nationality who were in Prague were exempted from being sent in civilian internment camps and allowed to remain in the city if they were “socially higher standing persons,” even if they had no means to support themselves.Footnote 146

Galician refugees were considered by the Bohemian civilian administration as war victims on a par with the wounded soldiers. Refugees were allotted 70 heller a day per person. As municipalities were traditionally in charge of welfare, the Prague City Council played an important role in helping refugees. It made room for the impoverished ones in two municipal houses and a former army building.Footnote 147 Crucially, it distributed the state subsidy of the non-Jewish refugees (to be reimbursed by the state later). The Bohemian governor, Count Thun, published an announcement in the newspapers appealing to the population’s patriotic feeling to help with refugee relief. He called for donations of warm clothes and food as winter was coming, and expressed his confidence in the patriotic response in Bohemia.Footnote 148 This discourse on refugees as war victims can be compared, at this early point in the war, with the mobilization in favor of refugees in France and Great Britain.Footnote 149

From the start, voluntary associations complemented state and municipal support and often offered help divided along national or religious divisions. The Jewish community in Prague organized quickly to take care of coreligionists arriving from the East. They created a Help Committee as early as September 1914 and offered to take care of the Jewish refugees.Footnote 150 The local Jewish religious community paid the state subsidies directly to the refugees (as the municipality did for non-Jewish refugees). Their action was motivated both by solidarity with fellow Jews and a will to support the Austrian war effort. To house the destitute refugees, they rented out apartments in the Old Town and placed them in the Taussig almshouse.Footnote 151 The main association offering help to non-Jewish refugees was the committee of Polish refugees (Komitét uchodźców polskich), created by refugees themselves (local notabilities). A Czech–Polish secretariat was also created and a more official Regional Help Committee for War Refugees, especially Poles (Landeshilfskomittee für Kriegsflüchtlinge, insbesondere Polen). Rooms in Prague schools were reserved for refugee pupils receiving teaching in Polish or in Ukrainian (the Jewish community had also organized schools for Jewish refugees).Footnote 152 There was even a newspaper published in Prague in Polish (Wiadomości Polskie z Pragi) and a Polish section appeared in the Czech newspaper Národní listy.Footnote 153 Smaller nationality groups also established committees. A welfare committee for German refugees was born in September 1916, supported by the local German associations.Footnote 154 Other welfare initiatives emerged: the association of German private teachers, for example, collected money and distributed food and clothing to refugees.Footnote 155

A refugee cultural life developed in the city: a Polish-Jewish theater played in a hotel in the center, while the Czech National Theatre organized a Polish evening (playing music by Polish composers) to raise funds.Footnote 156 Polish priests celebrated mass in Prague churches. A parish chronicle in Žižkov mentions that with the presence of refugees in the suburb: “it was not a rare occurrence to listen to holy confession in Polish and Ukrainian.” It also recorded the names and life stories of several refugees, their professions, the masses they made celebrate, and other small facts such as the small girl who came to get waffles in the sacristy. The priest, however, highlighted the separation from the local population in burial rituals as the rule was to bury refugees in pits. Opposing Catholic and Jewish refugees, he spitefully noted: “yet, according to the rabbi, every Jewish refugee had his own grave here!”Footnote 157 The support for refugees, despite efforts from individuals and institutions, very quickly reached its limits.Footnote 158

Overall, help for these causes was not always as readily available as it was for wounded soldiers: fewer associations mobilized for this purpose. The organization of refreshments at the train stations for arriving refugees did not generate the same participation from the population as it did for wounded soldiers. Early in the war, the Prague City Council had to make an emergency purchase of 200 loaves of bread for hungry refugees arriving at Smíchov train station.Footnote 159 The Jewish community regularly distributed food to traveling refugees, but this activity stopped in 1915 when bread prices increased.Footnote 160 A physician wrote to the newspaper Prager Tagblatt in November 1914, shocked at the lack of any proper welcome at the Buschtiehrad train station for refugees who had to get warm water from the locomotive boiler.Footnote 161

Even in the official and private actions to provide for their welfare, the refugees were often regarded by the inhabitants of the Bohemian Lands as quite foreign, as evidenced in the way they occupied public space. Národní listy remarked their presence in large groups on the main boulevards and how they could be seen carrying pillows and blankets from the Old Town to the suburbs (see Figure 3.5).Footnote 162 Help was given with a degree of condescension toward these “less developed” countrymen. Another article quoted a Cracow newspaper mentioning the positive influence of their stay in Prague on Polish students who now used some Czech words and hopefully also learned the Czech work ardor (pracovitost).Footnote 163 Jewish welfare activists could also show a form of ambivalence toward Galician Jews. While they tirelessly contributed, both financially and practically, to the relief effort, especially at the beginning of the war, the assimilated Prague Jews sometimes complained about the backwardness of the more traditional Galicians. The fact that Hasidic men wore side-curls and long coats raised concerns over antisemitism. They expressed the same hopes as the Czechs that this exposure to Western culture would somehow make them abandon their customs.Footnote 164 Even a positive description of the newcomers in Prague streets tended to exoticize them, depicting “long bearded Galician Jews with their long caftans” and of the more rarely seen Galician peasants, “several of them wearing their colorful national costume and walking on the pavement with their solid high boots.”Footnote 165 The physical presence of the refugees rendered tangible implicit hierarchies of “civilization” between East and West in East Central Europe, with Prague residents of any nationality positioning themselves firmly at the most “civilized” end of the spectrum.Footnote 166

Figure 3.5 Refugees in Břevnov (1915)

The refugees also appeared on the street as a visible sign of the Empire’s defeats on the battlefields. An anonymous letter mocked the official propaganda, ironically proclaiming: “For sure we win, that’s why refugees come from Cracow.”Footnote 167 A refugee was arrested for spreading rumors in the fall of 1914. He had announced in a pub of the New Town that the army was going to lose.Footnote 168 Through their stories of war experience but also through their mere presence, refugees potentially challenged official news on the progression of the battlefronts and therefore helped undermine the trust in the state. They also potentially highlighted the state’s shortcomings in the treatment of war victims. In 1916, when refugees escaped from the Choceň internment camp and came begging into the city, officials urged the population not to believe their stories, worried that they might “discredit the state refugee welfare.”Footnote 169 Finally, some Ukrainian-speaking inhabitants of Galicia were suspected of harboring pro-Russian tendencies and of spying in the main cities of the Empire.Footnote 170 For all these reasons, the Prague authorities were attempting to limit contact between the local population and the refugees.

Prague residents themselves increasingly tried to enforce distance in daily interactions. Public space was the scene of some openly hostile relations. Several refugees were attacked or beaten on the street.Footnote 171 As early as April 1915, the police noted concerns about the refugees, “who are designated by the lowest classes as mainly responsible for the rising food prices.”Footnote 172 Their presence in shops was sometimes resented. For example, a group of shopkeepers from a shopping arcade wrote to complain to the Prague police about the “flood of refugees,” not only endangering their safety but also turning away other customers: “with this flood of refugees, who are absolutely not used to standing in line (řádné vystřídání) and order, attendance by the public buying or passing through is made impossible.”Footnote 173 Growing food shortages also led to new tensions in the long queues to get food. Refugees signing as “Poles from Brewnow” (a Prague suburb) wrote to the Polish refugees’ Committee with complaints that Czech store owners refused to serve them, claiming that they had nothing for Poles.Footnote 174 In February 1917, separate days and times for shopping were introduced for refugees in the municipal flour selling points.Footnote 175 Jewish refugees complained in Vienna in 1917 that they were prevented from buying food in Prague. Police investigations in several Prague neighborhoods showed that the refugees were indeed often excluded from queues by other buyers. The police did not seem very keen to intervene and sometimes even defended the other shoppers’ behavior (their fear of being contaminated by vermin, for example).Footnote 176 In a context of scant resources, Praguers expressed difficulties in sharing spaces as much as in sharing food supply.

The spread of epidemics was a major concern for the city’s authorities, which perceived the refugees’ hygiene standards and health conditions as a threat. The municipal physician even recommended that the public avoid all contact with refugees in order to prevent infections.Footnote 177 Municipal authorities worried about their lack of cleanliness and required them to be regularly checked by the municipal physicians.Footnote 178 Yet, the poor hygiene conditions in the makeshift buildings where the city housed them could also explain the refugees’ poor health situation.Footnote 179 The Prague Council created a special delousing station in Bulovka for refugees in May 1916. The process was to last for a maximum of three hours: the refugees had to take off their clothes, which were disinfected, and had their hair examined and shaved if lice were found. Finally, they were washed in hot water. The physician recommended patience, and that violence should be avoided at all cost.Footnote 180 This recommendation suggests that many refugees were reluctant to go along with this treatment. They had to undergo many regular medical inspections and developed strategies to avoid this encounter. A physician going on rounds in the suburb of Žižkov complained that many were absent from the flats where they were supposed to live, and that he could examine only two thirds of the persons registered.Footnote 181 Fear of epidemics led the city to set up protective disinfections. A newspaper reported in March 1917 that due to a potential typhus epidemic among Galician refugees, families had been transported to Bulovka to be disinfected, and would only be taken back to their homes when the risk of infection was eliminated.Footnote 182 For hygiene concerns, the municipality thus highly regulated the refugees’ liberty of movement within the city. Concern over the spread of disease easily turned into a racialized discourse against East European Jews, seen as primary carriers of disease.Footnote 183

The mere presence of refugees in the city was often perceived as hostile and endangering the “health” of the community. The mayor of Karlín complained about the refugees in terms very similar to those used by the mayor of Král. Vinohrady (see text box), accusing the “fluctuating creatures” of incessantly moving from one apartment to another, thus rendering medical control very difficult.Footnote 184 Authorities in Žižkov declared that 8,000 Jewish refugees were staying in the neighborhood, driving up prices and putting the health of the community at risk in apartment buildings, tramways, and “other social places,” avoiding work and conscription into the army; officials finally recommended that they should be kept completely separate from the rest of the population.Footnote 185 The public health concerns mixed with antisemitic rhetoric were directly linked to the experience in the streetscape: at market halls, on tramways, and in apartment buildings. As Stephanie Weismann argues, othering was essentially a sensorial process – antisemitic conceptions considered Eastern Jewish presence as a sensory offense to civilization coupled with a fear of contamination.Footnote 186

Refugees and the Municipality

The mayor of the suburb of Král. Vinohrady complained about the Jewish refugee presence in urban space. In a public announcement to be posted on the streets, he called for a precise list of those staying in the borough to be given to building managers and forbade the raising of poultry: “The number of Galician immigrants of Jewish faith in Král. Vinohrady is constantly growing. Some houses are full of them […] These Galician emigrants are very mobile and fully use our public facilities. In particular, they come in flocks to the main market hall and touch the merchandise. Demanding a very low price for it, they then go to another stand.”Footnote 187

As we can see, the mistrust toward refugees progressively targeted, more specifically, Jewish refugees. While at the beginning of the war, the discourse on refugees tends to mention them as “Galician refugees,” the term “Jewish” grows more frequent toward the end of the war. This did not necessarily reflect the evolution of their proportion among refugees at the time: from around half in the last months of 1914, the proportion of Jewish refugees went up to 68 percent in August 1915, but down to 38 percent in March 1917. As for non-Jewish refugees, they were in majority Polish-speaking. In March 1917, for example, there were 6,621 Poles, 990 Ruthenes, 928 Germans, 90 Hungarians, 175 Czechs, and 435 others.Footnote 188 After the war with Italy started, a few hundred refugees (682 at the highest point) also came from the South-Western regions (hardly any of them relying on state support, however). The presence of the refugees in the city followed the variations of the Eastern front. After the Austrians and Germans recovered territories in the East in the summer of 1915, some of them went back home. The Brusilov offensive in 1916 brought a new wave to Prague. A few thousand refugees from the internment camp at Choceň also came to Prague around that time, which explains the increase in destitute refugees. They wanted to flee the camp and its appalling living conditions: the poor accommodation and the spread of typhus led to a high mortality rate there.Footnote 189 The number of refugees gradually diminished after that until the end of the war. The highest point was in June 1915, when 24,295 refugees were in Prague. By May 1918, there were only 2,688 refugees on state support remaining in the city (including 2,415 Jews).Footnote 190

At several points during the war, the Prague municipal authorities attempted to limit the number of refugees in the city. As early as January 1915, the city was officially closed to further arrivals of refugees, which of course did not prevent them from coming.Footnote 191 The authorities tried to send them to internment camps and encouraged their repatriation when Austro–Hungarian troops recovered Galicia in 1915. Toward the end of the war, municipal authorities repeatedly demanded their departure.Footnote 192 The public also condemned their continuous presence. As an example, this anonymous letter was sent in September 1917 to the Governor: “We workers from Prague demand for the last time that the Governor of Bohemia Count Coudenhove expel all the refugees from the East, because all these cities are free, at the most until the end of October, otherwise we will stop work and it could come to scandals […].”Footnote 193 In September 1917, an article in the Social-Democrat newspaper Právo lidu demanded that refugees leave because of the “universal hatred that prevails against them” due to the difficult food supply situation.Footnote 194 The refugees’ reluctance to go back to their former home could be explained by the destruction the war had brought on villages and towns in Galicia, and the family disruptions caused by the conflict. Many towns in Galicia and Bukovina were completely annihilated. Some refugees had managed to find a job or were not healthy enough to undertake the journey. The higher proportion of Jewish refugees who stayed behind can be explained by the fear of pogroms in the region (and the rumors of actual violence filtering through). Some of them even came back after November 1918 and the pogroms in Galicia.Footnote 195 Applications to the police for a prolonged stay in Prague recount the traumatic aspect of the departure from Galicia and the often difficult living conditions in Prague. Many refugees were too sick to travel (due to food shortages) or did not want to leave sick family behind. These petitions also show a certain degree of integration into Prague society through work.Footnote 196

The antisemitic character of both the Prague City Council’s policies and the local population’s reactions grew increasingly visible as the war went on. Jewish refugees were banned from public tramways in 1917.Footnote 197 As with earlier measures of exclusion, this was justified by a concern for public health and the spread of disease. We see here the shift from measures concerning all refugees to a ban targeting only the Galician Jews. This measure was however revoked after a public outcry.Footnote 198 In October 1918, the Prague Municipal Council reported that the only refugees remaining in the city were Jewish ones, accusing them of profiteering and taking advantage of the state subsidies they were getting. The Council’s recommendations included suspending state aid and the distribution of rationing tickets to refugees. The municipality of Žižkov had introduced a similar measure shortly before that was repelled by the Interior Ministry.Footnote 199 The Council’s measures constituted a clear shift toward overt antisemitism. To be sure, the clearance of the Jewish ghetto in Josefov at the end of the nineteenth century already revealed the intertwining of modern hygienic concerns about public health with antisemitism.Footnote 200 Prejudices against Jews on economic grounds were not new in Czech society either.Footnote 201 But, the war exacerbated this discourse and, for the first time, the Municipal Council envisioned measures of exclusion. The official classification of refugees according to their nationality, separating Jews and non-Jews, had also created a precedent for officials. As we have seen, the prejudices among the public targeted the visible presence of Eastern Jews in public space, which was a new phenomenon in the Prague context.

The creation of Czechoslovakia in 1918 gave a new pretext to demands for the refugees’ departure among the Czech public, as the refugees present on the Czechoslovak territory were no longer considered as members of the same state and could thus be expelled as foreign nationals. In 1919, the young Czechoslovak state took measures to force the remaining wartime refugees to leave.Footnote 202 Exceptions were only granted to people who were too sick to travel or those who were owners of a shop or economic activity.Footnote 203 Even then, the extensions were often only for a few months. The new state stopped providing financial support for them. The letters sent to the Prague Police Headquarters to ask to have the right to stay in Prague show that the refugees’ official right of domicile (pertinency/Heimatrecht) in Galicia, which made them Polish citizens, often did not correspond to their life stories or their feelings of belonging.Footnote 204 They had managed despite war upheaval to make a home for themselves in Prague. By going “back” to their supposed home town, some of them would go to a country where they had no living relatives, and no job prospects. Many explained that their town or their houses had been destroyed during the war. A woman, for example, mentioned that all her furniture in Galicia had been taken by soldiers: “I have no alternative but to stay here where I have a modest apartment with borrowed furniture from the neighbors but where my three children and I can rest our heads.”Footnote 205 All those letters show how the war made citizenship both a more relevant category in people’s lives, but also the object of more attempts to work around the regulations by ordinary people, who attempted to shape their own relation to the state and their new city.Footnote 206