The first few years of life are an optimum point at which to deliver cost-effective preventive interventions to ensure long-term nutritional health(Reference Irwin, Siddiqi and Hertzman1). Children in this early years period are a highly vulnerable group, particularly susceptible to the effects of poor nutrition(2) which can have short- and long-term implications for health and social well-being(3–Reference Stein8). While children have an innate ability to self-regulate dietary intake this can be overridden by feeding practices(Reference Birch9). Young children model their feeding behaviours on those around them(Reference Rudolf6, Reference Birch9), suggesting that the behaviour of parents, carers and peers can have a significant influence on the establishment of life-long healthy eating habits during this period(2). Changes in family composition and working patterns have seen increasing numbers of children under 5 years spending time in child care, with some relying on it for their entire nutritional intake(10). The introduction of free child-care places for all 3- and 4-year-olds has also seen the number of registered child-care places in England almost triple in the last decade(Reference Crawley4). Thus nurseries, pre-schools and childminders have an important role to play in contributing to the good nutrition, health and development of children during this formative period. However, despite significant investment in child health, nutrition in the so-called early years period (ages 1 to 5 years) has been largely overlooked and the nutritional status of this age group in England is suboptimal(5, 11). Many under-5s are still deficient in key nutrients and consume too much salt, not enough meat or total fat, and insufficient energy(7, Reference Shepherd12, Reference Turnbull, Lanigan and Singhal13). At the same time, the prevalence of childhood obesity (including overweight) in boys and girls aged 2–15 years reached 31 % and 29 % respectively in 2008(Reference Craig, Mindell and Hirani14). These poor outcomes have resulted in calls for immediate action at national and local levels to improve the food offered in child-care settings(5). Unfortunately recent reviews of the quality of food provision and practice in nurseries have indicated high variability, with provision falling far short of current nutritional guidelines(5, 15, Reference Denton16). A nutritional analysis of menus in 118 nurseries across England, conducted in 2010, found that none were 100 % compliant with nutritional guidelines for under-5s in child care(Reference Crawley4, 10). The study exposed the overuse of cereals and bread-based snacks resulting in excessive salt and sugar intake, excessive fibre levels which can cause digestive problems or inadequate mineral absorption, and insufficient energy provision(10). This is consistent with findings of a local survey of twenty-nine pre-school settings across the regions of Merseyside and Cheshire where staff were relying on high-fat/sugar snacks to ensure children consumed sufficient energy(Reference Mwatsama17). Furthermore, an online survey of over 2000 parents and nursery workers across England and Wales in 2008 found that foods now banned in primary and secondary schools (including processed meats and fried foods such as potato chips) were still being served to younger children. Some nurseries were spending less than 25p per meal per child, only 8 % of nurseries ever served oily fish and only a quarter provided regular access to drinking water(15). These reports all recommended the development of a single source of age-appropriate nutritional guidelines, improved training and support for child-care workers and better regulation of the quality of food in child-care settings(10, 15, Reference Mwatsama17).

National child nutrition policy in the UK is grounded in a set of policy commitments dating from the 1940s, driven by post-war concerns for inadequate nutritional intake(Reference Stein8). The early years period has been systematically overlooked in recent key policy documents(18–21), with attention focused on infants or school-age children(5). Only the Food and Health Action Plan(22) included a significant emphasis on the role of diet in the early years with proposals for the Healthy Start Scheme, established in 2006. Best practice guidelines and quality control mechanisms for early years food provision also currently provide inadequate leverage to drive improvement. The Government's Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS)(7) provides the statutory framework for child-care providers with a requirement to promote the achievement of the goals of the Every Child Matters Strategy(23), including providing healthy and nutritious food and encouraging children to make healthy choices(7). However, while the EYFS stipulates that children should be provided with healthy, balanced and nutritious food(24) it does not provide further definition, leaving it open to interpretation(25). Moreover the latest nutritional guidelines for this age group in England, published in 2006(Reference Crawley4), are now considered out of date(3) and practitioners have at their disposal a confusing array of information from both Government(Reference Rudolf6, 26–29) and independent bodies(25, 30–32).

The previous Government administration commissioned the School Food Trust (SFT) to establish the Advisory Panel on Food and Nutrition in Early Years (APFNEY). Its task was to undertake a review of food and nutrition in settings providing care to children aged 1 to 5 years, offering a valuable opportunity to improve policy coherence, review the structural and resource requirements for policy implementation and incorporate the recommendations into existing and future strategies. However in its focus on reducing the national deficit, the current Government (which took office in May 2010) proposes deep cuts to public spending(33), limiting the financial capacity of local, regional and national stakeholders to respond to policy change. Nevertheless the consultation process for the new Public Health White Paper provides an important policy window for stakeholders to draw political attention to the issue of food provision in early years settings and defend existing policy commitments.

Regional policy development has been constrained by the lack of national policy direction and current policies in the South East reflect the limitations of national policy, with insufficient focus on the early years period and a lack of development or promotion of best practice guidelines. The South East Health Strategy(34) has the promotion of physical and mental well-being in children as a core theme; however actions are again focused on infancy and school-aged children(34). Although the Department of Health South East has developed a Draft Infant Feeding Framework for Under 2's(Reference Biggs35) it is yet to develop similar guidelines for older age groups.

Policy development at a local level has been more progressive, driven by the establishment of a number of statutory partnerships for health improvement under the umbrella of the Local Strategic Partnership. This has facilitated the development of a cross-organisational Health and Wellbeing Strategic Plan for Southampton(36). This document acknowledges the importance of intervention in the early years, setting a strategic ambition to support all children to have a healthy start in life. There is coherence with other cross-organisational strategies which mirror this ambition(37, 38). Southampton's Healthy Weight Strategy also includes a number of objectives specifically targeted at child-care settings to improve food provision, implement food policies and increase the provision of healthy eating activities(39) supported by the development of a Healthy Early Years Award Scheme.

The present paper makes the case for supporting existing political commitments and consolidating existing structures in England to improve healthy food provision in early years settings. It analyses the role of key organisations in the implementation of local and regional policy, as exemplified by early years food policy and practice in key settings in the city of Southampton, England.

Methods

The study focused on policy and practice relating to food and drink provision for 1- to 5-year-olds but excluded that relating to younger infants. It included child-care settings registered by OFSTED (Office for Standards in Education Children's Services and Skills), i.e. day-care nurseries, pre-schools and childminders, but excluded non-registered child-care providers, foster carers, children's homes or hospitals. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. The local Health Research Governance team in Southampton also provided approval for the project.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with key stakeholders in the city of Southampton and Regional Government Office to investigate factors influencing food policy and practice in child-care settings and to elicit examples of innovative practice. The one-to-one interviews were held between June and August 2010 and each lasted 25–40 min. Purposive sampling was used to recruit participants representing a broad range of perspectives, including child-care providers, managers and catering staff from settings in deprived and affluent areas (identified using the Index of Multiple Deprivation(40)) and of varying quality of provision (identified using the OFSTED Inspection scores(41)). An interview guide was developed, in collaboration with five local experts, to identify key themes relating to nutritional policy development and implementation and capture local issues.

All participants were provided with an information sheet and consent form prior to interview. Signed copies were retained by the researcher (verbal consent was obtained for a telephone interview). Interview recordings were transcribed verbatim to enable familiarisation with the data. Information from the interviews was mapped onto the thematic framework presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Framework of issues relating to food policy development and implementation

Adapted from references (Reference Fulop, Allen and Clark50) and (Reference McLachlan and Garrett54).

Results

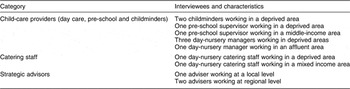

A total of thirteen interviews were conducted in eight child-care settings (four nurseries, two pre-schools and two childminders). They are described in Table 2.

Table 2 Categories and characteristics of interviewees in Southampton

Child-care settings’ food policy and menu planning

Only one out of the eight settings had a specific food policy in place. This is consistent with a local review(Reference Davies42) which identified a lack of city-wide or setting-specific food policy, but contrasts with findings from a number of other surveys across the country which found the majority of providers had a food policy(Reference Alderton and Campbell-Barr43, Reference Parker, Dexter and Kelly44). All child-care settings had made a considered attempt to provide healthy food although their approach varied. This differs from the findings of a survey conducted in Kent 5 years ago which concluded that the routine consideration of the nutrition needs of children was rare(Reference Alderton and Campbell-Barr43). All four of the day-nurseries undertook formal menu planning although their influence over menu content varied depending on the catering arrangements. One nursery had a dedicated cook with total autonomy over menu development. In contrast, child-care settings which relied on external catering providers, such as school kitchens, had little or no influence over menu planning. This is consistent with the findings of a survey in Liverpool which highlighted that Children's Centres reliant on school kitchens had limited opportunity to influence menu development(Reference Lloyd-Williams and Bristow45). Menu planning was much less systematic among childminders and in pre-schools, who generally only provided snacks. This differential approach to menu development is consistent with the findings of a number of other surveys which found varying levels of staff and parental involvement in the planning process(Reference Alderton and Campbell-Barr43, Reference Lloyd-Williams and Bristow45).

Food provision and mealtimes

While the range of food and drinks on offer was broadly similar across settings, the approach to food provision differed significantly. One childminder routinely offered breakfast whereas a Sure Start Nursery purposefully did not provide breakfast to encourage parents to take responsibility. While all day-care nurseries and pre-schools offered milk to children, there were inconsistencies with some providing semi-skimmed, others whole milk. The majority of settings had strategies for introducing new foods and dealing with rejection by children; however some providers were concerned practice did not always match policy:

Some nursery nurses don't persevere to introduce new foods; they're too quick to give up due to the pressured environment.

This concern was reflected in an earlier survey which suggested a lack of skills to deal with food rejection was a major barrier to introducing healthier foods(Reference Alderton and Campbell-Barr43).

Although providers were accommodating a wide variety of special diets, none had received specific training and most suggested that parents were the best source of information on how to deal with their children's needs. Accommodating religious dietary requirements was a common challenge. Most approached this by offering vegetarian alternatives. One setting had considered introducing halal meat but concluded that costs currently outweighed demand.

Policies on staff interaction at mealtimes varied. In some day-care settings staff always ate the same foods with children whereas in others they were discouraged from doing so. This reflects the diversity of practice evident in previous research(Reference Alderton and Campbell-Barr43, Reference Lloyd-Williams and Bristow45, Reference Macklin and Charnley46).

Communication and collaboration between actors

Most providers agreed that parental education was vital to improve diet in the early years; however many providers raised concerns regarding their role in the provision of this education. Both private day-care providers and childminders highlighted potential tensions between practitioners and parents in privately funded settings where parents, as customers, hold the power to influence food provision and practitioners may feel disempowered to influence parental choice for fear of losing their custom. A recent national survey revealed similar tensions(10). In contrast, publicly funded settings appeared more willing to discuss healthy eating with parents, although some still had concerns, noting that:

it's a bit of a problem talking to the parents … some of the children really need to be here and some parents … need support and … if you're too judgemental I think then you'll put a lot of people off.

This highlights a potential conflict of interest in integrated settings (bringing together health, social services and other agencies) such as Children's Centres, where child protection issues may take priority over objectives for health improvement. This was echoed by a Regional Adviser who observed that:

for a lot of people … child protection … is a priority … not nutrition.

Communication regarding healthy eating between child-care providers and other services was limited. While the Local Authority provided all maintained nurseries with an Early Years Development Manager with a remit to advise on healthy eating, this resource was not available to private nurseries or childminders. Collaboration with local Public Health Services, such as health visitors, dietitians, nutritionists and oral health practitioners, also varied between settings. One kept regular contact, others sought advice on an ad hoc basis and some could not recall receiving any support from these services. This suggests that local access to and utilisation of professional nutritional advice differs between providers. Opportunities for vertical communication between local, regional and national early years policy leads are available. The Department of Health South East has a Healthy Weight Team which provides a channel of communication through direct liaison and the coordination of professional networks. However the team manager identified a number of potential barriers currently constraining progress in supporting the early years nutrition agenda, including a lack of coherent guidelines, the diversity of the child-care workforce and competing public health priorities.

Knowledge and training

The plethora of information sources, lack of authoritative guidance and resulting confusion regarding best practice on nutrition for the early years has been recognised in a number of recent key reports(3, 10, 15, Reference Alderton and Campbell-Barr43, Reference Caraher, Crawley and Lloyd47). The most common sources of information used by practitioners were childminding magazines, the Internet and parents. Only one practitioner was aware of any of the primary sources of nutritional guidelines identified in the APFNEY Provisional Review(3). This is consistent with the findings of a local review which found that staff lacked knowledge on the latest food and nutritional guidelines(Reference Davies42). Perhaps of greatest concern is the lack of knowledge among catering professionals in this sector. Neither of those interviewed had received specialist training. One commented:

all these kids’ nutrition is reliant on me and I'm just fumbling in the dark.

This is consistent with the findings of surveys in Liverpool and Cheshire and Merseyside which found that training for catering staff was not considered a priority(Reference Mwatsama17, Reference Alderton and Campbell-Barr43, Reference Parker, Dexter and Kelly44). These surveys also highlighted a lack of awareness of training opportunities and difficulties in releasing staff to attend training, both issues which were also evident in Southampton. Participants identified a range of specific issues on which they required further guidance. These included: recommended daily nutrition requirements, daily and weekly menu planning, ideas for healthy lunchboxes and healthy recipes, advice on portion sizes, how to introduce oily fish and catering for religious/cultural and other special dietary needs. These mirror many of the topics identified in the APFNEY Preliminary Report(3) suggesting that these are generic concerns for all practitioners. Despite their apparent lack of specific knowledge, many providers in Southampton thought mandatory healthy eating training would be unnecessary. Some suggested that most practitioners would not have the opportunity to implement the knowledge gained. Views on the introduction of mandatory nutritional guidelines were distinctly polarised. Some settings were supportive, arguing that:

for too long there hasn't been any guidance … bring in some standards now and enforce it.

However childminders were opposed to the idea, citing that the additional pressure and paperwork would cause resentment and may force some childminders out of the profession. Others voiced concerns over the approach and the practicalities of enforcement, suggesting it would require some settings to drastically change their menus and recommended an incremental and flexible approach to implementation.

Discussion

A number of recent reports reiterate recommendations for national policy and funding to be focused towards the under-5s in order to maximise the opportunity for good nutritional health(Reference Wilkin and Voss48, Reference Marmot49). National policy regarding local children's service provision has facilitated coherent policy making between organisations at a local level: the replication of objectives for the improvement of early years nutrition in a number of local cross-organisational strategic documents in Southampton indicates that there is growing consensus among decision makers of the relative importance of this issue. However although there is a wealth of evidence on the implications of poor nutrition in early years, providing a solid rationale for policy prioritisation and resource allocation, this has not on the whole resulted in a proportionate shift of attention and resources to the provision of nutritious food for this age group at either a national or regional level.

Efforts to sustain healthy food policy and practice must be maintained, and coherent, evidence-based guidance and practical tools to facilitate effective practice must be provided, all the while ensuring that existing resources are used efficiently and fully exploited. For example, the need for nutrition training expressed by early years staff has been acknowledged at a strategic level both regionally and locally but is yet to be fully met through the provision of a coordinated and universally accessible training programme. The varied views on mandatory training expressed in the interviews and literature suggest further consideration should be given to the need for a universal national training programme. Increasing opportunities for communication and collaboration offer cost-effective methods of improving efficiency, enabling knowledge and skills transfer and streamlining processes to avoid duplication, which is essential in periods of financial austerity(Reference Fulop, Allen and Clark50). The role of parents as stakeholders in food provision should not be overlooked and communication between providers and parents can also be improved.

While targets help drive policy implementation, monitoring performance requires resources and the capacity for regulation is an important consideration. While the OFSTED inspection process offers an existing mechanism in which to incorporate the regulation of food standards, this would have resource implications that would need to be incorporated into any implementation plans(10, Reference Mwatsama17, 25, Reference Macklin and Charnley46).

Study limitations

The present study has a number of methodological limitations that may affect the applicability of the findings to the study setting and the transferability of results into other contexts. The number of child-care providers interviewed represented only a small proportion of the total workforce in this setting (eight out of a total of 513 or 2 % of registered child-care settings in Southampton)(38). While a purposive sampling strategy was used to recruit child-care providers who varied according to their type, location and quality rating, practical issues limited the extent to which these sampling criteria were fulfilled. Thus the opinions and practice reported here are not necessarily representative of those across Southampton. A further study of a larger sample, purposefully selected to reflect the ratio of child-care providers within the local workforce according to a broader range of variables, would provide a richer source of data, enabling deeper exploration and validation of the issues identified and increasing the applicability of the findings to the local context. Convenience sampling rather than purposive sampling had to be adopted in some instances. This may have resulted in selection bias as participants who made the effort to accommodate the interview may have different perspectives from those who declined. Moreover, although parents play a central role in supporting healthy eating practice both within and outside the home(Reference Crawley4) and as such represent a key stakeholder in this agenda, it was not possible to incorporate their views in the present study. The views of parents on the issues identified here should be captured by further research and incorporated into any policy response. Another limitation is that the interviewer had previously worked at a strategic level in the area and although precautions were taken to emphasise her independence, some interviewees, aware of her prior position, may have been reluctant to reveal practice that may be perceived undesirable. Also, healthy eating practices in child-care settings have had significant recent publicity with many high-profile media articles criticising current practice(Reference Defries51–Reference Shepard53), possibly increasing participants’ sensitivity to the issues and making them reluctant to reveal areas of perceived weakness. However, although the accuracy of responses relating to healthy eating practices may be questionable, the provision of sample menus and observations within settings provided evidence with which to validate responses and suggests that most accounts were accurate. The inclusion of an additional observational study to assess actual as well as reported behaviour would provide further opportunities for validation.

Finally, the relatively narrow geographical focus of the study also affects the potential transferability of these findings beyond the study setting. Although the issue of food provision in child care is globally relevant, policy makers within and outside the UK should consider how their population compares with the study population with respect to a variety of contextual factors such as demography, organisational structures and support systems when determining the relevance of the findings to their own areas. The transferability of the findings beyond the UK will also be dependent on a number of strategic factors such as variations in child-care practice and the relative proportion of care received in formal child-care settings.

Conclusions

The present study provides insight into the policy and practice of food provision in a range of child-care settings which both corroborates and challenges the findings of previous nursery-based research. It is relevant and timely, having been designed to contribute to the national review of food and nutrition in early years which has recently been completed. There is a wealth of evidence on the importance of proper early nutrition to provide the building blocks for life-long health and well-being, both from a behavioural and physiological standpoint. Existing early years child-care settings are an ideal place (outside the home) for providing a strong foundation in nutritional health and dietary habits for young children.

A range of recommendations have been made for action at a regional and local level to address the potential barriers and exploit the existing capacity and commitment to improve nutritional provision in child-care settings. These include: strengthening local consensus on the importance of the issue and developing a strategy to secure wider support across regional public sector bodies; conducting an early years nutrition training needs assessment; and rationalising and strengthening regional and local support structures. However, the long-term benefits of achieving optimum nutrition in the early years can only be secured through the coherent efforts of national, regional and local policy makers, child-care practitioners and parents. Existing commitment and capacity to achieve this objective at a local and regional level must be supported and matched at a national level with the acceleration of policy development including quality control and support mechanisms.

Acknowledgements

H.B. received support from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, National Advisory Panel on Food and Nutrition in Early Years Settings, Department of Health South East, Wessex Deanery, NHS Southampton City and Southampton City Council to undertake the research. There are no conflicts of interest to report. H.B. designed the study, carried out the data collection, analysis and interpretation, and wrote the manuscript. C.K. provided project supervision and contributed significantly to the development and writing of the manuscript. Both authors have seen and approved the contents of the submitted manuscript. The authors would like to acknowledge the interview participants who generously gave their time and provided invaluable insight.