Book contents

- The Hegemony of Growth

- The Hegemony of Growth

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures and Tables

- Book part

- Glossary

- Introduction

- Setting the stage

- Part I Paradigm in the making

- Part II Paradigm at work

- Part III Paradigm in discussion

- Epilogue

- Conclusion

- Archival sources and select bibliography

- Index

- References

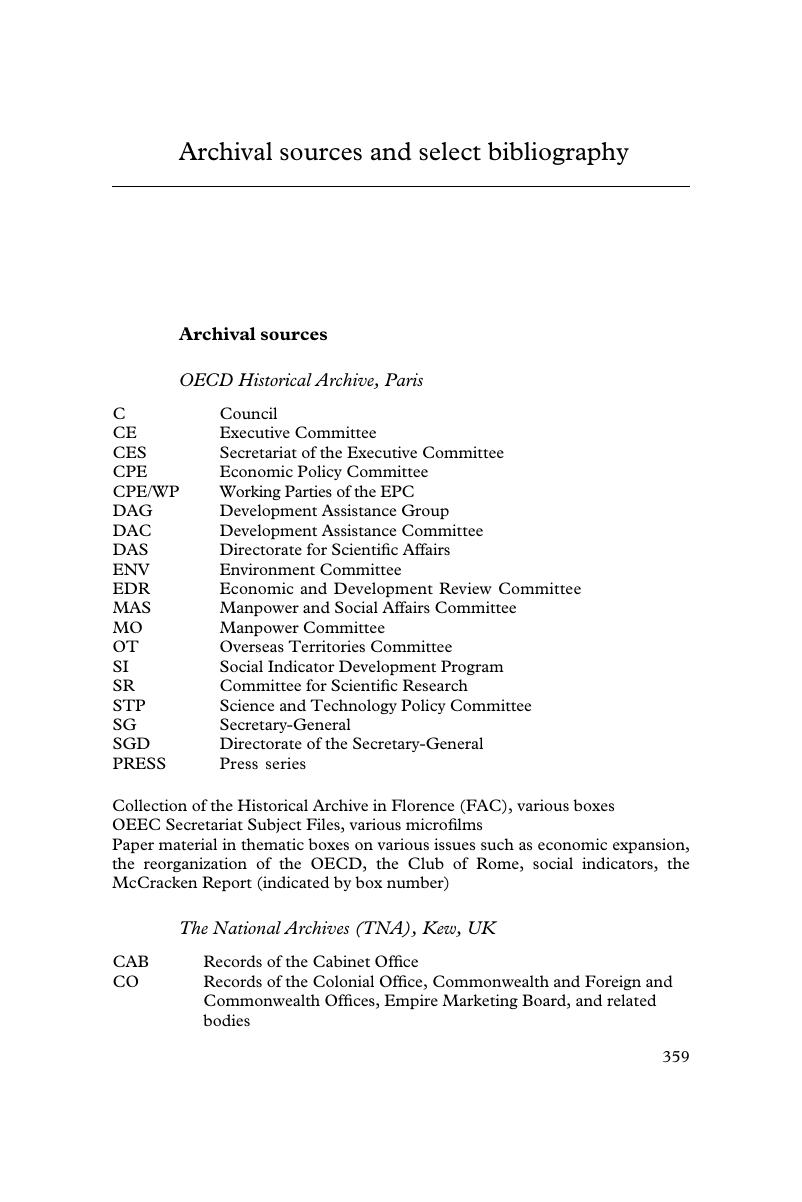

Archival sources and select bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 May 2016

- The Hegemony of Growth

- The Hegemony of Growth

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures and Tables

- Book part

- Glossary

- Introduction

- Setting the stage

- Part I Paradigm in the making

- Part II Paradigm at work

- Part III Paradigm in discussion

- Epilogue

- Conclusion

- Archival sources and select bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Hegemony of GrowthThe OECD and the Making of the Economic Growth Paradigm, pp. 359 - 374Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2016