Titus Kaphar’s painting To Be Sold depicts Princeton University’s president Finley (1761–66), partially obscured by shredded, hanging canvas strips affixed with nails (Plate 2).Footnote 2

Plate 2 Titus Kaphar. To Be Sold, 2018. Oil on canvas with rusted nails. American, born 1976. Princeton University Art Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund.

To Be Sold as a research-creation is both art object and historiographical critique. It aesthetically and ethically intervenes in a chain of historical objects: an eighteenth-century oil portrait of president Finley, attributed to John Hesselius (1728–78), hung in the Princeton University Faculty Room. In 1870, Charles Walker Lind used this portrait as the basis of his own oil portrait of Finley. Kaphar’s To Be Sold triples this painterly genealogy by imitating Lind’s painting.

The painting’s title, To Be Sold, engages documentary historical evidence. It refers to a 1766 newspaper headline announcing the sale of six enslaved persons of African descent at Princeton’s Maclean House, as part of the dispersing of president Finley’s estate. Kaphar painted the advertisement in eighteenth-century looping, rust-colored script on canvas, tore it, and nailed strips to his portrait of Finley.Footnote 3 Tucked safely into an arched space, Kaphar’s Finley reacts with his right eyebrow skeptically tugging upwards at a muscle in his forehead. The word “SOLD” ripples downward from the center of Finley’s face. Kaphar often uses the technique of shredding and nailing “documents.” He affixes one piece of documentary evidence – a reproduction of a historical text – to another – a canvas that references a historical painting. He explains his use of nailing by referring to minkisi minkondi: “the gesture of nailing pieces of canvas into the image is inspired by the Congolese tradition of Nkisi power objects, and it is symbolic of both faith and power in the object itself.”Footnote 4

Kaphar’s To Be Sold draws on the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century aesthetics of Anglo-European portraiture and advertisements of the enslaved.Footnote 5 It also draws on the aesthetics and gestures of Kongolese power figures and their ritual contexts.Footnote 6 In the gesture of nailing, Kaphar participates in the bristling power of ritual gesture associated with minkisi minkondi. Kongolese minkisi minkondi (sing. nkisi n’kondi) are repositories of power (Plate 3).Footnote 7 Whatever the form of the n’kondi, it is activated by a small amount of “medicine” within, usually tucked behind an orifice in the belly, capped by a mirror. Some minkondi are also ritually impaled with blades called mbau, each representing “an appeal to the force represented in the figure, arousing it to action.”Footnote 8 That action was often one of healing or oath-making.Footnote 9 Each object nailed or tied upon the power figure was evidence of a miniature story of a desire to act or make an oath, empowered by minkisi, or spirits. As Wyatt MacGaffey puts it: “People depend on minkisi to do things for them, even to make life itself possible.”Footnote 10

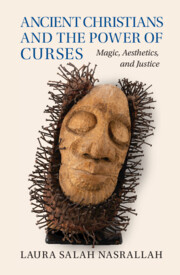

Plate 3 Power Figure (Nkisi N’kondi). Nineteenth to early twentieth century. Wood with iron, cloth, mirror, leopard tooth, fiber, and porcelain. 45.7 × 20.3 × 8.9 cm.

Minkondi are also power-figures in a political sense: they are produced because of legal and social concerns, and they are agents in conflicts. Minkondi can pursue a culprit. They are “regulatory instruments” that can heal, mend violence, or produce death and “adjudicators with the capacity to attack foes or foster peace.”Footnote 11 A seventeenth-century document indicates that a Belgian officer on campaign in the Kongo determined that one n’kondi had a “very great reputation” and considered it an important hostage. After its capture, the officer stored it in a metal warehouse, metal’s materiality disrupting the power of n’kondi.Footnote 12

Kaphar stands in a tradition of contemporary artists of African descent who engage the nails and gesture of the minkisi minkondi, working a diasporic ritual aesthetics into pieces displayed in museums. Decades before To Be Sold, Renée Stout created her Fetish 1 and Fetish 2 (Plates 4 and 5), which pierce with nails and hang bundles on the form of an infant and on the artist’s own sculpted body, transforming both into power-figures.Footnote 13 Valerie Maynard’s Mourning for Maurice (Plate 6) used nails to form the hair on a sculpted wooden face, eyes closed, serene and sad.Footnote 14

Plate 4 Side view of Renée Stout. Fetish #1. 1987. Monkey hair, nails, beads, cowrie shells, and coins. 30.8 × 8.89 × 8.57 cm. Dallas Museum of Art 1989.128.

Plate 5 Renée Stout, Fetish # 2, 1988. 64 in. (1 m 62.56 cm). Mixed media. Dallas Museum of Art, Metropolitan Life Foundation Purchase Grant, 1989.27. © Renée Stout, Washington, D.C.

Plate 6 Valerie Maynard. Mourning for Maurice. ca. 1970. Wood and nails. 28 × 20 × 24 in. (71.1 × 50.8 × 61 cm). The Baltimore Museum of Art. Purchase with exchange funds from the Pearlstone Family Fund and partial gift of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., BMA 2020.57.

Kaphar’s work and that of Stout and Maynard form assemblages. Assemblages in archaeology refer to mixed deposits – for example, a broken bowl, an earring, a hair pin, and a gold leaf to cover the mouth of the deceased, found together in a grave. Assemblages in art history usually refer to sculptural mixed-media compositions that juxtapose objects. “Assemblages” in critical theory is a term sometimes used to explain the dynamic and shifting intersectional human.Footnote 15 Feminist and queer theorist Jasbir Puar argues that assemblages even have a political effect of relativizing the human in relation to other circuits of power: “assemblages … de-privilege the human body as a discrete organic thing … We are enmeshed in forces, affects, energies, we are composites of information.”Footnote 16 Puar’s work moves away from the human or human language as the sole sites of meaning-making and as primary sites from which political activity can emerge.Footnote 17

Ancient curses or defixiones also are part of assemblages, although this data – what objects they were found near, the original state of deposit – is often lost to the archaeological record. In a famous example now at the Louvre, a small, unbaked mud figurine pierced with thirteen iron pins, a lead defixio that seeks to compel Ptolemais to love Sarapammon, and a clay vessel were found together.Footnote 18 The assemblage was also thought to include (invisible to us) “forces, affects, energies” (to borrow from Puar) of daimones (spirits); sometimes portions of the assemblage were pinned together with the nail.

Assemblages such as those of Kaphar, Stout, and Maynard share with archaeological, theoretical, and ancient assemblages (the defixio as itself combining elements) the use of nails and the ability to destabilize and lodge critiques of injustice. For that matter, my own book forms an assemblage, seeking to reconfigure the aesthetics of my own field by looking to traditionally marginal aspects of it – curses, and those of low status – and by centering on art as a theoretical frame and conversation partner.

Ancient Mediterranean curses often function within assemblages to insist that an injustice be reversed or a judgment be meted out. We do not know the larger contexts of this sometimes literally underground attempt to gain justice (or what they perceived as justice). Yet, we can think analogously about history and justice in our own times, and how attempts to effect justice or reparations are often foiled by injustice meted out by official judicial systems or by an unwillingness to be responsible to – not guilty for, but responsible to – historical injustices and their ongoing effects. Titus Kaphar’s art, in To Be Sold and elsewhere, engages historical materials in order to respond to state-sponsored (in)justice.Footnote 19 This conversation about restorative or reparative justice occurs as well in legal circles and political philosophy. Adriaan Lanni writes about the possibility that restorative justice could be instantiated to reduce mass incarceration and as an alternative, sometimes, to a criminal legal system that, at least in the United States, is recognized “as racially discriminatory, overly punitive, and ineffective.”Footnote 20 Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow argues that the U.S. criminal justice system is a new “racial caste system,” which perpetuates racial exclusion.Footnote 21 Alexander contrasts the criminal justice system with ideas of social justice. Legal experiments with alternative systems of justice administering can also be found in the work of restorative justice leader Howard Zehr, who argues that the American justice system confuses punishment and justice, using a framework of “adversarial justice”Footnote 22 in which crime is defined as an offense against the state, not against an individual.Footnote 23 Alexander, Lanni, and Zehr adduce multiple and more and less institutionalized forms of justice in the twentieth- and twenty-first-century United States: retributive justice and criminal legal system, social justice, reconciliation, restorative justice.

So too we can think of multiple sites of justice in antiquity. The larger discourse of justice is found not only in elite authors who have time or leisure (scholē in Greek, schola in Latin, from which we derive our words school and scholar) to talk about justice, but also in modes and places like novels or imperial responses on papyrus nailed to walls, or ancient Christian apologiai or defences or other literary texts that depict concerns over justiceFootnote 24 – or in curse tablets that engage in contemporaneous legal work, broadly understood. This larger discourse of justice could be found, for example, in the classroom where the curriculum included student debate of imaginary laws, as if before a judge.Footnote 25 To emphasize: The ancient courtroom should not be the only or primary site for our historical search for evidence of justice-making.

Practices of formal written petitions to the imperial family, of speeches addressed to the imperial family like Justin’s Apologies, which we shall address later, and of cursing are usually set in separate scholarly bins. Written petitions are a topic of expertise by one person interested in archaeology and epigraphy and papyrological evidence and Roman legal history; apologiai or defences are claimed as the scholarly territory of ancient Christianity; curses are the purview of experts studying ancient magic. Yet these practices engage in similar operations of rhetoric of persuasion, proceeding from common sets of assumptions about the nature of the gods, the operation of power, and the right to justice. Various concurrent mechanisms of justice-making, whether sanctioned by the Roman Empire, the local civic authorities, or grassroots, existed and sometimes conflicted.Footnote 26 They deploy different aesthetics – the beauty of a speech, the force of collated documents, the ritual sinking of a curse down a shaft – to do so. Sometimes they envision a divine judge.

The curse is not an atavistic or desperate attempt, compared to a clean and straightforward legal petition or a lofty elite(ish) treatise. All are fuelled by concerns about justice. They produce their attempts to right (what they perceive are) unjust situations within an expanding Roman imperial power, for which, as Brent Shaw puts it, “the experience of witnessing and participating in a trial was arguably the quintessential civic experience of the state.”Footnote 27 This fearsome experience was not confined to the courtroom, or limited to legal cases, or constrained to the imperial center of Rome; the law of the Roman Empire came to have a great and complex impact upon the provinces. The courts were a place for Roman provincial elites to advance their careers; for others, they could be sites of fear.Footnote 28 Provincial elites generally wanted to avoid legal procedures that involved Roman imperial power; reaching out to Rome would give the impression that the longstanding mechanisms of power within the polis were inadequate and would possibly open the door to violence: provincial elites preferred negotiation among the injured parties.Footnote 29 As Shaw emphasizes, the “rituals and frightening apparatus of the court and public punishment” had their powerful effects, emerging even in dreams and nightmares, into a “social field of rule-driven behavior.” Among other strategies of seeking justice, this context “necessitated … curse tablets.”Footnote 30

A Curse from Cyprus

So begins a forceful and emotionally de-escalating (“take… passion from the heart”) sixty-line defixio from Amathous, Cyprus. I don’t know what this Aristōn had on Sotērianos a.k.a. Limbaros, but it was bad. The vocabulary of the curse, and the existence of other legal curses in the same archaeological context, reveal that Sotērianos seeks to silence Aristōn, his “opponent” (antidikon), in court. He tries to re-route Aristōn’s emotions, so that Aristōn’s anger does not empower the case in court. Sotērianos invokes a panoply of divinities to effect this curse: among others, Pluto, Hekate, Hermes, Kore, the Erinyes, and Iaō (a name frequently associated with the Jewish God).

This lead tablet of ca. 14.7 × 25.9 cm was found rolled from top down, with the writing on the inside. It was nestled among over two hundred lead curse tablets and perhaps thirty selenite curse tablets (a thin, milky shard of gypsum) at the bottom of a shaft in Amathous (Plate 7).Footnote 32 The majority, if not all, involved court disputes and were probably written soon before trial.Footnote 33 This is a cache of curses and ritual objects. It is also an archive of legal documents. Those who have carefully studied the handwriting (paleography), the formulae, the names (onomastics), the systems of carving letters into the lead (epigraphy) conclude that the tablets were written and deposited in a relatively short time frame, probably in the third-century CE.Footnote 34

Plate 7 Selenite (gypsum) tablet inscribed with a curse in alphabetic Greek characters. Cyprus. Length: 13.97 cm, Width: 8.89 cm.

These defixiones were not the products of individual worry and secret anger. While each curse was written for a precise occasion, these problems of justice resounded among multiple people and multiple cases. It seems the ritual practitioners likely used references material for model curses, which they could customize: among the selenite curses at Amathous, there were “at least three templates” and a single template for the lead tablets, which urges chthonic divinities to bind and punish someone.Footnote 35 These legal cases use similar language, inserting different plaintiffs and defendants. They nestle together at the bottom of a shaft, forming an archive that brims with concern, that hopes for the tamping down of wrath (orgē), and that begs for the chill and silence of legal opponents.

The clarity of the letter forms, a tendency to orthography and clear spacing, different handwriting, and the use of templates indicates that these defixiones were produced by multiple ritual specialists, not individual commissioners.Footnote 36 We do not know who these ritual experts were. They were likely temple affiliates, perhaps even priests, and their work was professional, ritual, and scribal.Footnote 37 Temple attendants and priests were ritual specialists who sometimes offered one-on-one moments to address the specific needs of worshippers, for example the priests who translated the utterances of the Pythian prophetess at Delphi, the priest-healers of the Sanctuary of Asklepios at Pergamon as recounted in Aelius Aristides’s Sacred Tales, or the ritual practitioner who thumbed a tiny codex called the Gospel of the Lots of Mary to find some oracle for the inquirer.Footnote 38 By the time of the so-called Council of Laodikeia (363–64), Christian priests were banned from work as diviners, indicating the close relations between the tasks of ritual specialists and hinting that some ritual experts critiqued other ritual experts as problematically moonlighting for extra cash.Footnote 39 In the case of Christian divination or amuletic inscriptions, or in the case of Sotērianos’s curse against Aristōn at Amathous, practitioners were acting theologically, which in this instance involved helping to send Aristōn and his son to the doorkeeper and the gatekeeper of Hades. These ritual specialists were interwoven into a larger network of simultaneously cultic and legal expertise.Footnote 40

Amathous provides an exceptionally rich cache of courtroom-oriented ritual objects/texts. Yet the phenomenon of legal curses is empire-wide and temporally broad. One of the earliest publications of defixiones, A. Audollent’s Defixionum Tabellae, offers a taxonomy that includes Iudicariae et in inimicos conscriptae, “judicial and written against enemies.”Footnote 41 In his 1992 book, Curse Tablets and Binding Spells, John Gager includes curses from the classical period in Athens in chapters titled “Tongue-Tied in Court: Legal and Political Disputes” and “Pleas for Justice and Revenge.” Similarly, in the 1990s, Henk S. Versnel made the important argument that we should understand some curse tablets to be “prayers for justice,” and this categorization has since been widely adopted.Footnote 42 The pity is that the power of Versnel’s insight has led to a rigid scholarly categorization: Is this a prayer for justice, or is it a form of vicious and vengeful magic?Footnote 43 This problematic dualism subtly reinforces the good religion/bad magic binary of earlier scholarship, and occludes our understanding the fact that a variety of curses function as legal documents.

The Amathous curses, including Sotērianos’s, are unusual in offering the names of petitioner and accursed. Curses usually mention only the latter, while the petitioner remains anonymous, perhaps seeking plausible deniability. The mentioning of both may enforce the legal quality of the curse, inscribing the defendant and the accused as one might find in a court document above ground.Footnote 44 Sotērianos’s justice-seeking is laced with legal terms. For example, dry, bureaucratic terminology is evoked in the word “the aforementioned” or “previously written” (progegrammenon), which evokes epigraphic practices of setting forth of public notices or even someone’s registration for judgment or condemnation.Footnote 45

Demones (a variant spelling of daimones) are invoked as the first word of the Amathous curse. The term daimōn is usually understood, as with the English demon, to be a negative force. In the texts we encounter in this chapter, daimones are involved in enacting torture and Justin sees them as continually deceptive and evil. Yet elsewhere they are understood as positive, animating forces.Footnote 46 In this Amathousian curse, daimones or spirits are addressed by location, ontology, and bodily orientation: under the earth; whoever they may be; they are lying and sitting. They are identified in kinship terms: fathers of fathers, and also “mothers who combat men,” an epithet of the Amazons used in the Iliad, raising the image of warrior mothers.Footnote 47 The phrase “grievous passion” (thumon… polukēdea) evokes Homeric terminology, and my translation cannot capture the richness of the word thumos, which in Homeric epic marks not simply emotion but a quasi-physical site of courage and anger within a person. The defixio sounded impressive and drew on prestigious, authoritative tradition. Its first four lines comprise an invocation, in (rough) dactylic hexameter with metrical and lexical allusions to Homer,Footnote 48 in the midst of the larger cultural turn of the so-called Second Sophistic, which revisited ancient poets for instrumental means and sought to recover the purer outlook on the world held by earlier humans.Footnote 49 The curse draws on pre-classical traditions that “curative and protective incantations were performed primarily in dactylic hexameters and that they were deemed especially effective in curing anger and other forms of malaise.”Footnote 50 This poetics, found also in other defixiones at the same site, hints at the intoning aloud of ritual speech.Footnote 51

The curse understands daimones to have the ability to regulate the passions or emotions, to take away grievous emotion or thumos. This role sets up the curse’s first imperative demand: “Take over the thumos of Aristōn which he has toward me, Sotērianos, also called Limbaros, and his anger.”Footnote 52 The daimones are called upon to chill (psychron, used twice in rapid succession) the opponents or to make them cold. This language of coldness has aesthetic overtones, both in terms of sense perception and beauty. It signals the sensory experience of coldness and its attendant tamping down of emotion. (Without suggesting that this coldness of rhetoric is universal and transtemporal, I still think of the American colloquial: “Chill, man!”) “Chill” can also denote aesthetic failure in rhetoric or composition, an idea that can extend to failure in courtroom speech.Footnote 53

The curse continues, and despite the possible dangers of intoning ritual texts, I recommend that you read it out loud:

After the use of a standard phrase “I invoke,”Footnote 56 the defixio takes flight into phrases in known Greek letters but with unknown meaning, an effervescence of tongues. Within the to-us-meaningless phrasings we can hear poetic echoes: the repeated rolling-around-in-the-mouth sound of alar… ralar… a[lar]… alar (lines 13–14), the owl-in-the-night sound of akou… akou… akou… akouesthe (“hear, hear, hear, hear,” lines 12 and 13). The ritual object also uses unusual and technical words. Rhēsichthōn, “bursting forth from the earth,” is not everyday parlance, for example, but a term known from other curses and scripts for ritual objects.Footnote 57 The word philaesōsi, left untranslated or as a vox magica by editors, must have been experienced in the ear as a mix of the terms for love or friendship (philos, philia) and salvation or healing (sōsō).Footnote 58 The names of deities also buzz or elongate with vowels: Sisochōr and Adōneia (line 14).Footnote 59 The theological universe not only sounds broad but is geographically broad: among the voces magicae are the names of gods of the Egyptians and the god of the Hebrews.

The legal procedure of consigning someone to a justice system, including for testimony under torture, is evoked with the term paradote.Footnote 60 Aristōn and his son are handed over to the doorkeeper in Hades, the gatekeeper of Hades, and the keeper of the doorbolts or bars of heaven, who is then named (it seems) and given a chthonic epithet. The language of doors and bars may evoke imprisonment. Even the well-placed and well-educated – we shall soon see an example from Epictetus – directly and with emotion-filled vocabulary discuss law cases and hint at the threat of jailing.Footnote 61 We can wonder whether Sotērianos is concerned precisely because he is not elite and cannot buy or benefact or shoulder-rub his way out of the lawsuit.Footnote 62

After this crescendo of language and tumble of letters, the defendant once more seeks justice by means of daimonic regulation of emotion. The terms thumos and orgē are paired again: “chthonic gods, take over from Aristōn and his son the thumos and the anger they hold toward Sotērianos also known as Limbaros.” Ultimately, the curse names what it is: a muzzling spell, a phimōtikon.Footnote 63

This muzzle is to be placed not only on Aristōn, but also on the daimones who are commanded to act but are unable to speak. The defixio continues:

In this portion of the ritual text, the aistheseis or sense perceptions of the daimones are front and center: they cannot speak but can hear. Not only the tongue but also the voice(s) (phōnas) or speech of Aristōn is to be muzzled by the theological forces of underworldly and lower than underworldly beings. The curse is additive: where before Aristōn’s thumos and anger were named (line 17; see also lines 4, 7), here too his glōssa or tongue is “put to sleep” in any “matter” or pragma, a term that refers to business or legal transactions.

The last lines of the tablet crescendo with invocations (thrice “I invoke you”) and commands (five times):

The text ends with four lines which seem to be a hybrid between voces magicae and charaktēres. Presumably the literate gods and daimones can make sense of these forms of writing. I do not say this lightly; the literacy of divinities and daimones is significant to their accessing and effecting these legal documents. Human communication and even conviviality with other sorts of beings is assumed.Footnote 67

Not only the content of the curse, but also its archaeological context, gives data about documentary practices and searching for justice in antiquity. Our knowledge of the archaeological context is admittedly limited, derived from late nineteenth-century letters that describe what local villagers say about how they found the tablets. A letter from 1892 speaks of

the discovery, made by some villagers in clearing what seemed to be a large disused well. They first found a quantity of squared stones, and then rubble, under which was a great quantity of human bones, among which were some gold earrings. In the lower stratum of the bones, they first found pieces of the lead, and subsequently pieces of the inscribed talc, some pieces of which were attached to the side of the well imbedded in gypsum. Later on, they came to water, at about 40 ft. from the surface.Footnote 68

Perhaps the shaft at Amathous was a well.Footnote 69 As we shall find in the next chapter, four curses were sunk into a well in the House of the Calendar in Antioch, with that watery drop-site a key to the purpose of one of the curses.

Perhaps the shaft was a grave. The area where the curses were found is a necropolis.Footnote 70 Many curses are known to have been deposited at graves or associated with the dead, either from archaeological evidence of their find sites or from mention of a nekudaimōn or corpse daimōn.Footnote 71 These deposits in a well or grave may be fueled by an underlying logic of depositing one’s curse at an entrance to the underworld.Footnote 72

And what about all those bones? Andrew Wilburn argues that they are a later deposit, perhaps associated with a plague or catastrophe after the deposition of the curses. Riccardo Vecchiato states, however, that the bones along with the content of the curses indicate a mass grave: the poluandrion mentioned in the curse. This mass grave would include those who have been beheaded and crucified, the latter the ultimate punishment for those of lower status deemed criminals or troublemakers to Roman imperial power.Footnote 73 Vecchiato bases his argument on a fragmentary curse tablet (Audollent 27, IKourion 132) from Amathous, which is directed against at least ten legal opponents (antidikoi), including Metrodoros a.k.a. Asbolios, a banker. This curse too seems to be a silencing spell (phimōtikon) as it asks that the “voice” of certain opponents be taken away.Footnote 74 Vecchiato reconstructs the curse as “demons of the mass grave (poluandrioi), beheaded and crucified” (line 17).Footnote 75 He convincingly argues that poluandrioi does not denote the state of being simply buried but should be translated “those in a mass grave.” In Josephus’s Jewish War (Bell. Iud. 5.1.19), for example, the term arises in a discussion of mass killings during civil conflict in Jerusalem at the time of Titus; the temple had become “a grave for the bodies of household members, making the sanctuary into a mass grave (poluandrion) of civil war.”Footnote 76 Vecchiato’s reconstruction and translation of “crucified,” while possible, is admittedly a guess: only the first four letters of the word are visible.Footnote 77 The term pepelekismenoi, “those who have been cut by an axe,” appears in full; it is an expression usually denoting decapitation. It is used, for example, in the late first-century Apocalypse of John, which refers both to decapitation and to a witness in a court (martyr): the prophet John sees “the souls of those beheaded on account of the testimony regarding Jesus and on account of the word of God” (Rev. 20:4).Footnote 78

Of the legible and published curse tablets from Amathous, thirteen share formulae, among these the Sotērianos inscription of our focus. All thirteen mention their own location of deposit as a much-lamented tomb (pandakrutos). These curses refer to violent and untimely deaths (biaiothanatoi and aōroi), an element so frequent in curse tablets that scholars have often ignored how shocking it is. Thinking that “magic” would of course involve the weird, we have failed to explore the ancillary social and political conditions to these deaths.Footnote 79 Why violent and untimely? Are these violent and untimely deaths effected by private, random means or state-sponsored conditions? We are perhaps desensitized to untimely and violent deaths, and their gendered, economic, status, and racial drivers. With these curses, we can wonder: How are memories of those unjustly dead mobilized? Do their unjust deaths become the material from which justice can be activated? How are, or are, their energies thought to be still present? In the case of Amathous, it maybe that the unjustly and violently dead are again treated unjustly, manipulated by the cursers and the ritual practitioners there. Vecchiato argues that the shaft at Amathous was the site of the dumping of criminals’ bodies: a mass grave that included the decapitated and the crucified, their rattling bones and spirits activated as components of the justice-technology of the curse tablets deposited there.

Whether the bones laid within the shaft preserved traces that indicate crucifixion or beheading is uncertain. Whether the shaft was a well or a grave evades us. What does seem clear is that it was a place of some terror. Yet, this well or shaft was more than a symbolic gateway to the underworld or a materially effective location, its powers of drowning and chilling the curse tablet transferable to the accursed through the logic of similarity. It was also a site of display. Significantly, one remaining piece of selenite tablet has two small holes approximately 1 cm apart on its left upper corner, indicating display (British Museum 1891,0418.59). Handcock’s comments from the late nineteenth century also indicate that some of the selenite tablets were pressed into the gypsum of the shaft wall, and images from the original publication seem to indicate suspension holes for display.Footnote 80 The lead tablets were likely rolled up, some possibly pierced by nails, and perhaps laid into the shaft or affixed to its walls by nails.Footnote 81 This assemblage – the hammering and the nail-piercing – become a more evident act of exposing injustice, when interpretated in light of the practice of nailing and display in Kaphar’s To Be Sold and the exposing of injustice that comes with a nailed proclamations.

We should think of the find site of the defixiones at Amathous as a legal archive. This archive was perhaps deliberately placed in a mass grave that included those violently killed by decollation and crucifixion.Footnote 82 The repetitive aspect of the curses points not only to cultic ritual but also to legal ritual, overseen by a literate expert. The sheer number of defixiones found together recalls a bureaucratic archive.Footnote 83 The very act of depositing one more defixio among so many others – and in the case of some, the act of suspending within or affixing them to the shaft – recalls the public work of legal display, the hanging of documents in antiquity.Footnote 84 Even if the only viewers of a curse placed in a shaft were to be the chthonic divinities and spirits, the social force of the curse resonated above ground as information was passed along informally, through gossip and conversation, and through general knowledge of the practice of making defixiones.Footnote 85 There is a publicness to the display of the Amathous curses.

The curses at Amathous are part of a larger empire-wide seeking of justice by many means. One Amathous curse explicitly indicates resistance to larger political power – or at least someone in political power. A defixio at Amathous takes aim against “Theodoros the governor.”Footnote 86 That curses and resistance to government could be intertwined is well known from elsewhere in the empire. Three curses from Empúries (Ampuria, Hispania) condemn at least three Roman administrators in ca. 75–78 CE.Footnote 87 They also re-orient the world in their very form of writing, as they are inscribed retrograde (from right to left) and from bottom to top. The unusual writing, topsy turvy, does its own work of materializing reversals.Footnote 88 At Mainz, a defixio uses the word adiutor, likely a technical term denoting the adiutor tabulatriorum or assistant of a Roman magistrate.Footnote 89 Tacitus famously tells the story of Germanicus’s death in the early first century CE in Antioch, in the midst of mysterious circumstances (a feud with the province’s governor Gnaeus Calpurius Piso and his wife, Plancina) and ritual foul play: “the remains of human bodies, spells, curses, leaden tablets engraved with the name Germanicus” (Tacitus, Ann., 2.69).Footnote 90 As Wilburn explains,

Magic directed at the state, particularly aggressive magic aimed at harming members of the provincial administration, clearly would have been viewed as an illegal activity, endangering both parties, the practitioners and those who employed them. These proscriptions may suggest that the use of magical acts constituted resistance against Rome in the minds of the authorities.Footnote 91

In addition, the vocabulary of curses and of official petitions overlaps: like combats like. The procedure of hanging and display of historical, documentary evidence includes both imperial petitions, as we shall see below, and curses: a curse is like an imperially posted document addressing situations of injustice.Footnote 92

Curses are mechanisms for producing otherwise possibilities against imperial bureaucracy and injustice, effected by calling upon various beings, whether daimones or god(s).Footnote 93 They are tools against exercises of power that could provoke fear. Roman legal procedure could transform defendants, draping their bodies with the emotional manifestations of shame and penitence.Footnote 94 The emotions (pathē, things you suffered or experienced), were politically useful tools. Francisco Marco Simón argues regarding some judicial defixiones that “[t]he practice clearly shows the emotional – or not strictly legal – dimension of lawsuits, which were of course heard in public, in some cases at least before a large audience.”Footnote 95 To resist the emotions’ or passions’ ability to render one passive, suffering from external stimuli, one needed management strategies, tools that are simultaneously philosophical and theological.

Stoics created a taxonomy of the emotions – a kind of psychic and community map that allows for people, mostly elite males concerned with self-mastery,Footnote 96 to find their way out of the confusion of having wrong opinions (doxai) about the circumstances that surround them. Cicero, while not himself a Stoic, sympathetically (!) outlines in his Tusculan disputations a classic Stoic response to the pathē or the emotions and summarizes: “Philosophy, in removing distress as a whole, also removes whatever errors may trouble us on any particular point: the bite of poverty; the sting of public disgrace, the darkness of exile; or the other things I have named” (Tusc. disp. 3.82). He offers a list of what falls under the genus of aegritudino: envy, rivalry, jealousy, pity, anxiety, grief, sorrow, weariness, mourning, worry, anguish, sadness, affliction, despair (Tusc. disp. 3.83).Footnote 97

Curses emerge among other techniques to master emotions in antiquity. Defixiones are one among many technologies and therapies (therapeiai) to regulate the self and to regulate the self in community – that is, not only to master the desire (epithumia) or fear (phobia) within, but also to control the circulation of emotions without. An extensive set of therapies could be found in philosophical practices of regulating delight, desire, distress, and fear.Footnote 98 This circulation of the pathē or emotions is fundamentally political, as a theoretical framework derived from contemporary queer theory helps us to see. In The Cultural Politics of Emotion, Sara Ahmed writes, “Feminist and queer scholars have shown us that emotions ‘matter’ for politics; emotions show us how power shapes the very surface of bodies as well as worlds. So in a way, we do ‘feel our way’. This analysis of how we ‘feel our way’ approaches emotion as a form of cultural politics or world making.”Footnote 99 Ahmed continues her diagnosis: “[F]ear works to restrict some bodies through the movement or expansion of others. Within feminist approaches the question of fear is shown to be structural and mediated, rather than an immediate bodily response to an objective danger.”Footnote 100 That is, fear is the product of threats that are themselves produced through narratives of who is to be feared. Fears are conjured by the fearful work of daimones in curse tablets; narratives of Christian apologists like Justin, as we shall see, both reflect and produce fear. Ahmed gives the example of political discourse in the United Kingdom about “bogus asylum seekers” and the importance of the nation resisting a “soft touch.” We could easily adduce examples of emotional-political strategies in the United States to stoke fear against immigrants “taking our jobs” or bringing disease or overrunning national boundaries – these racialized and political narratives stoke fear and disgust, and produce concrete effects like placing the children of border-crossers in cages.Footnote 101

Curses are one strategy amid the search for justice and the circulation of emotion in antiquity. Roman law and Roman systems of pleading an injustice to the emperors are visible in the official legal documents. But as Ari Bryen, Jill Harries, and Jeremy Williams have shown, legal discourse also appears in other sorts of texts, including novels or romances.Footnote 102 The writings of a Christian apologist like Justin, alongside early Christian martyrdoms, are part of this literature. These philosophical-theological discourses in antiquity reveal concerns about managing the pathē or emotions in the face of injustice and sometimes, more specifically, in the face of legal cases. From the conflict-laden Roman republican period of Cicero to the dangerous Roman imperial period of Epictetus and far beyond, people debated how to cope with fear of unjust power and how to enact justice. Some, particularly elite males, used strategies of philosophical dialogues to cope with political fear and the circulation of emotion. They asked: Were the emotions (pathē) epistemologically misleading or useful? Did they distract a person from strength or excellence (the Latin virtus, which contains the word for man, vir) and courage (the Greek andreia, which does the same, anēr), terms coded as elite and masculine? Others used curses to cope with these fears regarding legal power. Some likely used both.

The popular philosophical writings of Epictetus reveal that emotions could be dangerously stimulated by political fear:

But what says Zeus? “Epictetus, … since I could not give you this [complete freedom], we have given you some part of ourself, this faculty of choice and refusal, of desire and aversion… ; if you care for this and place all that you have within it, you’ll never be thwarted, never hampered, won’t groan, won’t blame, won’t flatter anyone.” …

Now, Epictetus pictures a threatening dialogue:

[Character 1] But I will bind you.

[Character 2] Dude, what are you saying? Bind me? My leg you will fetter, but my moral choice not even Zeus himself has power to overcome.

[Character 2] Only my paltry body.

[Character 1] I will behead you.

[Character 2] Well, when did I ever tell you that mine was the only neck that could not be severed?

[Epictetus’s summary] These are the lessons that philosophers ought to rehearse, these they ought to write down daily, in these they ought to exercise themselves.

Note here the language of binding. In some ways it is not surprising that the semantic field for katadesmoi, binding spells, overlaps with terminology of punishment and imprisonment in the Roman Empire.Footnote 104 Yet its resonance is also striking, reminding us that the language of binding marks power and force. Justin, too, uses the imagery of binding and chains in his sly critique of the Roman imperial family and his complaint that they persecute Christians based on the name alone. He does so in his comment that some “condemn themselves so as to need no other judges, when they sentence us to death or chains [bindings, desma] or some other such penalty for having done these things” (1Apol. 69.2).Footnote 105

Fear was not the only dangerous emotion in circulation. Rivalry, according to Cicero, is a form of distress; envy, according to the physician Galen, is the worst form of grief. These are the sorts of emotions that could produce the conditions of conflict that blossom into a lawsuit. Galen, in a treatise on The Diagnosis and Cure of the Soul’s Passions, pinpoints envy and grief as disease or emotion: “And what must I say of envy? It is the worst of evils… All grief is a disease (pathos), and envy is the worst grief” (Aff. dig. 35).Footnote 106 Envy, according to the second-century CE rhetor Apuleius, can even produce legal trouble. In his Apologia or defence against the accusation of magic, Apuleius says: “For no reason other than baseless envy can be found for concocting this lawsuit against me and the many dangers to my life that preceded it.”Footnote 107

The philosopher must work hard, cultivating an askēsis or a discipline, to inure himself (masculine used deliberately) against political power, even political power manifest in bodily control and harm, as the short passage from Epictetus shows.Footnote 108 Epictetus’s speeches are not personal, individualized musings on how to be a better person. Elite men spent hours discussing the management, moderation, and extirpation of the passions or emotions, with particular focus on how those of lesser status – children, the enslaved – could often provoke anger. Moreover, while being a philosopher could be a posh business, as one received salaries from elite students and even imperial attention and imperially sponsored positions or “chairs,” it could also be a dangerous, stomach-turning business. Seneca’s political philosophy led to his death. Philosophers and theologians who felt that danger addressed it in their dialogues and writings. These writings iteratively, in the back and forth of the dialogic form, worked out the conceptual bases for addressing and offering a therapeia for the real political and social fear around them. These are works of practical philosophy, even of practical theology. Their very form as dialogues shows their literary conceit as a community project: their dialogic nature maps intrapersonal development of skills of resistance – a verbal martial arts sparring ring. Epictetus’s Dissertations even represent a larger community in that they are the notes, it seems, of his student Arrian.

The philosophical texts we read can be seen as practice for future encounters with or stimulations of emotions, practice scripts aimed against external impressions that can mislead, and desire and aversion that can hinder.Footnote 109 Defixiones do different work and likely often emerge from those of lower status. They nonetheless are technologies to cope with similar problems: how to manage in the face of judicial danger, how gods and other non-human beings might be present and engaged, and how to navigate toward what one perceives to be a just outcome, or safe harbor. These emotions should be seen not only or primarily as a private issue but also as a larger, public phenomenon. A curse that indicates annoyance on the part of Aristōn against Sotērianos or, as we’ll see in the next chapter, a tiff between the greengrocer Babylas and the commissioner of the spell against him, discloses not just private anger (“Let me win my lawsuit!”), but also the kind of public emotion that produces multiple curses against Roman officials in the region of Spain in the first century CE. Sotērianos sought to ensure the outcome of his case by silencing his opponent and by whirling up daimones and divinities onto his side of the legal battle. This muzzling also functions to quell thumos and orgē; it is a bar against emotions.

Creating Legal Archives: Justin’s Apologies and Imperial Rescripts

Enter, in philosophical robes (Dial. Tryph. 1.1), Justin Martyr, a cosmopolitan man born in Flavia Neapolis (modern-day Nablus in Syria Palestine) and dweller in Rome, where he fought with the philosopher Crescens. These are facts that he announces at the beginning of his Apologies, as he introduces himself as a colonial subject to the emperors.Footnote 110 As a provincial communicating with the imperial family at the level of petitions and at the level of contributing to Roman legal thought, Justin is not unique. The famed Roman legal thinker of the early third century CE, Ulpian, also writes “as a Roman lawyer, as a communicator with Greeks and as the native of a city with a ‘provincial’ identity containing both Greek and residual Phoenician elements,” as Jill Harries puts it.Footnote 111 Indeed, Ulpian can even be seen as a generation-later rival to the likes of Justin, since he was rumored to have guided provincial governors by listing rescripts directed against Christians.Footnote 112

Justin writes in the shadow cast by brutal Roman quelling of Jewish resistance in 66–73 in Palestine, in 115–17 in Cyrenaica, Egypt, and Rome, and in 132–35 in the Bar Kochba revolt in Jerusalem.Footnote 113 He writes at a time when Christ-followers were sometimes perceived as an aberration from or a heresy of Judaism, and Justin himself seems to be an early “inventor of heresy,”Footnote 114 seeking to construct his form of Christianness by excluding other contemporaneous Christian and Jewish communities. In part because of the philosophical and culturally sophisticated tone Justin assumes, scholars have moved from interpreting him as (solely) an early Christian theologian to seeing him as one voice among many in the so-called Second Sophistic.Footnote 115 He engages in broad cultural practices of discussing justice, engaging philosophical ideals, and performing as a rhetor – even if he does so by using the Jewish scriptures and the story of a crucified anointed one.

Justin’s Apologies, written ca. 150–55 CE, inscribe as addressees the imperial family members Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius, Lucius Verus, and the Sacred Senate and Roman people. Justin uses the epithets of Roman emperors to question who they are: epithets of “piety” (eusebeia in Greek, pius in Latin, applied to Antoninus Pius) and “philosophy” or “philosophical” (applied to Marcus Aurelius). He also refers to Lucius as both philosopher and “lover of paideia.”Footnote 116 Just the role of emperor and that of philosopher blur in Justin’s writing and in imperial self-presentation, so too Justin constructs himself variously as rhetor, philosopher-theologian, and legal advocate.Footnote 117

Justin’s appeal to the emperors not only mentions documentary exchanges, but also participates in the documentary conventions of the time, appealing to Roman bureaucratic systems of adjudicating petitions. The conclusion to what is conventionally called the First Apology states:

And although, on the basis of a letter of the very great and very renowned Caesar Hadrian, your father, we are able to insist that you command that judgments be given in accordance with our petition, instead we have petitioned not on the basis that this decision was made by Hadrian – but we have made this address and exposition on the basis of our knowing that our petition is just. And we have attached a copy of the letter of Hadrian, in order that you might know that we are telling the truth in this manner also. And this is the copy (to antigraphon).

The word antigraphon can refer to a copy of an official document, and Justin’s text goes on to cite a letter of the emperor Hadrian. This is not particularly exciting stuff: it is a bureaucratic gesture toward a bureaucratic document. But that gesture in itself is interesting. Justin adduces an assemblage and shows himself conversant with legal archival practices; he asserts the worth of his own document, with its appended evidence, within these protocols.

Justin offers an imperial letter as a rescript that responded to Christian complaints. Scholars of ancient Christianity have understood that there was an established procedure for petition of the emperors (libelli) and receipt of response (subscriptiones), but generally have engaged in a fruitless debate of asking whether Justin’s document is real: if this rescript is genuine, it indicates that the Roman imperial family was aware of Christians and responded to concerns about them. Absent further documentary evidence, we cannot know more about this situation. What we can know is that Justin’s adducing of an antigraphon indicates his performance of participation in a larger system. It is evidence of his competencies to navigate documentary exchange. He leans into contemporary practices of legal assemblage in order to argue his case. These practices are well known from petitions to the emperors and responses, a phenomenon revealed in epigraphic evidence and other texts that offer official complaints about governmental abuses.Footnote 119

We cannot know how or if Justin’s documentary assemblage and display originally worked. We have no autograph with appended documents. The primary manuscript of Justin’s mid-second-century Apologies is found in the fourteenth-century Parisinus graecus 450.Footnote 120 Yet even this late manuscript, along with evidence within Eusebius’s Ecclesiastical History, points to a constellation of texts around Justin’s Apologies, including a rescript of the emperor Hadrian and one (or two) imperial letter(s).Footnote 121 These rescripts and letters reveal social discourses regarding law. That is, as Roman legal historian Ari Bryen has argued, the history of power, force, justice, and debate can be found not only in documents we adjudge to be bona fide legal transcripts, or petitions and responses, but also in how these are discursively represented in non-legal texts.Footnote 122

A close look into the Apologies reveals even more assertions of documentary evidence and exchange. Justin refers the emperors twice to acta or legal documents by Pontius Pilate (1Apol. 35.9, 48.3).Footnote 123 He mentions “these things we have submitted to your inspection” (1Apol. 67.8), referring, it seems, to teachings of Jesus as documentary evidence. And Justin himself demands the physical display of documents: “And therefore we ask you to add the subscription which seems good to you to this petition and to post it up” (Justin 2Apol. 14.1 or 1Apol. 69.1).Footnote 124

Justin asks to participate in a culture of documentary bureaucracy and assemblage. He does so amid a larger socio-political context of “interminable embassies from cities, mainly Greek,” as well as retinues of bureaucrats that travelled with the emperors, even on military campaigns, and rich evidence from Egypt reveals the drone of quotidian petitions.Footnote 125 There was an aesthetics of display involved in these procedures. Tor Hauken and others have reconstructed the likely process: “petitions were handed in by petitioners or the representatives in person at the emperor’s residence; with or without the instructions of the emperor, the secretary a libellis prepared and signed an answer which was written underneath the petition on the same sheet, and in turn approved by the signature of the emperor.”Footnote 126 From the time period of Hadrian to Diocletian, the use of petitions was strictly formalized, involving a libellus and a subscriptio. Sometimes, instead of a rescript, one found an epistula (Latin) or gramma (Greek).Footnote 127 The answered petition was joined in a volume with other petitions and displayed at an established location. The Temple of Apollo and the portico of the Baths of Trajan in Rome were two such locations. A (putative) letter of Marcus Aurelius to the Senate about the Christians, which follows Justin’s Apologies in Parisinus gr. 450, states that the information within the letter should be posted in the Forum of Trajan. The documents would then be sent to the imperial archive.Footnote 128

We should picture documents displayed in stone in the cities of the Roman Empire, and also nailed up in key locations of deposit – hung, affixed. The defixiones of Amathous, some suspended in a shaft, echo this procedure. The assemblage of historical documents and nails in Kaphar’s To Be Sold allow us to see more clearly how a recent assemblage addresses larger questions of (in)justice; used as a theoretical framework, it allows us to ask whether and how such nails and affixing of documents served purposes of justice in antiquity, as well.

Justin, Demons, Justice

The echoes between Justin’s writing and the rolled lead tablets and the selenite curses with their light, mineral moonglow are not limited to formal documentary procedures of demanding justice and of hanging or announcing the responses to requests for justice. Justin’s appeal to the emperors also indicates concerns about daimones and magic; daimones, as we recall from Sotērianos’s curse, can help to effect (what is perceived as) justice.

Daimones, for Justin, are engines of deceit. They learn about the future coming of the Christ, the anointed one, and proleptically lard into human history myths and practices to make it seem that the message of Christ is secondary. Daimones engage in the work of deceitful imitation or mimesis (e.g., 1Apol. 62.2; 64.1). Dionysus, the godly son of Zeus who is ripped and torn and is “taken up into the heavens” (1Apol. 23.3, 54.6) makes Christ look like a copyright infringer. Daimones heard about Moses taking off his shoes before the divine and instituted similar rites in their most sacred places (1Apol. 62.2). Daimones knew of the stories of creation from Moses and invented the births of Kore and Athena as imitations (1Apol. 64.1-5). Sneaky, powerful daimones.

Justin’s very active daimones not only imitatively and maliciously fold time, making Christ’s deeds and followers’ rituals look derivative of non-Christian worship, but they also produce magic. Justin famously refers to “Simon, a certain Samaritan… who… through the art of the demons who moved him, performed magical deeds in your royal city of Rome, who was thought to be a god and was honoured as a god by you with a statue” (1Apol. 26.2; cf. 1Apol. 56.1–2, 2Apol. 15.1).Footnote 129 Justin also refers to one of Simon’s students, Menander, who performs magical art (technē) in Antioch (1Apol. 26.4). And Justin associates his own community not with invoking (the horkizō used several times by Sotērianos in his curse) but with revoking or exorcising (eporkizontes, translated in terminology of exorcism):

For throughout the whole world and in your own city many of us … exorcised many who were possessed by demons in the name of Jesus Christ who was crucified under Pontius Pilate. And they healed them, though they had not been healed by all the others – exorcists and those who incant and potion-workers. And still they heal, breaking the power of the demons and chasing them away from human beings who were possessed by them.

Here Justin not only puns on the term “revoke” (horkizō) used in many defixiones, but also displays a vocabulary of ritual practitioners: exorcists and healers and potion-workers (those who trade in pharmaka, poisons or medicines).Footnote 131

Justin’s Apology is deeply concerned about the activity of daimones in a world thick with spirits, air and earth clogged with various kinds of beings. The theology of such a complex ontology – of beings that do not neatly align themselves into humans or gods or heroes – should be understood not only in light of Jewish apocalyptic thought, but also in relation to concerns about rerouting justice through practices of defixio-making. Daimones, among other beings, motor these ritual objects and rituals; on this, the curses and Justin Martyr agree.Footnote 132 The term daimōn in the unpublished index to Karl Preisendanz’s Papyri Graecae Magicae takes up approximately two columns of entries. These daimones are not solely detrimental. We find recipes that both invoke and push away daimones, including a rite for acquiring an assistant daimōn (PGM I.42) and a phylactery against a daimōn (PGM IV.86–87).

Daimones operate in Justin’s realm and in the realm of curses; so too legal terminology. Justin’s Apology heats up considerably from the fairly polite, if snide, introduction in which he addresses members of the imperial family and calls upon them to be what they claim to be: just, pious, influenced by paideia (education, culture) and philosophy. The text mimics larger judicial processes of petition and response, and does so in a style – as Ari Bryen has put it, an “aesthetics of justice”Footnote 133 – rooted not only in Justin’s self-presentation as a philosophical man, but also in the varied quotations and dramatic prose that constitute his rhetoric. The heating up of his prose is quite literal. Justin moves from calling upon the imperial family to “have prudent discernment along with kingly power” to the statement that “we believe and have been convinced that each of you will pay penalties in eternal fire according to the worth of his actions” (1Apol. 17.4).Footnote 134 The “you” is not directly or immediately the emperors, but given that they are the addressees at the start, they would be understood as the targets of eternal fire. (Justin himself accuses the emperors of listening to magoi [1Apol 18.3-6].)Footnote 135 This language of punishment and penalty should be understood within the wider judicial procedures – sometimes felt as violence, sometimes the cause of nightmares, as Shaw reminds us, sometimes the condition which produced philosophical practices, often the cause of fear.Footnote 136

The themes of judgment of the emperors and others continues: “Consider what happened to each of the kings that have been,” it reads. “They died just like everybody else” (1Apol. 18.1). But, the text implies, such death does not come with anaisthēsia, with a lack of sense perception. If the emperors think they will be just fine after death – punished, but then left to the quiet of oblivion – they are wrong.

For conjurings of the dead – both visions obtained from uncorrupted children, and the summoning of human souls – and those whom magicians call ‘dream-senders’ or ‘attendants’ – and the things done by those who know these things – let these persuade you that even after death souls remain in consciousness – human beings seized and convulsed by the souls of the dead – whom all call demon-possessed and frenzied – and the oracles, as you call them, of Amphilochus and of Dodona and of Pytho, and the other things of that sort.

Justin evokes a larger discourse on the presence and procedures of oracles, both famous (the Pythian) and unremarkable (using children for divination) in antiquity. He points to the continued work of the dead who return to divine for the living. The term daimoniolēptous, “demon-possessed,” occurs in Greek literature only here and in Justin’s 2Apol. 5.6.Footnote 138 But if we extend our range of investigation outside of the normal lexica to so-called magical literature, we discover the creative buzz, clack, and hiss of many daimonic compounds: daimoniazomenos and daimonizomenos, daimoniakon, daimonioplēktos, daimonissai or daimōnissai, daimonotaktas.Footnote 139

Justin participates fully (cultically, semantically) in the daimonic, ritual-filled world of antiquity. He even recognizes the significance of nailing in ritual:

For the daimones we are talking about strive for nothing else than to lead humans away from the God who made them and from his first-begotten Christ. And those who are not able to lift themselves up from the earth, they nailed and continue to nail to earthly and manufactured things, and those who hastened toward the contemplation of divine things they beat back…

It is likely that the living and the dead are both battered by daimones here. The phrase “those who can’t lift themselves from the earth” recalls the earthiness of the Sotērianos inscription, with its concerns for those things under the earth. The passage duplicates the verb for nailing, once representing completed action, and once using the present to intensify the ongoing action: Those who can’t lift themselves from the earth are nailed and continuously nailed to earthly and handmade things. This passage makes little sense unless it is grounded in the rituals of nailing defixiones that we know from Amathous and elsewhere. It recalls also the nailing gesture of minkisi-making as the power figure is activated by the nail or blade penetrating into it. The art of Kaphar, Maynard, and Stout uses nails to produce a critical intervention: to evoke unjust conditions of power and legal action. What Justin sees as an oppressive nailing down, someone like Sotērianos might have seen as a mechanism of the display of injustice, an activism of resistance against a dominant, literally above-ground court system. Justin, in turn, fully above board, imagines his document or biblion nailed alongside imperial documents.

Justin refers to so-called magic, using in-house terminology like nekuomanteia and referring to magoi. But what does this have to do with justice? Justin frames his own argument in terms of punishment for those who live unjustly (hoi adikōs biōsantes): Gehenna: “Do not fear those who kill you and after this are not able to do anything. Fear rather the one who is able after death to send both soul and body to Gehenna (Luke 12:5, cf. Matt. 10:28)” (1Apol. 19.8). This passage in which magic and daimones and punishment arise is part of a larger philosophical discourse about justice and about how God will effect it. Justin addresses the pathos of fear, which arises in the midst of the thrum of possible imperial violence, as Epictetus also evidenced.Footnote 141

Sotērianos’s curse from Amathous was one example from among the many legally focused defixiones from the same shaft. So too we find in Justin’s writings a particular legal case that reminds us of the fearful and complex mechanisms of (in)justice. The case involves a governor named Urbicus and a legal petition brought to the emperor. A woman who has “learned the teachings of Christ” tries to persuade her husband of eternal fire for those who do not live according to right reason. The husband continues in her ways, and the woman refuses sexual relations with him. She seeks a repoudion – that is, a divorce, with the text here providing the technical Latin term in Greek transliteration: “She then submitted a petition (biblidion) to you, the emperor, praying that she be given leave to set her financial affairs in order first and to answer the charge later, after she had arranged her affairs, and this you granted” (2Apol. 2.8).Footnote 142 This case is similar to early Christian stories found in what we call the apocryphal acts, in which a high-born woman who becomes a follower of Christ rejects sexual contact and problems emerge between her and her husband or fiancé, stimulating novelistic violence and even governmental crackdowns. Yet such a case – that of Justin’s high-status woman, sadly unnamed – demonstrates the perils of law suits and the ways in which even legal documents cannot prevent injustice.Footnote 143

Justin’s Apologies take the hybrid oratorical-philosophical-political form of something that claims to be like a libellus or petition. The Apologies evince an aesthetics that is in conversation with the legal assemblages of civic-imperial petition and response or the shaft of curses-as-legal-interventions at Amathous. The Apologies do not mimic the form or genre of the 60-line defixio from Amathous. Yet both Justin and the Amathous curses participate in the juridical archival practices of antiquity: assembling and appending documents. And both Justin and the Amathous documents use daimones to mobilize (what they think is) justice. Justin’s use of daimones and his claims for justice and eternal fire occur in an ontologically abundant world in which spirits, divinities, humans, and objects like curses or rescripts or imperial letters co-participate in effecting justice. Justin’s writings emerge in and refer to a context in which appeals to the emperor were a regular mechanism for curbing abuses. And the cache in Amathous offers its own archive against perceived injustices.

Conclusions

Titus Kaphar nails documentary evidence to a repetition of portraiture. His To Be Sold offers an ethical intervention into history by means of history and by means of nails. He self-consciously participates in a historical and aesthetic tradition. By foregrounding my analysis of the Amathous curses and Justin’s Apology in Kaphar’s work, I do not argue that he – or Stout or Maynard or other contemporary artists – do the same thing as the Kongolese ritual practitioners who produced or used power figures, or the ritual practitioners of antiquity who produced or used defixiones. Moreover, the art works of Kaphar, Stout, and Maynard which make reference to minkisi minkondi share similarities and also inevitably differ from each other, and their use of nails also at times references the nails of the cross or hoodoo practices. Yet, their art is a form of “rhyming” with Kongolese objects, to borrow a word from artist Edward Sorrells-Adewale;Footnote 144 it deliberately and politically draws on the “legacy of the ancestral arts” of Africa.Footnote 145

These contemporary art works provide a space for investigating the aesthetics of the nailed curse tablet and create the grounds for us to ask whether some defixiones, too, engage history, emotions, and justice. Justin’s own libellus or biblidion is legal material and appends legal materials; it works to control capricious and sometimes violent systems of justice. Justin’s own rescript plays with nails, demanding the physical display of documents.Footnote 146

At the beginning of Justin’s Apology, an account of injustice, Justin calls upon the emperors as phylakes dikaiosynēs (1Apol. 2.2), “guardians of justice.” He pleads for legal solutions and for justice, on behalf of a reader – likely not the imperial family, in the end, but fellow Christ-followers. Justin’s text is best understood in relation to and even through other strategies and materializations of seeking justice: appeals and imperial rescripts; defixiones as “prayers for justice”; daimones and divinities as guaranteeing or interrupting justice.

Few scholars of early Christianity or, for that matter, of Roman law have understood curses as justice-seeking mechanisms relevant for understanding ancient Christians’ engagement with Roman imperial judgment. Yet, when we triangulate work like Kaphar’s with the writings of Justice and a curse like that of Sotērianos, we can see that the latter takes part in larger experimental and improvisational attempts at justice: a legal system that runs alongside existing formal procedures of justice-seeking, in the midst of grinding state-sponsored procedures that were often perceived to be unjust. Curses were not only a matter of private anger or revenge, the steam valve of sick or frustrated individuals. They make sense in the context of legal exercises of power and the exchange of documents, and in the midst of philosophical texts of the Roman imperial period which turned to issues of ethics and emotions.

These objects, whether the exemplary defixio from Cyprus or Justin’s Apology, seek justice and gain authority in relation to other documents and the formal procedures of deposit: that is, they are archival practices. Archival practices create assemblages not only to retain information, but also to promulgate an aesthetics of justice. Justin cites imperial documents and forms his own miniature dossier within the Apology; the defixio from Amathous echoes others, indicating the existence of a paradigm, perhaps in book form, and it is laid along with at least 219 other lead defixiones and thirty selenite tablets in a shaft: an odd archive. These objects are theological and concerned with theodicy. They assume that divinities and daimones are interested in and involved in the procedures for seeking justice. This judiciary system, concurrent with and mingling its very vocabulary with state-sponsored legal proceedings, may have been conducted by those of low status or those who perhaps had little or no access to effective representation in court procedures.

I do not want to romanticize early Christians as heroic de-colonialists or resistors of Roman imperial power. No such simple story can be told. But we have seen that Justin suggests that the imperial family will stand for judgment, just as he acknowledges that some currently are unjustly judged according to the name “Christian.”Footnote 147 Some of the tablets from Amathous “bear witness to covert resistance to Roman authority.”Footnote 148 And Justin’s Apologies weave in historical documentation – imperial letters, whether real or invented – to offer a critique of present imperial injustice. Sotērianos’s defixio, or imperial rescripts, or Justin’s libellus are mechanisms to reroute the emotions of litigants and the violence of legal systems. They are interventions into the challenges and means of finding justice in a world buzzing with humans, objects, and daimones.