I. Why It Matters to Remember the War

For almost a decade, from 1542 to 1550, England invaded, occupied and attempted to conquer Scotland. The attempt was finally unsuccessful, but invasive war was always legally and morally dubious, and these campaigns were designed to devastate: they were explicitly punitive, deliberately brutal. The report of the earl of Hertford (later Protector Somerset) to the English privy council on his 1545 border campaign itemises every one of the 287 Scottish monasteries, castles, market towns and villages ‘brent, rased and cast downe’ by his forces in that campaign; in 1544 the citizens of Dunbar, men, women and children, were suffocated and burnt as they slept.Footnote 1 At the Battle of Pinkie in 1547 between six and ten thousand Scots soldiers were slaughtered rather than (as would be usual) some being captured and made prisoners of war.Footnote 2 The economist S. G. Lythe long ago noted the devastation of Scotland’s means of food production in the wake of Hertford’s 1544 and 1545 campaigns, along with the plundering of Tayside and Fife during the occupations of Broughty Craig and Inchcolm in 1547–8.Footnote 3 From Dundee in November 1548, Sir John Brende wrote that there was like to be ‘little doing’ for the English forces that winter in Tayside and Fife, because ‘The country is so wasted there is nothing to destroy.’Footnote 4 But as well as despoiling the means of material sustenance, soldiers attacked the country’s spiritual infrastructure, smashing up the ‘ydols’ of traditional worship and ‘stripp[ing] the Church of much of what had made its piety live’.Footnote 5 The ‘dissolution of the monasteries’ is, to most of us, an episode in the well-known narrative of the formation of English exceptionalism. It has stirred richly expressed feelings about the ambiguous legacy of Henry VIII’s Protestant Reformation, from William Empson’s famous comments on Shakespeare’s ‘bare ruined choirs’ to Eamon Duffy’s evocatively titled The Stripping of the Altars.Footnote 6 The choirs of Scotland’s magnificent abbeys and churches, by contrast, were stripped bare and brought to ruin by looting, killing and cannon-fire inflicted by English forces in 1544 and 1545. Even in Alec Ryrie’s fine, witty analysis, this ‘military iconoclasm’ remains hard to assimilate to a meaningful narrative of Scottish Reformation.Footnote 7

Yet this nine years’ war was almost no less devastating for the English. By the summer of 1549, William Paget was writing to Protector Somerset, begging him to abandon his attempt to conquer Scotland: ‘we are exhausted and worne to the bones with these eight yeres warres both of men money and all other thinges’, he wrote.Footnote 8 In the same year, according to Sir Thomas Smith’s Discourse of the Commonweal of This Realm of England, artificers and merchants were observing that England’s cities, heretofore wealthy, had ‘fallen into great desolation and poverty’, that ‘not only the good townes are sore decayed … but also in the country … there is a such a general dearth of all things’.Footnote 9 Exiled from court in the summer of 1549 precisely for having criticised Somerset’s handling of the economy, Smith wrote the Discourse as his response: a brilliant analysis of the catastrophic effects of wartime currency debasement. ‘For the furniture of his wars’, wrote Smith, the king was continuing to import ‘armor of all kind, artillery, anchors, cables, pitch, tar, iron, steel, handguns, gunpowder’, squeezing his subjects to pay for it, though ‘there is no treasure left within the realm’.Footnote 10 In political terms, the war’s effects were, if possible, even worse. Franco-Scottish victory in 1550 brought about the very situation that the war had been fought to prevent: Mary Stewart’s marriage to Henri II’s son, the Dauphin François, gave the French Crown a claim to the English throne, greatly exacerbating England’s political isolation and vulnerability at the accession of the Protestant Elizabeth in 1558.Footnote 11 Just after the English defeat, in 1550, the English ambassador to France, Sir John Mason, had to watch uncomfortably as Franco-Scots victory was celebrated in King Henri II’s triumphal entry into Rouen. First, images of the Scottish burghs freed from English occupation were paraded – ‘Voilà Dondy, Edimpton, Portugray’ (‘Behold, Dundee, Haddington, Broughty Craig’) – and later on, as part of a magnificent spectacle on the river Seine, Neptune appeared, offering Henri fair winds to conduct his navy up the Thames, to conquer Albion and to become Henry IX of England.Footnote 12

Ultimately, and more importantly, the harsh lessons of the failed 1540s war to conquer Scotland actually shaped the success of Elizabethan England, economically, geopolitically and constitutionally. Sir Thomas Smith and William Cecil, Lord Burghley, chief among the innovative thinkers and political advisors of Elizabeth’s reign, both began their political careers as strategists and propagandists for Somerset’s war in Scotland.Footnote 13 They never abandoned their belief in the desirability of the war’s goal, which was the neutralising of Scotland’s potential as an ally to England’s enemies by the creation of an Anglo-dominated ‘Great Britain’. However, they also fully absorbed and creatively transformed the harsh lesson of the war’s failure as the means to achieve that goal. Joan Thirsk has shown how Smith’s analysis of the war’s economic effects laid the ground for the astonishingly successful development of a consumer society in Elizabethan England, through the encouragement of economic projects.Footnote 14 Jane Dawson likewise demonstrated how central to William Cecil’s vision remained the need to achieve English control over the unification, political and religious, of the British Isles, thus securing the British coastline from the threat of foreign invasion.Footnote 15 And what we now think of as the Elizabethan period’s most important innovation – a legally limited monarchy, famously described by Patrick Collinson as the ‘monarchical republic of Queen Elizabeth I’ – had its origins at least partly in William Cecil’s and Thomas Smith’s archival research on behalf of Somerset’s vision of a united, Protestant Britain in the ‘acephalous conditions’ of Edward VI’s minority.Footnote 16 Tasked to justify England’s historic right to invade Scotland, Smith transformed the old feudal claim into a title based on England’s legal and constitutional superiority within a new, godly ‘British’ imperium. ‘If Smith’s De Republica Anglorum had an intellectual antecedent’, wrote Jonathan McMahon, it was the plan of Protector Somerset’s war propaganda team ‘for “De Republica Britannica”’.Footnote 17 Economically, politically and symbolically, then, what we think of as ‘Elizabethan England’ – a virgin queen ruling a peaceable and prosperous island nation, just beginning to be a maritime trading and colonial power – represents, at some level, the transmutation of the goals and lessons of England’s war to conquer Scotland in the 1540s.

Yet few in early modern literary studies will recognise the account I have just given. I am not aware of a single general survey of Elizabethan literature that even mentions, let alone accords any formative importance to, England’s attempt to conquer Scotland. And this is in spite of the last few decades’ upsurge of interest in literary ‘forms of nationhood’ and in ‘Archipelagic’ or ‘British’ studies.Footnote 18 As far as any project of Anglo-Scots ‘British’ union is concerned, most literary scholars think that no such thing existed until a Scottish king, James I, provoked a clash with the English House of Commons in his ill-advised attempt to force a union through against the will of Parliament.Footnote 19 This belief goes back to the 1950s, to David Harris Willson’s influential and scathing biography of James, which plotted the union project within a Whiggish narrative of escalating tensions over the royal prerogative, narrowly held in check by the tactful Elizabeth, but pushed to breaking point by James I. As a foreign absolutist, James fatally underestimated (so this version goes) both the House of Commons and the English common law. Although Bruce Galloway’s survey of the union debates of 1603–8 long ago discredited Willson’s narrative (James did not press for rapid advances to union; he moved cautiously, listened to advice from all sides, and submitted proposals to parliaments in both kingdoms) it is still widely current among literary critics.Footnote 20 Its unspoken, unexamined ground is the assumption that, were it not for England’s ‘succession problem’, Scotland as geopolitical entity, as separate, sovereign nation, would have remained a matter of complete indifference to the English. In other words, the usual story is predicated on the understanding of ‘Great Britain’ as the signifier of a Scottish monarch’s desire, a fantasy of insular integrity in which England is decidedly not implicated. Thus, for example, Claire McEachern reads the conflict between the Commons and James I over the issue of ‘Great Britain’ as one of local, gentry resistance to a hegemonic imposition.Footnote 21 Martin Butler’s extremely nuanced account of the politics of the Stuart masque identifies the terms ‘Britain’ and ‘British’ as descriptors of James’s failure to understand the ancient constitution.Footnote 22 Likewise, it is often assumed that English projects of defining Britain and Britishness are not political until the Scottish accession. Angus Vine claims that William Camden’s undertaking to solve the historical problem of Britain’s origins in Britannia (1586) might have been read as ‘a simple act of disinterested antiquarian enquiry’ which only acquired ‘a political charge’ after the accession of James I, with his project for British union.Footnote 23 In the same vein, John Kerrigan refers to the frustrations of William Drummond’s poetry writing in post-1603 Scotland as ‘the British Problem’, both anticipating the modern use of ‘British’ as a gesture of Scottish inclusion and marking that inclusion as problematic.Footnote 24

As subsequent chapters of this book will show in much more detail, it would in fact be more accurate to think of English engagements with ‘Britishness’ and ‘British history’ – whether deriving or departing from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain (c.1137) – as always already political. Moreover, these sixteenth-century English engagements with British history need to be understood as implicated in a geopolitical imperative to claim sovereignty over the whole island, as if recovering an ancient right. Alan MacColl has argued that ‘the ideological dimensions of “the British history” as it was treated in the sixteenth century remain almost entirely unexplored’.Footnote 25 Standard early twentieth-century treatments by Edward Greenlaw, C. B. Millican and T. D. Kendrick depoliticised the Tudor argument over Geoffrey of Monmouth, treating it as a pedantic wrangle, a battle of the books.Footnote 26 Through the 1990s and 2000s, Roger Mason’s and Philip Schwyzer’s innovative work on the Scottish and Welsh dimensions of Tudor Galfridian history has revealed its importance for debates over national origins, while Gordon McMullan has shown us how stories from Geoffrey of Monmouth held an extraordinary sway over the early modern English stage.Footnote 27 Still missing from this picture, however, is any detailed literary analysis of the crucial early modern English transformations of Geoffrey’s Historia Regum Britanniae in the so-called ‘Edwardian moment’ of British unionism during the 1542–50 wars.Footnote 28 This was a moment when the English Crown committed itself to realising a providential opportunity for the military recovery of the British empire of ancient Galfridian legend.

It is, therefore, a matter of some importance to reinsert the nine years of England’s attempted conquest of Scotland back into the story of the literary negotiation of English national identity within the years leading up to the accession of James VI and I. Attending to the violence and the cost of the war is also essential, for two distinct reasons. The first is that we need to counter the prevalence of the myth of England’s indifference to Scotland’s separate, independent nationhood. We need to understand the lengths to which England was prepared to go in order to realise the goal of ‘Great Britain’ and British empire by military force. The second is that literary critics need a better understanding of the stakes in the invocation of the terms ‘Britain’ and ‘British’, as well as of the image of England-as-island, in the literature and historiography of early modern England. This means that we need to acknowledge the key role that these terms and this image played in the literature of the 1540s war; specifically, in the official justifications of war emanating from the English press, which were designed to persuade English, Scots and European readerships of the legitimacy of invasion and English military aggression.

II. A Brief Introduction to ‘British History’ in the 1540s

England’s attempted conquest of Scotland in the 1540s may be seen as the last in more than four hundred years of military and discursive assertions of sovereignty grounded in what Rees Davies calls ‘British pipedreams’ – that is, ‘the memories and dreams of an imperial Britain’ in which historians from the twelfth to the fifteenth century continued to encourage their rulers.Footnote 29 If Aethelstan and Edgar, kings of tenth-century Wessex-England, had styled themselves rulers of Britain, memories of their achievements blended with dreams fostered by a Welsh history of the twelfth century, Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae or History of the Kings of Britain (c.1137). Geoffrey’s history told of the founding of an island kingdom of Britain by a wandering Trojan prince called Brutus, and of the kingdom’s subsequent division, endless wars and climactic if ephemeral reunification as the centre of a vast transoceanic empire under the rule of King Arthur. In its moment of composition, as John Gillingham has shown, Geoffrey’s History, though written for an Anglo-Norman audience, was shot through with prophetic hopes for the revival of Welsh kingship.Footnote 30 It was subsequently, however, adapted and repackaged as an English history. The sheer numbers of Brutan genealogies of Plantagenet kings that survive are evidence of how rapidly ‘this vision of English regnal antiquity … reached deep into the nervous system of English historical consciousness’.Footnote 31

What infiltrated the later deep reaches of English historical consciousness, however, was not Geoffrey alone, but what we might call the feudalisation of Geoffrey. By this I mean the use of Geoffrey’s history to uphold the claim that Scotland, as a kingdom, had anciently been feudally subject to the king of England. Kingdoms could not, as Susan Reynolds observed, be held as fiefs, but a claim to feudal overlordship of the kingdom of Scotland was advanced by Edward I in response to the succession crisis following the death without heirs of Scotland’s Alexander III in 1286.Footnote 32 In 1299, Pope Boniface VIII categorically denied that the realm of Scotland was ‘feudally subject to … the kings of the realm of England’, reminding Edward that ‘magnates of the kingdom’ had been elected for its custody on Alexander’s death.Footnote 33 Edward responded in 1301 with a famous letter which traced English overlordship back to Geoffrey’s legend of Brutus’s original division of the island kingdom of Britain between his sons, Locrine, Albanact and Camber. These sons were given the kingdoms of Loegres (England), Albany (Scotland) and Cambria (Wales), respectively. Edward, however, made two crucial additions to Geoffrey’s narrative: first, Brutus had, he said, reserved the ‘royal dignity’ or overlordship of Britain to Locrine (reservata Locrino seniori dignitate). Second, after Albanact’s slaughter by invading Huns, Albany, or Scotland, reverted back to Locrine (sic Albania revertitur ad dicum Locrinum).Footnote 34 The effect of these two minor adjustments on the subsequent political and affective power of Geoffrey’s British history can scarcely be overstated. On the one hand, Brutus’s establishment of Locrine as overlord of Albanact authorises a retrospective reconstruction of Anglo-Scots history as a continuous, unbroken relation of ‘feudal’ lordship and vassalage, in which the kingdom of Scotland is understood to be held as a fief of the English Crown. On the other, Edward’s suggestion that Brutus reserved overall sovereignty for his firstborn introduced a powerful new affective potential into the legend. It implied that the island’s division was never intended. ‘Division of the kingdom’ thus becomes a destructive aberration, the resonant original cause of the island’s subsequent painful history of strife and warfare between peoples. By this means, too, Edward’s addition redirects the prophetic energy that flowed so powerfully through Geoffrey’s Welsh history (Diana’s foretelling the destiny of Brutus; Merlin’s prophesying Arthur’s return; the voice telling Cadwalladr that the time is not yet) into imagining the future of Britain as an Anglo-imperial island.

These two modifications of Galfridian British history would have profound effects for Tudor war propaganda and its afterlife in Elizabethan English literature.Footnote 35 On the one hand, Edward’s feudalisation of Brutus’s division of the kingdom would, mediated by John Hardyng’s chronicle and forged homages, become the model for the history of overlordship with which Henry VIII justified his brutal invasions of Scotland. Henry VIII’s history, catchily entitled A Declaration, conteyning the iust causes and consyderations of this present warre with the Scottis, wherin also appereth the trewe and right title, that the kinges most royall maiesty hath to the souerayntie of Scotland (1542), became the widely cited backbone of the war’s justification. On the other hand, Edward I’s redirection of the Welsh prophetic strain of Geoffrey’s text towards the restoration of an imagined English insular integrity would be joined, in the 1540s, with a new poetic, chorographic and military-strategic awareness of the need for England’s jurisdiction to extend to the realm of Neptune – that is, for England to recover dominion over all the coasts of the island, securing it from foreign foes. This would be the theme of John Leland’s antiquarian and poetic writings of the 1540s, and would govern the strategic aims of the war under Protector Somerset’s leadership from 1547 to 1550.

In a final, influential twist, Edward I’s letter to Pope Boniface appropriated the structural and climatic centre of Geoffrey’s Welsh history – Arthur’s wearing of the royal crown at Caerleon in book IX – for proof of Edward’s possession of Scotland.Footnote 36 Arthur, wrote Edward, citing Geoffrey, ‘subjected to himself a rebellious Scotland’ and ‘destroyed almost the whole nation’, installing one ‘Augusel’ as king, who afterwards bore the sword at the famous feast at Caerleon.Footnote 37 As the early sixteenth century brought the historicity of Brutus and Arthur under pressure from sceptical humanists, Arthur’s fabled conquests and exploits were whittled back to a reliable kernel of credibility – this subjugation of Scotland. The entries for Arthurus and Britannia in the wartime (1545) edition of Sir Thomas Elyot’s Dictionary thus expressed doubts about Britain’s Trojan ancestry and the extent of Arthur’s empire, but asserted that Arthur had indeed subdued Scotland.Footnote 38

But what of Scotland’s account of its own ancient regnal history? That a Scottish counter-mythology already existed as early as the thirteenth century can be seen from the response to Edward I given by the Scottish ambassadors at the Papal Curia in 1301.Footnote 39 The full-scale history of Scotland known as John of Fordun’s Chronicle of the Scottish Nation has been dated c.1363–87, but Dauvit Broun has recently derived Fordun’s account from an earlier narrative, possibly by Richard Vairement or ‘Veremundus’, célé Dé of St Andrews and chancellor of Queen Marie de Couci, active 1239–67.Footnote 40 Vairement seems to have synthesised a number of different elements – the lives of St Brendan and St Congal, Scottish and Pictish king lists, the mid-eleventh-century Lebor Gabála Érenn (‘Book of the Takings of Ireland’), and aspects of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s history – to produce the complex story of the Scots as a people emanating from Ireland, who then became the sole inhabitants of a kingdom – Scotland – which, even while shared with the Picts, a kindred people, had been primordially coherent as a regnal territory.Footnote 41 One aspect of this narrative, blending Irish and Galfridian sources, involved a wandering prince – a Greek, this time – called Gaythelos. Having married Scota, the daughter of the Egyptian pharaoh drowned in the Red Sea, Prince Gaythelos and his bride fled from Egypt to Spain. Finding themselves oppressed, the royal pair then sent their sons to discover uninhabited lands, where they could be free. Their descendants colonised first Ireland and then Scotland, taking the royal throne – stone of Scone – from one to the other. There were other elements: the arrival of Picts in Ireland, intermarriage and the settling of both peoples in Scotland, the Pictish foundation of the metropolitan church of St Andrews, as well as the ideology of Scoto-Pictish ‘freedom’ and independence from Roman and British rule.Footnote 42 But where the Galfridian British history remained imaginatively adaptable (however discredited as history) to sixteenth-century English geopolitical priorities, this synthetic history of Scottish origins, successively chronicled by Vairement, by John of Fordun, by Andrew of Wyntoun (c.1350–1425) and by Walter Bower (c.1385–1449) grew progressively less and less effective as mythic counterweight. In 1527 a new milestone was reached when the principal of King’s College of Aberdeen, Hector Boece, published his Scotorum Historia, a fully fledged humanist transformation of Bower’s chronicle material into Latin imitative of Cicero and Livy, reconciling the synthetic Scottish history with the recently rediscovered works of Tacitus.Footnote 43 R. James Goldstein has given a fine account of the ‘war of historiography’ out of which a Scottish national literature emerged in the fourteenth century to counter Edward I’s Anglo-imperialism.Footnote 44 In the early sixteenth century, however, Boece’s elegant Livyan infill of Scottish kingship back to the fourth century BC could not compete with the cartographic imaginative power that Geoffrey’s ancient myth of Britain’s insular unity was beginning to acquire. The idea of Britain as promised island, with Troynovant-London on the Thames, hinted prophetically at how a nation defended and encircled by the sea might expand into a great trading empire.Footnote 45 Over the course of the sixteenth century, a ‘monarchical republican’ vision of English legal and constitutional exceptionality would mesh with this neo-Galfridian insular imperialism, producing a vision of an England as stretching on all sides to the sea, an island trading nation-to-be.Footnote 46 Scottish origin stories could boast no comparable vision of recovery of a lost integrity or prophecy of riches to come. Boece followed Bower in telling a story of two interwoven peoples, the Picts and the Scots, sharing land divided by mountains, the Scots always joined by the ancient highway of the sea to royal ancestors and kin in Ireland.Footnote 47 Thus, though Scots histories were as rich in their way as Geoffrey’s (if Geoffrey gives us Lear, Boece gives us Macbeth) their origin tales of Scots crossing and recrossing the Irish sea, or of Pictish kings honouring the relics of St Andrew, were weak counterpoints to a more resonant, pervasive and more easily Protestantised myth of England recovering Britain’s original island unity and religious purity.Footnote 48

The story of how English poets and lawyers transformed Galfridian myth in the later sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries will be the subject of later chapters. The rest of this chapter will analyse the foundational, dynamic and innovative part played by a Galfridian-derived myth of ‘Great Britain’ in justifying the invasion and laying waste of Scotland between 1542 and 1550. I am aware of the risk that literary critics who define their sphere of interest as ‘early modern England’ might switch off at this point, understandably reluctant to engage with Scottish materials that are ‘not relevant’ to English literature. But of course, my argument is that they are relevant, that this war is, in some sense, the unconscious of Elizabethan literature and the Elizabethan insular self-image. Let me, by way of example, invoke one obvious ‘English literature’ payoff. Most of the war texts I will be discussing enjoyed a vigorous afterlife in the history book that all critics of Spenser and Shakespeare acknowledge to be rich source of inspiration: Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles (1577, 1587).

Holinshed’s Chronicles were not only deeply indebted to historiography of the 1540s wars: they were the war’s product. Raphael Holinshed took over what had originally been a plan conceived in the 1540s by the printer, Reyner or Reginald Wolfe, for a universal cosmography. As Philip Schwyzer explains, ‘Reyner Wolfe had taken a leading role in the dissemination of the new ideology of British nationalism even before he became King’s Printer in 1546.’Footnote 49 In support of the war, Wolfe printed, anonymously, John Brende’s 1544 celebration of Hertford’s brutal campaign, The Late Expedition in Scotlande (indeed, we know this text is by the soldier and humanist translator, John Brende, only because Holinshed cites it as a source).Footnote 50 Wolfe was also the publisher of a Latin version of Protector Somerset’s wartime epistle to the Scottish nation, which, as we shall see, threatened the Scots with slaughter if they refused to embrace Anglo-imperial Britishness.Footnote 51 The poems of John Leland, in particular Genethliacon (1543) and Cygnea Cantio (1545), likewise issued from Wolfe’s press. These poems were, as Schwyzer puts it, ‘heavily imbued with Leland’s distinctive vision of British antiquity reborn in the reign of Henry VIII’. Schwyzer makes admirably clear how Leland’s poems shaped neo-Galfridian ideology: ‘[A]s if the island were already united under one imperial ruler’, he says, ‘Leland praised the future Edward VI as the darling of the British race, who would put down Scottish tumults.’Footnote 52 Within neo-Galfridianism nestled Geoffrey of Monmouth’s own history, which was, of course, ‘one of Holinshed’s core texts’, ‘fundamental’, for the early part of his history.Footnote 53 Holinshed also drew heavily on Edmund Hall’s Chronicle, a history presented as an account of English intestine war (York against Lancaster) in the Galfridian tradition of lamenting the division of the kingdom.Footnote 54

Hall’s Chronicle was another wartime production, published posthumously in 1548 (at the height of the war) by Richard Grafton who, like Reyner Wolfe, was a printer wholeheartedly committed to the Protestant, Anglo-imperial agenda of the war. In 1543, Grafton had been responsible for publishing a special war-effort edition of John Hardyng’s fifteenth-century Chronicle which, written to contextualise the author’s forgeries of documents of English title to Scotland, made the case for invasive war. Hardyng’s Chronicle was widely read: Edmund Hall drew on it, as did Holinshed and Spenser; John Dee annotated his copy.Footnote 55 William Harrison’s ‘An Historical Description of the Iland of Britaine’, which prefaced Holinshed’s Chronicles, made much use of Leland’s British Anglo-imperial writings, as well as citing another key war text printed by Grafton, An Epitome of the title that the Kynges Maiestie of Englande hath to the sovereigntie of Scotlande, continued vpon the auncient writers of both nacions from the beginning (1548) in order to justify English sovereignty over the whole island.Footnote 56 Holinshed’s Chronicles, in other words, were saturated, in every section, and across every period and national boundary, with the ideological justification of England’s invasion of Scotland in the 1540s. Thus, although the ignominy of defeat in 1550 was, in some senses, forgotten, the war’s self-justifying arguments for Scottish non-nationhood pervaded Elizabethan historiography, with important consequences for James’s attempt at ‘British’ union in 1603.

What follows, then, sets these sources of Holinshed back amid the violence, the burning, shooting, raping and looting that their arguments were designed to justify in 1542–50. This chapter and the next tell a story of ideological and military transition, from the simple overlordship argument supporting Henry’s high-handed but distracted campaign of punitive devastation, to Protector Somerset’s more complex harnessing of the visionary potential of Geoffrey’s island myth in the service of an amphibious military strategy and of a propaganda campaign which cast Scottish resistance to conquest as impeding God’s provident plot for the invincible island of ‘Great Britain’.

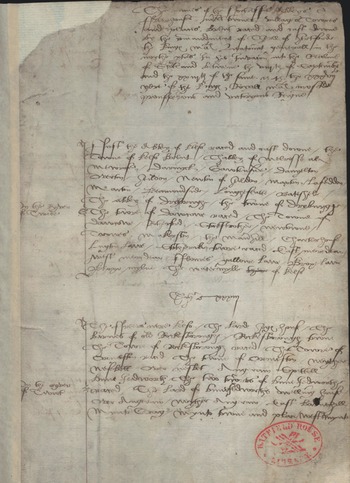

III. ‘If we had minded the possession of Scotland’: Occupatio, Distraction and Henry’s Wars, 1542–1547

Among Cecil’s papers at Hatfield House, as well as in the State Papers, there exists a detailed itinerary, like a tourist trail, of edifices that lined the banks of the river Tweed and its tributaries in the autumn of 1545 (see Figure 1.2 in plate section). The text is divided by waters and parishes, ‘On the river of Twede’, ‘On the River of Tiviot’ (Teviot), ‘On the Water of Rowle’ (‘Rule’), ‘On the Ryver of Jedde’ and so forth. The buildings range from magnificent ancient monastic abbeys filled with treasures and manuscripts – Kelso, Melrose, Dryburgh, Jedburgh – to water mills, villages and ‘spitals’ (lepers’ hospitals). At first glance, the text almost reads like one of John Leland’s ‘laborious journeys’ along rivers and fenny waters in search of antiquities.Footnote 57 But no – there are those infrequent but dismaying past participles – ‘raced and cast down’, ‘brent’, ‘raced’, ‘raced’, ‘raced’. And then, at the end of every section, a numerical sum. This is no gentle tourist meander round the border abbeys, but a meticulous casting of the accounts of a rampage. In the Hatfield House manuscript, the location is given to the left of a beautifully ruled vertical line, to the right of which is the list of places destroyed. Underneath, neatly centred, are the totals for each district, in roman numerals.

Fig. 1.2 ‘The Invasion of Scotland, September 23, 1545’, The Cecil Papers, vol.137. fol. 116.

- On the ryver of Twede.

First, the Abbey of Kelso raced and cast down; the Towne of Kelso brent; the Abbey of Melrosse alias Mewrose, Darnyke, Gawtenside, Danyelton, Overton, Heildon, Newton of Heildon, Maxton, Lafeddon, Marton, Beamoundside, Loughflatte, Bateshele, the Abbey of Dryburghe, the Town of Dryburghe, the Towre of Dawcowe raced, the Town of Dawcowe, Rotherford, Stockstrother, Newtowne, Trowes, Makerston, the Manorhill, Charter-house, Lugton Lawe, Stotherike Towre raced, East Meredeane, West Meredeane, Flowres, Gallow Lawe, Broxe Lawe, Broxe Mylne, the Water-mill of Kelso.

Summa .xxxiij.

- On the River of Tiviot.

The Freers [Friars] near Kelso, the Larde Hog’s House, the Barnes of Old Rockesborough, Rocksburgh Towne, the Towre of Rockesborough raced, the Towre of Ormeston raced, the Towne of Ormeston, Neyther Nesbett, Over Nesebet, Angeram Spittell, Bune Jedwourth, the two Towre of Bune Jedworth raced, the Laird of Bune Jedworth’s Dwelling house, Over Angeram, Neyther Angeram, East Barnehill, Mynto Crag, Mynto Towne and Place, West Mynto, the Cragge End, Whitrick, Hessington, Bankehessington, Overhassington, Cotes, Esshebanke, Cavers, Bryeryardes, Denhome, Langton, Rowcastle, Newtowne, Whitchester-house, Tympinton.

Summa .xxxvij.

- On the Water of Rowle.

Rowle Spittel, Bedrowle, Rowlewood. The Wolles, Crossebewghe, Donnerles, Fotton, Weast Leas. Two Walke Mylnes. Tromyhill, Dupligis.

Summa .xij.

- On the Ryver of Jedde.

The Abbey of Jedworthe, the Freers [Friars] there; the Towne of Jedworthe, Hundylee, Bungate, the Bank End, the Neyther Mylnes, Houston, Over Craling, the Wells, Neyther Craling, Over Wodden, Neyther Wodden.

Summa .xiij.

The list goes on, six pages in all, several more paragraphs of names, concluding with an overall total, and then numerical calculation of the destruction according to building-type (monastery, castle, town, mill, hospital):

Summa totalis cciiijxx vij. In monasteries and fryres houses vij. In castelles, towres and pyles xvj. In merket towns v. In villages ccxliij. In mylles xiij. In spitelles and hospitalles iij.Footnote 58

A grand total of two hundred and eighty-seven places have been ‘brent, raced, and cast downe’ at the commandment of Edward Seymour, earl of Hertford, as part of the ‘Invasion into the Realme of Scotland’ between the 8th and the 23rd of September, 1545. The manuscript renders Hertford’s stewardship of his charge to the privy council and the king. It applies the formulae of memoranda (neatly ruled lines, headings, items separated by commas, summed up in totals) to conjure their antithesis, obliteration: flames and cannon-shot tearing through roofs and walls, hovels and towers flattened, people terrorised and shot at close range, livestock plundered, the treasures of the abbeys violently desecrated and looted. Record-keeping obscures the annihilation it would represent.

This document’s shocking clash of presentational styles, oscillating between affectionate chorography and military reconnaissance, or a sober casting of accounts and an orgy of iconoclasm, attests to the complexity of England’s imperial project of conquering Scotland in these years. It adumbrates, perhaps, differences between Henry’s ideological priorities and those of the earl of Hertford that were to emerge when, on Henry’s death in 1547, Hertford took over the war as the duke of Somerset, Lord Protector of England. One’s sense, for example, of an uncanny resemblance between this topography of oblivion in the Scottish borders and John Leland’s contemporaneous memorialisation of the British antiquities which he tracked along the ‘washes, lakes, meres, fenny waters’ of Henry’s dominions, is surely no accident.Footnote 59 Leland’s derivation of the traces of British histories of Brutus and Arthur from the Anglo-Welsh natural landscape was no nostalgic perambulation through monastic ruins. It was, rather, as Cathy Shrank has shown, an inventive Protestant humanist history, designed to enrich England’s identification as ‘Britain’ by way of locating the mythic history of that claim in the writing of landscape. At the same time, as Shrank also notes, Leland’s topographic description has affinities with the rise of cartography as a military resource.Footnote 60 Cartographic historian Peter Barber has noted that Henry VIII’s reign was ‘a watershed in the history of map consciousness and map use’.Footnote 61

In the 1540s, a new humanist conception of the effective power of eloquence combines with a new appreciation of the uses of cartographic and hydrographic knowledge, as expressed in the concept of the ‘plat’. This word ‘plat’ fused ideas of spatial mastery and future-oriented provision of material resources (such as military supply to an army in hostile territory) with ideas of rhetorical persuasion, which guarantee the commitment of human allegiance and assistance. Plats were, as I have elsewhere written, ‘at once conceptual schemes for the better organization of means and resources and the discursive order or “emplotment” of their probable success’.Footnote 62 During the wars of the 1540s, letters show Hertford ‘constantly evaluating and commissioning plats for the information of his master’.Footnote 63 One of these, indeed, was Hertford’s ‘plat’ for the fortification of Kelso Abbey on this very 1545 campaign. Rejected by Henry and the privy council, the waste of this plat is implicitly marked as Kelso’s prioritisation in Hertford’s account of laying waste: ‘On the ryver of Twede … First, Abbey of Kelso raced and cast down’.

Thus, the perceptible clash of style and substance in this document may acknowledge, among other things, a tension between the somewhat haphazard and distracted nature of Henry’s conduct of the war in 1542–7 and Hertford’s sense of the provident accountability of iconoclasm itself. These two contrasting styles of military leadership of the war might be characterised as the mode (in Henry’s case) of strategic preoccupation or absence of mind, while Hertford/Somerset conceived the war as a realisation of God’s providential ‘plat’ for Britain. Henry VIII would keep contemporaries and modern historians guessing about his intentions in Scotland. For example, William Thomas’s Peregrine, written in exoneration of Henry VIII after his death, describes a dinner party in Bologna at which his Italian hosts accuse Henry of having ‘wasted … no small parte of Scotlande with entent to subdue the hole without cause or reason’.Footnote 64 Protector Somerset, by contrast, would leave no one in any doubt of his ‘entent’ to unite the nations of Britain, he and his propaganda team providing endless iterations of causes, reasons and considerations for the army to proclaim as they burned and looted. Somerset, indeed, conflated rhetorical persuasion with military coercion in ways which would be ultimately self-defeating. His neo-Galfridian vision of an island empire of Great Britain, a mythical ancient unity recovered for godly and profitable future required the buy-in of the Scots in a way that Henry’s mere assertion of sovereignty did not. Both, however, as we will see, licensed a contempt and brutality towards their addressees that contradicted their professed objectives of a peaceable dynastic union.

In 1544–7, Henry failed, diplomatically and militarily, to achieve the betrothal of Mary Stewart (Mary Queen of Scots) to his son Edward. This was partly because he regarded efforts in Scotland as ancillary to more important conquests in France. It is also, however, because he really believed in his title to Scotland and overestimated the extent to which Protestant enthusiasm for union with the English might outweigh fears of English tyranny. Henry’s Declaration is not a complex or especially persuasive text and most historians let its titular description of its contents stand in for any analysis of the text itself. Its exceptional influence, however, obliges us to attend to it more closely. ‘Virtually every single future English pronouncement accepted its case’, not just for the duration of the war, but beyond, in the establishment of the constitutional relation between Scotland and England after James’s accession.Footnote 65 Before we turn to the text itself, however, we need to look at the military activity that it justified.

It is tempting, as I have suggested, to imagine that, in the almost parodic form of Hertford’s meticulously itemised invoice of violence in the borders, one can detect a feeling of frustration at having to carry out Henry’s scattershot orders without being able to build, militarily and in propaganda terms, on these successful raids. In the previous spring, of 1544, Hertford had received instructions from the king to capture Edinburgh Castle and its port of Leith and fortify them both. But plans suddenly changed. Henry, on the point of invading France, no longer wanted fortifications in Scotland. He now wished simply to ‘devastate their countrey’, precluding the possibility of military aid from Scotland’s allies, France and Denmark. ‘His majesties pleasure’, the privy council now told Hertford,

is that ye shall forbeare to make the forsayde determined fortification either at Lythe or at the sayde mount, but only for this journey put all to fyre and swoorde, burne Edinborough towne, so rased and defaced when you have sacked and gotten what ye can out of it, as there may remayn forever a perpetuel memory of the vengeance of God lightened upon [them?] for their faulsehode and disloyailtye. – Do what ye can out of hande, and without long tarying, to beate down over throwe the castle, sack Holyrod house, and as many townes and villaiges about Edinborough as ye may conveniently, sacke Lythe and burne and subverte it and all the rest, putting man, woman and childe to fyre and swoord without exception where any resistence shalbe made agaynst you, and this done, passe over to the Fyfeland and extende like extremityes and destructions in all townes and villaiges … not forgetting among all the rest so to spoyle and turne upset downe the Cardinalles town of St Andrews, as thupper stone may be the nether, and not one stick stande by an other, sparing no creature alyve within the same … And yf ye see any likelyhode of winning the castle, gyve sum stout assay to the same … and destroye it pece meale … do nothing but such as ye see may easely be achieved.Footnote 66

The instructions combine ludicrously unrealistic ambitions (to overthrow Edinburgh Castle and destroy St Andrews Castle ‘pece meal’) with a deprecating dismissiveness that must have irked: ‘Do what ye can out of hande’ (i.e. ‘don’t go to any extra trouble’); burn places ‘as ye may conveniently’ (i.e. ‘don’t go out of your way’) and ‘this done, passe over to the Fyfeland’ (there was clearly no time to get over to Fife in Henry’s new schedule). There is also, in the exuberance of the vision of the Cathedral and Castle of St Andrews turned so ‘upset downe’ that ‘thupper stone may be the nether’, a suggestion of the energy with which the Reformation, as Robert Scribner has argued, assimilated the verkehrte Welt or ‘world upside-down’ of carnival and radical Christianity.Footnote 67 Hertford, however, declared that he was grieved ‘to see the King’s treasure employed only in devastating two or three towns and a little country which would soon recover’.Footnote 68 But Henry’s distraction by the greater prize of France did not preclude his sense of the importance of this expedition of admonitory devastation. Hertford was to ‘put man, woman and childe to fyre and swoord without exception where any resistence shalbe made agaynst you’. This he most certainly was able to do.

As it turned out, Edinburgh Castle proved impregnable. The English were gunned down as they tried to approach by the only way possible – along the Royal Mile. Sir John Brende lamented ‘the loss of divers of our men with the shot of the ordnance out of the said Castle’, noting approvingly that Hertford determined not ‘to waste and consume our munition about the siege thereof’ but rather ‘utterly to ruinate and destroy the said town with fire’.Footnote 69 Edinburgh sent out its provost, Adam Otterburn, to ‘remonstrate against such unlooked for hostilities and propose an amicable adjustment of all differences’.Footnote 70 But the citizens could not possibly accept Hertford’s terms, which were the immediate delivery of Scotland’s infant queen into Henry VIII’s custody. Hertford ordered his soldiers to ‘put the inhabitants to the sword’ and then burn the town. ‘Neither within the walls nor in the suburbs was any house left unburnt’ Brende noted with satisfaction. The Abbey and Palace of Holyrood House were also destroyed; the army then ‘burnt every stick’ of Leith harbour, capturing ships and departing ‘pestered’ with booty, the spoils of Scotland’s trade from France, Denmark and Flanders. On the way south, for good measure, they ‘suffocated and burnt’ the inhabitants of Dunbar as they slept.Footnote 71

In 1545, John Leland flattered Henry by celebrating the Hertford’s 1544 campaign as a great success. ‘Scotti perfidiae graveis tulerunt / Poenas’, he wrote, ‘The Scots paid heavy forfeits for their treachery’ describing how ‘Leith is prostrate, wholly reduced to sad ashes’.Footnote 72 Blatantly stretching the truth, Leland declared that Edinburgh Castle had been brought to ruin by fire and steel, and that this victory, along with Henry’s capture of Boulogne, showed the favour of Neptune to the British.Footnote 73 But for Hertford, the frustration of neither being able to garrison nor to build on Leland’s fervent propaganda, was to recur in the 1545 campaign on the borders. This time, as I have mentioned, he proposed to fortify the magnificent Romanesque Abbey of Kelso, a Tironensian establishment founded by David I in the twelfth century. For this Hertford had royal approval: Henry ‘lyketh very well your nue platte’, he was told. But once again, plans changed: Hertford was not to proceed with this fortification.Footnote 74 Frustrated, he utterly demolished the abbey. The monumental west tower still soars skyward amid the ruins of that assault in 1545, its dwarfing of all adjacent buildings a striking index of the grandeur and scale of what was destroyed that day.

In Hertford’s army was a Protestant Highlander called John Elder, a fervent supporter of Henry VIII’s Reformation, who wrote to William Paget, describing the operation with relish. Hertford’s army marched towards the abbey, wrote Elder, with a discipline that Vegetius and Frontinus would have approved. When they met resistance from some monks and ‘hackbuttiers’ within (that is, soldiers with arquebusses or musket-like firearms), English forces drew up a cannon and fired it, while shooting into the windows so fiercely that none could peep out. Two hours’ battery threw down the choir ‘where such a noise was as I have seldom heard’, wrote Elder, ‘what of those that entered, and what of them that were within, calling and crying for mercy’. Hertford, he declared impressively, had ‘made all the abbeys upon the Twide tremble in a day’.Footnote 75 Elder’s conclusion of the letter with an itemisation of destruction in Tweedside, Teviotdale and Jedburgh suggests that he may even have provided the local knowledge for the fuller reckoning with which we began.

So why was Scotland held to be deserving of such treatment by an English royal army in 1544 and 1545? Leland referred to the Scots’ perfidia, their faithlessness. Likewise, Anthony Cope’s 1544 translation of Livy on Hannibal and Scipio encourages Henry VIII’s military efforts against ‘the promisse breakers the double dealyne Scottes’.Footnote 76 Englishmen understandably thought the Scots perjured because they had, under their governor, James Hamilton, the earl of Arran, broken the Treaty of Greenwich (1 July 1543) according to which the country’s queen, the infant Mary Stewart, would be betrothed to Henry’s toddler son. This might sound a reasonable ground of war, but Henry had, in negotiating the Treaty of Greenwich, stipulated conditions that it would be impossible for a sovereign nation to accept. He did this because he regarded himself as Scotland’s true sovereign, and because he felt already aggrieved by perceived slights to his suzerainty on the part of Mary Stewart’s late father, James V, who was his sister’s son. During the reign of James V, Henry had hoped to persuade his young nephew to join him in breaking with Rome and reaping all the consequent financial benefits of monastery dissolution. He had probably felt quite confident in this strategy, for there were indeed signs of growing numbers of Scots enthusiastic about the new Protestant learning. Thomas Cromwell was told, in 1539, of Scots fleeing to England daily for ‘reading of the Scriptures in English’.Footnote 77 But James, though tolerant, or even encouraging, of reformers, already controlled so much of the Scottish Church’s patronage and wealth that he had no financial incentive to dissolve its monasteries.Footnote 78 Henry seems not to have informed himself about Scotland enough to have understood this, so that what he perceived as James’s ‘defiance’ in receiving English Catholic refugees, and in refusing to keep an appointment at York, stoked his anger. Henry then sent a force into Scotland under the duke of Norfolk in 1542, and in retaliation, James mustered an army which met the English on the Esk, near the Solway Firth. The English won the field, known as Solway Moss, taking large numbers of Scottish noble prisoners, from whom they took pledges or hostages, on the assurance that these noblemen would, on their return to Scotland, advance Henry’s cause. Shortly afterward, James V died (probably of cholera), leaving a daughter and heir who was a mere six days old. This, then, seemed to Henry a providential sign of the rightness of the time to recovery his ancient title to Scotland. He had already published his Declaration. He had all his ‘assured’ noblemen from Solway Moss ready to support him. It seemed as if Scotland was ready to embrace Protestantism and union with England. He had a son of perfect age to be betrothed to this infant female heir to the Scottish throne. The earl of Arran, Scotland’s governor, though not the brightest nor most reliable of people, seemed encouraging. Nothing, it must have seemed to Henry, could stop him now. He could recover his ancient right in Scotland without any effort at all – he could even do so without paying much attention, while he concentrated on war with France.

But from the outset, Henry’s assumption of his right to Scotland made the Scots uneasy about the marriage. Scottish ambassadors, arriving in London to negotiate the betrothal, conveyed the articles agreed by their Parliament, according to which, once the queen ‘being of perfit aige & mareit in Ingland’, Scotland should continue to ‘evir haif and beir the Name of Scotland’ with ‘all the auld liberties, priuileges and fredomes … as it hes bene in all tymes bigane and salbe gidit & gouernit vnder ane gouernour borne of the realme selfe’, with continuance of the College of Justice and other institutions.Footnote 79 Henry’s aims, as Alec Ryrie has neatly summarised them, were quite different:

Henry’s hopes … were nakedly expansionist and imperialistic. The old English claim to feudal suzerainty over Scotland had been revived in 1542, and during 1543 Henry never allowed it to recede too far into the background. He wanted a marriage treaty, and one which would deliver the Queen of Scots into his own custody. He also wanted the title of Governor of Scotland for himself. He was ready, if necessary, to send an English army into Scotland to secure these objectives. And he did not want to make any guarantees regarding Scotland’s laws and liberties, or regarding what might happen if either Prince Edward or Queen Mary died before the marriage could be solemnised. The marriage was, for Henry, a form of conquest, and his patience with the Scots was vanishingly short.Footnote 80

The negotiations quickly unravelled. The Scottish ambassadors wanted a clause in the treaty that would provide, in the event of Mary’s death before the marriage, for the Scottish crown to go the next heir of blood, ‘which’, as Henry wrote to his ambassador in Scotland, Sir Ralph Sadler, ‘should have implied a grant that there rested in us no right to that realm’.Footnote 81 But Sadler himself was writing back to Henry, explaining that the Scots would not concede his title; even Henry’s ‘assured’ noblemen found English conditions for immediate custody of Mary unacceptable. One of these, Sir George Douglas, explained to Sadler why Henry’s demands would not work. Take the long view, Douglas advised Sadler. If the betrothal goes ahead and Mary is permitted to reside in Scotland, brought up by nobles from both countries, over time, free intercourse between the countries would build amicable relations and trust. ‘[T]hat that is so wonne in tyme with love shall remayne for ever’, said Douglas, but the English had ‘often won with force, which hath engendred hatred’. To lay down such conditions as Henry wanted to impose so arbitrarily and immediately

‘… to bring the obedience of this realme to Englonde … is impossible to be don at this tyme, for’, quod he, ‘there is not so lytle a boy but he woll hurle stones ayenst it, the wyves woll com out with their distaffes and the comons unyversally woll rather dye in it; yee and many noble men and all the clergie fully ayenst it, so that this must nedes folowe of it’.Footnote 82

But Henry was not prepared for a gradual approach. By the autumn of 1543 the treaty was dead, and by December Henry had declared war; in the spring of 1544 Hertford was sent north with an army of arquebusiers and heavy artillery to impart the necessary lesson in obedience.

What of Scottish Protestants, enthusiastic for the marriage? The highlander John Elder, already mentioned, seems to have been unusual in committing himself not only to Protestantism and Anglo-Scots union, but to the English monarchy’s claims to suzerainty. In a letter to Henry VIII he offered his services and a ‘plotte’ or map of Scotland, which, he argued, was inhabited by wild Irish until ‘Albanactus, Brutus second sonne’, reduced it to civility.Footnote 83 He thus adapted the Galfridian story of Brutus and his sons to the Irish-Scots origin story, going so far as to blame the myth of the Egyptian Scota on the Catholic clergy. He held the Scottish clergy wholly responsible for obstructing union between England and Scotland, reserving his greatest loathing for Scotland’s ‘pestiferous’ Cardinal David Beaton. Elder’s was a rather extreme position, however. The poet David Lindsay, for example, did not subscribe to English suzerainty over Scotland. Yet, sympathetic to Protestantism, he shared Elder’s opinion (as did many Scots) of Cardinal Beaton’s venality. Lindsay’s writings on this subject thus inadvertently supported the English propaganda which encouraged Scots to thank the cardinal for the havoc wrought on their country.

With brilliant, deadpan irony, Lindsay’s Tragedie of the Cardinall, written after Beaton’s assassination in 1547, allows the revenant cardinal to condemn himself out of his own mouth. The poem opens with the author, immersed in Boccaccio’s stories of fallen princes, suddenly interrupted by the apparition of a wounded man, bleeding profusely over his crimson satin robes. This gruesome figure declares, blasphemously yet somehow with camp bravado, that there never was pain like to his ‘passioun’ and that he is quite sure Boccaccio would have loved to write it.Footnote 84 As he proceeds, with gusto, to narrate his own life story, cheerfully boasting of his brilliant career moves and his self-serving pro-French and pro-Rome diplomacy, the reader infers, in the poem’s ironic undertow, all the corruption and misgovernment that will end in Scotland’s sorry tragedy. ‘Of all Scotland I had the governall,’ Beaton’s ghost brags, ‘But my avyse concludit was no thyng.’Footnote 85 Appalled to find that a marriage with the heretic England had been contracted behind his back, the cardinal gleefully brags that it was through his ‘pratyke and ingyne’ that Arran was persuaded to dissolve the Treaty of Greenwich, causing England to respond with ‘mortall weirs’:

Lindsay’s poem was instantly recruited to the English cause, feeding into the writings of English Reformers, some of whom fought under Hertford/Somerset against the Scots in 1547, confident in the godliness of their cause. The Tragedie was published in an Anglicised version as early as 1548 by the evangelical printer John Day, where it was joined to a prose account of the martyrdom of George Wishart. John Foxe quoted from this edition in his Book of Martyrs and it seems quite likely that it offered a model for The Mirror for Magistrates.Footnote 87 For all its wit, then, what Lindsay’s poem chiefly reveals in the war context is the shrinking of a thinkable space of Scottish resistance to the violence legitimised by the argument of Henry’s Declaration. It was hard to articulate Protestant sympathies and to express anger with Beaton’s and Arran’s self-serving failures of government, without endorsing the implication that these atrocities were justified as part of the English monarch’s recovery of ancient title to Scotland.

In a striking illustration of this, Lindsay’s vision of Lothian and the Borders cursing Beaton’s wet-nurse had itself been precisely anticipated by the propaganda that accompanied the 1544 and 1545 campaigns. Henry and the English privy council had already instructed Hertford to be sure to lay the blame for his massacres at the door of Cardinal Beaton. A telling exchange in early 1544, however, reveals the contradictions of this strategy, foreshadowing the more complex propaganda message that Hertford would try to pursue when he took charge of the war. Henry had commanded Hertford when making ‘rodes and burnings’ to ‘set bills on the chirch dores or other notabull plasis, purporting in the samme they might thank ther Cardinall therfor’.Footnote 88 Hertford, however, wanted to improve on this simple clerical scapegoating by composing a proclamation which explained and justified the legitimate ‘causes’ of the violence more fully and in such a way as might persuade or ‘indeuse others to your majestes porpos’. In Hertford’s media strategy, the whole project of Anglo-Scots union through the marriage was to be set out, stressing the mercy of Henry, who ‘notwithstanding the just titulle and intrest that his highnis hath unt[o] this reaulme of Skotland’ was nevertheless willing to negotiate with the Scots Parliament. The obstinate refusal of the Scots Parliament to accept Henry’s conditions for immediate custody of Queen Mary ‘as her next kynsman … chef govrner and rewlar’ would then be given as the cause of Henry’s sending Hertford ‘with his armi royall for to requiar and demand the deliveri of her saffli’. Henry and the English privy council responded to this suggestion with a tactful but firm negative. The publication of such a proclamation at Hertford’s first entry into the country would be, they said, ‘inexpedient’ because it would make it difficult for Hertford to set about burning and despoiling Scotland, having just declared Henry chief governor of the Scotland’s queen, and the country’s protector.Footnote 89 Better simply to blame the cardinal than to provoke the question of why Henry was putting a torch to a realm which he was supposed to protect.

This dispute over the propaganda message reveals how much Hertford was invested in what I earlier described as reading for the ‘plot’ or ‘plat’. As we will see in Chapter 2, Hertford’s conduct of the war from 1547 was characterised by this future- and spatially- oriented strategic thinking, in which the objectives of mastering unfamiliar terrain and providing military supply were conflated and confounded with those of ‘persuading’ the Scots of the probability and justice of the English cause. Yet even Hertford’s post-Henrician strategy built on the premise of Henry VIII’s Declaration, which defined the Scots as ‘rebels’ to their English sovereign. To this extent, Hertford’s strategy was itself divided. Its attempt to recruit Scottish support by means of a visionary rhetoric of fraternal British union – the plat of Great Britain, in which English and Scottish might collaborate as equals – was inherently in conflict with the tacit conviction that the Scots simply owed their allegiance and assistance to the English, and that any withholding, any resistance to invasion, was a punishable rebellion.

IV. Henry VIII, War Criminal: Lamb’s Ane Resonyng

To understand this clearly, we need to move in to get a closer look at Henry VIII’s Declaration. Its model turns out to be quite venerable: it derives from Edward I’s commissioning of historical proofs of Scottish homage from English monastic chronicles as published in the Great Roll of John of Caen (1297) in order to justify his invasion.Footnote 90 So effective was Henry’s reprising of Edward’s case that it persuaded the English Parliament to pass a Subsidy Act to finance Hertford’s expensive Scottish campaigns. The Subsidy Act’s preamble referred to the perfectly legitimate King James V as ‘the late pretensed King of Scottes, being but an Usurper of the Crowne and Realme of Scotland’. James’s death, it added, was God’s providing of ‘a tyme apt and propyse for the recoverye of [Henry’s] saide right and tytle to the saide Crowne and Realme of Scotland’.Footnote 91

Henry’s Declaration is split into two halves, both written in the first person, as if voicing the embodied sovereign authority of the King of England. In the first half, the king speaks in the persona of a caring but exasperated older kinsman, an uncle whose patience with his nephew’s failures of respect has finally run out. The opening sentence is a master class in passive aggression, its declaration of war disguised as a regretful correction of former indulgence:

BEYNG NOW ENforced to the warre, which we haue always hitherto so moch abhorred and fled, by our neighbour and Nephieu the kyng of Scottis, one, who, aboue all other, for our manyfold benefits towardis him hath most iust cause to loue vs, to honor vs, and to reioise in our quiet: we haue thought good to notify vnto the world his doings and behauiour in the prouocation of this war.Footnote 92

The litany of James’s ‘doings and behauiour’ that have provoked an armed response include James’s failure to keep an appointment with Henry at York; his entertainment of Catholic ‘rebels’ from England; and his having ‘vsurped’ a small piece of border land ‘of no great value’ in spite of English commissioners having shown ‘autentique’ evidence of its belonging to England.Footnote 93

It was, however, the second half of the treatise that exercised influence for decades, perhaps centuries, to come. The second half purported to be a redacted history of England’s feudal tenure of Scotland, starting with Albanact’s submission to his elder brother and overlord, Locrine, and ending with the homage performed by James I to Henry VI. Henry introduced it with a disclaimer, denying that he had ever sought to possess Scotland, in spite of his right to it: ‘If we had minded the possession of Scotland, and by the motion of war to atteyne the same, there was neuer kynge of this realme … had more iuste title, more euident title, more certayn title, to any realme that he can clayme, than we haue to Scotland’.Footnote 94 This statement, at once absolute and disparaging, justifies the military assertion of title, while disavowing motivation, interest and desire. It was to become a familiar formulation. William Thomas refuted the Italian accusation that Henry VIII had wasted Scotland unjustly with intent to possess it by arguing that the English king took up arms ‘Not for the wealth of the Scottyshe domynion which in respect of Englande is of as good a comparison, as the barain mountaignes of Savoie unto the beaultie of the pleasannt Toscane, but for the uniforme quiett of their approved anncient contention.’Footnote 95 It is important to see that in these and other variants of the formulation, the denial of intent to possess exists in a productively uncertain relation with the assertion of title. Henry’s conditional (‘If we had minded the possession of Scotland’) like Thomas’s denial (‘Not for the wealth of the Scottyshe domynion’) disguises England’s insular imperial ambition as restraint, while the military pursuit of that ambition is figured as a mere corrective to a title denied. William Thomas defines Henry’s object as ‘the quiett of their approved anncient contention’, while Henry himself protests, ‘We haue euer been alwayes glad … to omyt to demaunde our right … than by demaundyng therof to be sene to moue war.’Footnote 96 War becomes the result of Scots resistance, literally in spite of commendable English restraint in pursuing possession. Denying any intention to possess because/in spite of already having possessive title is thus no ornamentally ambiguous figure; its ambiguity makes it a foundational trope of Tudor Anglo-imperialism with respect to Scotland. Even today, historians continue to assume that the question to ask is whether Henry was ever serious about possessing Scotland. This question obscures the truth that Henry’s stance of disparagement and disavowal is a part of a claim of always already being in titular possession. This stance is highly adaptable to the political occasion. It can justify war; it can render a Scottish succession unthreatening; it can justify the refusal of reciprocal rights and common nationhood – and in time it did all these things.

The rest of the treatise’s second half is narrated as a summary history of Anglo-Scots relations from the time of Brutus’s division of Britain, listing twenty-two acts of homage performed by Scottish kings to their English ‘overlords’. Ostensibly the fruits of Cuthbert Tunstall’s research in the Durham archives, this is largely a fairly close translation of the entries in John of Caen’s Great Roll, which compiled the monks’ findings, in response to Edward I’s instruction, of records of ancient Scottish homages.Footnote 97 As E. L. G. Stones has written, Caen’s entries follow the formula of recording a homage, dating it, and then giving a list of the chronicles where it may be found. The dates are ‘clumsily done’ and the records often misrepresent the homages as recorded by the chroniclers in question. Clauses explaining that the homage was for lands in England, and not for the realm of Scotland, are omitted.Footnote 98 The historical specificity of Anglo-Scots agreements in their political contexts disappears, as does any mention of treaties releasing Scottish kings from former obligations, such as the Quitclaim of Canterbury (1189) and the Treaty of Northampton (1328). In the Declaration’s version, moreover, Henry asserts that one after another of his ‘progenitors’ received homage from this or that Scottish king at such and such a date. The text thus designedly creates the impression of the king himself asserting an overlordship of Scotland as old as his own royal genealogy, a feudal inheritance lineally and uninterruptedly descended from his forebears. Yet, as hardly needs saying, no such inheritance of title existed. Assertions of sovereignty over Scotland made by early English kings were contingently military and political and were resisted as such.Footnote 99 But John of Caen’s Roll, like Henry VIII’s Declaration, produced history as a legal record of tenure ab initio, according to which the kingdom of Scotland had been held as a grant from England ever since Albanact first received it of Locrine.

Henry’s history opens with a version of Geoffrey’s Brutus legend which stresses his naming of ‘Britayn’ and determination to have his three sons govern ‘the whole Isle within the Ocean sea’ hierarchically, with the younger sons doing homage to Locrine. This primal overlordship legitimises Henry’s declaration of war by setting it in a history of regular ‘transgression’ by Scots kings and ‘chastisement’ by their English superiors. We are to learn, ‘howe for transgression against this superioritie, our predecessours haue chastised the kinges of Scottis, and some deposed, and put others in their places’.Footnote 100 The narrative then moves swiftly over the rest of Geoffrey (‘passinge ouer … the victories of king Arthur’) and proceeds to Caen’s Great Roll. The Declaration follows Caen closely, for example, on Aethelstane: ‘Athelstane … hauynge by battayle conquered Scotlande, he made one Constantine … to rule and gouerne the countray of Scotland vnder him, adding this princely woorde, That it was more honour to hym to make a kynge, than to be a kynge.’Footnote 101 This entry refers to Aethelstan’s invasion of Scotland in 934, and Constantín’s being forced to submit to him as ‘subregulus’ to the ‘rex et rector totius Britannia’, as well as to Aethelstan’s 936 victory over Constantín and the Northumbrians at Brunaburgh or Dún Brunde.Footnote 102 An important victory for Aethelstan, wonderfully celebrated in the poem, The Battle of Brunaburgh, Brunaburgh by no means led to an enduring governorship of Alba by the kings of Wessex.Footnote 103 The Declaration’s contrary impression is merely the effect of sequential structure. Further examples of translations of Caen include the homage allegedly performed by Alexander III at his marriage to Henry III’s sister in 1251, but no mention is made of the dispute about the homage in question.Footnote 104 For homages that post-date Edward I, Henry’s Declaration is largely reliant on John Hardyng’s forgeries, discussed in Chapter 5, below. The preamble to the Subsidy Act of 1543 expressed Parliament’s satisfaction that ‘divers and soondrye old auncient and autentique rolles patents, wrytings and recordes’ had been ‘maturelye redde and debated in this present parliament’ to prove that Henry ‘hath good juste tytle and interest to the Crowne and Realme of Scotlande’.Footnote 105

The immediate and enduring consequences of Henry’s Declaration – initially as justification for war, subsequently as a foundation of Anglo-Scots constitutional relations – were immense. The text’s performance of Henry’s royal personae (outraged uncle; disinterested possessor of Scottish sovereignty; patient sufferer of Scottish wrongs) coupled with the ostensibly referential clarity with which it set out proof of English title, would make refutation a daunting task. Yet the task was undertaken with qualified success in 1549 by a judge of the Scottish College of Justice, William Lamb.Footnote 106 Lamb’s remarkable work takes the form of a fictional dialogue between an English and a Scottish merchant, who, as travelling companions on the road to Lyons from Rouen, debate the justice of the current war in Scotland. The text, Ane Resonyng of ane Scottis and Inglis Merchand Betuix Rowand and Lionis, comes to us unpublished (though apparently prepared for publication) and unfinished, with some rather gaping holes in the fictional structure. Nevertheless, the fiction’s very conception is eloquent, for it throws into startling relief the artifice of the insular English perspective to which we are generally so habituated as to find it natural.

Discussions of Scots responses to Henrician and Edwardian war propaganda have tended to pay more attention to the Protestant ‘unionist’ arguments of John Elder and James Henrisoun (of whom more in Chapter 2), partly because they give evidence of a forward-looking pragmatic humanist interest in a united British commonwealth in what Arthur Williamson calls the ‘Edwardian moment’.Footnote 107 Evidence of Scottish ‘nationalism’ tends to be written off, by implication, as anachronistic and irrelevant to the extent that, conformist in its Catholicism, it looks back towards the supranational authority of papacy. But Lamb’s Resonyng looks not to Rome, but to European trade routes. However thinly sustained, its foundational fiction of travelling merchants is essential to its adumbration of an international legal perspective from which to articulate Scottish nationhood. This is not the supranational jurisdiction of the papal curia, but of ius gentium, an emergent space of adjudication between national jurisdictions that was, as Christopher Warren has shown, manifesting itself in the hybrid literary-legal forms of early modernity.Footnote 108 With striking power, the dialogue’s opening locates the question of national feeling – national shame, national pride – within an international debate on the question of the justice or otherwise of the war. It opens with a Scottish merchant, travelling through France, asking an English-speaking stranger where he is heading, with a view to having company along the road. The Englishman immediately taunts him, is he not ‘eschame’ (ashamed) to be called a Scot these days? The Scot replies with surprise that he does not know why he should be ‘eschamit’ of his ‘natioun’. Because, the Englishman mocks, his ‘natioun’ has been roundly humiliated and beaten in the present war. The Scot is unabashed: God may, he says, bring the Scots better expertise in warfare, but nothing can alter the fact that ‘all vnaffectionat men’, whether they be Scots, French or Dutch, think this present war is ‘uniust’.Footnote 109 While God may adjudicate the contingencies of war, the salient question of the war’s justice is to be debated between nations. And, by implication, national shame attaches not to those who lose a war, but to those who perpetrate war unjustly.

Lamb forgets to sustain this fiction of this commercial journey through France with any verisimilitude: the merchants arrive twice at Rouen and debating the second half of Henry’s Declaration only gets them as far as Paris. In further, surreal twist, three illustrious Catholic victims of Henry’s tyranny – Thomas More, John Fisher and Richard Reynolds of the Brigittine monastery of Syon – suddenly appear on the scene (speaking Latin) and agree (though dead) to judge the dispute. Nevertheless, the fictional setting of international trade is essential to Lamb’s conception of a how a legal and moral challenge to English invasion should be mounted. Throughout the war, the English proceeded in international diplomacy as if Scotland were not a nation; the French, for example, negotiating peace with Henry in 1546 (the Treaty of Camp) wished to have the Scots signatories to the treaty, but Henry refused, saying Scotland was a wholly English concern.Footnote 110 Mary of Hungary, governor of the Netherlands, consistently insisted that the Dutch had no quarrel with the Scots. She deeply regretted Charles V’s capitulation to war with the Scots at Henry VIII’s request, as, later, did Charles himself. A six-year-long state of war between the Dutch and the Scots, which neither side wanted, cost the Netherlands dearly in lost Scots-Dutch trade.Footnote 111 Lamb’s establishment of European trade routes as the setting for an Anglo-Scots debate on the justice of the war offers a startling shift of jurisdictional perspective from that of England’s insular, genealogical fiction of continuous feudal tenure. It is, quite simply, a perspective in which Scotland is assumed to be a nation.

Attention to this international perspective surfaces throughout the dialogue, exposing the imperialist ambition veiled by Henry’s rhetoric of disavowal. The English merchant solemnly rehearses Henry’s grief at the disrespect shown to him by his Scottish nephew.Footnote 112 He repeats practically verbatim Henry VIII’s complaints against James, including the missed York appointment, the harbouring of English Catholics and the retention of insignificant border lands. The Scot shrewdly counters by invoking the topics of circumstance (time and manner) to infer Henry’s intentions. Henry’s game, as we saw, was to make a virtue of denying intention to possess Scotland. Lamb’s probable inferences expose the mendacity of Henry’s game with dramatic or even novelistic effect: James’s alleged ‘contempt’ in absenting himself from York emerges as a prudent avoidance of recruitment into the service of Henry’s expansionist interests.Footnote 113

As to James’s harbouring of English Catholic ‘rebels’, these were, Lamb’s Scotsman says, hardly dangerous political dissidents: five or six old mendicant friars who, having entered sanctuary, could not be legally removed – here the Scot recognises jurisdictional plurality and the autonomy of ecclesiastical law (sanctuary in England had been abolished at the Reformation).Footnote 114 Finally, on the question of the border land alleged by Henry to have been usurped by the Scots, and of no great value, Lamb’s Scottish merchant was openly scornful. When evidence is in doubt, there should always, in law, be two litigating parties and a judge, he insists: ‘suld your kyng haue bene partie and also juge in his awin causs?’, he asks. More importantly, even had the land been proved to have belonged to England, ‘suld your kyng haue mouit so haistie crewell weir for ane thing of so sobir valour, quhilk als wes nocht challangit ij.c yeiris [two hundred years] befor that tyme?’. He cites a legal maxim, taken from Proverbs 18.1 in the Vulgate: ‘He who seeks to abandon a friend, looks for opportunities.’Footnote 115 In fussing over some acres of the debateable lands that no one had cared to claim for the last two hundred years, Henry is clearly scraping the justificatory barrel for causes of international war. Indeed, this question of respecting jurisdictions (for the Anglo-Scots Marches had their own courts to decide such issues) epitomises Lamb’s larger point about using the Declaration as a judicial decision about war. The justice of an invasive war cannot be decided within a country’s own common law, but only within ius gentium, the law of nations. Can it be right, the Scot asks, that in a great, weighty and doubtful question of war between two ‘potent realmes’, one country’s own national law should conclude and define the question?Footnote 116 As Henry respects neither spiritual nor border jurisdictions, so, argues Lamb, he wrongly imagines that an international legal question of the justice of war can be defined by English common law and decided by a court (Parliament) in London. This is a question we will return to in Chapter 6 on English history plays.

Lamb’s Resonyng deftly exposed the absurdity of Henry’s argument that James V had done him injuries enough to justify war. Arguing effectively against the Declaration’s second half was harder because its credibility relied on archival evidence, on the existence of documents and charters. Lamb, however, engaged in no Scottish counter-mythology. To the English merchant’s querying his opinion of the ‘probabilite’ of the Declaration’s story of English ‘superiorite from the first habitatioun of Albion’ through the story of Brutus, Lamb’s Scot replies that origins of peoples are so uncertain that ‘vpone sic a ground ye may devyd this ile and beild sic probabilitie as ye lyk imagine’. To the rest of the historical argument – the homages gathered by Cuthbert Tunstall from John of Caen’s Great Roll and Hardyng forgeries – Lamb’s response, as his editor, Roderick Lyall observes, was simple but inspired: to follow Polydore Virgil, ‘scarcely a witness who can be charged by the English with pro-Scottish bias’.Footnote 117