“From this point on, we were members of the family of hundreds of millions of democratic women of the world”, concludes Boris Fái, one of the leaders of the communist Hungarian women's movement, her account about the first Women's International Democratic Federation (WIDF) congress of socialist women from all over the world, which took place in Paris in 1945.Footnote 1 The time between the immediate aftermath of World War II and the establishment of a single-party communist regime in 1949 was a phase full of hope, fascination, transformation, solidarity, and betrayal for the Hungarian women's movement. The freshly founded women's organization, the Magyar Nők Demokratikus Szövetsége (the Hungarian Women's Democratic Federation, MNDSz), which joined the WIDF, played a crucial role in channelling the Hungarian women's movement into one strand of international women's rights. This article analyses the role internationalism and women's solidarity played in Asszonyok (Women),Footnote 2 the main public forum of the politics of the MNDSz, which also served as a platform of women's political education and of public representation of a new form of female internationalism. Despite the almost complete lack of other published sources on women's rights from this time, the magazine has not been researched in detail until now.Footnote 3 Between 1945 and 1949, Hungary experienced a transition to democracy and then to Stalinism, while the MNDSz, first a popular front umbrella organization, became by 1949 the women's section of the Magyar Kommunista Párt (Hungarian Communist Party, MKP). I explore this process through five years of Asszonyok, focusing on reports about big international meetings on the one hand, and reports and correspondences about bilateral relations with women and their organizations from other countries on the other hand. In particular, with a combined approach of social and intellectual history, the article analyses the sidelining of pre-war feminism by the communist Hungarian women's movement after World War II, as well as tensions between the emerging discourse of socialist internationalism and notions of race and racism.

Despite initially serving as the voice of the popular front women's movement, Asszonyok was predominantly edited and written by communist women. It documented the political and social processes of the time, but its role went way beyond creating a communist women's sensibility. While it served as a propaganda tool, it was also a platform of debates about women's rights, where arguments about the desired form of women's emancipation took shape. Women's rights were scarcely discussed elsewhere in the main intellectual forums of the time. For example, the most important social science journal of the time, Társadalmi Szemle (Social Science Review) did not have a single article about women between 1946 and 1949, and only a handful were written by women. This makes Asszonyok an indispensable source that should be researched systematically in order to understand the processes by which the discourse on women's rights changed in the immediate post-war era.

The five years when Asszonyok was published were formative for the socialist women's emancipation discourse, and this is well documented in the magazine. The editors of the magazine, as well as the women in the MNDSz, debated fiercely with the anti-fascist, yet in several aspects conservative, Christian Women's League on issues such as divorce, the rights of children born out of wedlock, women's role in society, and the conflict between women's employment and women's traditional role within the family. The relationship with the feminists of the pre-war Feministák Egyesülete (Association of Feminists; FE), who were fighting not only for women's suffrage, but also for labour and education rights, and were taking a stance on issues such as prostitution, trafficking, and illegitimacy, was more ambivalent owing to the similarities in the political demands between socialist women and the feminists. These shared interests did not prevent them from having severe clashes over the years, however.Footnote 4 In 1912, the FE accepted new legislation that expanded suffrage to women with limitations according to educational and property criteria; this created an irreversible abyss between feminists and social democrats.Footnote 5

First marginalized and then forced into illegality during the Horthy regime (1920–1944), the FE was re-established in 1945, but dissolved in 1949. Attempts by the FE to find a place in relevant and visible public forums such as Asszonyok were largely ignored by the MNDSz,Footnote 6 and their ideas of solidarity among women were quickly marginalized by the communist women's agenda of women's class- and work-based emancipation. In light of the complicated history of socialist and feminist women, a story that started in the early twentieth century and continued in the aftermath of World War II, I will rely here on a clear distinction between feminism and socialist women's emancipation politics as two separate strands of political thought. Although the communist women's goal was to address all women, they prioritized class and loyalty to Marxism-Leninism over gender alliances, and clearly distanced themselves from feminism. They either treated the history of the FE as the past, acknowledging some of its merits,Footnote 7 or were opposed to feminism as the ideology responsible for creating a gender cleavage that carried the danger of breaking up the class struggle.Footnote 8 Socialist women's emancipation politics introduced substantial changes in women's lives, and the history of the women and women's organizations working for these changes deserves to be thoroughly researched and discussed. However, I suggest using the term “feminism” for individuals and groups who embraced this label and will refer to the women in the MNDSz as communist and socialist women, and their politics as socialist women's emancipation politics. I therefore diverge from the term “left feminism” recently suggested by Francisca de Haan and others for the activities of communist women in Eastern and East Central Europe, while acknowledging the merits of their research in re-evaluating the complexities of women's lives in this part of the world during state socialism.Footnote 9 By this move, I am also hoping to divert discussions from the directions set by recent debates and the struggle over heavily contested concepts such as agency.Footnote 10

THE MNDSz AND ASSZONYOK

After the years of illegality, the immediate post-war period carried the promise of democratization and thus was a fascinatingly ambiguous time for the women's movement.Footnote 11 The MNDSz was founded in 1945 and by 1949 became the only women's organization in the country.Footnote 12 Its founders were women from the illegal communist movement, but their aim was to recruit as many women as possible, in the spirit of the “coalition era”.Footnote 13 As the leadership of the organization described their objectives to the MKP leadership in April 1945, the goal was “to gather all women into one organization, no matter what social status, party affiliation, profession, religion, all the women and girls who love their country and want to work”. It is important to note here that women's “willingness to work” already carried a heavy political weight. It meant much more than simply taking up employment, it meant the willingness to embrace the values of socialism, as debates about “bourgeois women”, prostituted women, or the Roma show. At the same time, as the letter to the party leadership continues, “in order to be able to fulfil the programme of our Association, we need to implement a comprehensive programme of women's education, and for that, we indispensably need a centrally controlled magazine that covers the entire country to present our work for society and women's (political) education”.Footnote 14 A letter from a year later is more explicit about the kind of political education that is to be expected from the MNDSz: one “in the spirit of the party, but without its terminology”, wrote Magda Aranyossi, the editor in chief of Asszonyok.Footnote 15

The activities of the MNDSz were becoming more systemic over time. In Boris Fái's retrospective account (probably from the 1960s), the work of the MNDSz had three directions, focusing on healthcare and social issues, cultural activities, and politically enlightening educative work.Footnote 16 The communist women in the MNDSz were aligned with the MKP agenda, but had their own ideas and preferences driven by their personal knowledge “from the field”. They were the ones working with women from all walks of life and were aware of their needs as well as the possibilities to recruit them to the communist cause. One article about the organization locates the 1946 congress of the MNDSz as the moment when the organization became more “politicized”, in other words more explicitly performing MKP ideology.Footnote 17 There were several rounds of power transfer within the organization, though. As a result of these, the intellectual women who founded both the MNDSz and Asszonyok disappeared from the leadership, and by 1952, all MNDSz activities were subordinated to the trade unions.Footnote 18 In 1948, all other women's organizations were abolished or merged into the MNDSz. Moreover, progress on the organizational level necessarily affected the ideological level as well, as the women's rights discourse and politics was dominated by the communist women. These changes were directly reflected in Asszonyok, the editorial team and the content of the magazine following the changes within the MNDSz.

ASSZONYOK AND THE WOMEN BEHIND IT

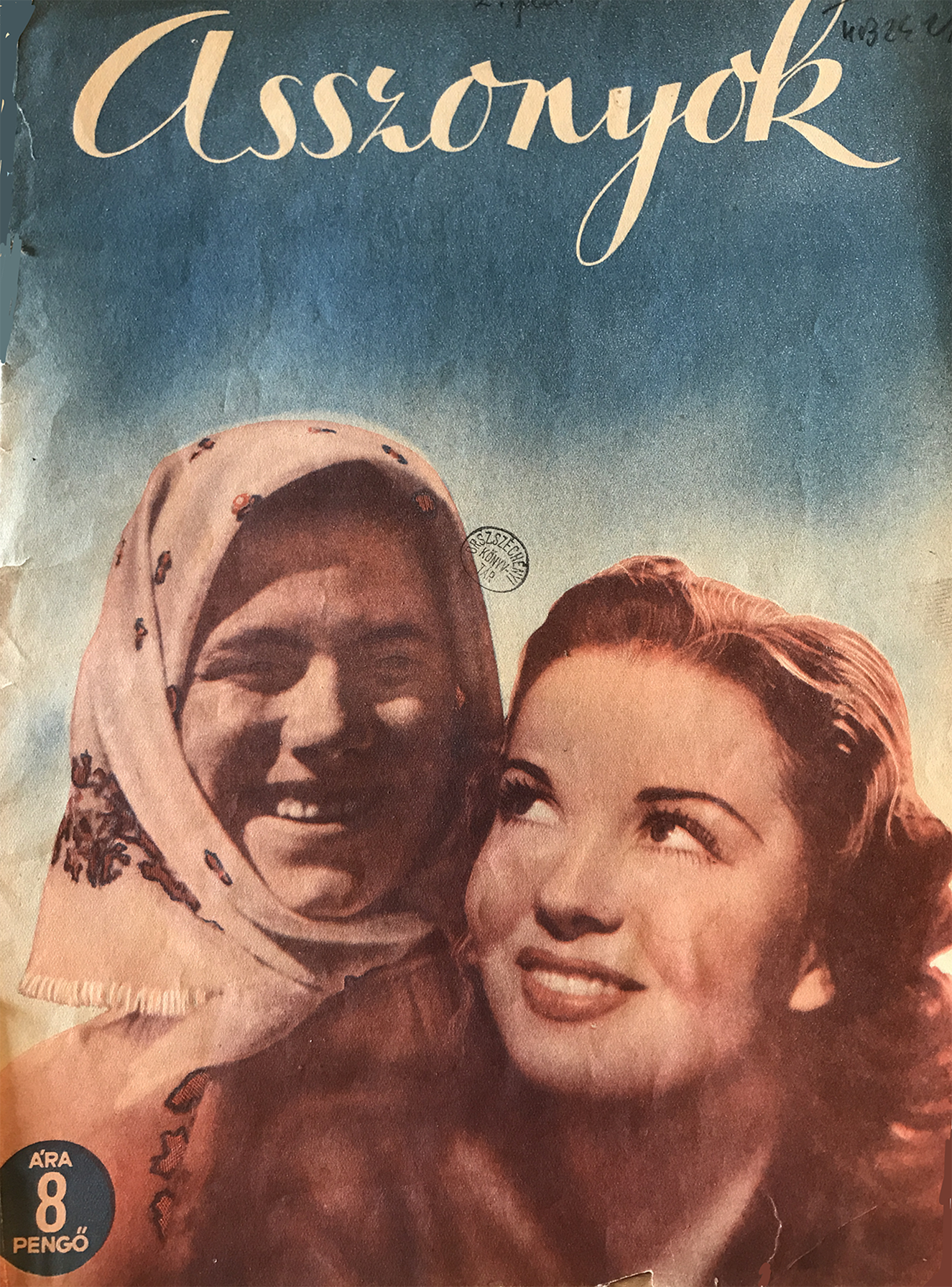

Asszonyok, published first in the summer of 1945, was created by a couple of fascinating women, and was heavily shaped by a range of inter- and transnational transfers. A few years later, in 1949, when the MKP solidified its power, it was transformed into Nők Lapja (Women's List), a magazine still published today. The first issue of Asszonyok was printed in June 1945 on paper given to the women's movement by Marshall Klementin Voroshilov, the president of the Allied Control Commission in Hungary at the time (Figure 1).Footnote 19 From the outset, Asszonyok took on the highly ambitious task of politically educating women, without creating the impression that they were being targeted by propaganda. In common with many women's magazines, Asszonyok taught women about hygiene, efficient household practices, and new principles of childrearing (the latter from a rather progressive viewpoint, for the time). These themes were accompanied by articles focusing on political and social education, and these included stories about women all over the world.

Figure 1. The cover of the first issue of Asszonyok, published in June 1945.

Among the MNDSz women most involved in creating the magazine were Magda Aranyossi and Boris Fái. While Fái was one of the main organizers of the MNDSz and the magazine, she and her fellow activists heavily relied on the intellectual input from Aranyossi (who soon became the editor-in-chief of the magazine), as well as the protection and influence of the wives of prominent communists, such as Júlia Rajk, the wife of the future minister of interior and creator of the state secret police, László Rajk,Footnote 20 and Lili Révai, the wife of the cultural and intellectual ideologue of the MKP, József Révai. Fái and Aranyossi took different paths to the Communist Party. Fái was born into a middle-class family in Budapest. She was engaged in women's mobilization from an early age, having participated in the work of the FE with her mother. While, over time, she embraced communism and a class-based emancipation politics over the rights focus of the FE, organizing women for the MKP evoked memories of working with her mother in the FE.Footnote 21 Fái never disavowed her mother's feminist past, but treated it as the politics of the past, whereas communism was the future, the movement that had the potential to mobilize and emancipate masses of women – workers, peasants, bourgeois alike. As she wrote in her memoir: “Already during the time in France, in emigration, and then right before the liberation and during the siege, I was preparing to work for the women's movement.”Footnote 22 On both occasions when Fái publicly talked about her ideas of women's politics, in the 1945–1949 period, and in her published recollections of the time in the 1960s, her ideas of women's emancipation always embraced all women and emphasized the importance of inter-class reconciliation.Footnote 23

Magda Aranyossi, a writer and journalist, like many Hungarian communists spent most of the interwar period in emigration in Germany and France. In Paris, she ended up working for the magazine Femmes. Having come from a Jewish landowning family, Aranyossi had a solid bourgeois education and familiarized herself with Marxism after having met her husband, Pál Aranyossi. In France, she first worked as a typesetter for the newspaper of the Hungarian workers in Paris, Párisi Munkás (Parisian Worker). As she noted later: “This work turned out to be unexpectedly useful for me […] this was when traits of my old, bourgeois mindset were shattered by the simple wisdom of the workers’ letters.”Footnote 24 Before her time at Femmes, she had been the editor of the newspaper for the women in the Hungarian workers’ emigration with the title Március 8 (8 March). Her husband already worked for the prestigious Regards (the editorial board of which included Romain Rolland, Maxim Gorky, André Gide, and Isaak Babel, among others).Footnote 25 The illustrated weekly clearly influenced Magda Aranyossi's conception of a politically educational women's magazine, and thus her work with Femmes and later with Asszonyok.

During her time at the Confédération générale du travail unitaire and in the French communist women's movement, Aranyossi became acquainted with Bernadette Cattanéo and Gabrielle Duchêne, and closely followed the creation of the fellow organization of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, the Comité mondial des femmes contre la guerre et la fascism (World Committee of Women Against War and Fascism; CMF) in 1934. This is when she got to meet, for the first time, Dolores Ibárruri (Pasionaria), who became a major supporter of the MNDSz in the WIDF. Aranyossi was a hands-on editor and organizer, with stylistic skills and vision, so she was quickly recruited to work for the new magazine Femmes (original title: Femmes dans l'action mondiale, published between 1934 and 1939, twenty-five issues in total).Footnote 26 Femmes was the journal of the CMF and generally envisioned the women's movement as international. The other source of inspiration for the profile of Femmes, besides Regards, was the Soviet magazine Rabotnitsa (The Woman Worker, first published in 1914).Footnote 27 The result was a combination of political education (and propaganda) with a large amount of visual material, and articles about traditional themes of women's magazines.

Aranyossi remembered her debates with Cattanéo and the French leadership over more representation of women from the colonies, as well as more controversial issues concerning women's rights, such as abortion. The French women considered the former less relevant, whilst the latter was much too risky in France in the mid-1930s. Aranyossi was willing to risk public outrage and felt that the women from the colonies deserved more attention, whereas the French socialist women had other priorities: “Only later did I realize that Cattanéo's resignation from not only the colonial, but also some other questions, was more than simple naïveté. They did not know history well, had childish illusions of the future, but were all the better in navigating the daily issues.”Footnote 28 She was impressed by how quickly they reacted to domestic politics, with their ability to organize mass protests within hours. The knowledge Aranyossi acquired clearly shaped her view on the creation of Asszonyok.

During the five years of its short existence, Asszonyok went through several transformations, most of which followed the power dynamics and political programme within the MNDSz. The profile of Asszonyok was new to Hungarian readers: the earlier illustrated women's magazines targeted middle-class and wealthier women, while the political ones, such as the FE's A Nő és a Társadalom (Woman and Society – later simply A Nő) and the journal of the social democratic women, Nőmunkás (Woman Worker), were without attractive illustrations. The innovative and experimental concept of Asszonyok was also far from set in stone. After an ambitious start in 1945, the concept of the magazine became subject to debates within the MNDSz. These debates led to its refashioning in 1946, and while Aranyossi remained in charge, those in the MNDSz leadership with close ties to the MKP wanted more political and professional control, including every issue to be approved by two women from the MNDSz leadership.

Lili Révai, who was in the MNDSz leadership at the time, complained to the MKP Central Secretariat that “[u]ntil this time, the paper was full of rather uninteresting content, it was insignificant, not even adequately reporting about the work of the MNDSz”. She did not blame Aranyossi directly, admitting that the editor-in-chief was doing the work of an entire editorial board by herself. However, relieving Aranyossi's workload was a way to intervene in the internal affairs in the magazine. Révai was against “the original picture magazine format, which we find incompatible with the changes of the inside content”.Footnote 29 Révai wanted more political propaganda, while Aranyossi believed in a more cautious and indirect approach. When the publication ceased for a few months owing to the economic difficulties created by massive inflation, Révai took her chance to implement changes. Nevertheless, the magazine eventually retained its picture magazine format, and by the autumn of 1946, a new editorial board was established on which all women were MKP members, Aranyossi remaining editor-in-chief. In her letter to the MKP, Aranyossi presented the ambitious plan to reach the print run of 50.000 copies per issue and her strategy to edit Asszonyok “in the spirit of the party, but without its terminology”.Footnote 30

Part of Aranyossi's plan was an entire section with focus on the “whole wide world”, where also the “Soviet section” would find its place. Apart from this section, several types of articles reported on international affairs: original texts written by an editor, journalist, or activist working for the magazine, and materials received from the Soviet Union. While it is clearly noted in Nők Lapja (the successor of Asszonyok) that it reprinted materials from the Soviet magazine founded in 1945, Soviet Woman, this was often the uncredited source in Asszonyok too. On other occasions, materials sent directly by the Antifashistskii Komitet Sovetskikh Zhenshchin (Soviet Women's Anti-Fascist Committee, AKSZh) were used.Footnote 31 Soviet Woman was edited by the AKSZh, led by Nina Popova.Footnote 32 The magazine “was an artifact of both wartime internationalism and Cold War competition”, and over time, it was widely distributed in multiple languages (Russian, English, French, and German, as well as in Hindi, Japanese, and Spanish).Footnote 33 Its Hungarian edition first appeared in 1960 with the title Lányok, Asszonyok (Girls, Women) and between 1960 and 1972 again as Asszonyok. This magazine was the translation of the Soviet edition, and it never reached the popularity of its contemporary local counterpart, Nők Lapja.

It needs to be emphasized that as a journalistic and political endeavour Asszonyok was more deeply rooted in the context of Hungarian women's movements and women's interwar communist activism, especially Aranyossi's work at Femmes. In this sense, it is very much a product of the 1945–1949 era, documenting the influence of interwar intellectual traditions as well as the transition to the Sovietized one-party state. Its title itself tells this story. The words femmes and women (as well as женщины/zhenshchiny) can be translated both as “asszonyok” and as “nők”. The more inclusive one, nő (plural: nők), was used as the title of the journal of the FE. It was all the more fitting, since the word nő highlights women's individuality, while the word asszony (plural: asszonyok) refers to married women (and to some extent more widely to mature women). At this point, the focus on the individual woman that characterized feminism in the first half of the twentieth century belonged to the past, and even though the MNDSz activists were divided in their relationship to the FE, many acknowledging its merits,Footnote 34 an impression of being the carriers of the feminist heritage had to be avoided. The reference to marriage in the term asszony, while it excludes young women, suggests respectability. This was in line with Asszonyok targeting the broad population, with its primary mission to win masses of rural working women and women workers, first, for the cause of post-war reconstruction, and secondly and less openly, for the communist cause.

INTERNATIONALISM, RACE, THE MNDSz, AND ASSZONYOK

For the women in the MNDSz, one of the clearest symbols of internationalism was the newly founded WIDF.Footnote 35 It was this level of international politics and diplomacy on the one hand, and bilateral connections (which often grew out of the involvement with the WIDF) on the other hand that most influenced the meanings of internationalism of the MNDSz and Asszonyok. In her memoirs written in 1970, Boris Fái remembers receiving the invitation to the 1945 congress of the WIDF in Paris. The document reveals several aspects of how internationalism mattered to the local women's movement:

I felt this enormous excitement. Not only because apart from our contact with the Yugoslav and Romanian women, this was our first contact with abroad [a külfölddel]. We didn't know much about the women's movements elsewhere, since there was no train or mail connection yet. We realized it now, from the brochure sent with the invitation, that there are women from America, China, Vietnam, Italy, […] who fight for the same goals, and with similar means as we do. That women of the whole world fight for democracy, peace, the protection and happiness of children. Then we saw that we were on the right path. […] It was a delegation of ten women. All four parties had representation. […] From this point on, we were members of the family of hundreds of millions of democratic women of the world.Footnote 36

Joining the WIDF and having access to the most memorable figures of the socialist women's movement worldwide was a huge step not only because of Hungary's role in World War II. Fái, Rajk, and Aranyossi all knew about life during decades of illegality, and, Fái especially, imprisonment and torture too. Being part of the WIDF congress meant an acknowledgement of their views and work in front of what seemed to them like the entire world.

The third aspect of internationalism, beyond symbolizing a clean slate after the war as well as the realization of the principles of socialism, was that of worldwide solidarity among women. Asszonyok's task was to ensure that all these aspects were duly explained to Hungarian women. Articles on the subject varied between reports about the WIDF; reportage on women's lives in other, mainly socialist countries; women in socialist parties and workers’ movements elsewhere; and portraits of women activists from all over the world. Anti-imperialism and anti-colonialism were already an integral part of women's socialist internationalism at this early stage. Central European women, who had previously had very little contact with the developing world/Third World, were fascinated but also generally uninformed.Footnote 37 Fái's first impression from the WIDF meeting in 1945 summarizes the good intentions as well as the lack of knowledge that was hard to overcome and often stood in the way of anti-racism and transnational solidarity:

Thousands of women from forty countries gathered there, and many of them came from much further away and often on much more arduous journeys than us. We found here the crème-de-la-crème of the women of the world. We did not even understand the language of most of them, still, there was a strong tie between all of us from the first moment. We were very, very different [from each other]. Not only our language, our skin colour, our clothes, our customs. There were rich and poor, highly educated and very simple women. But most of us had lived through the war, many of us the hell of prisons and concentration camps, we all hated fascism and were ready to fight for peace, independence, democracy.Footnote 38

This sense of solidarity was the basis of their internationalism, stemming from the shared struggle against fascism and for a socialist future. Political alliances overrode other factors, such as class and race, even though class was recurringly evoked as a reason for exclusion. When talking about women in general, the MNDSz and Asszonyok claimed that all women would be liberated by the movement. Still, it becomes apparent from articles about women in particular life situations or as members of ethnic, national, socio-economic groups that the women who deserved sympathy and rights were those with the correct political views.

Encountering women of colour in the WIDF reveals several aspects of the complicated treatment of race in socialist theory, including the still defining work of Marx and Engels. Anti-imperialism and anti-colonialism were integral elements of the Marxism-Leninism that guided the new communist leaders in East Central Europe after World War II, and this greatly influenced their anti-racist agenda. For the USSR, differentiating its policies in Soviet Asia from the colonialism of the Russian Empire was essential for its self-identity and legitimacy; racial, ethnic, and cultural differences were a key terrain for this.Footnote 39 This approach extended to the developing world/Third World and the national struggles for independence and socialism. In 1945–1949 we cannot talk about “global communism”, but alliances such as the WIDF were important first steps towards what soon became global communism.Footnote 40 The politics of anti-imperialism in this Cold War global setting was struggling with its language of anti-racism. This was before the “linguistic turn” of the language of anti-racism, and since the language of anti-racism we use today was born to the west of the Iron Curtain with the 1960s civil rights movements, it remained foreign in the “Second World” for quite some time. The language of Marxism-Leninism, starting with Marx and Engels, was influenced by nineteenth-century theories of race too. This, as Erik van Ree argues in his analysis, deserves a nuanced evaluation in its contemporary context. He concludes that though Marx and Engels can be read as racist today, they also relied on “the Lamarckian proposition of circumstance remoulding heredity”,Footnote 41 and thus did not treat racial traits as unchangeable. This ambiguity nevertheless accompanies the concept of race in the period of state socialism.

While scholarship about socialist East and East Central Europe has avoided taking race as a focus of analysis in the region seriously for a long time, as Catherine Baker in her book about race and Yugoslavia emphasized, it is an unsustainable notion that “eastern Europe could have entered the twenty-first century without exposure to the global dynamics of race”.Footnote 42 This becomes apparent when we read how contributors to Asszonyok struggled to talk about race in the immediate aftermath of the war, and the political agenda and political uses of anti-fascism of the time. In fact, internationalism in Asszonyok was closely tied with presenting and talking about women from the Global South, and the visible difference of these women had to be tackled in the texts. Lacking a reflective discourse about race, many of the articles, to quote Baker again, “contained a hierarchy of biological and cultural essentialism that did resemble race”.Footnote 43 These hierarchies appear in the discourse about the local Roma population, even when on paper the situation of the Roma in the early period of state socialism was framed as a problem of work and class.Footnote 44

SOCIALIST FRIENDSHIPS AND BETRAYALS

The very first issue of Asszonyok opened with the news that the MNDSz had been invited by Yugoslav women to the first post-World War II meeting of anti-fascist women (Figure 2).Footnote 45 This was followed by reports on the WIDF meetings, including those introducing the most charismatic women in the organization, as well as reports and portraits of women from neighbouring countries. Other reports about the international belonging of the Hungarian women's movement were written by activists and journalists visiting the countries in the region. The tone in these articles is much more personal and subjective, and the metaphor of friendship ties them all together. A new, political concept of female friendship is emerging at the time, also shaped by the Soviet “friendship of the peoples” campaign, which began in the USSR in the 1930s and was gradually entering East Central Europe in the aftermath of World War II.Footnote 46 The friendship rhetoric was crucial in distancing the USSR's international politics (and its treatment of Soviet Central Asia) from earlier imperial practices.

Figure 2. The article about the first visit to the partisan women in Belgrade in 1945, “Nőkongresszus Belgrádban” [Women's Congress in Belgrade], Asszonyok, 1:1 (June 1945), n.p.

The letter from Dolores Ibárruri, in which she addresses Anna Kara and Boris Fái as her “dear [female] friends” was published in large script and placed prominently in the magazine, despite its otherwise uninteresting content. What mattered was the declaration of friendship.Footnote 47 The intimacy associated with friendship, and especially female friendship, was meant to bring the movement and women from all over the world closer to the readers.Footnote 48 When it came to the most famous women from the international socialist movement, Asszonyok approached Ibárruri, Nadezhda Popova, Eugenie Cotton, and Anna Pauker with admiration and a sense of inferiority: in contrast to them, Hungarian women “had nothing to say about the fight against fascism”.Footnote 49 The support of these iconic women was a form of rehabilitation of the country itself. Ibárruri argued for inviting Hungarian women to the Executive Committee of the WIDF: “Because the Hungarian people are not identical with the Horthy and Szálasi fascists, because the real Hungarian people is the one whose heroic sons were fighting in Spain, many of them sacrificing their lives for the Spanish freedom.”Footnote 50 These are Fái's words, narrating Ibárruri's statement, reflecting again on the sensitive matter of “the last satellite” status of the country. As a result of this admiration, Ibárruri and other women from the WIDF were presented similarly to film and theatre stars. Asszonyok proudly announced that women in the MNDSz had earned the respect of their comrades in WIDF for contributing to the maintenance of peace and democracy in Hungary.Footnote 51 The next year, in 1948, the country even hosted the next WIDF congress.Footnote 52

The celebration of friendship and a broad anti-fascist alliance of women is in strong contrast with the series of betrayals in the Stalinization process among the charismatic women of the era. Andrea Pető writes about the role of Boris Fái in attesting against Júlia and László Rajk, family friends of Fái and her husband, during the Stalinist show trial against László Rajk.Footnote 53 In line with the verdict of the trial, Rajk was executed on 15 October 1949. Asszonyok's international reporting accidentally published an image that can be read as a symbol of these betrayals, portraying three women, among them the Czech feminist lawyer Miládá Horáková (1901–1950). Horáková was one of the most important feminist thinkers of the interwar period not only in Czechoslovakia but in East Central Europe, who over the course of a couple of years changed from an anti-fascist hero into an enemy of the state.Footnote 54 In the issue of Asszonyok from 1947, Horáková was presented as a member of the Czechoslovak delegation of the WIDF leadership.Footnote 55 The picture of the women from Czechoslovakia is included in photo reportage about “women of the wide world”, republishing pictures from the 1945 WIDF meeting. Miládá Horáková is in the company of Marie Trojanová and Anežka Hodinová-Spurná. The accompanying script has several inaccuracies: the names of all three women are misspelled and their party affiliations are mixed up. Ironically, Horáková was presented as the communist representative and Hodniková as the one from the Czech National Social Party, Horáková's moderate social democratic party. There was indeed cooperation between the different women's organizations at the time, but while Horáková was executed in the first show trial in 1950, Hodinová had a steady career in the party, including leadership of the Committee of Czechoslovak Women.Footnote 56

The most likely reason for the inaccuracies in this article is errors in the transliteration of Cyrillic script that appeared in the Russian materials that were reprinted. These inaccuracies document the scarcity of information and resources of the almost naively enthusiastic MNDSz women. The picture was important for the mission of the MNDSz as it embodied two of the most politically important messages of the time: broad party coalition (popular front-like) politics and female friendship, symbolizing women's solidarity and implying a higher level of intimacy. The case of the picture of the three Czechoslovak women allows us a glimpse into the chaotic ways in which Hungarian women were immersed in international politics on a scale not seen before. With multiple political agendas in the background, similar processes were taking place everywhere in East Central Europe: popular front women's organizations joined the WIDF, including women who would later disappear (emigrate, get imprisoned, or simply be sidelined). However, at this point, the stories about women “from all over the world” sent a political message to working-class and peasant women all over the country.

BILATERAL RELATIONS: REGIONAL FRIENDSHIPS, RACE, AND RELIGION FROM A DISTANCE

In 1947, Júlia Rajk, first secretary of the MNDSz, wrote upon meeting Josip Broz Tito: “we will prove it through our work that we are worthy of this friendship”.Footnote 57 Yugoslavia, a country proud of its partisan resistance to fascism, was, along with the Soviet Union, admired by the MNDSz women. Articles in Asszonyok celebrated the partisan movement, speaking highly of the achievements of the (Antifašistička fronta žena (Women's Anti-Fascist Front, AFŽ) and the social transformation taking place as the result of their work. The short articles discussed a broad scale of social issues, with an undercurrent of a domestic political programme that targeted Hungarian women.

Presenting women in the Yugoslav partisan movement to a broad, still rather traditionally minded audience about women's roles required a balance.Footnote 58 It was to be shown that even amid fighting and winning a war, these celebrated women did not abandon their traditional gender roles. Beyond the broader readership of Asszonyok, the MKP was also not willing to drastically subvert the existing patriarchal relations. Thus, instead of emancipation from traditional gender roles, partisan experience was presented as a means to eliminate women's socio-economic inferiority, while they could retain their traditional feminine roles as mothers and wives. In the spirit of recruiting women across classes, there were reports about bourgeois women who joined the partisans and, through the experience of camaraderie, became supporters of the Tito regime.Footnote 59 The sense of camaraderie was even more deeply rooted in the experience of all women being mothers, daughters, and sisters of men who sacrificed their lives in the war: “And we saw the real mothers in them, the ones who worry about their children smartly and who know how to act. The congress of the anti-fascist women of Yugoslavia was nothing but the congregation of smart mothers.”Footnote 60

The idea of peace itself was closely entangled with the possibility of women returning to their traditional roles. The article about a Hungarian woman joining the Yugoslav and Polish partisans emphasized: “As good a soldier she was, she is a good mother now.”Footnote 61 At the same time, the MNDSz women appreciated that in Poland and Yugoslavia, where a large number of women were active in the war, women had higher positions in politics; they even held ministerial seats.Footnote 62 These international comparisons were made rarely, but allow for criticism of the current domestic situation, such as in a report on Poland: “Here [in Hungary] they don't allow women into such high positions, and I'm not saying it's because of male jealousy, but not all women get into the positions they deserve.”Footnote 63 Connecting women's political advancement to prior achievements enabled talk about the lack of women in powerful political positions in Hungary. The article about Poland suggests that the lack of a significant partisan movement in Hungary should not be a reason to exclude women from political leadership.

Beyond the broad subjects of female participation in partisan struggles and its gendered consequences, the reports portraying bits and pieces of the lives of women and children involved a combination of the themes of friendship and race, women's rights, and prostitution. Work, as the most important concept for communist politics after 1945, tied women's rights, prostitution, and poverty together. The magazine reports presented Yugoslavia as a country where even the problem of beggars and prostitution had been solved by the high demand for labour.Footnote 64 In an article by Nóra Aradi (later an art historian), prostitution is not seen a matter of sexual morale, but much rather as a result of poverty (symbolized by “begging”). At the same time, the idealization of retraining prostituted women into a “useful labour force” already carried the danger of restigmatizing prostitution by placing it into a moralistic framework from the socio-economic one. In later years of state socialism, women in prostitution were again labelled asocial and amoral, as according to the official stance, the “forgivable” reason of poverty had already been eliminated.Footnote 65

Children's well-being was a crucial barometer of the success of post-war reconstruction, and a new approach to pedagogy as well as attempts for socialized childcare accompanied the care for orphaned and sick children.Footnote 66 The newly built, modern pioneer city in Belgrade evoked admiration in the Asszonyok reports. However, the highlight of Yugoslav child protection policies was their approach to Roma children: “In Yugoslavia, There is No Child Beating, There are a Lot of Female Locomotive Drivers and the Gipsy Pre-Schoolers [sic] Want to Build Hungarian Train Tracks,” says one lengthy title.Footnote 67 Roma children signal the progress in Yugoslavia next to the image of women in traditionally male jobs of physical labour (the unfortunate yet widespread metaphor of socialist women's emancipation). Bidding farewell to the MNDSz delegation, “the black-eyed little ones, the children of ‘Tito's country’”, offer to build a railway for the Hungarian children.

In these first years of post-World-War-II socialist women's activism and Asszonyok, this was the first of the very few occasions when the Roma were mentioned. As Celia Donert shows us, the communist agenda for the Roma population in the immediate post-war phase was very much in the making.Footnote 68 However, already then, the acknowledgement of the Roma as fully fledged members of socialist society was tied to their participation in the labour force,Footnote 69 and the top-down emancipatory sentiments were accompanied with a discourse in which the Roma were depicted as innocent because they never supported fascism.Footnote 70 The innocence discourse, which was always tied to a romanticized ethnicization and infantilization, is what we find in this article too. While almost every issue of Asszonyok featured women of colour and their relationship to socialism, Romani women were missing. It seems that children (in another country) were innocent and exotic to allow for their mention, especially in light of the endearing story about the dialogue.

While Yugoslavia's ethnic, religious, and cultural diversity was celebrated as part of the new internationalism, the discussion of particular groups who stand out of the white, Christian/secular paradigm posed a challenge about the right kind of language in which they could be presented. Muslim women in Bosnia and Herzegovina were shown as the symbol of backwardness and target of top-down emancipation.Footnote 71 Their hijab was treated as the ultimate proof of this, especially in contrast to “the women of the AFŽ [who] instead of the veil, wear the 1941 star of the partisans. But the more progressed women do not look down on the retarded ones [another potential meaning: ‘on those who are left behind’ [visszamaradottak]”.Footnote 72

This kind of power hierarchy between emancipated, progressive women (women who were either educated owing to their background or received their education in the partisan movement) and “backward” women has a growing literature.Footnote 73 The appearance of Muslim women in the Hungarian context adds an extra layer, given the agenda of the Asszonyok editorial board of “lifting up” the backward women at home. Introducing the story of Muslim women in Yugoslavia to the Hungarian readers offered two life models: the “advanced” women of the AFŽ and those “left behind”, but being “helped” in their development. The readers could thus choose with whom to identify, and both choices would eventually feed into the emancipation process.

RACE AND RACISM

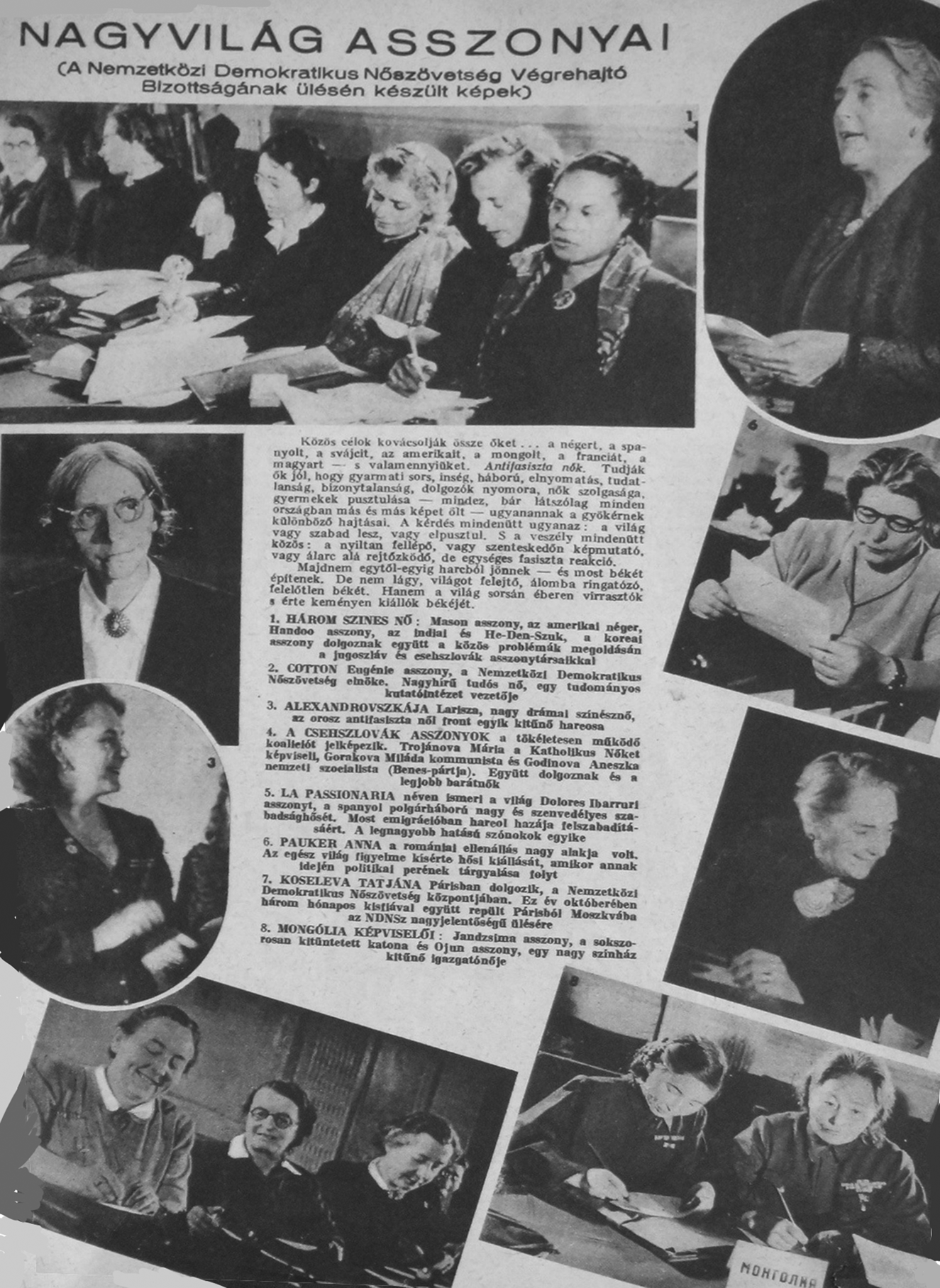

The bilateral encounters with Yugoslav and Polish women offer glimpses into the language of race and religious difference. The reports on the WIDF meetings are a rich source of language about race at the dawn of the era of global communism with its anti-racist agenda, a milestone in the complex and often troubled history of the concept of race in the history of socialist ideas. There is a difference in language and approach alike between the reports on individual countries and on the WIDF. In the latter, white women in leadership positions overshadow the women of colour around them, despite the wide presence of women from Africa, Asia, and the United States in group photos of the assemblies.Footnote 74 These photos are often accompanied by texts such as “colourful women”,Footnote 75 and “colourful company […] negro [sic], Hindu, Korean women delegates” (Figure 3).Footnote 76 The reader learns significantly less about the achievements of these women compared with the (mostly white) WIDF leadership and the women from various European partisan movements, and exceptionally, women from Central Asia representing the Soviet Union. The imbalance in the visual portrayal correlates with the language: women of colour, whether from the West or the Third World, are mostly not even mentioned by name, let alone by their position. The responsibility for this is not solely on the women in the editorial board of Asszonyok; even the reports from the Soviet materials perpetuated the inherent injustice.

Figure 3. “A nagyvilág asszonyai” [Women of the Wide World], Asszonyok, 3:1 (1 January 1947), n.p. Upper-left corner picture has the subtitle “1. Three colourful women: Mrs Mason, the American negro [sic], Mrs Handoo, the Indian lady, and Hŏ Chŏng-suk, the Korean lady cooperate to solve problems they have in common with their fellow Yugoslav and Czechoslovak women.’ Part of this photo was republished in 1947 (“Két esztendeje” [Two Years Ago], Asszonyok, 3:23 (1 December 1947)). Bottom-left corner: “4. The Czechoslovak women represent the perfectly functional coalition. […] They work together and they are best friends.”

Reporting on individual countries offers more nuance and represents a clear difference in power and hierarchies. These were mostly written by the Asszonyok authors, and were not translations from elsewhere. The communist women in the MNDSz were still on a quest for forgiveness after World War II. This, together with their admiration for and the expectation of guidance from the USSR, put them in an in-between position vis-à-vis the USSR and the Third World/developing world. Informing the readers of Asszonyok about the lives of women in far-away countries served the goal of socializing the readers into politics both by broadening their geographical horizons and by showcasing the positive change socialism and the Soviet Union carried for women's lives.

One of the most interesting pieces of writing from this period was a report by Zsuzsa Osvát about women in (North) Korea before and after socialism. A writer and journalist in the interwar period, Osvát survived the Holocaust in a “safe house”; that is, in one of the buildings in Budapest under the diplomatic protection of the neutral states. After the war, she started working for Asszonyok, and over time became the editor of the magazine. Her text about Korean women starts with a highly accurate and self-reflective summary of the widespread stereotypes and orientalizing language that characterized the discourse about Korean women earlier. Korean women, in the popular imagery, were frail and subservient, and either mothers of many children or worked “as draft animals on the farmlands”. Moreover, they were illiterate and often used as prostitutes.Footnote 77 Osvát's exaggerated language is a critique of both the Hungarian imaginary of Korean women and Korean society before socialism. Osvát emphasizes the interconnectedness of colonial oppression (Japanese colonial rule) and gender-based oppression, resulting in women's dual subordination in colonized Korea. Moreover, she uses a sympathetic tone when talking about prostituted women, who become “geishas” or “girls of pleasure” as a result of oppression and poverty, a line of argument that characterizes almost all articles in Asszonyok on the subject.

The story about Korean women fits into the interpretation that communism liberates nations (from imperial and colonial rule): these women were aware of their oppression, and realized that “it is only national independence that can bring freedom to the people and only a free people can give human rights to women too”. With the help of the USSR, women in socialist North Korea gained complete equality, illiteracy was eliminated, and thousands of them joined the Korean sister organization of the MNDSz. Osvát argues for the interconnectedness of gender inequality, racism and colonial oppression: “[W]omen's inferiority is just as much a fairy tale told by those in power as is the fairy tale told by the conquerors about the superiority of certain races or peoples.” This is one of the most spelled-out self-critiques of orientalizing language combined with a critique of colonialism; anti-colonialism as anti-racism on the pages of Asszonyok.

The case of Germany was even more perplexing for the socialist women than the much less known world of the Global South. In the aftermath of World War II, solidarity with German women proved to be impossible. Some of the articles voiced the difficulty of recreating bonds with the country, an example being the emotional strength one needed to visit Berlin, the capital of the former enemy (written by Júlia Török, from the left wing of the social democratic party).Footnote 78 There is a strong contrast between treating the WIDF and communist women in general with care, enthusiasm, and intimacy (through the topic of friendship and discussion of private matters), and the way in which any woman suspected of fascist collaboration, and especially German women, were portrayed. Women with a fascist past and upper-class women who refused to give up their class privileges were treated with animosity and were portrayed as selfish, hysterical, and often purely evil.Footnote 79

The generic German woman was embodied by the character of “Grätchen” in an article revealing several important moments of a gendered post-war history of war brides and rape. It was written by Klára Feleki Kovács, a former actress who also wrote trivial romance novels in the interwar period. Some of the language of these returns in her reflective piece on the news that “Six thousand German girls arrived with their fiancés in England”.Footnote 80 As the ban on British soldiers marrying “ex-enemy aliens” relaxed in 1946, fiancées and wives from Germany could emigrate to the UK to reunite with their partners.Footnote 81 Feleki Kovács takes on the role of an omniscient narrator and presents a story told to her by someone “who knows Grätchen and the other Grätchens very well”. However, the emphasis on the plural suggests that the sensational story is more fiction than fact.Footnote 82 Grätchen's character embodies a figure of an inherently evil woman, who uses her femininity and sexuality only to destroy. She even gives away her new-born child for the Nazi cause.Footnote 83 The article emphasizes that it was black US troops with whom she traded sex for chocolate and cigarettes before escaping to the British Occupation Zone. This detail serves to prove Grätchen's hypocrisy, as she had earlier been a devoted believer in racial supremacy, but the text also addresses the existing stereotypes surrounding African-Americans and people of colour. The loose morals of “Grätchen” are in contrast to prostitution seen as necessitated by poverty and lack of proper employment.

In the immediate post-war era, when Hungarian women struggled to bring home their family members held as prisoners of war, the news about happy brides from Germany travelling to the former Allied countries must have raised difficult emotions. Nevertheless, the tone of this article stands out in its misogyny and the blatant hatefulness vis-à-vis the imaginary “Grätchen”, especially in this women's magazine that heralded international solidarity among women. The way the story is told, however, directs contemporary readers’ attention to the silences of trauma and violence. The idea that German women in the Allied zones of occupation were happily fraternizing with military personnel stands in stark contrast to the silence around the mass rapes by the “liberating” armies.Footnote 84 In Hungary alone, tens of thousands of women were raped by members of the Soviet army. The numbers themselves suggest that it was widely known that women were victims of mass rape, even though it was an experience surrounded by silence until the 1990s.Footnote 85

This approach stands in strong contrast to the portrayal of Yugoslav women after the Tito–Stalin split in 1948. Following this split, women's organizations in the Soviet bloc had to break ties with the until then much-admired forerunners of anti-fascist resistance and of women's emancipation.Footnote 86 After months of silence, the MNDSz sent their declaration to the WIDF, in which they pledged not to work with the AFŽ anymore. However, they expressed solidarity with the Yugoslav people and Yugoslav women, who were presented as those misled by Tito and the AFŽ. The letter was published in the news section of Nők Lapja, three months after it replaced Asszonyok:

We know that most Yugoslav women see the true colours of Tito, and they will stand by those who fight for the free and peaceful life of the heroic Yugoslav people against the nefarious clique of Tito and his followers. We believe that we are helping the victory of the true Yugoslav patriots by debunking the current leaders of the Anti-Fascist Front of Women, who are loyal to Tito and his clique, and who spread anti-Soviet propaganda among the Yugoslav women and pursue anti-peace activities.Footnote 87

Disavowing the AFŽ women, many of whom the women from the MNDSz had known personally, allowed the MNDSz and the magazine to stand by their previous writings about the greatness of Yugoslav women in general. However, women who became targets of Stalinist show trials, for example Júlia Rajk in Hungary and Milada Horáková in Czechoslovakia, were accused of Yugoslav links and of spying for Tito's regime.

CONCLUSION

During these formative years of the Cold War world order and of global communism, transfers of ideas and concepts were just as important for the solidification of the MNDSz as for the creation of its journal, Asszonyok. The pre-World War II debates and competition for recognition between the two progressive streams of women's rights movements, feminists and socialists, were decided during this time, feminism (together with social democracy) being pushed to the brinks of forgetting and replaced by socialist women's emancipation politics. For the MNDSz and Asszonyok, internationalism meant solidarity with other women; but the same way as their internationalism was defined by socialism and communism, their solidarity was not unconditional either. Even more importantly than class, political affiliation was decisive. Solidarity with women was reserved for “democratic women”, as socialist women were often described. This early phase of women's internationalism made it unavoidable to think about the relations to women not only with skin colour other than white, but also from countries with a wide range of political past (including the Nazi past of Germany) and present (such as Yugoslavia after the Tito–Stalin split). As Celia Donert emphasized, between the late 1940s and 1960s the idea of “solidarity between women as women across geographical and geopolitical divides” was “more often hemmed around by national loyalties, ideological cleavages, and painful personal decisions”.Footnote 88

Even in this early phase of women's socialist internationalism, allegiances were expected to be first and foremost with the party. These expectations not only led to the disavowal of the formerly admired women in the Yugoslav AFŽ, and hostile language about German women, but also a series of betrayals among the women in the MNDSz and in the Asszonyok magazine's editorial board. Most women participating in founding the MNDSz and the magazine had disappeared from the women's movement by 1949. With the dismissal of all intellectual women from the movement,Footnote 89 the interwar activist memories, knowledge, and experience were also erased, and not only in cases such as Júlia Rajk's. Even Boris Fái and Magda Aranyossi, who never disavowed or openly confronted the communist regime, were sidelined from women's politics and women's rights issues.

Nevertheless, this was a period in which the foundations of the new language of women's emancipation were created. As we have seen, Asszonyok is a valuable source for the ideas and politics of the early MNDSz, a space where ideas were created and discussed. It served as the main forum to communicate and develop ideas about women's socialist internationalism and, through these, also shape the domestic women's rights agenda. Asszonyok's international sections are one of the earliest places where race, gender, class, and ethnicity could be discussed and connected with. Encounters with women and children of different skin colour, religion, and culture enabled the discussion of matters of race and ethnicity when crucial issues such as the situation of Hungary's Roma population were off the official political agenda. Writing about women from all over the world, the state socialist women's rights agenda that was simultaneously emancipatory (with its access to work and education) and traditionalist (with its focus on family and motherhood) was taking shape. The period between 1945 and 1949 shaped the language of women's rights and the discourse on race and ethnicity for the coming decades, even if the women shaping the discourse would not be the same.