Introduction

In recent years, companies worldwide have started taking action to pursue the objectives included in the United Nations Agenda 2030 (Bebbington & Unerman, Reference Bebbington and Unerman2020). Including 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs), the Agenda 2030 is the first attempt to help companies and communities achieve core sustainable objectives such as environmental care and reduction of social issues (KPMG, 2020; United Nations, 2015).

Alongside this, multiple tools and solutions have been adopted to address such challenges, such as the development of sustainability reports and broad stakeholder engagement initiatives (Adams, Reference Adams2017; Pizzi et al., Reference Pizzi, Caputo, Corvino and Venturelli2020a). Notably, companies can implement some sustainability management tools whose objectives are different (measurement and communication) and provide various solutions to sustainability issues: they can be divided into four groups (Hörisch, Ortas, Schaltegger, & Álvarez, Reference Hörisch, Ortas, Schaltegger and Álvarez2015). The first group is sustainability accounting tools (i.e., material flow analysis and material flow cost accounting); the second ones give managers information used to take decisions (i.e., eco-efficiency indicators); the third group is represented by those tools that can be helpful to improve the impact of products and services on the environment (i.e., sustainable design tools and product carbon footprint); finally, the last group is relative to communication and reporting (it suffices to think about sustainability labels). Hörisch et al. (Reference Hörisch, Ortas, Schaltegger and Álvarez2015) highlight how implementing these tools effectively reduces environmental impacts produced by companies. Particularly challenging was the impact of the coronavirus disease pandemic (United Nations, 2022), which had different consequences on the SDGs, especially on gender equality, affordable and clean energy, decent work, and economic growth, even though those countries whose SDG performances were high before the pandemic suffered less than other countries (Elsamadony, Fujii, Ryo, Nerini, Kakinuma, & Kanae, Reference Elsamadony, Fujii, Ryo, Nerini, Kakinuma and Kanae2022; Iazzi, Ligorio, & Iaia, Reference Iazzi, Ligorio and Iaia2022).

Current research has shown how such a phenomenon includes not only large companies but also involves small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Bartolacci, Caputo, & Soverchia, Reference Bartolacci, Caputo and Soverchia2019). Specifically, Johnson and Schaltegger (Reference Johnson and Schaltegger2016) reveal, through a systematic literature review, that sustainable tools have little or null use in SMEs. On the other hand, while confirming the usefulness of these instruments in SMEs, Küchler, Nicolai, and Herzig (Reference Küchler, Nicolai and Herzig2023) highlight that they are more frequently implemented in large companies. In particular, Venturelli, Caputo, Pizzi, and Valenza (Reference Venturelli, Caputo, Pizzi and Valenza2022) reveal how, in the SME context, engaging with the stakeholder is becoming a central aim. It requires modern and more interactive solutions to both promote accountability and open innovation. However, SMEs deal with multiple difficulties when facing sustainability. SDGs are oriented toward pursuing general goals, so SDGs rarely match SMEs’ needs (Smith, Discetti, Bellucci, & Acuti, Reference Smith, Discetti, Bellucci and Acuti2022). Moreover, the increase in technologies and tools for accountability has led to a debate among scholars on which approaches SMEs need to consider for contributing to sustainable development while being accountable (Dalton, Reference Dalton2020). The introduction of modern concepts such as the Agenda 2030 and new digital technologies is a matter of both opportunities and risks. In particular, risks could lie in the anxiety that innovation can stimulate in the business actors and also concerning the integration of sustainable best practices outside the product or service realisation and within the corporate environment (Ewe, Sheau, & Kwai Choi Lee, Reference Ewe, Sheau and Kwai Choi Lee2014).

Among different solutions, adopting ‘gamification’ for sustainability is still a new topic in literature (Silic, Marzi, Caputo, & Bal, Reference Silic, Marzi, Caputo and Bal2020). Including a set of actions and, thus, interactive games, ‘gamification’ is a modern approach to both engaging with external and internal stakeholders while reaching core business objectives (Cardador, Northcraft, & Whicker, Reference Cardador, Northcraft and Whicker2017). In management practice, gamification is a valuable tool for allowing users and employees to learn and improve their professional skills and build more solid relationships within and outside workplaces (CIMA, 2020; CPA, 2016). Specifically, the study proposed by Oppong-Tawiah, Webster, Staples, Cameron, Ortiz de Guinea, and Hung (Reference Oppong-Tawiah, Webster, Staples, Cameron, Ortiz de Guinea and Hung2020) aimed at encouraging pro-environmental behaviours among employees using gamified design principles. Specifically, using gamification, the study showed how it is possible to promote environmentally friendly behaviours by reducing electricity consumption. Another application of gamification in sustainability relates to the field of transportation. The study proposed by Marcucci, Gatta and Le Pira (Reference Marcucci, Gatta and Le Pira2018) discusses the use of gamification in transport policy-making to foster engagement and behaviour change. It presents a new approach to gamification design using stated choice experiments to elicit players’ preferences towards various structural gamification components and identify their optimal combination. Finally, the potential of gamification in sustainable tourism is also worth mentioning. By exploring the role of gamification concerning the three pillars of sustainability (environment, social, and governance), Negruşa, Toader, Sofică, Tutunea, and Rus (Reference Negruşa, Toader, Sofică, Tutunea and Rus2015) demonstrate that gamification can improve the tourist experience, promote responsible behaviour, increase brand loyalty, and have positive impacts on social and environmental sustainability. It can also help to educate and integrate local communities and cultural values. Furthermore, it emerges how gamification tools can create new products, train employees, and educate tourists and residents while minimising negative impacts on the community and the environment.

In this context, the modern start-up ‘AWorld’ established in 2019 and supported by the United Nations is a virtuous example of gamification for companies and communities that want to be part of the Agenda 2030 sustainable paradigm. Moreover, as an SME fully involved in the mission of promoting sustainability in businesses and as an Italian benefit corporation (Law no. 208 of 28 December 2015) and certified B-corp (For reference: https://www.bcorporation.net/), the ‘AWorld’ new approach to sustainability represents an interesting scientific case in the debate. Aiming to understand why ‘gamification’ is an effective tool for SDGs’ contribution in the present case and to explore how ‘AWorld’ is supporting the pursuit of the UN Agenda 2030 among SMEs, the present research makes use of a case study approach to provide an answer to these two main research questions (Yin, Reference Yin2003). Specifically, content analysis is adopted, and an interview is used to triangulate the collected data (Hoque, Parker, Covaleski, & Haynes, Reference Hoque, Parker, Covaleski and Haynes2017; Krippendorff, Reference Krippendorff2018).

The contributions of the study are twofold. First, this study advances research on SDGs’ contributions by demonstrating that SMEs are approaching the new sustainable development challenges through a modern approach. Furthermore, this study provides evidence of the role played by gamification in supporting businesses’ accountability to the Agenda 2030. Finally, contributing to a modern strand of literature, the present study offers new insights into the scientific literature on gamification characteristics and organisational implementation. Few contributions highlight SMEs’ role in adopting SDGs, even though the vital role of these enterprises in the world economy (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Discetti, Bellucci and Acuti2022) requires a deeper involvement in implementing the UN sustainable goals.

The structure of the paper is as follows. First, the scientific background of the main topic is provided. Next, the theoretical framework is described, and the case is presented. Subsequently, methods of analysis are described. Next, findings are provided and discussed. Finally, conclusions and implications for research are included.

Background

SMEs’ contribution to the Agenda 2030

In recent years, the relevance of sustainability issues has seen increasing interest in both public bodies and private companies. Sustainability is linked to sustainable development, which relates to the actions that need to be taken to support development in current times while not reducing the resources for the next generations (Brundtland & Khalid, Reference Brundtland and Khalid1987). As institutional actors can create or change social and economic dynamics and provoke a change in the environment, businesses are core actors in the path towards sustainable change (Elkington, Reference Elkington1994). Specifically, businesses are now trying to identify ideal trade-offs between optimal product, service performance, and improved social and environmental effects to create a sustainable value proposition for businesses. This is connected to the duality of businesses’ contribution to sustainability, such as sustainable innovation and corporate sustainability (Boons & Lüdeke-Freund, Reference Boons and Lüdeke-Freund2013).

In this context, multiple initiatives were taken (Cosma, Principale, & Venturelli, Reference Cosma, Principale and Venturelli2022). For example, in 1992, the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro saw the launch of Agenda 21, a comprehensive plan of action to be taken on a national and local level by the organisations and governments connected to the United Nations System (United Nations, 1992). Similarly, launched in 2000, the United Nations Global Compact is a corporate sustainability initiative to propose a framework for developing more responsible and sustainable businesses (United Nations Global Compact, 2020). Among these initiatives and based on the Millennium Development Goals, the current Agenda 2030 – provided by the United Nations – is a major contribution to pursuing sustainable development through the achievement of 17 SDGs (Sachs, Reference Sachs2012). The 17 SDGs include all the most relevant dimensions of sustainability and provide some specific under-goals to contribute to grand challenges such as environmental care, economic and social development, and biodiversity. Specifically, because of its capability to legitimise business activity, Agenda 2030 has received attention through enhanced transparency and marginal changes in product design (Silva, Reference Silva2021). Moreover, the attention to specific topics – as with biodiversity care – has suggested paying attention to indirect business impacts on the environment and communities (Sobkowiak, Cuckston, & Thomson, Reference Sobkowiak, Cuckston and Thomson2020).

Following the introduction of Agenda 2030, corporations were impacted on different levels. On this point, a bibliometric study published by Pizzi et al. (Reference Pizzi, Caputo, Corvino and Venturelli2020a) contributes to the topic by tracing the boundaries of management research on Agenda 2030. Revealing how Agenda 2030 management research is still quite fragmented, the research has identified four main areas of study: technology, non-financial reporting, education, and developing countries. The technology can influence Agenda 2030 pursuit through the use of recent innovations such as the blockchain since it enhances security, traceability, and transparency for managerial and control issues. In addition, the use of technology is strictly connected to the developing countries’ current path towards the digital economy. However, there is also a need for management research to identify the risks associated with the use of new resources (Gomez-trujillo, Velez-ocampo, & Gonzalez-perez, Reference Gomez-trujillo, Velez-ocampo and Gonzalez-perez2020). On the other hand, scholars have recognised the role of non-financial reporting as pivotal. Concerning the increasing need for transparency and legitimisation, accounting systems must evolve to effectively represent businesses’ contribution to the SDGs (Bebbington & Unerman, Reference Bebbington and Unerman2020). Such a concept is then strictly connected to the role of education in the SDGs. As revealed by Schaltegger (Reference Schaltegger2018), there is still a lack of knowledge of the role played by sustainability within business practices. In these terms, and linking with this study’s premises, gamification appears to be a dynamic and transversal topic, which can simultaneously include the potential advantages connected to digital technologies, the need for accounts on SDGs required by stakeholders, and education on the relevance of sustainability challenges.

In light of the most recent normative changes that impacted sustainability reporting (Pizzi et al., Reference Pizzi, Caputo, Venturelli and Caputo2022a), the relevance of the binomial SDGs and non-financial reporting is an area of interest for scholars. Specifically, different studies tried to explore the topic by focusing on the various entities using SDGs reporting as an accountability tool. Regarding large corporations’ contribution to the Agenda 2030, the study provided by van der Waal and Thijssens (Reference van der Waal and Thijssens2020) reveals how the disclosure of SDGs is still marginal and linked to the adoption of other disclosure practices. Specifically, the authors stated that the field is still evolving and that businesses are hesitant about approaching SDGs. The study provided by Avrampou, Skouloudis, Iliopoulos, and Khan (Reference Avrampou, Skouloudis, Iliopoulos and Khan2019) focuses on a specific sector and offers some insights into banks’ accountability to SDGs. Specifically, the study reveals that, from an organisational side, few steps have been made and that SDGs reporting is not following a specific rationale. From a different side, higher education institutions are also contributing and reporting to the Agenda 2030 by linking their GRI (Global Reporting Initiative)-based disclosures to the SDGs. In this field, social goals are polarised, as goal 4 ‘Quality Education’ (Caputo, Ligorio, & Pizzi, Reference Caputo, Ligorio and Pizzi2021). Similarly, other public institutions have shown a certain interest in disclosing the social goals of Agenda 2030, albeit showing a low grade of accountability (Pizzi et al., Reference Pizzi, Caputo and Venturelli2020b).

Concerning the SMEs’ context, multiple issues arise. First, intended as global goals to pursue sustainable development, the SDGs often cannot meet the need of small businesses that aim to act more ‘locally’ (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Discetti, Bellucci and Acuti2022). Difficulties in the contribution to the SDGs emerge when SMEs face the multiplicity of tools available for SDGs’ accountability. Specifically, SMEs find that using tools, websites, and frameworks for SDG disclosure and contribution is time-consuming and difficult (Dalton, Reference Dalton2020). Finally, while highlighting the need for more government attention, Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Liang, Zhang, Rong, Guan, Mazeikaite and Streimikis2021) suggest that the scarce contribution to SDGs often results in perverse practices such as greenwashing and selective disclosures in the SME context. Interestingly, Pizzi et al. (Reference Pizzi, Del Baldo, Caputo and Venturelli2022b) revealed that the more companies do their business in institutional contexts with a long-term orientation and a balance between indulgence and restraints, the more they are available to disclose their efforts towards the SDGs.

The difficulties that SMEs face in practical contribution to the SDGs are reflected in the perplexities highlighted by scholars. Specifically, it is required to deepen the understanding of different and easier-to-adopt tools that could be both engaging for SMEs’ internal and external actors while effectively contributing to SDGs (Dalton, Reference Dalton2020). Moreover, as companies are prone to the adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies, there is a need for research to understand how SMEs are adopting digital tools for achieving sustainability and contributing to the Agenda 2030 (Belyaeva & Lopatkova, Reference Belyaeva and Lopatkova2020; Pizzi, Venturelli, Variale, & Macario, Reference Pizzi, Venturelli, Variale and Macario2021).

In these terms, the scientific scenario linked to the relationship between SMEs and Agenda 2030 appears fragmented and quite recent. There is need to understand how the ‘local’ feature of SMEs is driving the adoption of sustainable practice appears, as a major challenge for accounting and management scholars. Finally, the scarcity of studies on SMEs and SDGs traces the boundaries of a new field of research on Agenda 2030.

The role of gamification in promoting sustainable development

In recent years, the adoption of gamification practices has been representing a trend in increasing growth because of its positive effects in terms of improved engagement of users and the adoption of good practices as better social interactions as a result of different ‘gameful’ activities (Hamari, Koivisto, & Sarsa, Reference Hamari, Koivisto and Sarsa2014). As described by Deterding, Dixon, Khaled, and Nacke (Reference Deterding, Dixon, Khaled and Nacke2011), ‘gamification’ relates to ‘the use of design elements characteristic for games in non-games contexts’; in other words, ‘gamifying’ is a process that relates to the promotion of certain activities or practices, oriented to certain goals, and characterised by a certain degree of game elements (e.g., rules, time constraints, and challenges). Recently, the increasing interest in such practices has been motivated by the need to engage stakeholders on topics that could relate to financial, social, or environmental dimensions (Robson, Plangger, Kietzmann, McCarthy, & Pitt, Reference Robson, Plangger, Kietzmann, McCarthy and Pitt2015). The validity of adopting gamification results in better user interactions and autonomy, along with increased emotional engagement (Dale, Reference Dale2014; Xi & Hamari, Reference Xi and Hamari2019) as well as to motivate cooperation (Riar, Morschheuser, Zarnekow, & Hamari, Reference Riar, Morschheuser, Zarnekow and Hamari2022).

More recently, the interest in gamification has also been driven by the introduction of digital features in game design. In this field, one relevant approach is detected in advertising gamification. Specifically, by introducing advertising in digital games, boundaries between entertainment and advertising are reduced, resulting in an effective gamification approach (Terlutter & Capella, Reference Terlutter and Capella2013). Furthermore, with the use of more modern technologies on smartphones and mobile devices, it emerges how gamification can also result in the engagement of new generations (Skinner, Sarpong, & White, Reference Skinner, Sarpong and White2018).

Concerning managerial applications of gamification, the tourism sector is one field considered in the literature. Specifically, gamification in this field allows an increased engagement of users, along with the co-creation of experiences and educational paths (Xu, Buhalis, & Weber, Reference Xu, Buhalis and Weber2017). From a different perspective, gamification applications are related to knowledge management practices which, on the other hand, find more difficulty in application in the short term (Friedrich, Becker, Kramer, Wirth & Schneider, Reference Friedrich, Becker, Kramer, Wirth and Schneider2020).

Also, the accounting practice has seen the application of gamification practices. In particular, evidence is available concerning accounting education practices. In recent years, multiple tools have been adopted – mostly in higher education environments – to try and effortlessly improve sustainability management and accounting learning by people (Caetano & Felgueiras, Reference Caetano and Felgueiras2021). Specifically, the study by Silva, Rodrigues and Leal (Reference Silva, Rodrigues and Leal2021) revealed how students can be motivated and engaged in accounting curricula if gamification is adopted. On the other hand, evidence emerges in sustainability control and accountability practices. Specifically, in the SME field, little research has discussed the topic, and it has emerged that it can be a solution for rewarding employees besides the managers when considering sustainability goals (Johnstone, Reference Johnstone2022).

Concerning the relationship between gamification and sustainability, few contributions have been published in management and accounting literature. This approach, recently introduced in strategic planning processes (Mandujano et al., Reference Mandujano, Quist and Hamari2021) as highlighted by Douglas and Brauer (Reference Douglas and Brauer2021), is particularly suitable and favourable for sustainable initiatives. They point out that gamification has already been used to improve pro-sustainability attitudes (with particular regard to sustainability education, energy reduction, transportation, air quality, waste management, and water conservation), showing a more positive effect in comparison to other methods, for example in terms of more prolonged psychological engagement. Moreover, Morganti et al. (Reference Morganti, Pallavicini, Cadel, Candelieri, Archetti and Mantovani2017) demonstrated gamification’s role in generating pro-environmental behaviours, while Berger and Schrader (Reference Berger and Schrader2016) revealed its efficacy in encouraging sustainable nutrition behaviours. By the way, Xu, Du, Shen, and Zhang (Reference Xu, Du, Shen and Zhang2022) discovered that four perceived gamification affordances, which are competition, interactivity, self-expression, and autonomy, support psychological ownership and consumer citizenship behaviour and, in particular, a high level of psychological ownership towards gamification encourages these behaviours.

Exploring the field of energy reduction through gamified applications, the study of Mulcahy, Russell-Bennett, and Iacobucci (Reference Mulcahy, Russell-Bennett and Iacobucci2020) reveals that two core elements of success for gamification in sustainability are enjoyment and knowledge sharing. However, scepticism also emerges from scholars’ thoughts. Approaching the binomial corporate social responsibility and gamification, Maltseva, Fieseler, and Trittin-Ulbrich (Reference Maltseva, Fieseler and Trittin-Ulbrich2019) manifest their doubts by explaining that gamification apps often fail to build solid sustainability attitudes in users and how the adoption of gamification practices can reduce the interest of users in products or services. On a different side, an exciting contribution is made by Souza, Marques, and Veríssimo (Reference Souza, Marques and Veríssimo2020), who explore how gamification can help the achievement of the SDGs in the tourism sector. The authors reveal how this approach can be effective, only if well directed toward the main sustainability challenges and following further investments by institutions.

Similarly, Hsu and Chen (Reference Hsu and Chen2021) clarify that gamification use in sustainability must also consider the user attitude and satisfaction related to the platform use. However, the authors also reveal that current literature needs to focus on the behavioural sphere of users to capture the effectiveness of gamification use. At last, it has to be described that a significant gap in the literature is connected to the lack of exploration of the post-gamification processes: often, literature has focused on gamification applications and activities, but little research has explored how the collected information is used (Guillen Mandujano, Quist, & Hamari, Reference Guillen Mandujano, Quist and Hamari2021).

Aiming to understand which innovative use of gamification can be done by SMEs in contributing to the SDGs and to identify which gamification practices are available for Agenda 2030 accountability and contribution, the present research aims to answer the following two research questions:

RQ1: Why promoting gamification tools is a practical approach to Agenda 2030 contribution by SMEs?

RQ2: How are gamification tools helping improve Agenda 2030 contribution?

Theoretical framework

Studying gamification models and related applications is a new field in management and accounting literature. Few authors have approached the topic, and currently, multiple perspectives are available on the concept (Deterding et al., Reference Deterding, Dixon, Khaled and Nacke2011). Among the published studies, AlSkaif, Lampropoulos, van den Broek, and van Sark (Reference AlSkaif, Lampropoulos, van den Broek and van Sark2018) have developed a model to explore a gamification model for citizen engagement in energy applications. In particular, the authors identify the fundamental components (including technical, behavioural, and economic elements) that must be considered in a gamification process for fulfilling smart meters requirements. Papaioannou et al. (Reference Papaioannou, Dimitriou, Vasilakis, Schoofs, Nikiforakis, Pursche and Garbi2018) developed a different framework that focuses on the technical side of the gamification process while supporting the use of low-cost devices for citizen engagement in the energy wastage field.

Among the various theoretical explorations of the main gamification characteristics, one relevant contribution was developed by Werbach and Hunter (Reference Werbach and Hunter2012). Such a framework is a functional and complete tool able to trace the main requirements for an effective gamification process. Concerning its usefulness, prior contributions have adopted this perspective to explore gamification-related phenomena. For example, the study proposed by Lamprinou and Paraskeva (Reference Lamprinou and Paraskeva2015) adopts such a framework to analyse the development of a gamification approach for education. In particular, the article highlights the importance of designing gamified educational environments that focus on engagement mechanics to maintain student motivation by satisfying autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs. The contribution of Sanchez-Gordón, Colomo-Palacios, and Herranz (Reference Sanchez-Gordón, Colomo-Palacios and Herranz2016) adopts this theoretical perspective to understand the results of an empirical test on gamification applications. However, connecting to the present research aims, the study leaves an open question related to the value creation dynamics associated with gamification in workplace environments.

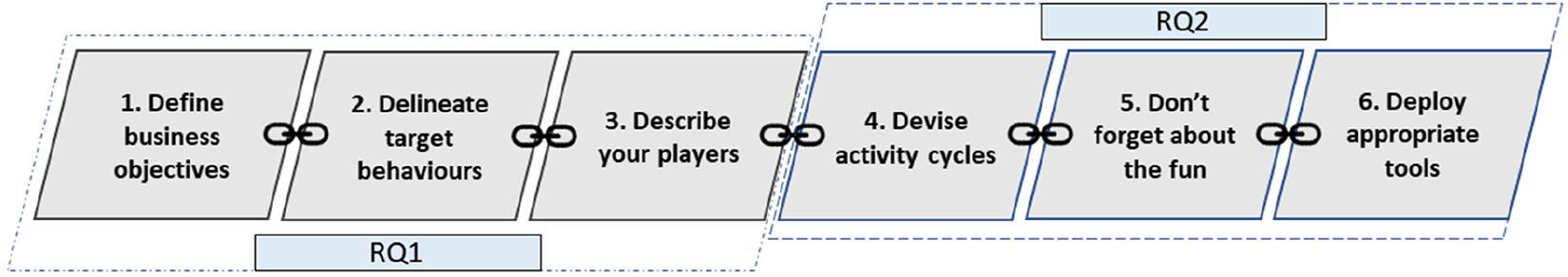

The framework (Fig. 1) proposed by the two authors is structured into six main steps.

Figure 1. The gamification framework.

Define business objectives

The first step relates to defining the goal to be pursued by the gamification process or application. Specifically, concerning the main aim of pursuing the sustainability goals related to Agenda 2030, the broadness of SDGs involvement is a measure of contribution effectiveness (Pizzi et al., Reference Pizzi, Rosati and Venturelli2020c).

Delineate target behaviours

After deciding which goals to pursue, Werbach and Hunter (Reference Werbach and Hunter2012) suggest that a significant challenge is linked to the definition of a set of target actions to be done by users. Specifically, the actions must be aligned with the previously set goals and achievable.

Describe your players

The third goal of the gamification framework links with the players involved. The authors of the framework suggest that such a process requires the acquaintance of the subjects by collecting information on them before the development of a gamified environment.

Devise activity cycles

Focusing attention on the dynamics of gamification, players must be involved in cycles that include motivation for their actions, actions, and feedback. The development of a gamification design needs to provide motivation (e.g., rewards and visibility in the company) which has to link with coherently developed actions. Finally, feedback can close the cycle and motivate the player to participate in new participation.

Do not forget about the fun

One key aspect of gamification is fun. Following Lazzaro (Reference Lazzaro2004), four main types of fun emerge: easy, hard, people, and serious fun. ‘Easy fun’ inspires exploration and role play, while ‘hard fun’ focuses more on goals, constraints, and strategy. People’s fun is a vehicle for creating mechanisms of interaction and teamwork, while ‘serious fun’ changes players’ way of thinking, and it is an effective driver of change in the real world. For the study’s aim, all four fun types are explored.

Deploy appropriate tools

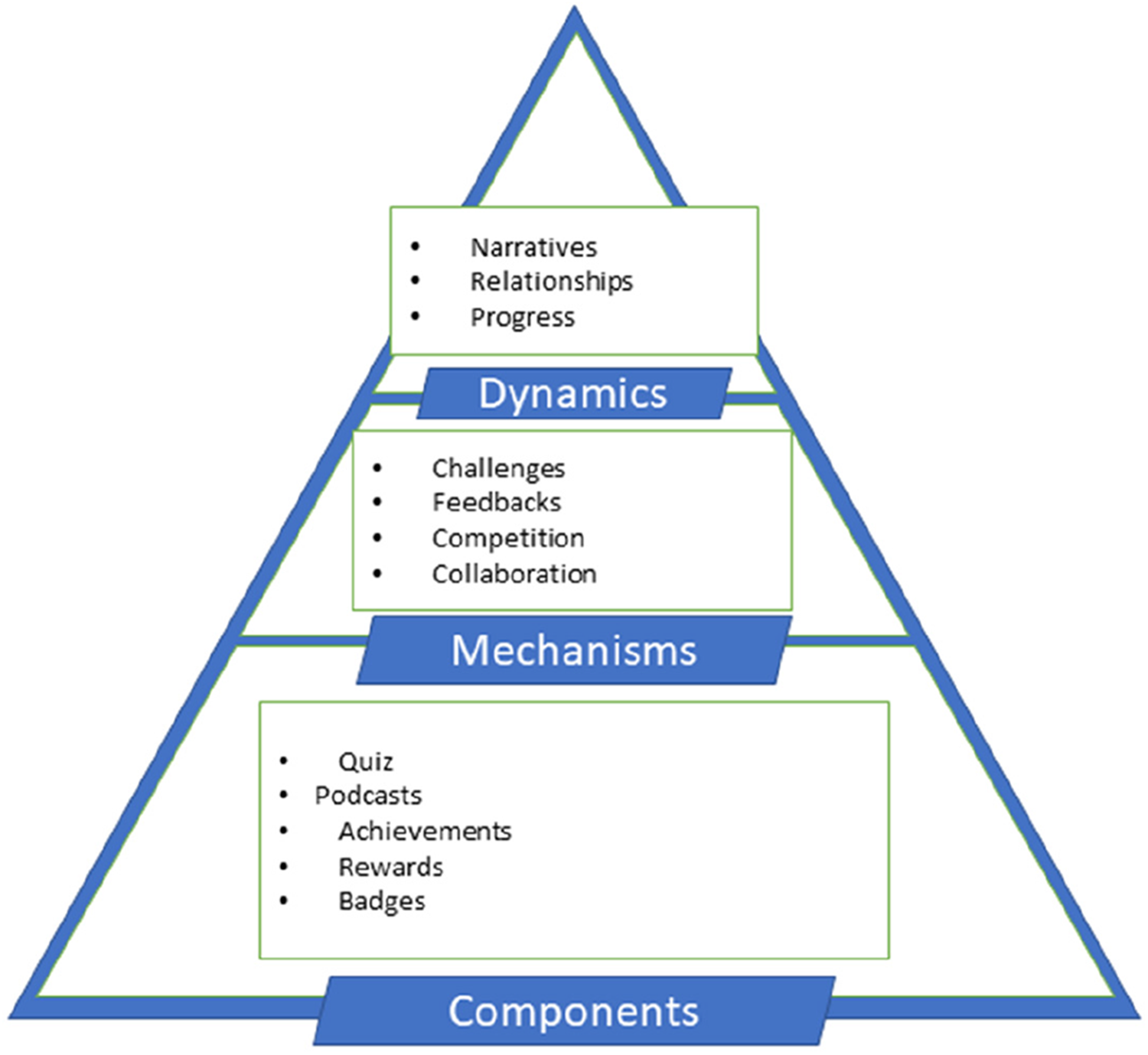

The last step relates to the understanding of the processes. Specifically, to identify which tools have been considered, the pyramid proposed by Werbach and Hunter (Reference Werbach and Hunter2012) that distinguishes components (specific actions), mechanisms (basic processes), and dynamics (big picture elements) are adopted.

In these terms, following the approach proposed by Huber and Röpke (Reference Huber and Röpke2015), the six components of the gamification framework have been used as a reading lens to read ‘AWorld’ gamification solutions and approaches. Coherently to Werbach and Hunter (Reference Werbach and Hunter2012), the six areas of the framework have been linked to the two main research questions.

Case presentation

‘AWorld’ is an application and platform that engages, informs, and measures the impact of people to promote sustainable lifestyles. It is a comprehensive solution for companies that want to engage their stakeholders: gamification, edutainment, community, impact tracking, rewards, corporate social responsibility, and ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) reporting (Fig. 2).

What makes ‘AWorld’ particularly relevant for SDGs contribution links with being the official app selected by the United Nations to support the ActNow campaign for the individual contribution to Agenda 2030.

As told by the company CEO in our interview (see subsection ‘Data triangulation’ in the section ‘Findings’), ‘AWorld’ is a recent project developed between the end of 2018 and the very beginning of 2019. Specifically, the project was born from a previously established service of e-commerce in the fashion industry. However, the need to introduce sustainable development contributions in the platform has moved the attention of the founders to creating stakeholder engagement applications for sustainability awareness. After creating the first alpha version of the app, a partnership with the United Nations was born.

Nowadays, ‘AWorld’ is a dynamic benefit corporation that is contributing to the agenda of 2030 by helping businesses keep track of their footprint, along with educating their employees on sustainability core topics. Specifically, as the company discloses on its official website (https://aworld.org/), its strategy considers three core steps. First, ‘AWorld’ provides some features able to measure and classify people’s impact on key areas of sustainability. Next, the company offers a series of storytelling content necessary for sensitising users to sustainable development. At last, after learning users’ routines – in terms of impacts on sustainability – the platform ‘teaches’ users how to sustainably improve their routines.

The decision to consider ‘AWorld’ as a case study for the present research has been motivated by multiple elements. First, considering the requirements included in the EU recommendation 2003/361, this company can be identified in the category of micro, small, and medium enterprises because of number of employees being lower than 250 and total assets not exceeding the threshold of 50 million (information collected from BvD’s Aida database).

As a benefit corporation associated with the United Nations, ‘AWorld’ is a virtuous case of contribution to the Agenda 2030 and its 17 SDGs. In particular, the business story of ‘AWorld’ as the product of a partnership between a private small business and the United Nations for developing an innovative mobile app makes it a unique case within the environment of mobile apps for sustainable development contribution.

Considering the aims of the present case study, the core business of the company – related to the adoption, development, and sharing of gamification tools for sustainability – makes it a unique opportunity for exploration.

Finally, as a business born in 2019 and characterised by a short history in online retailing services, ‘AWorld’ exploration allows us to explore the dynamics of SMEs’ contribution to Agenda 2030 and the evolutionary paths involving modern digital services corporations.

Methods

The need for a better understanding of the practices adopted by SMEs in contributing to and supporting contribution to Agenda 2030 finds a suitable methodology in the qualitative case study. Precisely, following Yin’s (Reference Yin2003) suggestion, a case study approach is preferred when chosen research questions are ‘how’ and ‘why’ types. Concerning case studies, such an approach has been recognised as suitable for this research because of the novelty and scarcity of information related to the application of gamification for sustainable development (Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt1989). Considering the theoretical approach of Werbach and Hunter (Reference Werbach and Hunter2012), the case study approach allows us to link theory with practice by aligning theorisation with modern world complexities (Ragin, Reference Ragin1997; Welch, Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, Piekkari, & Plakoyiannaki, Reference Welch, Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, Piekkari and Plakoyiannaki2022). In particular, an interpretive approach has been adopted by focusing on the identification of themes, patterns, and narratives that emerge from the data (Piekkari, Welch, & Paavilainen, Reference Piekkari, Welch and Paavilainen2009). Also, as a core part of the analysis, the role of technology is addressed through the case study to identify the underlying mechanisms (Bygstad, Munkvold, & Volkoff, Reference Bygstad, Munkvold and Volkoff2016; Ragin & Becker, Reference Ragin and Becker1992).

Moreover, the need to explore the features of a modern platform has driven the adoption of a single case study analysis to provide more evidence on the SMEs’ contributions to SDGs and advance theory on gamification (Johnstone, Reference Johnstone2022; Masiero, Arkhipova, Massaro, & Bagnoli, Reference Masiero, Arkhipova, Massaro and Bagnoli2020). Subsequently, a case study analysis protocol has been developed (Yin, Reference Yin2009). Specifically, three core steps were included in the analysis: (1) data collection, (2) data analysis, and (3) data triangulation.

Data collection

First, the development of the study has required gathering information to be analysed. Concerning a digital services company that offers gamification tools, the data collection has followed two paths.

To include the information available on the official website, data have been extracted using the qualitative analysis software ‘NVivo’ and its webpages capture tool ‘NCapture’ (Hai-Jew, Reference Hai-Jew2014). Moreover, to deeply explore the application’s functioning and its parts, credentials for a demo version of the platform were provided to the authors. Thus, being a mobile app available for smartphones, two researchers downloaded and extracted the information included in the ‘participants’ section of the application. Such data included the sustainability performances of the users’ group and not user-specific information.

Data analysis

The analysis of the collected data was carried out using content analysis. As stated by Krippendorff (Reference Krippendorff2018) and Unerman (Reference Unerman2000), content analysis is a process that allows the codification of context (e.g., texts, documents, and images) into categories to derive quantitative representations of a phenomenon. In this research, the content analysis has been divided into three steps: (a) unit identification, (b) codification, and (c) analysis of the results. First, as in Jose and Lee (Reference Jose and Lee2007) and Galetsi, Katsaliaki, and Kumar (Reference Galetsi, Katsaliaki and Kumar2022), units were identified on the website published contents and the mobile application contents. As in Huber and Röpke (Reference Huber and Röpke2015), the gamification framework has been considered and data coded using the software ‘NVivo’ to codify the data. In this phase, and to increase codification reliability, two researchers codified and cross-checked codification nodes’ validity (Lombard, Snyder-duch, & Bracken, Reference Lombard, Snyder-duch and Bracken2002). Finally, the collected contents have been analysed in light of the two main research questions.

Data triangulation

A process of data triangulation has been operated to increase the main data analysis validity and to collect further evidence on the two research questions. Specifically, as stated by Hopper and Hoque (Reference Hopper and Hoque2006), data triangulation involves the use of different sources of data in a single case study (e.g., interviews, questionnaires, and documents). It allows researchers to cross-check data and gather information that is not available if analysed through the main source of information. Following this concept, the authors gathered information collected from the official web pages and an interview with the president and co-founder of the company. In particular, the interview occurred online on the 3rd of August 2022 and was performed as an unstructured interview. Being an approach that allows a deep and profitable interaction with a subject of interest, the unstructured interview approach was adopted to collect information on the company’s story, narrative, practices, and mission (Qu & Dumay, Reference Qu and Dumay2011). Next, the triangulation framework adopted for the main data analysis was used to analyse accessory data. At last, findings have been compared for triangulation (Ligorio, Caputo, & Venturelli, Reference Ligorio, Caputo and Venturelli2022).

Findings

Define business objectives

To understand the business objectives of the company and the promoted gamification platform, contents of the 17 SDGs have been considered (United Nations, 2015).

First, the commitment to the Agenda 2030 is a key feature of ‘AWorld’. Specifically, looking at the official website homepage, the company clearly states that the main links with the need to create awareness and share knowledge on SDGs and the impact that they can have on everyday life:

AWorld and the United Nations joined forces to create awareness around the Sustainable Development Goals and engage citizens in living sustainably. ActNow is the UN campaign for individual action on climate change and sustainability. Source: https://aworld.org/act-now/

In addition, the contribution to Agenda 2030 is realised through the pursuit of two main missions. First, ‘AWorld’ aims to promote impact engagement. This approach sees the first phase of user profiling in which it is possible to identify user habits and the related impact on sustainability. Next, the educational section of the promoted platform is addressed to educating and entertaining users in sustainability learning through the use of the SDG contents:

We ensure all of our facts and sources are verified and that we bring in diverse voices to tell these stories the way they should be told.

We utilize our Sustainable Development Goal insight to weave together content that educates and inspires while ensuring retention and memorability. Source: https://aworld.org/impact-engagement/

Finally, the approach ‘engage and reduce’ aims at translating SDGs in users’ everyday life, coherently with their habits.

The second pursued objective relates to the project ‘NetZero’. After the Paris 2015 agreement, ‘AWorld’ focuses on the three areas of the GHGs (GreenHouse Gases) protocol, thus providing a deeper focus on the environmental section of SDGs contribution.

Delineate target behaviours

Connected to the defined two major goals, ‘AWorld’ promotes a series of actions for being accountable while contributing to Agenda 2030 goals through gamification.

“In particular, as the company states, the main goal related to the adoption of the promoted platform is connected to the change of everyday habits of users. To do so, the application that comes with the subscription aims to measure and change people’s behaviour daily:

Sustainability is a personal, continuous, and always evolving journey. AWorld meets you where you are and helps you every step of the way by offering real insights, inspiring challenges, and teaching you something new everyday.

We’re there with you everyday, helping make it easier for each decision to be a little more sustainable.”

Source: https://aworld.org/features/

Moreover, the second relevant behaviour that is being promoted links with accountability practices. Specifically, ‘AWorld’ wants to produce data for measuring the businesses’ contribution to sustainability via SDGs. In addition, the application itself provides teams with the possibility to check how users are behaving and how sustainable they are performing:

Make internal and external ESG and SDG reporting simple and easy with AWorld’s unique data exporting features.

See the progress and impact your team has made, easily pull engagement metrics and see which SDGs your team has covered with just one click.

Scope 3 measurement options available.

Source: https://aworld.org/features/

Such evidence is particularly relevant since it is possible to identify how this gamification solution carries the mission of promoting users’ more sustainable habits and accountability for companies that aim to contribute to sustainable development. Moreover, as the official website states, ESG metrics and SDG reporting make collected data more usable for externals.

Describe players

The third step of the gamification strategy links to the understanding of the participants and the identification of the features that characterise them. As disclosed on the main website, one key objective of ‘AWorld’ is to engage with all the stakeholders by accompanying them in the achievement of sustainable lifestyles:

A World allows you to engage all your stakeholders and make them a part of the transition, aligning them to your ESG and NetZero strategy and unlocking the power of your organization to fight climate change.

Source: https://aworld.org/for-whom/

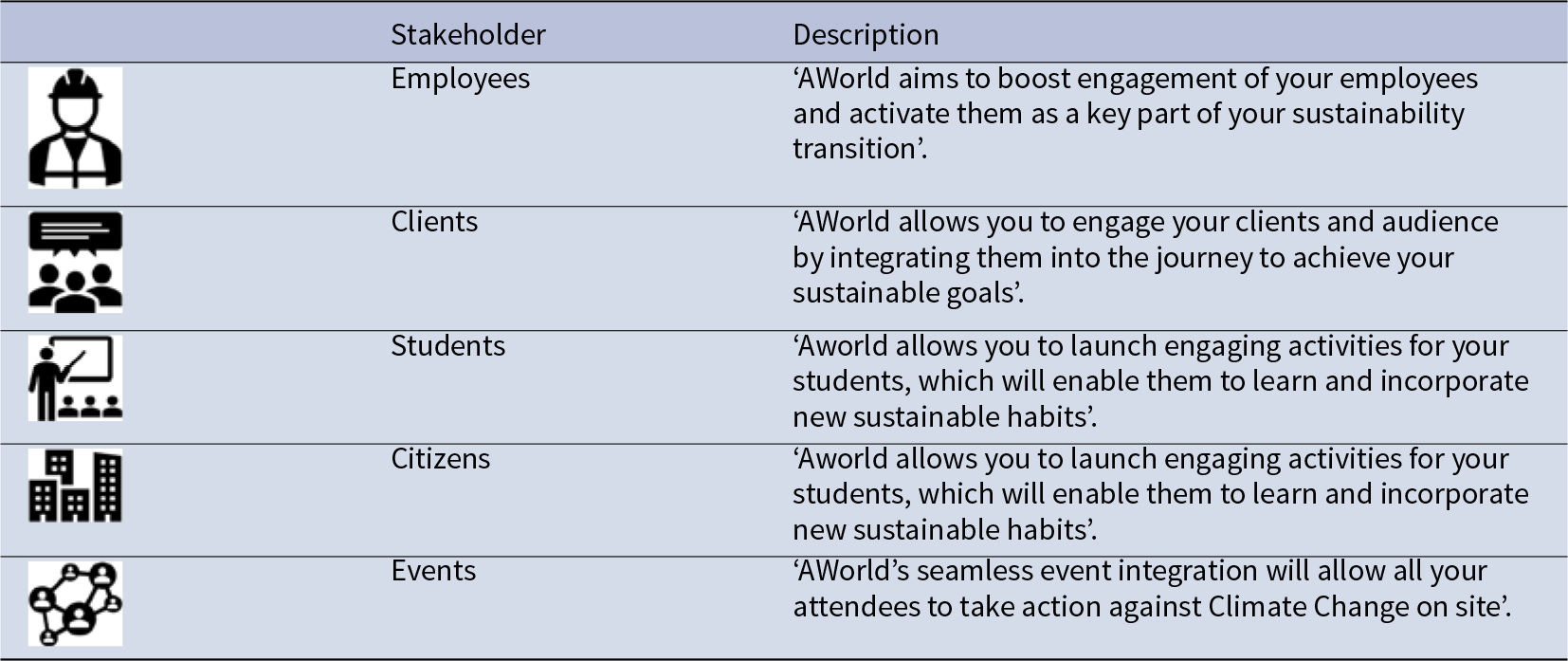

However, to promote a more focused and effective strategy, ‘AWorld’ also deepens its attention on core stakeholder categories (Table 1)

Remarkably, a general category of subjects is also included besides the most relevant stakeholders. In particular, as the company states, the versatility of the gamification solution is suitable for engaging users during events while promoting accountability.

Moreover, the analysis of the engaged stakeholders reveals the institutional centrality of ‘AWorld’. Specifically, following Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury’s (Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2013) conception of institutional logic, it emerges how the company is involving multiple actors and related logic for sustainable development, thus, revealing a broad and effective strategy.

At last, the analysis of the ‘participants’ section – which contains non-specific data of testing users and is available from the demo group whose access was made available to the authors – has revealed how eliminating boundaries and participants classification through the use of a single ranking allows users to collect easy-to-access information on team sustainability performances. Specifically, the mobile app allows to see how participants scored concerning the most relevant sustainability fields and track their effort by considering their impacts in terms of reduced emissions and/or water use.

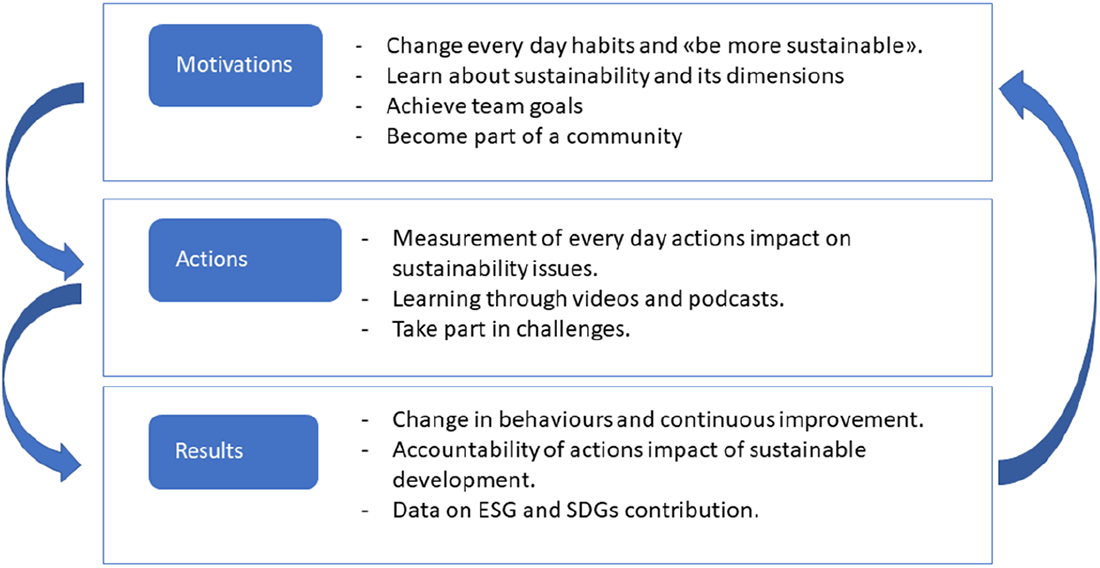

Devise activity cycles

The second part of the analysis relates to understanding the actions and contents being proposed to users. In particular, this section aims to describe how the combination of motivations, actions, and results are impacting users’ experience and desire to use the ‘AWorld’ gamification platform (Huber & Röpke, Reference Huber and Röpke2015).

Concerning the activity cycle, it is possible to identify from the company web disclosure that the three core steps are recognisable in the promoted main steps of the use of the platform (Fig. 3).

It is relevant to engage users in adopting this platform. First, ‘AWorld’ considers the relevance of the current sustainability issues and the increasing awareness of such aspects within people’s life. Specifically, it aims to make users think about their daily habits and create awareness of sustainability impact. This matches with the second motivation, which is related to the education of the users, who are stimulated to increase their knowledge of SDGs and United Nations missions. The community feature and the possibility of pursuing Agenda 2030 with work teams is a social motivation for users.

Do not forget the fun

Being a small business that promotes gamification to achieve Agenda 2030 pursuit, one key element of the platform must concern the deployment of fun activities for users. Using the concept of fun, as described by Lazzaro (Reference Lazzaro2004), a mixture of the four types emerges from the analysis.

First, ‘hard fun’ – identified as the type of fun connected with the creation of emotions such as personal challenge and frustration – is embedded in the gamification feature itself. Specifically, the application of ‘AWorld’ constantly challenges users with personalised challenges and objectives to be pursued in certain periods (Fig. 4).

The second type of fun, recognised as ‘easy fun’, links with a generalised sense of ambiguity, incompleteness, and detail that makes users want to know more about the path they are following. To assure ‘easy fun’, ‘AWorld’ offers a combination of storytelling – to make users increasingly aware of the sustainability world – quizzes, and personal challenges that offer users badges and further progress in their personalised path to better and sustainable habits.

Next, people’s fun appears as a core feature of the entire gamification experience. Specifically, offering the possibility to measure users’ impact compared to their work team provides the occasion to build or enforce workplace relationships. This is possible through the sharing of internal challenges and scores. ‘AWorld’ provides the possibility to join community challenges to promote major goals such as planting trees or establishing bee hives.

Finally, ‘serious fun’ is the most addressed path of fun. Specifically, ‘AWorld’s’ main goal includes not only making the sustainability first approach more enjoyable for people that are new in the field but also aims to change people’s behaviour in everyday life. Such a process is made possible by a set of personalised contents and challenges, along with quizzes, that keep the user engaged in the entire process.

Deploy appropriate tools

The definition of a gamification process is composed of multiple components, mechanisms, and macro-level dynamics. As represented in Fig. 5, ‘AWorld’ considers a set of components to be mixed for the achievement of the main goal. Specifically, it was possible to identify a combination of quizzes, podcasts, achievements, and rewards for the engaged user as the main components of the gamification process. Such components are mixed through challenges that involve single-user participation and team sharing through the community development features. Finally, the collection of the insights, along with the shared scores, create the main picture of the app that both increases awareness of Agenda 2030 while promoting fun.

Figure 5. Modified pyramid of Huber and Röpke (Reference Huber and Röpke2015).

Data triangulation

To triangulate the data, the ‘AWorld’ organisation gave the authors the possibility to virtually meet the President and CEO to collect more insights on why this company was driven to contribute to Agenda 2030 and how.

As emerged from the encounter, the relevance of sustainability challenges is embedded in the original idea of development. In the words of the President:

We first started as an online market platform in the fashion industry. However, getting in touch with sustainability issues made us think that we had to promote ‘something positive’: in these terms, we tried to include a system of rewards and engagement to promote sustainability among customers.

This interaction already reveals that small businesses are being impacted by the awareness of sustainability since the very beginning of their activity. However, difficulties emerge when trying to involve new dynamics in users engagement:

First, it was very difficult to share our interest in sustainability through our marketplace because many customers were not or just a little educated on what modern sustainability challenges are or mean. It was then that we understood how a different platform could be necessary.

Thus, it emerges that, even in the modern technological field, SMEs struggle to have attention from customers on sustainability and, thus, be accountable for it. In this situation – as the interviewee reveals – an idea for a new solution came to their minds with the development of a first alpha edition of ‘AWorld’:

We wanted to create a tool for awareness and self-improvement, along with providing companies with an effective system to make them accountable for sustainability. In this case, approaching – and becoming partners – of the United Nations, gave us the possibility to start a completely new different path, and using the Agenda 2030 SDGs as the framework.

Moreover, approaching sustainability differently and as a vehicle between companies and the Agenda 2030 has given the possibility to create a tool of accountability:

Besides the measurement of users’ behaviours and performances on ESG dimensions, our idea is to provide companies with a solution that allows them to improve their disclosures on sustainability, along with the development of their materiality matrices: by exploring the employees’ habits and preferences, it is possible to improve this process.

Concerning the usability of the platform itself, the interview confirms the authors’ idea of strong attention to users’ psychological patterns during the development of the gamification process:

Along with the SDGs framework, experts from multiple fields were engaged in the development of the platform. Specifically, we involved behavioural experts to make a suitable app for employees. Further developments of ‘AWorld’ see a new version that allows users to measure and improve their habits even if not part of a work team or company.

Finally, to confirm our idea on the effectiveness of such an approach for accountability in the SMEs field, the President has revealed that strong attention from the market and institutions is coming:

The service is still very personalised for businesses, but we are getting in touch with many subjects, and we aim to create something more usable for privates. Also, we got a lot of attention from companies belonging to utility sectors, and we are raising the attention of many institutional investors and funds.

Discussion

Analysing the work made by ‘AWorld’ in promoting sustainability while being accountable for it through a new approach has revealed a new path in the world of SMEs’ approach to sustainability and Agenda 2030.

Specifically, adopting an Agenda 2030-focused approach reveals that it is possible to contribute to multiple goals using a single tool, including the adoption of technology and gamification. By the way, an approach based on gamification and new technologies has been encouraging sustainable behaviours (Cardoso, Ribeiro, Prandi, & Nunes, Reference Cardoso, Ribeiro, Prandi and Nunes2019; Whittaker, Mulcahy, & Russell-Bennett, Reference Whittaker, Mulcahy and Russell-Bennett2021), insomuch that Souza, Marques, and Veríssimo (Reference Souza, Marques and Veríssimo2020) use the term ‘eco gamification’, describing the benefits of this approach as well. First, the insights collected reveal that the struggles to be faced by SMEs are still relevant and that perplexity revolves around the different approaches to accountability (Dalton, Reference Dalton2020). Approaching sustainability through the gamification lens has offered ‘AWorld’ the possibility to effectively measure their impact on Agenda 2030 while acquiring insights into the involved users. In particular, ‘AWorld’ has shown how it is possible to be accountable for Agenda 2030 and promote sustainability culture locally and nationally (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Discetti, Bellucci and Acuti2022). This case suggests that the Agenda 2030 framework associated with a proper life-changing system (as with gamification) can avoid negative behaviours such as greenwashing, a common issue within SMEs approaching sustainability (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liang, Zhang, Rong, Guan, Mazeikaite and Streimikis2021). Finally, the ‘all-in-one’ structure of the platform makes ‘AWorld’ an example to follow for SMEs and solves the issue connected to the wide availability of accountability channels (Dalton, Reference Dalton2020).

The adoption of Werbach and Hunter’s (Reference Werbach and Hunter2012) framework of gamification has provided further answers. Specifically, the complexities related to the wide variety of stakeholders interested in SME activity (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Discetti, Bellucci and Acuti2022) find both a solution and a path for engagement in the development of gamification platforms. Concerning the intrinsic characteristics of ‘AWorld’ processes, gamification also provides further positive externalities. Specifically, more knowledge of users’ behaviours is provided using continuous monitoring and measurement of their habits. This is evident when considering the necessity to better explore consumers’ habits in terms of sustainable attitudes (Halder, Hansen, Kangas, & Laukkanen, Reference Halder, Hansen, Kangas and Laukkanen2020; Han, Reference Han2021), also in a perspective of consumer profiling (Larson & Farac, Reference Larson and Farac2019) and marketing segmentation of green consumers (Chan, Reference Chan1999). Thus, the difficulties that emerged in understanding SME customers’ desires and the need for further exploring people’s behaviour around the topics of sustainability are overcome (Hsu & Chen, Reference Hsu and Chen2021; Maltseva, Fieseler, and Trittin-Ulbrich, Reference Maltseva, Fieseler and Trittin-Ulbrich2019).

The present case also carries additional insights concerning the methods that are being used for engaging with users. Specifically, confirming Lodhia, Kaur, and Stone’s (Reference Lodhia, Kaur and Stone2020) conclusions, engaging with stakeholders is not reduced to a single channel of information sharing. Specifically, the use of challenges, quizzes, and community interactions reveals that it is possible to better involve internal stakeholders when traditional tools of accountability do not appear as effective as they should be. Some studies show how interactions could be positive on consumer loyalty (Kunkel, Lock, & Doyle, Reference Kunkel, Lock and Doyle2021) and to reach consumers more easily (Parsons, Reference Parsons2013), a possibility provided by the apps, as interestingly shown also by Brauer, Hildebrandt, and Remane (Reference Brauer, Hildebrandt and Remane2016) with regard to environmental sustainability. However, the relevance of the conscious awareness driven by this app is particularly notable considering its role in consumer behaviour mechanism (Chartrand, Reference Chartrand2005).

Furthermore, the future developments of ‘AWorld’ confirm the path in non-financial accounting and gamification that prior studies have introduced (Mandujano et al., Reference Mandujano, Quist and Hamari2021). Specifically, a new personalised and interactive accountability can be a new solution for overcoming the accountability issues that the current state of the art has detected, such as the difficulties in collecting information from internal stakeholders (e.g., employees) in building the materiality matrix. This study is consistent with the literature focused on green behaviour fostered by new technologies, particularly apps (Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Marsh, Halvarsson, Holdsworth, Waterlander, Poelman and Maddison2016; Suruliraj, Olagunju, Nkwo, & Orji, Reference Suruliraj, Olagunju, Nkwo and Orji2020).

Conclusions

Concluding remarks

This study has offered the possibility of getting in touch with a singularity within the SME field. Specifically, exploring accounting and management literature on SMEs accountability on sustainability issues, it emerges how the topic is still under-explored and requires further explanation of relevant research gaps as the understanding of the little transparency on sustainability by many businesses and the lack of proper tools for accountability. The analysis of ‘AWorld’ as a single case study has provided the possibility to put the lens on an innovative business that, from one side, is opening the path towards Agenda 2030 contribution through gamification and, from the other, is offering the first framework for gamifying accountability in businesses. Thus, by adopting the Werbach and Hunter (Reference Werbach and Hunter2012) framework, it was possible to explore why gamification is an effective approach for promoting Agenda 2030 by an SME and how this can be made possible. The study revealed that, after major pressures from the current social and economic context, sustainability is becoming necessary for all the actors. Such awareness is connected to the need to engage with a large set of subjects with their characteristics and features. In this sense, gamification emerges as the most relevant solution for creating personalised experiences and, thus, dynamic and more effective contributions. Combining the key elements of a gamification framework, ‘AWorld’ could also create a valid channel of information gathering and disclosure that could be useful for internal accountability and external businesses’ non-financial accounts. In these terms, it appears that new smart and mobile technologies such as apps can represent a solution for multiple challenges. In other words, the struggle connected with the implementation of new technologies and new concepts in corporate internal processes can be sustained through the use of more user-friendly tools such as gamification platforms on mobile devices. This appears particularly appealing for traditional sector SMEs, still facing the advent of sustainability challenges.

Theoretical implications

The present study has multiple implications. First, from a theoretical perspective, it emerges as a relevant contribution to the current literature on gamification, focusing mainly on its role within the field of sustainable development. Specifically, considering the literature on gamification and workplaces, this study opens the path to a new strand of research concerning the use of mobile technologies (such as smartphone mobile apps) for promoting sustainability while educating and promoting accountability (Marcucci, Gatta & Le Pira, Reference Marcucci, Gatta and Le Pira2018; Pizzi et al., Reference Pizzi, Caputo, Corvino and Venturelli2020a). The adoption of the theoretical framework proposed by Werbach and Hunter (Reference Werbach and Hunter2012) has revealed its suitability for further research on comparable phenomena. Subsequently, this results in a new point of view on SMEs’ contribution and accountability to Agenda 2030. Specifically, this study has revealed how a single SME can approach sustainability disclosure by helping other organisations achieve enhanced transparency and by being accountable through gamification-related statistics and data. However, the adoption of gamification in SMEs studies is still a new and under-explored field that must receive further attention in the next future. At last, following the findings of Pizzi et al. (Reference Pizzi, Caputo, Corvino and Venturelli2020a) and concerning SDG accounting research, it emerges how gamification can include the main topics related to current and past literature. In particular, the examined case has revealed an attention to the potentiality of technology, the possibility of achieving SDGs contribution accounts, and the education of employees.

Managerial implications

Managerial implications emerge concerning the new development of gamification-focused businesses. Specifically, the case reveals that it is possible to approach sustainability not just as a legitimation tool for the main activity but also as the core businesses itself, by providing a tool for contribution and monitoring. In particular, this study offers insights for technology-focused SMEs by providing a perspective on SDGs’ contribution. Specifically, it emerges how gamification solutions can be embedded within mobile applications for promoting sustainable behaviours both in and outside organisations. Moreover, the complexities that characterise SMEs gathering data for non-financial disclosures can be effectively avoided by integrating accounting practices in gamification environments.

Limitations and future directions

This study is not free of limitations. The adoption of a case study approach offers an interesting insight into the topic of SMEs and accountability but lacks generalizability. Expressly, the consideration of a single business case and the non-availability of a control case or group of entities has provided an early representation of the phenomenon, which requires further empirical tests for the generalizability of the findings. The interpretive case study approach could influence the replicability of the study. In these terms, further studies could enhance the quality of the present analysis by approaching the topic with a different case study approach, as in the case of action research. In addition, further studies could try to gather additional evidence by involving multiple case studies or by comparing different businesses. Finally, the adoption of a single interview for triangulation could be seen as a second limit. Next studies could involve field research to test Agenda 2030 gamification effectiveness among users. Moreover, the understanding of the ‘AWorld’ case can be the object of further exploration. Specifically, a more in-depth analysis of the sustainability performance measurements and disclosure – as a result of the data collection from users – could represent a different perspective for examining the case. Also, it could be useful to study how ‘AWorld’ published information aligns with the main sustainability disclosure standards. Finally, quantitative analysis to test the quality of gamification-based accounts could be useful for deepening knowledge in the study.

Acknowledgements

We thank Rossella Meo – Program Manager at AWorld – and Marco Armellino – Chairman and Co-founder of AWorld – for their kind support in the provision of materials and information for the development of the present study.

Conflicts of interests

The author(s) declare none.

Andrea Venturelli is an Associate Professor at the University of Salento. He is the President of Gruppo Bilanci e Sostenibilità (GBS) and member of EFRAG EWG. He published in many international journals such as Accounting Forum, Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, Meditari Accountancy Research, and Business Strategy and the Environment. He is the Associate Editor of the journal Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility.

Lorenzo Ligorio is a PhD Candidate and Research Fellow in Economics and Management. His research interests and publications are in public administration, corporate social responsibility, and hybrid organisations. He published in many international journals such as Business Strategy and the Environment, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, and Management Decision.

Pierfelice Rosato is an Associate Professor at the University of Bari. His research interests are in business management and organisation. He published in many international journals such as British Food Journal, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, Ecological Indicators, and International Journal of Technology Marketing.

Raffaele Campo is a Researcher at the University of Bari. His research interests are in food marketing, sensory marketing, and sustainability. He published in many international journals such as British Food Journal, Business Horizons, Journal of Food Products Marketing, International Journal of Markets and Business Systems, and Journal of the Knowledge Economy.