The boundaries of Business History, as a discipline, are constantly revisited.Footnote 1 There have been contradictory views on the nature of our field for many decades, and they continue to exist today, reformulated by new generations and interest groups. As if these differences were not enough, there are also substantial disparities on when and how the subject has evolved worldwide.Footnote 2 Furthermore, business historians have explored new theoretical and methodological avenues in the past two decades. Highlighting the current growing richness and intellectual diversity of the field does not preclude recognition that business history, for much of its existence, has overwhelmingly relied on evidence from and been focused on issues related to the historical experiences of North America, Western Europe, and Japan. This mostly Western-centered approach that has characterized mainstream approaches to business history also has assumed masculine norms.Footnote 3

I am not denying the fact that the discipline has expanded to new geographies in the past decades. I simply suggest, as a departure point, that the business history of the rest of the world was largely neglected for many decades, and, when it did make the headlines, it was primarily in dedicated or special issues. Recent analyses of publication patterns for Chinese, Indian, or Latin American business history articles in mainstream business history journals support this claim.Footnote 4 An ongoing research project led by Beatríz Rodriguez and Julio Zuluaga has revealed that 125 articles on Latin American Business History were published in four leading business history journals from 1950 to 2021. This accounts for barely 2.42 percent of the total, clearly pointing to its marginality.Footnote 5

The available data yields several other—albeit contrasting—findings. It confirms that business history has expanded even more in scope in the past fifteen years to include different world regions, bringing a whole new cluster of empirical settings. Yet, when it comes to Latin America, a look at first author’s institutional affiliation reveals that most of those articles have been written by scholars based in the United States (thirty-six) and the United Kingdom (eight), with Mexico showing up only in third place (six).

So, while several signals point to a more multicultural business history setting—which should be acknowledged—some critical aspects remain unaddressed. How can we reinterpret and overcome the perpetuation of some hierarchies in our field? What are possible key insights from embracing an even more inclusive, global, and pluralistic vision of business history? My proposition is that these issues can be reinvigorated as part of a broader epistemological debate on humanistic and social sciences. Though some epistemological debates are confronted or have even changed the face of most branches of historical research, I propose that business historians have lagged.Footnote 6 This brief article considers possible alternatives from embracing even more diversity and complexity in our field from a Latin American perspective.

World Segmentation into Areas

Which categories are we using to organize business histories around the world? Yes, dividing the globe into meaningful units as a framework to narrate the world’s past is as old as historiography itself.Footnote 7 However, tracing the origins of these partitions and segmentations that continue to shape today’s academic research proves relevant when thinking about potential futures for business history. Why? Every division involves issues of exclusion and inclusion that are neither trivial nor accidental.

The critical observation that adding data on distant (geographically and otherwise) settings is not tantamount to expanding the geographic boundaries of our field has been clearly expressed in an interpretative essay written by Gareth Austin, Carlos Dávila, and Geoffrey Jones.Footnote 8 These authors proposed that the business history of Latin America, Asia, and Africa—despite recognizing the significant differences among countries and within regions in every country—can contribute something more radical and intellectually more challenging for the business history agenda. They note that businesses in these regions have faced common challenges since their contexts differed from those of developed markets. In particular:

-

• These countries were on the wrong side of the Great Divergence—the opening or rapidly widening gap between “the West and the Rest” in the nineteenth-century—and have been trying to catch up ever since.

-

• These regions endured long eras of foreign domination or even included countries that escaped formal colonialization only to experience prolonged periods of constrained autonomy.

-

• These economies had extensive state intervention, faced institutional inefficiencies, and were besieged by extended turbulence.

I agree that with linear approaches to capitalist development not every market experience fits into existing frameworks, and many can be considered anomalous, exotic, and so on. Labeling matters too; in particular, the issue (or the question) of which criteria prevail to define and name the heterogeneous spaces we study.Footnote 9 It is valuable, then, to debate the categories we use to classify business histories worldwide and, more importantly, how they can be used analytically. For example, the Emerging Markets diffuse category intends to show the contours of what has been described as an increasingly multipolar world.Footnote 10 The use of the controversial “global South” label has become widespread recently in research.Footnote 11

These meta categories are not new at all. There has been a tendency to frame all kinds of research on empirical phenomena within vast sets of areas otherwise—or simultaneously—referred to as “the developing world,” “non-Western” economies, “the periphery”—a term derived from dependency and world-systems theories—Footnote 12 or “third world”—the now-outdated notion produced by the practices and discourses of development after the Second World War.Footnote 13 Interesting for this reflection—even considering the variety of meanings attached to those terms—is the fact that almost all of them highlight one set of hierarchies, sometimes perpetuating them instead of offering solutions to overcome them. Most of them indicate binary frameworks, and we know that empirical realities have always been considerably more complex than that.Footnote 14 I also wonder if the need to name them as “emerging” or “non-Western” or to use more defined political and geographical categories such as “African” or “Latin” suggests that they are knowable and intelligible only through the discourse of the center? Or, can they be known on their own terms? These are our challenges.

Of course, you may be thinking that these partitions sometimes are simply a necessity or a mental routine that requires each other to exist. But the question underlying such required historical and spatial specificity is: Can we entirely rid ourselves of Eurocentric bias or Euro-American perspectives in order to incorporate the knowledge of others? Many scholars have reflected on the late fate of area studies in the “center” (mainly in the United States and Europe) and how—among other issues—they were isolated in separate enclaves and viewed as experts on the exotic “other,” and when related to Latin America, on backwardness or crony capitalism.Footnote 15 As Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo noted, over the course of the twentieth century, Latin America became another name for underdevelopment, the example of the world’s experiments in modernization par excellence, and the enduring triumph of backwardness—either because these countries failed to become new nations like the United States, or because of their endemic violence and inability to overcome “path-dependent” sins against modernization.Footnote 16 Yet, these statements, derived from post–World War II Modernization Theories, took for granted and reinforced the existence of a Latin part of the Americas—traditional, Catholic, patrimonial, backward, messy, violent—where new social engineering could be applied, turning Latin America—as a result—into a coherent geographical and cultural category.Footnote 17 I will further elaborate on the open meanings of Latin America as a category. But, for now, what I want to underscore is something else: turning to multiple versions of Business History could be problematic if it is assumed that it solves the problem of Eurocentrism or Western centrism per se (or by ignoring it).

What other kind of framework could we imagine?Footnote 18 A first step, that is not totally original but can have a significant impact, is asking about and understanding the distinctive features of the business culture in a given place (it can be a Latin American country or a region) described by historians who free themselves of some of their preconceptions about the “normal” path to development or about “normal” entrepreneurial and managerial behavior, to use here an assertion that was expressed by Rory Miller almost twenty-five years ago.Footnote 19 I also think—as part of a personal reflection about asymmetries and power in academic research—that we need to genuinely (not rhetorically) “shake off any inferiority complexes regarding the dominant theoretical paradigms from the English-speaking world,” a textual claim that Paloma Fernández Pérez and I wrote in the introduction to a comparative historical study of family businesses in Latin America.Footnote 20

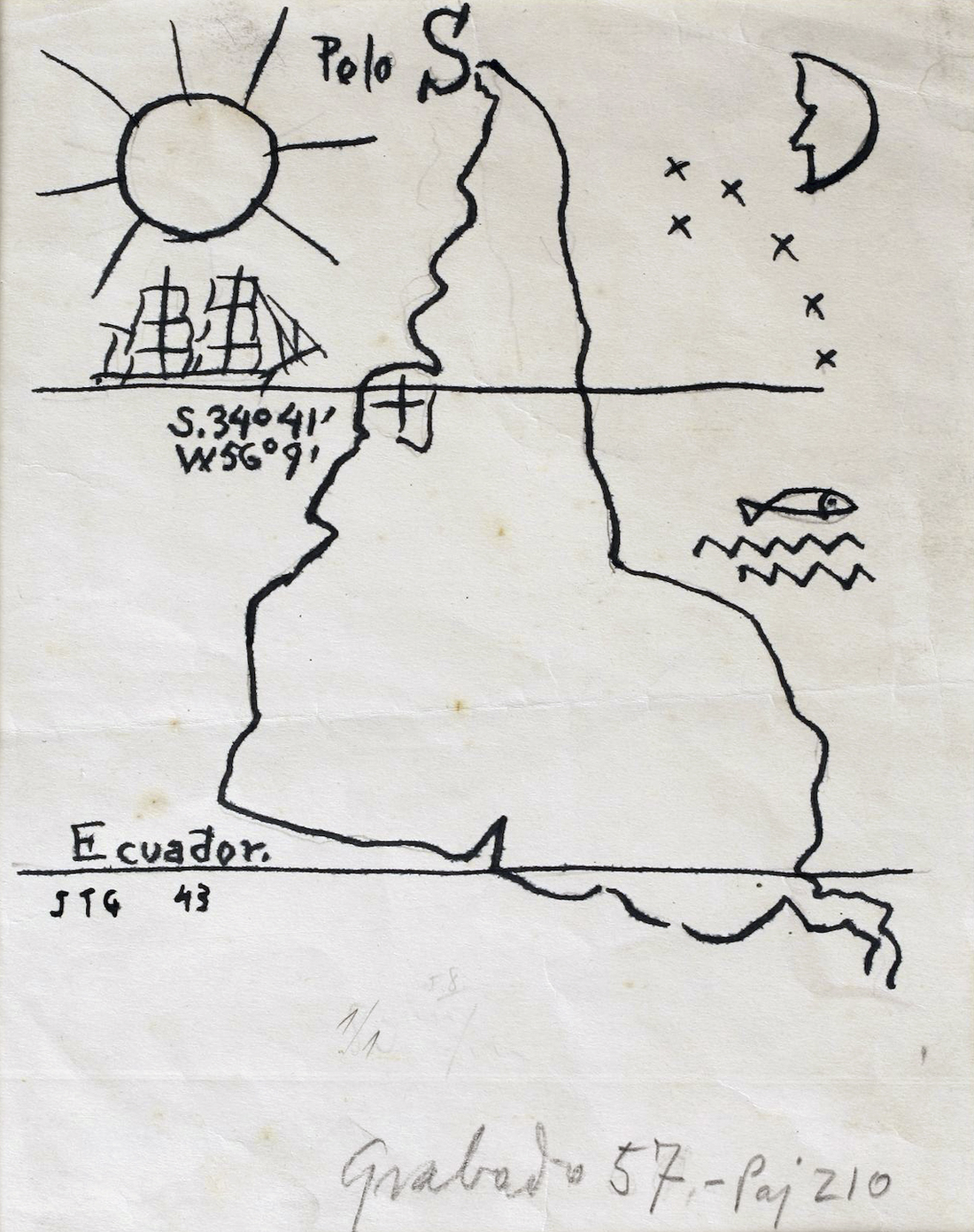

As a result of this call to critically use spaced classifications as analytical tools, questions emerge: Is there something, we can call Latin America? Is there a distinctive Latin American business history to be written? Latin America has thought about and seen itself based on its articulation with a more extensive world.Footnote 21 Consequently, there has been a permanent tension in Latin American self-reflections, and this observation goes well beyond economic or business histories. An early example that comes to mind to illustrate this argument is taken from the arts. In 1935, la Escuela del Sur (the School of the South) and its creator, Uruguayan painter Joaquín Torres-García, published a manifesto accompanied by the first version of his seminal Inverted Map drawing. Both reversing geographic cartography and repositioning a single and autonomous Latin America, by itself, at the top of the map, Torres-García stated, “Nuestro Norte es el Sur” (Our North is the South)—a passionate message veiled in a sociopolitical statement to invert the traditional artistic hierarchy, which at the time was dominated by European art (Figure 1).Footnote 22 Thus, Torres-García formulated a sort of counter-history of art, rejecting the teleology ingrained and exported through historiographies universalizing the West’s own local artistic works.Footnote 23

Figure 1. Inverted Map, by Torres-García.

Joaquín Torres-García, América Invertida (Inverted America), 1943, ink on paper, 22x16 cm.© Fundación Torres-García, Montevideo.

But how is this connected with possible means to do Latin American business history today? To answer these questions, let me now try to condense three ongoing parallel debates.

Latin America as an Idea

The first debate revolves around the meanings of Latin America as a concept. Over the past decades, the usefulness of the term Latin America itself has been strongly questioned, especially in Spanish and Portuguese.Footnote 24 In English, the idea of Latin America has not been criticized much, aside from very much historicizing the old and new imperial connotations of the term and the Cold War origins of Latin American Studies in the United States.Footnote 25

We know that “Latin America” is a modern concept—the term itself did not show up in spoken vernacular Spanish and Portuguese until recently.Footnote 26 Also, “Latin America” refers to history, language, and culture. It constitutes a lasting confirmation of racial beliefs.Footnote 27 Thus, as a modern, highbrow conjecture about culture and indeed about race, the term Latin America fails to designate a rapidly changing reality.Footnote 28 In a nutshell, as Walter Mignolo and Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo have remarked, the term carries the heavy load of excluding African American and Indigenous populations and should be used cautiously today. Hence, several authors agreed on one point: Latin America is politically, morally, and culturally troublesome, but it nonetheless remains a recognizable—albeit challenging—term.Footnote 29

What should we do with it in historical analyses? As Latin America business historians, we have not addressed much in this debate. While recognizing the shortcomings and limitations of the term, I would say that we have used it strategically, and we have left it to each scholar to clarify and explain any specificities or “their terms of its existence.”Footnote 30 This, in turn, implies paying close attention to local traits and rejecting unsustainably broad generalizations while indicating the region’s many similarities in terms of political, economic, and social structures.

As noted in the introduction to Historia Empresarial de América Latina, we may talk about Latin America’s business history, but not in the sense of a notion that simplifies disparities and differences.Footnote 31 Rather, each study should present specific cases or research problems that are bound together by the specific features of the region’s business system, while underscoring the differences that characterize each country or region (and regions inside a country).Footnote 32 Thus, a strategic analytical exercise should unfold, as suggested by seminal books on Latin America’s economic history, such as those written by Rosemary Thorp, Victor Bulmer Thomas, and Luis Bértola and Antonio Ocampo.Footnote 33 They all took different paths to discuss a region with historical (economic, political, and cultural) specificities while challenging themselves to capture the significant disparities inside this community of twenty countries.

As those authors explained, Latin America’s history is filled with economic ups and downs, with thriving periods followed by stagnation or steps back, with times of institutional instability, and with significant changes in development models. However, the boundaries of Latin American states—although often the source of interstate conflict and still not entirely settled—have changed much less in the past 150 years than frontiers elsewhere.Footnote 34 Finally—and this is very important—its history is plagued by inequalities that not only reflect the well-known inequality inside every individual country but also show the staggering differences between Latin American nations and the world’s economic leaders. Most of the topics addressed by works focusing on the whole of Latin America stem from this: coloniality, exploitation of natural resources, development patterns, stop-and-go progress, and inequality.

Interestingly, the strategic and vague use of the term Latin American can be seen as another point of convergence and can offer then a fruitful path. As Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo considers in his passionate conclusions, there is a growing tendency to use the term Latin America as a malleable vessel “ready to be filled with interesting, important, more-than-national histories, and not only Latin American ones.”Footnote 35 However, other voices have proposed that training and placing truly more-than-national historians in Latin America—and, I must alert you, this is a self-critic present in all reflections on historiographical balances—has proved to be a “challenging conundrum.” And this is the second debate I want to discuss briefly now.

Global History: Any Room for “Latin America”?

This second discussion can be articulated with a straightforward question: Is there any room for “Latin America” in the field of global history? As we all know, the global history field has been thriving for over two decades; however, unlike Europe, the United States, and Asia, which have witnessed a true “boom” in this area, there has been no such significant development in Latin America.Footnote 36 Several global historians have been trying to explain why historians from (and studying in) Latin America have been disinclined to engage with global history (and one may ask, with global business history).Footnote 37 According to Matthew Brown—and I agree—one of the causes for this distrust is the perception shared by many Latin American historians that global history has been hijacked by studies on some areas, which consequently imposed their own historical and political agendas, thus creating frameworks, spatial segmentations, periodization, and focal points that hinder the incorporation of Latin American History.

Complementary explanations can be found in the denounced unilateral direction of knowledge flows. While most European scholars publish in or at least read English, colleagues in the Anglo-American world rarely reciprocate. This asymmetry has caused resistance in several Latin American and European academic environments, where scholars fear that their work is downgraded.Footnote 38 Indeed, even the English-speaking addiction to Latin America as a unified concept only reinforces the marginality of the Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking worlds. Thus, speaking about Latin America has often meant “looking down” on any knowledge produced in Spanish and Portuguese.Footnote 39

And thus, we come to the issue of the current Anglophone mono-linguicism of these disciplines—both global history and mainstream business history. Here, I must admit that many non-English colleagues reacted to this observation by explaining that English is academia’s lingua franca; and indeed, it is. Sometimes it is even misconstrued as a call to remain isolated and not to publish in English. This is not, I want to stress, the essential point I am trying to make,Footnote 40 which hinges on the direction of knowledge flows. This raises an epistemological problem that touches the foundations of any historical (and social science) discipline. A brief reflection on the third debate is necessary then to expose or discuss the perpetuation of hierarchies in our field for a deeper understanding.

“I Am Where I Do?” Footnote 41 Geopolitics of Knowledge

The third debate is closely related to calls for the “decolonization” of social and humanistic sciences. Without wishing to delve into a debate with multiple sides, I want to highlight how these voices have raised thought-provoking questions about the global and national politics of knowledge and the structures of knowledge production. Even in management and organizational studies, there have been recent demands to use critical theoretical frameworks for the construction of more plural academic fields.Footnote 42 Latin Americanists working on social sciences and cultural studies have been using the language of coloniality/decoloniality extensively to propose new ways of understanding Latin America’s historical and contemporary relationships with the rest of the world.Footnote 43

Historians, though, have been more reluctant to do so. They dislike some of these statements for their “crude ahistoricism”Footnote 44 and for the over-simplifying arguments used to advocate, for example, that the social sciences commonly practiced in universities around the world are only a product of “the West.” I agree with some of these critics. For example, it is one thing to reflect on the uses and abuses of Eurocentric concepts or Euro-American perspectives in social and humanistic sciences—in Latin America or other geographies—and quite another to uphold the ahistorical formulation of supposedly pure and native models.

However, instead of dismissing this debate entirely, it might prove useful to look into some of its insights. The geopolitics of knowledge is appealing. It is also part of this modernity/coloniality/decoloniality project fostered by Latin American scholars,Footnote 45 and thus it is included among the so-called epistemologies from the South.Footnote 46 In essence, and despite the risk of oversimplification, this concept asks, “By whom and when, why and where is knowledge generated”?Footnote 47

An example of how to revisit old debates from new angles is provided by a recent book called The World That Latin America Created, written by Margarita Fajardo.Footnote 48 As the author states:

Through the story of cepalinos [referring to the Economic Commission for Latin America school of thought; or CEPAL, the Spanish/Portuguese acronym] and dependentistas, this book stands not only as a contribution to writing more inclusive or “wider and deeper” global histories but also as a challenge to narratives of the universal triumph of the global North’s economic ideas and institutions.Footnote 49

Indeed, she ultimately argued that cepalinos—since their project emerged from the global South and expanded to the rest of the world—effectively inverted the traditional directionality of world-making. From that perspective, Fajardo looks at the construction of a development worldview from the intersection of Santiago and Rio de Janeiro, from Mexico and Havana, rather than from Washington, London, or Moscow.

Thus, the focus on the geopolitics of knowledge brings an opportunity not only to better capture the historical reality of a region—Latin America—marked by economic and institutional turbulence, imperialism and colonialism, sharp inequalities, racism, and different sorts of exploitation but also to reflect on and gain a deeper understanding of the realities and diverse institutional and historiographical paths in our field. How? This concept raises our awareness of the importance of situating and historicizing knowledge production.Footnote 50

At this point, it may be convenient to remember that, in most countries in Latin America, Business History has a marginalized position inside economic history or management studies and that its institutionalization remains low. There is no association that brings business historians together on a national or regional scale.Footnote 51 In an opposite direction, networking and collaborative projects have played an important role and underlie many of the achievements and advancements in the production and dissemination of the discipline in the region, especially from the 1990s to date.Footnote 52

It is worthwhile to take this perspective to reexamine the interviews that Mario Cerutti conducted in 2017 with three field leaders:Footnote 53 María Inés Barbero (Argentina), Carlos Marichal (Mexico), and Carlos Dávila (Colombia); or the self-reflection made some years before by Mario Cerutti himself or Rory Miller.Footnote 54 In all five cases, their views prove fascinating and shed some light on the development of the field in Latin America—especially considering their heterogeneous trajectories—while illustrating the relevance of asking by whom, when, why, and where knowledge is generated. For example, looking back on his beginnings as a researcher of British firms in the region in the 1970s, Rory Miller asked himself, “Were we writing ‘business history’ in the North Atlantic/Harvard sense?”Footnote 55 María Inés Barbero, from a different vein, remembers the difficulties in accessing bibliographic resources even in the early 1990s. She recalled that she was only able to photocopy, for example, the works of Alfred Chandler and other key mainstream authors when she traveled to Italy, as these materials were unavailable in Buenos Aires.

Without falling into simplistic approaches, since academic networks, collaborative projects, and exchange programs have shortened distances, I would like to invite you all to take a closer look at the site of enunciation and knowledge location when analyzing what has been written about a topic and how. This may help explain in a more empathic way why business historians have not always been asking similar questions in different regions—or even speaking the same theoretical languages.Footnote 56 It also can help to understand why sometimes it is necessary to adjust categories and methods to destabilize some entrenched teleologies of the Euro-American economic and business experiences.

I can extend this analysis even further to mention—briefly—the critical access to archives. This is not exclusive to Latin America, as these asymmetries are reproduced elsewhere. But, as we know, the lack of written archival sources can be a constraint for the growth of business history, due to the poor tradition of holding and opening corporate archives.Footnote 57 Hopefully, some initiatives have been launched to reduce this problem, although there is still a long way to go.Footnote 58 Conversely, the scarcity of corporate archives has encouraged oral history projects that are trying to help fill this void. I collaborated with the first version of the now called Creating Emerging Markets (CEM) project at Harvard Business School. I had the opportunity to launch the pilot project in 2008–2009 as a collection of audio interviews with prominent business leaders in Argentina and Chile. CEM has grown into an archive of over 170 lengthy audio and video interviews with leaders or former leaders of businesses and NGOs from more than 25 countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, where the collection now features 65 interviews.Footnote 59 What is more important: these interviews show how oral history offers a nuanced understanding of business practices in Latin America. But more needs to be done. Oral history and other methodological strategies to identify atypical primary materials are important tools to study underrepresented or marginalized groups, to challenge grand narratives, or—as others have noted—to undercover the unconventional histories of capitalism.Footnote 60 But what separates conventional from unconventional?

Business Responses (History) of (and in) Troubled Contexts

Based on the attention paid by scholarly knowledge, it is safe to say that entrepreneurs (individuals), entrepreneurial families, business groups, and business interest groups have been the conventional entrepreneurship agents in Latin America, and therefore they have received plenty of attention. Together with the heated debates on foreign investment and multinationals, as well as the role of the state, and state-owned companies; all these topics have garnered most of the academic attention.

This agenda is much connected with the Alternative Business History proposal mentioned before, since it claims that distinctive business responses arose in those areas because of unique challenges. In those areas of the world:Footnote 61

-

• Entrepreneurs mattered more than managerial hierarchies.

-

• Immigrants and diasporas accounted for critical sources of entrepreneurship.

-

• Illegal and informal forms of business were common.

-

• Diversified business groups rather than the M-form became the primary scheme for large-scale business.

-

• Corporate strategies to deal with turbulence proved essential.

I would like to linger on this last point to reconnect with the discussions mentioned above. For the great “rest of the world”—and here I am not referring to the concept of uncertainty that has received a great deal of attentionFootnote 62—turbulence and instability have been more the norm than the exception. But again, what is normal, for whom, or by what standards? And here may lie a strength for enriching not only current narratives but contributing to contemporary pressing issues, for example, on how businesses deal with inflation or challenges in a new era of deglobalization. For that, the question itself is not only to identify the commonalities but the context-specific business responses to these more complex and unstable contexts. Of course, you may be thinking that we, as historians, know that business decisions are not made in the void of perfect markets but are subject to a context that results from previous events, and while each actor has an expected or desirable outcome in mind.Footnote 63

In many scholarly discussions, instability is not the norm, but the exception; and theoretical perspectives emphasize the benefits of stability. Plus, current business literature offers no consensus on why some business agents have endured longer than others in equally troubling environments. Business historians are well equipped to provide a richer explanation of those big questions. For example, a sudden change in economic conditions or a new political regime can undermine social capital and the rule of law. But, at the same time, periods of disruption can be an opportunity for outsiders or can bring the need for adjustments and fruitful reinventions. Going further, such terms—defined by the outcome, not the process—hardly capture the moving and nonlinear reality of developing a business in a volatile environment.

Let me provide an example that is a bit sad for me. A noteworthy feature of Argentina was and is inflation.Footnote 64 In 1976 annual inflation rate reached 438 percent, and it achieved an all-time high in 1989 at 3,058 percent. Inflation had fallen back to “only” 12 percent in 1992, and price levels stabilized during the second half of the 1990s. But by 2002, inflation was back up to 31 percent, before halving by 2007, and last year it topped 50 percent. That means that inflation has been the norm and not an exceptional circumstance, or a specific disorder.Footnote 65 As an article in the Washington Post recently expressed it: “Worried about inflation? In Argentina, it’s a way of life.”Footnote 66 Chronic high inflation affects the way Argentines spend, save and think, and make business!Footnote 67 It also explains why Mafalda, the most famous and popular Latin American comic strip in the world, is alive and retains its popularity for so long (Figure 2).Footnote 68

Figure 2. Mafalda comic strip.

“I don’t love my inflation. Do you?” Quino, “Mafalda” (August 1971).© Joaquín Salvador Lavado (Quino).

In this unstable setting, long-term planning often seemed futile, and promoted the proliferation of opportunistic behaviors. Inflation management and short-term policies characterized businesspeople’s experiences.

Here are some quotes provided by the CEM database that illustrate my argument for the need for even more context-specific questions and explanations. Rodolfo Viegener, president of the plumbing manufacturer Ferrum remembered: “I started working in 1962, and, for 30 years, until 1992, my entire experience revolved around a high-inflation setting.”Footnote 69 He later added, “I focused strictly on the short term, adjusting to short-term conditions. I just thought, ‘I just have to get through today; tomorrow we’ll see.’” Adapting to changing environments—and learning how to play to your favor with the redistributive game—seems to have been a key factor for business survival in Argentina. Someone else stated: “My career was based on watching reality very closely at all times and adjusting very quickly to each setting, changing radically.”Footnote 70 Tomas Hudson, who led the Argentinean affiliate of the British chemical company ICI, remarked: “But the notion of strategy was put away, right? In the most critical times, it was just next month.”Footnote 71 Nonetheless, findings provided by business historians have challenged the generalization/dictum indicating that the interaction of firms with their environment ultimately determinates firms’ fate.

In fact, firms have also been highly conditioned not only by external or exogenous forces but also by individual firms’ backgrounds, effective assembling and mobilization of financial resources, business families’ and leaders’ own goals, and even reputational factors, given the owner-intensive nature of most of these enterprises—another regional trait.Footnote 72

Meanwhile, other studies have identified other firms’ strategies to face economic, institutional, and political turbulence.Footnote 73 Business historians have stressed the relevance of nonmarket responses: from internalizing different functions to a greater reliance on interpersonal trust and networks, or the development and uses of “contact” capabilities. The importance of these practices (personal or corporative) has varied through time, depending, for example, on the strength of the states and the degree of politicization of markets. In addition, existing case studies suggest not only plural behaviors but also changes over time, with examples of entrepreneurs or firms switching—following Baumol categories—from productive and innovative to rent-seeking behaviors.Footnote 74

Hidden Opportunities

Exploring these nonlinear and even conflicting trajectories of the margins would enable us to reevaluate our shared assumptions about the nature of businesses in more troubled contexts such as Latin America but also what we, as business historians, all of us, ought to include in our scope of inquiry. I would like now to reengage again with previously mentioned debates and reassess what three former chairs of the Latin American Studies Association (LASA)—namely, Sonia Álvarez, Arturo Arias, and Charles R. Hale—referred to as an alternative form of Latin Americanism for the twenty-first century. They proposed reviewing and decentralizing Latin American studies—a notion that they viewed as a metaphor to signal the effort to move our thinking beyond Western and Eurocentric conceptualizations.Footnote 75

Reviewing Latin America would mean—the authors said—not only asking what Latin America means, which I have already discussed, but also including more voices that would bring more meanings. With this premise in mind, I will now briefly refer to some perspectives that would enrich our research agenda and, in this way, our discipline. Before I start, and as a clarification, the production of knowledge about Latin American countries has become deeper and geographically broader over time, and these contributions have been summarized in various historiographical essays.Footnote 76 However, there are still many challenges—theoretically and empirically—to understand in all their complexity and diversity, development, organization, management, and operations of businesses (or empresariado) in Latin America.Footnote 77

Plurality is lacking. Identities are missing in our field. As mentioned before, “Latin America” came into wide use only recently; meanwhile, Indigenous peoples inhabited the Americas for thousands of years before the European conquest. We need to explore the Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems.Footnote 78 Business history literature has ignored and remained silent about them. Business history has also largely neglected the African and East Asian Diasporas since most attention has been directed to European flows.

Until very recently, gender perspectives have also been less present in the Latin American business history literature, dominated by the more recognized roles played by male entrepreneurs, entrepreneurial families, and business groups. In general, female entrepreneurship has been, until very recently, a missing topic in Latin American business history. And recent research has shown, discrimination and lacking equal economic opportunities have significantly curtailed women’s effective involvement in business development—a topic that business historians are only starting to address.Footnote 79 There are other neglected groups and less conspicuous businesspeople who also deserve our attention, such as those who represent nontraditional businessesFootnote 80 or alternative forms of capitalism, social enterprises, cooperatives, or empresas recuperadas, the worker-recuperated enterprises, which is a hybrid social economy organization.Footnote 81

Microenterprises, small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), are key players in Latin America—so much so that they account for over 90 percent of all Latin America’s businesses and provide jobs for nearly 67 percent of the region’s working population.Footnote 82 However, and with few exceptions, studies on SMEs from a historical perspective have proven infrequent and significantly fewer than those focusing on large companies. For some scholars, of course, it is largely due to the difficulties in accessing sources and the fact that the information is greatly scattered, but also I think it is permeated by narratives that privilege the study of Chandlerian firms and the evolution of big business.

Furthermore, few scholars have adopted an alternative approach that requires shifting attention from formal business systems to informal business practices. This is remarkable since the informal economy in Latin America accounted for 34 percent of its average gross domestic product from 2010 to 2017—more than in any other region in the world. A total of 140 million people work in jobs involving social vulnerability, limited rights, and precarious conditions. According to the International Labour Organization, this number translates to roughly 50 percent of the overall employment in Latin America. It is a little below the global average but more than twice as much as in developed regions.Footnote 83

I will stop here. But I just want to add that I believe that a more intensive engagement with the countries of the “South”—even acknowledging the limits of this concept—can make more relevant our research to a wide range of scholars interested in the institutional foundations of capitalism and its divergences (in plural), ethics, organizational studies, and those who are interested in explaining why and how entrepreneurship differs among countries, regions, and time periods, and why and how these matters.

Epilogue: Embracing Complexity and Diversity

In any historiographical practice, it is not that easy to implicitly or explicitly overcome the various hurdles imposed by Eurocentrism or Euro-American perspectives.Footnote 84 It then becomes a matter of finding ways to write business history—in my case, I am advocating from a Latin American perspective—maintaining the due methodological rigor, historical depth, and broad empirical and theoretical bases, while also reviewing and adjusting research questions, categories, and methods to the region’s multiple, asymmetric, and changing historical situations.

But Latin America (or any other place) ought not to determine per se our historiographical topics. The topic should define whether we speak of Latin America or not, and if so, how.Footnote 85 This is what I have tried to emphasize here: proposing to decenter the analysis of Latin America. And in this process, it would be important to add—at least for the sake of discussion—epistemological analyses and concepts, such as the geopolitics of knowledge, that have originated in and from the “margins.”

Business historians, of course, will continue debating about the boundaries and identities of the field, and some insights from these calls to sensing the world as pluriversally constituted can contribute to enriching focal points that have been hindering the incorporation into the mainstream of the “other” stories.Footnote 86 I hope that these reflections can help enrich preexisting conversations and have pointed—hopefully—to some key insights to embrace an even more inclusive, global, and pluralistic vision of business history. The timing for embracing this conversation is good. Beyond any shadow of a doubt, there is change in the air.

More than fifty years ago, Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges made a statement that is still quoted with fury and passion—and that encapsulates part of what I wanted to share with you today. He said, “Debemos pensar que nuestro patrimonio es el universo” (The universe is our birthright). Let me paraphrase the rest of this quote: “We can take on all … subjects …, handle them without superstition, and with an irreverence which can have, and already does have, fortunate consequences.”Footnote 87