Introduction

While always an issue of concern, particularly since deinstitutionalization in the UK (Thornicroft, Reference Thornicroft2006), violence, hostility and discrimination against people with mental health problems have been increasing in prominence in international research and policy over the last 10 years. One recent study investigating the social effects of the 2008 economic crisis on people with mental health problems in 27 European countries found that ‘times of economic hardship may intensify social exclusion of people with mental health problems’ (Evans-Lacko et al. Reference Evans-Lacko, Knapp, McCrone, Thornicroft and Mojtabai2013, p. 1). The UN Human Rights Council's ‘Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health’ is clear that ‘persons with psychosocial disabilities continue to be falsely viewed as dangerous, despite clear evidence that they are commonly victims rather than perpetrators of violence’ (UN Human Rights Council, 2017, p. 7). Accordingly, the report recommends that States ‘take policy and legislative measures on the prevention of violence in all environments where people live, study and work’ (UN Human Rights Council, 2017, p. 20). Therefore, violence, hostility and discrimination against people with mental health problems have been prioritised as a human rights issue of global concern.

This paper presents a body evidence on the topic from the UK deriving from the scoping review stage of a larger service user researcher-led (Beresford & Croft, Reference Beresford and Croft2012) qualitative study set in England entitled: ‘Keeping control: Exploring mental health service user perspectives on targeted violence and hostility in the context of adult safeguarding.’ The study has been designed in the context of State legal and policy reforms in the UK concerning adult safeguarding (DH, 2014). These reforms determine that adult safeguarding should be less reactive and mechanistic, and more about achieving the best outcomes for the individual concerned and responsive to the person and their specific circumstances. Policy implementation work found that ‘using an asset-based approach to identify a person's strengths and networks can help them and their family to make difficult decisions and manage complex situations’ (LGA, 2013). In the UK ‘adult safeguarding’ is defined as: ‘working with adults with care and support needs to keep them safe from abuse or neglect. It is an important part of what many public services in the do, and a key responsibility of local authorities. Safeguarding is aimed at people with care and support needs who may be in vulnerable circumstances and at risk of abuse or neglect. In these cases, local services must work together to spot those at risk and take steps to protect them’ (DH, 2014).

Sin et al. (Reference Sin, Hedges, Cook, Mguni and Comber2011) use the term ‘targeted violence and hostility’ against disabled people, which in UK legal terms is categorised as ‘disability hate crime’. In the UK ‘hate crime’ is defined as ‘any criminal offence, which is perceived, by the victim or any other person, to be motivated by a hostility or prejudice based on a personal characteristic.’ (HM Government, 2013). For the purposes of the larger study, the ‘personal characteristic’ is having a mental health problem (also defined as a disability in the UK Equality Act 2010). It is well documented that disabled people, particularly people with mental health problems, are at higher risk of being victims of targeted violence and hostility, although effective evidence-based prevention and protection strategies remain lacking (Emerson & Roulstone, Reference Emerson and Roulstone2014; Mikton et al. Reference Mikton, Maguire and Shakespeare2014). This paper will largely use the terms ‘hate crime’ and ‘targeted violence and abuse’ to describe the incidents reported in the studies, with the acknowledgement that victims may not describe or recognise their experience as a disability/mental health related ‘hate crime’, and professionals may not classify or recognise it as such. The discourses on adult safeguarding and risk, mental health and ‘disability hate crime’ have appeared to remain largely separate in research, policy and practice, and overall, mental health service user experiences remain under-researched. The larger study, of which is scoping review is an element, aims to address this situation.

Scoping review questions and objectives

The scoping review addresses the core components of the main study inquiry and builds on the literature review on risk and safeguarding in UK adult social care Mitchell et al. (Reference Mitchell, Baxter and Glendinning2012). Among other things, they found that there were a significant gap in the UK primary research evidence on mental health service users’ views and experiences of risk and safeguarding.

The main aim is to ‘map rapidly the key concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available’ for the UK (Arksey & O'Malley, Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005, p. 194).

The scoping review research questions focus on what is known from the existing UK literature about the following:

-

a) mental health service user concepts and experiences of mental health-related targeted violence and hostility (‘disability hate crime’), risk, prevention and protection

-

b) where mental health service users go to get support if they are frightened, or have been victims of, targeted violence and hostility because of their mental health problem or psychiatric status (help-seeking behaviour)

-

c) responses of adult safeguarding agencies, mental health services and other organisations to mental health-related targeted violence and hostility (‘disability hate crime’) against people with mental health problems because of their mental health problem or psychiatric status

-

d) the key concepts underpinning the literature in the research area and the main sources and types of evidence available

-

e) what and where are the main gaps in the literature

The objectives of the scoping review were to:

-

• systematically search for peer-reviewed journal papers and ‘grey literature’ that addresses the key research questions;

-

• assess the types and quality of the included literature (as a determinant of the strength of the reported evidence);

-

• conduct an analysis and thematic synthesis of the literature identified to address the key research questions and to inform the larger research study investigation;

-

• assemble an evidence base on adult safeguarding that focuses on mental health service user experiences and perspectives on mental health-related targeted violence and hostility, risk management, help-seeking, prevention and protection.

Methods

The six-stage methodological framework for scoping reviews, as developed by Arksey & O'Malley (Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005) and further refined by Levac et al. (Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien2010), was used to conduct and structure the literature review. The six stages are as follows:

-

1. Identifying the research question

-

2. Identifying relevant studies

-

3. Study selection

-

4. Charting the data

-

5. Collating, summarising and reporting the results

-

6. Consultation with expert/stakeholder advisory group

Peer-reviewed English language journal papers were identified via the relevant health and social care databases available at Middlesex University through a keyword search using terms relating to mental health, adult safeguarding, service users, disability hate crime and targeted violence and hostility. In total, seven databases were searched for the years 1990–2016: CINAHL; PsycINFO; Medline; Social Care Online; Emerald; BNI; Cochrane reviews.

Searches for English language ‘grey literature’ was also conducted via online searches (Summon, Google Scholar, Open Grey, relevant UK government websites and organisational websites such as Mind, Mental Health Foundation, Shaping Our Lives, National Survivor User Network, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Victim Support, SPRU, NIHR SSCR, Disability Archive UK, SCIE, EHRC, BASW), contact with topic experts, key organisations and via team and advisory group member networks.

Hand searching of key journals (i.e. The Journal of Adult Protection) and examinations of article reference lists (particularly previous literature reviews) was undertaken.

The search strategy included both primary and secondary search terms (see Box 1: Primary research terms).

Box 1. Primary search terms

In order to search for mental health service users’ experiences of hate-crime, targeted violence and hostility the following search terms were used:

-

mental* OR mad* OR psychiatr* OR disab

-

AND

-

service user OR survivor OR consumer OR client OR expert by experience OR lived exper* OR patient

-

AND

-

views OR experience OR perspectives OR narratives

-

AND

-

violence OR abuse OR hate crime OR hostil* OR danger* OR risk* OR victim* OR crime OR bully* OR harass*

-

Secondary search terms

In the context of the searches retrieved through the primary search terms mental health service users’ help-seeking behaviours and their experiences of support and safeguarding were searched for using the following search terms:

-

adult safeguard OR vulnerable adult* OR protect* OR safe* OR prevent* OR peer support

-

OR

-

resilience* OR coping OR help* OR managing OR protect* OR support

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to eliminate studies that did not answer the research question and to ensure a consistent approach between scoping team members (see Box 2: Inclusion and exclusion criteria). Rather than adhering to a hierarchy of evidence approach, based on methodology, we included empirical studies (quantitative and qualitative) most likely to answer our research question (Aveyard, Reference Aveyard2007). However, the methodological quality of included studies was assessed by their using appropriate critical appraisal (CASP) checklists, which are series of questions designed to help reviewers interrogate the quality and reliability of various types of health and social care research, including qualitative studies (CASP, no date).

Box 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

a) Empirical studies conducted in the UK published in peer reviewed journals addressing the areas in the key research questions that have adults (18–65) and/or older people (65+) with mental health problems in their population.

-

b) Systematic reviews and other research reviews published in peer reviewed journals (or peer reviewed formats such as Cochrane or Campbell) addressing the areas in the key research questions that have adults (18–65) and/or older people (65+) with mental health problems in their population.

-

c) Conference papers addressing the areas in the key research questions published in peer reviewed journals or as ‘grey literature’ conference proceedings.

-

d) Mental health service user and survivor research addressing the areas in the key research questions published in peer reviewed journals or as ‘grey literature’.

-

e) Research reports or research reviews from key organisations working in the areas of mental health, hate crime and adult safeguarding, including user-led organisations and initiatives and voluntary and community sector organisations.

-

f) Individual narratives that do not use a recognised qualitative method.

-

g) English language publications.

-

h) Material published between 1990 and 2016.

Exclusion criteria

-

a) Duplications.

-

b) Non-UK studies.

-

c) Studies that do not include mental health service user experiences.

-

d) Studies concerning children and young people (0–18).

-

e) Studies concerning dementia or brain injury.

-

f) Commentary pieces.

-

g) Policy and guidance documents.

The study data were synthesised according to the scoping review ‘charting’ approach developed by Arksey & O'Malley (Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005). Their ‘data charting form’ the following key information was recorded about each study (see Table 1: Data charting form and numerical in-text reference key), including:

-

• Author(s), year of publication, study location

-

• Intervention type, and comparator (if any); duration of the intervention

-

• Study populations

-

• Aims of the study

-

• Methodology

-

• Key findings or important results

Table 1. Data charting form and numerical in-text reference key

A final column was added to the table in order to make additional comments or notes on the included studies (not included in Table 1).

A basic thematic analysis approach (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006) was used in order to identify, analyse and report patterns (or themes) that ran between the findings of the 13 finally included studies. The key stages in the thematic analysis were as follows:

-

1. Becoming familiar with the data.

-

2. Generating initial codes.

-

3. Searching for themes.

-

4. Reviewing themes.

-

5. Defining and naming themes.

-

6. Producing the report.

Using the data charting table, an initial list of key findings from each of the included studies was created. These key findings were grouped and merged together in order to develop a list of themes and sub-themes that mapped on to the scoping review's key research questions and objectives.

The findings sections of each of the 13 original papers were re-checked in order to ensure that extracts of data reported on the findings had not been missed thus further refining the emergent themes and sub-themes.

In order to avoid potential bias and subjective decision-making, the papers were re-read by another research team member in order to check whether the first reviewers’ interpretations or conclusions drawn from the included studies’ findings were aligned to the data presented in the original studies. The two reviewers were largely in agreement, and where there was some discrepancy in opinion, the differences were discussed and a mutually agreed position reached.

Findings

Search results

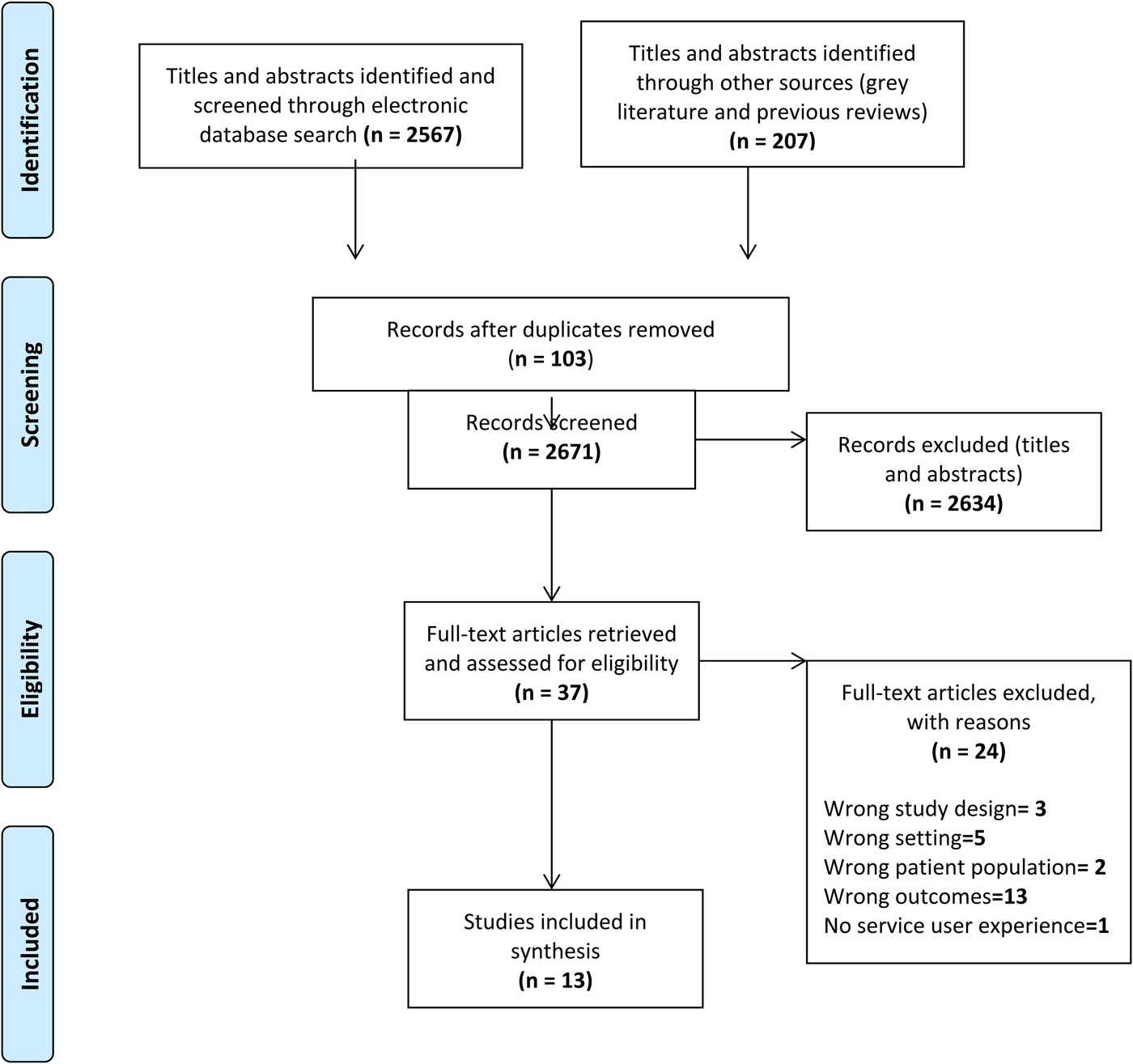

The database, grey literature and previous relevant literature review searches yielded a total of 2774 papers, reducing to 2671 after duplicates were removed. A total of 2634 articles were excluded as they did not meet inclusion. A total of 37 full-text copies were obtained and 13 relevant papers were finally included in the final scoping review (see Fig. 1: PRISMA flow diagram).

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow diagram: The study identification, screening and selection process.

The studies are numerically referenced in the text. The numbers and corresponding references are detailed in Table 1: Data charting form and numerical in-text reference key.

Seven out of the 13 studies included in the review explicitly focused on mental health service users’ experiences of hate-crime and targeted harassment, abuse, violence or victimisation (e.g. 1, 7, 2, 11, 13, 8, 5). In the six remaining studies, experiences of targeted violence or abuse were implicit within the wider studies aims and objectives. For example, three studies explored services users’ perceptions, experiences and involvement in risk management (6, 3, 10), two studies explored quality of life and social inclusion whilst living in the community (5, 12), one study explored experiences of discrimination (9) and one study explored experiences and perceptions of healthcare (4).

Over half of the included studies used survey methods (1, 2, 5, 7, 8, 9, 13). With the exception of one study, these studies employed mixed methods approaches by using a variety of qualitative methods alongside the survey data including, open-ended questions (9), focus groups (7), semi-structured interviews (1, 8, 2, 5) and field diaries (2). The remaining six studies employed a qualitative methodology using either semi-structured (10, 11) or in-depth interviews (4, 3, 6, 12). One study also conducted follow up in-depth interviews (6).

Three out of the seven studies that adopted a survey approach used standardised measures (13, 8, 5). Both Wood & Edwards (Reference Wood and Edwards2005) and Pettit et al. (Reference Pettitt, Greenhead, Khalifeh, Drennan, Hart, Hogg and Moran2013) used an adapted version of the Crime Survey for England and Wales. Kelly (Reference Kelly1999) used a structured questionnaire based on a quality of life profile that was developed and tested for the study.

With regard to sampling and recruitment, five studies recruited from community mental health teams (1, 12, 13, 8, 10), four from the community (3, 5, 2, 9), two from voluntary services (7, 11), one from general practices (4) and one from inpatient hospitals (6). A purposive sampling strategy was used to recruit participants in four studies (1, 4, 6, 10) whilst other studies used random (5, 8) and opportunistic sampling strategies (12). The sampling strategy was not reported in six of the included studies (3, 7, 2, 11, 13, 9).

All studies included people with experiences of mental health problems. One study also collected data on mental health professionals’ views (8), and in two studies data were collected on the experiences of those with learning disabilities as well as those with mental health problems (11), or encompassed within experiences of all victims from the general public (2). Furthermore, two studies directly compared the experiences of people with mental health problems with the general population (1, 8) and one study compared with students who had high life-style risks (13).

With regard to participant demographics, a majority of studies reported a near even spread of male and female participants (1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 13). In addition, in two studies a small number of the participant sample identified themselves as transgender (2, 11). The age range of participants for most of the included studies were between 18 and 70 years with the average age range in four of the studies being between 40 and 49 years old (13, 1, 7, 12), and between 20 and 29 years old in three of the studies (2, 4, 10). Those studies that reported participant's ethnicity, reported a majority of their sample as White British (2, 3, 6, 5, 7, 8, 9, 11, 13). Some studies did not give specific details on participant demographics, only stated how the participant sample were diverse with regard to, for example, age, gender, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation and disability (e.g. 2, 3 ,5, 12).

Review findings

Nature of incidents

The types of hate crime experienced by those with mental health problems included verbal abuse (1, 4, 5, 8, 9, 10), physical threats and assaults (1, 4, 5, 8, 9), vandalism of property (5, 9), financial exploitation, (3, 5, 10) and in one study, one participant reported sexual exploitation (10).

Location of incidents and relationship to perpetrator

In order to provide more detail on the types of hate crimes, violence or abuse people with mental health problems experience, it is important to describe where the incidents usually took place and the individual's relationship with the perpetrator/s.

Whilst out in their local communities, participants from several studies described how their neighbours, more often teenagers and children, would shout offensive comments and sing abusive chants at them (5, 6, 8, 4). This verbal abuse would usually result in the perpetrators specifically setting out to expose the victim's mental health problems. Some experienced verbal abuse from strangers whilst on public transport (2, 11) whilst in one study, one participant reported physical and verbal abuse by strangers whilst sleeping rough on the streets (10).

Participants in several studies reported experiencing harassment and intimidation from neighbours, landlords and other tenants whilst in their own homes (5, 8, 9, 11). This ranged from children knocking on their door and running away, to various acts of vandalism, such as stones being thrown at windows, graffiti (5) and unwanted content being pushed through their letterbox (i.e. abusive letters, used condoms, pornographic material, lit matches and dog faeces) (9). In Kelly's (Reference Kelly1999) study, one participant reported having their bin emptied out onto their front garden only to then be reported to the local authority with false accusations of not keeping their property tidy. This supports findings by Berzins et al. (Reference Berzins, Petch and Atkinson2003) that there was a significant association between harassment and those living in local authority accommodation for both people living with mental health problems and the general public.

According to Woods & Edwards (Reference Wood and Edwards2005), those with mental health problems are more likely to experience victimisation by people they know as opposed to a student population who are more likely to be victimised by strangers. In some cases, neighbours or other tenants within their supported accommodation would ‘be-friend’ those with mental health problems in order to exploit them, for example, by borrowing money or cigarettes and never paying them back (5, 10). Family abuse was also more likely to be reported by those with mental health problems (Berzins et al. Reference Berzins, Petch and Atkinson2003). This concurs with several of the studies in which participants described how family and friends would also try to take advantage of their disability allowance (7, 9, 10). In one study, participants described how healthcare professionals would keep hold of their money and not give them a choice about how they spent it (3).

In one survey-based study, 38% of respondents reported having been harassed and teased in the workplace by managers, colleagues and the personnel department because of their mental health problems. These findings were supported by Sin et al. (Reference Sin, Hedges, Cook, Mguni and Comber2009) who also reported those with disabilities having experienced victimisation in work and colleges. However, this study did not report details on nature of the victimisation and furthermore, collected data from a non-mental health specific population. Participants in one study reported being victims of crime within psychiatric settings, and in some cases, the offenders were staff (8). Two other studies reported people with mental health problems experiencing victimisation by those in authoritative positions such as health care professionals and police (7, 9); however, there were no details provided on the nature of the offences.

Reasons and motivations for attacks or abuse

There were several motives behind perpetrators’ attacks on those with mental health problems. The most common motivation for the violence or abuse to occur was because of noted differences between the victim and the perpetrator. Examples of this included, the perpetrator holding prejudiced views towards those with mental health problems (4, 8), the victim behaving in ways that may increase the risk that they would be attacked by others (e.g. preaching to others; being confrontational when extremely distressed) (6), and the perpetrator seeing them victim as ‘lesser than them’ (11). Some experienced hostility from individuals who were the same ethnicity and/or had the same faith as them, where those with mental health problems were seen as going against specific identity markers held within that specific community (2). In a 2014 study, some participants described being victimised due to recent focuses on the Government's benefits reform whereby they were called ‘benefit scroungers’ by others (2).

In some studies, participants felt that they had been a victim of a crime because the perpetrator knew they could take advantage of the person because of their mental health problems. For example, some victims believed that they were targeted by family and friends who wanted to take their welfare benefits or medication (1, 3, 5). In one study, participants believed they were an easy target as they would not be believed and would be easily discredited due to having a mental health problem (8).

Some victims felt that teenagers and children who committed hate crimes against them were influenced by the inter-generational beliefs of older family members; they, therefore, modelled the stigmatising attitudes of others (1, 5).

Impact of targeted violence and abuse

Following experiences of hate crime, violence or abuse participants in several studies reported feeling vulnerable, afraid and unsafe about becoming victimised again in the future (1, 2, 9, 3, 12). In contrast, this study found that the general public sample were more likely to experience anger rather than fear (1). In another study, participants who experienced verbal abuse within their local community were more afraid of others finding out about their mental health problems than the actual incident reoccurring (4).

Participants in one study described how their existing mental health problems had either deteriorated or they had developed new mental health problems after being victimised (1). In addition, nearly half of the participant sample reported feeling suicidal (1).

Some studies indicated other impacts of mental health-related targeted violence and abuse. For example, some people experienced financial loss due to exploitation or loss of their job whereas others’ relationships had broken down (8). In one study, participants reported turning to alcohol abuse (2). Individuals also reported physical injuries following from physical abuse (8).

Help-seeking behaviour

People with mental health problems most commonly disclosed their experiences to and sought support from mental health professionals (social workers, nurses and doctors) (2, 7, 10), police (1, 7) or family and friends (7). Other reported sources of support included housing associations, support provider charities (i.e. Victim Support), probation services, solicitors, and local councillors or politicians (2, 8).

According to Pettit et al. (Reference Pettitt, Greenhead, Khalifeh, Drennan, Hart, Hogg and Moran2013), there were a number of factors that helped people to report experiences of what could be categorised as a hate crime. These included a desire to prevent reoccurrence or to protect others, having a good support network, having current or prior contact with services, and a positive therapeutic relationship with mental health or other support professionals. For those who did not want to report hate crime incidents, it helped having someone in an advocacy role who could peruse the matter on behalf of the individual (e.g. someone else alerting the police).

In several of the included studies, the police were a common source of potential help for victims. In Pettit's study (Reference Pettitt, Greenhead, Khalifeh, Drennan, Hart, Hogg and Moran2013), participants described several factors that helped them report crimes and seek help from the police, which included them having a caring attitude, taking the incident seriously, communicating effectively and being willing to liaise with other services or professionals (8). In some studies, participants reported dissatisfaction with previous experiences of reporting incidents that could be classified as hate crimes to the police where they were not taken seriously and/or where reporting had made no difference (8, 1, 5). Participants also described how police had lacked sympathy, were disrespectful, or had not supported the person due to negative attitudes towards mental health problems (2, 8). There were cases where participants described how they had not and would not report incidents to the police due to a fear and distrust of the police, which was often described in the context of previous negative experiences with police (i.e. only had contact when having had police involvement with hospitalisation) (8). In another study, some people did not report to the police as they felt that they ‘would be in the wrong’ (11).

There were also various other reasons why participants chose not to report being victimised because of their mental health problems. Some reported feeling afraid that it would make the situation worse (5, 8), or that they would be penalised (e.g. the support they receive would be negatively affected) (3). In one study, participants reported being worried that access to services would be blocked if they made a complaint about abuse on wards by mental health professionals (8). In some cases, participants were unsure of where to go for support and who to seek help from (8). In another study, a majority of participants (86%) felt solely responsible for keeping themselves safe and therefore did not feel the need to report the incident or seek help from others (7).

Whether people reported the incident or crime was, at times, dependent upon the extent to which the victim understood it to be motivated by their mental health status. For example, in one study, some participants did not perceive the incident to be worth reporting because it was either considered to be a part of everyday life or was not seen as mental health-related disability hate-crime due to the nature of their relationship with the perpetrator (i.e. a member of their family) (11).

Personal coping strategies

Avoidance

There were a number of ways in which people chose to manage and cope with the aftermath of being attacked or abused because of their mental health problem. Participants in several studies most often reported changing their lifestyle in order to avoid similar incidents reoccurring. This ranged from individuals avoiding certain walking routes or places (11), through to avoiding leaving their home altogether (10), with Kelly's study (Reference Kelly1999) reporting one participant having not left their home in 8 months. In more extreme cases, people described having to move homes in order to get away from the verbal abuse and harassment they were exposed to within their neighbourhood (1, 5, 9). As a result of these avoidance strategies, participants often described feelings of isolation and social exclusion (3, 4, 12, 5).

Self-defence

Some individuals preferred to adopt more proactive coping strategies including attempting to reason with their abuser (1). More specifically, Langan & Lindow (Reference Langan and Lindow2004) described incidences where victims attempted to retaliate by returning the verbal abuse, but what was seen as self-defence by the victim was often viewed by others as threatening behaviour due to the person's history of mental health problems (6). One individual described carrying around weapons (i.e. pocket knives and a sock with a rock in it) in preparation for the next time that they are attacked (5).

Acceptance

Linking to those individuals who chose not to report incidences of targeted violence or abuse, some people chose to accept what had happened to them by doing nothing about it (5, 1, 8). Findings from two studies noted that crime victims with mental health problems were less likely to make changes following the incident compared with victims from the general population (1, 8). Furthermore, participants in one study reported ‘doing nothing’ in order to avoid experiencing similar incidences in future (10).

What types of help and support do people need or want?

Reflecting the findings from Mitchell et al. (Reference Mitchell, Baxter and Glendinning2012), only three of the 13 studies included the perspectives of people with mental health problems who had been victims of targeted violence, hostility or hate-crime on what type help and support is needed. This constitutes a gap in the UK literature. In one study, participants were asked what sort of support would they want or need following from their experiences of hate-crime (8). Participants’ suggestions included crime prevention advice, advice on how to access the criminal justice system and psychological support services such as talking therapies. The need for the delivery of psycho-educational classes for the general public to help stop anti-social behaviour and targeted abuse within local communities was highlighted (1). One study showed that people with mental health problems were not routinely involved in discussions about risk management and safeguarding, which was indicated as a problem (6).

Discussion

Much of the current general research on adult safeguarding in the UK explores systemic issues, service configuration and models, decision-making and practitioner concepts of safeguarding (Johnson, Reference Johnson2011; Graham et al. Reference Graham, Norrie, Stevens, Moriarty, Manthorpe and Hussein2014; Norrie et al. Reference Norrie, Stevens, Graham, Hussein, Moriarty and Manthorpe2014; Trainor, Reference Trainor2015). Research suggests that reactive and technical approaches to risk management and safeguarding are inadequate for addressing the complex circumstances and individual needs (Manthorpe et al. Reference Manthorpe, Stevens, Rapaport, Harris, Jacobs, Challis, Netten, Knapp, Wilberforce and Glendinning2008). There is evidence that organisational and professional concerns about risk and safeguarding could impede progressing UK adult safeguarding practice reforms for people with mental health problems (Carr, Reference Carr2011). The risk-averse culture within UK mental health services has been found to be disempowering for service users who are unable to be meaningfully involved in the processes of risk management, assessment and decision-making that affect them (Whitelock, Reference Whitelock2009; Faulkner, Reference Faulkner2012; Wallcraft, Reference Wallcraft2012).

Literature reviews highlight the absence of all service user perspectives, and particularly mental health service user perspectives, in studies on risk and safeguarding and that risk and safety, are defined by practitioners and articulated using managerial language (Mitchell & Glendinning, Reference Mitchell and Glendinning2007; Carr, Reference Carr2011; Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Baxter and Glendinning2012; Wallcraft, Reference Wallcraft2012). Only one piece of UK user-led research work started to address the issue of absent user voices and revealed that fear was a significant concern for service users, particularly those with mental health problems, but this is not necessarily something considered by practitioners (Faulkner, Reference Faulkner2012) or community safety. Discourses from the UK on adult safeguarding and risk, mental health and ‘disability hate crime’ have remained largely separate across research, policy and practice.

Despite limitations on the number of studies, and the types and quality of evidence included in this scoping review, the findings reveal a degree of thematic consistency and important insights into mental health service user experiences of targeted violence and hostility, victimisation or ‘disability hate crime’ and adult safeguarding that begins to address some of the gaps in the knowledge.

The studies provide information on the types of potential hate crime experienced by people with mental health problems, indicate where incidents take place, give some insight into the victims’ relationship with the perpetrators. The small body of research studies examined here gives an overview of the location of incidents as well as the psychological, social, financial and physical impacts on the victim. The included studies also highlighted the types of help-seeking behaviours adopted by the victims; where they seek support and whom they disclose their experience to; the factors that may help or hinder the victim from reporting the crime and/or seeking support through to the types of support that people may want or need. The studies revealed range coping strategies that people with mental health problems adopted in response to experiences of targeted violence or abuse.

From the studies, it appears that people who are targeted for violence and abuse or exploitation because of their mental health status or problems are more likely to have a fear than an angry response, with a tendency to avoid situations perceived to be risky or to self-isolate, and a heightened sense of vulnerability. Some of the reported fear is related to fear of exposure of having mental health problems. This raises a wider concern about factors that prevent the social and community inclusion of people with mental health problems in the UK, and circumstances that increase people's vulnerability. However, the studies raised the question: are people being targeted because someone has an active dislike for them due to their mental health problems OR are they victimised because the perpetrator/s know that someone is vulnerable because of their mental health problems and associated circumstances?

Although none of the studies allowed for a comparator in terms of types of disability, it is notable that people with mental health problems tended to feel that they would not be believed by authorities; that somehow the abuse, violence or exploitation is their fault or is to be accepted as part of daily life; and that some saw themselves as an ‘easy target’ because of their mental health problems. These patterns of ‘psychiatric disqualification’ (where people feel they will be delegitimised or discredited because of their mental health problems: Lindow, Reference Lindow, Newnes, Holmes and Dunn2001), chronically low self-esteem or self-worth can act a serious barriers to victims of mental-health related disability hate crime from recognising abuse, accessing appropriate mental health, police and criminal justice support and from pursuing their right to justice as citizens. Finally, the literature suggests that experiences of violence and abuse relating to mental health can increase the risk of further mental health problems or mental health crisis.

The review revealed some tentative but important findings about the relationship of services and professionals to the issues under investigation. Mental health professionals (including social workers), police or family and friends were most commonly identified as sources of help or the first course for reporting the incident. Adult safeguarding did not feature strongly in the findings about help-seeking behaviour and reporting. Of particular concern was the emerging finding on experiences of mental health-related violence, abuse or victimisation within mental health services and inpatient wards, sometimes by staff. In such cases, victims described being too afraid to report the incident because they believed their mental health support would be compromised or that they would be told they were ‘in the wrong’.

Finally, the included studies outlined the importance of positive therapeutic relationships with mental health professionals; advocacy and liaison or joint working between all involved services; clear communication and caring attitudes from police and mental health professionals; and having the incident taken seriously by the person it is reported to. These offer helpful recommendations for improving mental health and policing practice for victims of mental health-related hate crime, or targeted violence and abuse for the UK and potentially, other countries with similar health and social service policies and infrastructure.

Study limitations

Although findings can potentially inform developments internationally, this study is limited to the UK. A limitation of the included studies is in relation to the adopted recruitment and sampling strategies whereby three studies either used opportunistic sampling whilst a further six studies did not report any details on the sampling strategy and/or no specific detail on participants’ demographics. The four studies that used a strategic or purposive sampling strategy provided limited detail on the criteria used to inform their sampling framework.

It is therefore difficult to know how representative and varied the findings are to the types of targeted violence and abuse experienced by mental health service users and whether the findings capture the varied sources of support that are sought and coping strategies that are adopted. The lack of data detailing ethnicity, sexual orientation, physical disability, gender and gender identity makes it problematic to assess if and how these characteristics intersect in cases of mental health-related violence and hostility.

A number of the studies included in the review explored the experiences of mental health service users alongside those of the general public. One study examined hate crime and victimisation without breaking down the data to reveal specific findings for people with mental health problems, so it was very difficult to discern the extent to which study findings were specifically relevant to the scoping review question and topic.

Conclusion

This scoping review provides a UK-based overview of mental health service user concepts and experiences of mental health-related targeted violence and hostility (‘disability hate crime’), risk, prevention and protection; where victims go for help and approach protection and prevention, including what might prevent them from seeking help; and their experiences of the responses mental health services, the police and other organisations to their reporting incidents of violence or abuse relating to their mental health status.

It reveals some specific issues regarding mental health and disability hate crime, particularly relating to victim fear responses, social isolation, ‘psychiatric disqualification’, acceptance of violence or abuse as part of everyday life, stigma and its relationship to help-seeking and the expectation of ‘not being believed’ or ‘being in the wrong’. This suggests that further investigation into disability hate crime with a specific focus on mental health is required; and one that considers other intersecting forms of targeted violence and abuse (such as sexism, racism or homophobia). It also reveals that incidents can occur within mental health settings, with staff cited as perpetrators.

This is a UK-based overview that offers a useful comparator for researchers, policy makers and practitioners in other countries, particularly nations with social policies on safeguarding vulnerable adults. It is well documented that the stigma, discrimination, and abuse experienced by those with mental health problem are a concern for global mental health, with the action being taken on an international level (Thornicroft et al. Reference Thornicroft, Brohan, Kassam and Lewis-Holmes2008; UN Human Rights Council, 2017). It is likely that there will be commonalities and variations in people's experiences internationally, and comparative national reviews of research are useful for understanding the international picture on the targeted violence and abuse of people with mental health problems and service responses to it.

Acknowledgements

This report is independent research by the National Institute for Health Research School for Social Care Research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR SSCR, NHS, The National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health for England and Wales.

Declaration of Interest

None.