Introduction

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, leisure was still reserved for the few. By the end of the twentieth century, however, most workers had secured access to leisure through a regulated normal working time of around 40 or fewer hours per week, annual paid leave, and compensation for overtime (Rasmussen Reference Rasmussen2016; Rasmussen and Knutsen Reference Rasmussen and Knutsen2022). By all accounts, this common cross-country pattern represents a revolution in the organization of paid work.Footnote 1 At the same time, the speed and extent to which states decided to regulate working time to secure workers' leisure varied between and within countries over time (Messenger et al. Reference Messenger, Lee and McCann2007; Rasmussen Reference Rasmussen2016). In the following, I will review the central literature on this topic, and this paper’s place within it.

Researchers have investigated the effect of s numerous macro-structural factors such as democratization, revolutionary threat, electoral rules, and globalization in the form of trade on working-time reforms. For example, Huberman (Reference Huberman2012) argued that increasing trade dependencies and democratization by the extension of the vote fostered adoption of early factory laws regulating hours for children and women and reduced worked hours in general (see also Burgoon and Raess Reference Burgoon and Raess2009; Huberman Reference Huberman2004). Anderson (Reference Anderson2018) has moved beyond structural factors to study the role of policy entrepreneurs in factory laws for children. Others again highly the role of extra-parliamentary actors, such as Emmenegger (Reference Emmenegger2014) and Metcalf et al. (Reference Metcalf, Hansen and Charlwood2001) studies on the role of trade unions and collective bargaining in shaping working-time reform, while Rasmussen and Knutsen (Reference Rasmussen and Knutsen2022) find that revolutionary threat from unions and worker councils following the Bolshevik revolution made elites regulate hours for workers in general and adopt the eight-hour day.

In contrast, only a handful of studies have investigated the role of political parties in shaping working-time regulation. Furthermore, as I document below, studies focusing on parties are almost exclusively on developments after the 1960s, long after the initial working-time reforms had been undertaken (Messenger et al., Reference Messenger, Lee and McCann2007; Rasmussen, Reference Rasmussen2016). Additionally, these studies use empirical measures that are only indirectly linked to working-time reforms. This means that we don’t know what role, if any, political parties played in the origins of leisure-securing working-time reforms. Consequently, it is important to inquire which political parties have generally promoted policies aimed at increasing leisure time through reducing working hours, and which parties have resisted such policies.

Initially, studies of partisan effects on working-time reforms have tended to adopt a left-versus-right perspective. A prominent example is Alesina et al. (Reference Alesina, Glaeser and Sacerdote2005), who analyzed actual worked hours from 1960 to 2000 and found that left-leaning parties tend to reduce worked hours more than right-leaning parties.Footnote 2 In their seminal study, Burgoon and Baxandall (Reference Burgoon and Baxandall2004) adopted a more nuanced perspective in terms of differentiating between parties within the party blocks. They argued that countries dominated by social democrats, Christian Democrats, or Liberals develop different “worlds of working time,” with Christian Democrats and social democrats promoting fewer working hours than Liberals overall. Christian Democrats played a decisive role in promoting a system characterized as “welfare without work,” which in terms of working-time reductions involved giving tax breaks to employers that gave working-time reductions to their employees. However, Burgoon and Baxandall’s (2004) study did not measure the emergence of working-time regulation per se but actual worked hours between 1979-2000.

The studies by Alesina et al. (Reference Alesina, Glaeser and Sacerdote2005) and Burgoon and Baxandall (Reference Burgoon and Baxandall2004) both use actual worked hours and exclude the initial major working-time reforms. However, changes in actual worked hours are influenced by various factors, including other state policies such as pensions and labor market factors, and changes in worked hours may not be directly related to working-time reforms. Additionally, initial country rankings in working time have remained relatively stable over time, indicating the importance of historical forces during the origins of working-time regulation (Huberman and Minns, Reference Huberman and Minns2007). As a result, there is a need to reexamine the theoretical foundations of party preferences for working-time reforms and to conduct empirical tests using more detailed historical data on the emergence of working-time reforms.

The perspective outlined here argues that parties’ preferences for working-time reform are driven mainly by class and rural/urban differences in parties’ constituencies. Class is here used in highly aggregated terms, as individuals sharing a similar situation in labor-market terms; that is, the class of employers versus the class of employees (workers; Korpi Reference Korpi2006: 173). In essence, I argue that employees will have an interest in regulating hours while this is opposed by employers. Working-time politics cannot, however, be reduced to class alone. While Burgoon and Baxandall (Reference Burgoon and Baxandall2004) incorporated class and religion into their three-world framework, they overlooked the role of rural/urban differences, which Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) originally highlighted.

Given their strong position within liberal and conservative parties worldwide as an interest group and voter block, farmers composed a decisive veto force on both major parties’ policy positions (Rokkan Reference Rokkan1987: 152). Farmers also formed their own parties, making them an important coalition partner in European countries during the 1920s and 1930s (ibid.: 325–28). It follows that partisan theory of early working-time politics should consider farmers’ preferences to accurately portray why political parties are for or against working-time regulation. Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) defined the interest of farmers according to the work of Baldwin (Reference Baldwin1990) and Manow (Reference Manow2009). Baldwin (Reference Baldwin1990) claimed that farmers and their parties were central in ensuring the adoption of universal social measures because farmers demanded coverage for the rural sector. Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) amended Baldwin’s (1990) argument into a coalition logic-argument, with farmer parties trading preferred agricultural policy for welfare measures, rather than claiming that farmers would advocate welfare measures as such. This idea of farmers being interested in the extension of welfare benefits has been challenged by Bengtsson (Reference Bengtsson2019) and Rasmussen (Reference Rasmussen2022), both of whom argued that farmers as a party and interest groups outright opposed or only hesitantly accepted welfare measures.

The aim of this paper is to make a contribution to the working-time literature by investigating how working-time policy emerges from party politics shaped by class and sectoral differences. In so doing, I examine the role of trade unions, employers, farmers, and party families in developing working-time regulation with parliamentary appeals and vote data (roll-call votes; RCV). I compiled all RCVs available on issues of working-time regulations in Norway – in total, 65 RCVs totaling 4,194 votes by members of parliament (MPs). These data include fundamental aspects of working-time regulation, such as votes for introducing and lowering the normal workweek, extensions to other sectors, and limits to overtime. The given aim of the chosen RCVs was to standardize work conditions and increase leisure by restricting employers’ ability to utilize labor. Additional evidence comes from a qualitative analysis of four reform attempts with over three hundred individual legislative appeals from unions and employers, and reform data on 32 industrializing countries between 1848 and 2010. The individual legislative appeals allow for precise analysis of union and employer preferences, and although not perfect, the country-level data afford a greater ability to generalize findings. Together, the various data types allow more thorough testing of the various parts of the theoretical framework than would be possible with a single data type independently.

In the following, I first present the theoretical framework to understand the politics of working-time regulations; second, I contextualize the Norwegian case used to test this framework; third, I outline the research design and summarize the qualitative and quantitative evidence for or against the presented framework; and fourth, the final section concludes and suggests future avenues for research on working-time regulation.

The politics of working time

Müller and Strøm (Reference Müller and Strøm1999) conceptualized parties as both office- and vote-seeking. In other words, parties have historical and ideological ties to core constituencies; to gain power, however, they also must adjust their policies to attract voters. A core constituency means voters as well as organized interests, such as unions and business organizations, with strong interlinkages. Because parties can have core constituencies with preferences that diverge from those of the median voter, parties end up in a dilemma: Pursuing their core could lose median voters. To solve this dilemma, parties search for bridge policies that both their core constituency and the median voter prefer (De Sio and Weber Reference De Sio and Weber2014: 871). Here, I argue that working-time regulation was a bridge policy for parties with weak to no ties to employers or self-employed farmers but strong ties to workers, such as social democrats, social liberals, and urban liberals, but not conservatives, farmers, or rural liberals. In essence, the politics of working time becomes structured along class and sector (urban/rural differences).

Throughout the twentieth century, a primary concern of organized labor was securing the right to leisure (Cross Reference Cross1985; Huberman and Lewchuk Reference Huberman and Lewchuk2003). In tandem with unions, left parties worked to solve collective-action problems for low-wage workers who could not set their preferred hours by bargaining with employers, pressing for collective bargaining arrangements, or national legislation (Alesina et al. Reference Alesina, Glaeser and Sacerdote2005; Metcalf et al. Reference Metcalf, Hansen and Charlwood2001). Given the low incomes, especially of unskilled laborers, unions demanded increases in wages to offset hour reductions in these bargains. Therefore, working-time reductions could secure leisure and result in hourly wage gains. For example, introducing the eight-hour day in Sweden resulted in the most rapid wage increase in its history (Bengtsson and Molinder Reference Bengtsson and Molinder2017). Unions would also pursue hour reductions to combat unemployment because employers would hire more staff to keep production constant. Workers and their unions had several interlinked reasons for supporting working-time reforms.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Trade unions should support working-time regulations

Socialist parties’ core groups of working-class workers and their unions would nowhere afford the socialists an electoral majority. Any successful electoral strategy aimed at the electoral majority would require overtures to the middle classes. This needs to attract higher-income-strata-occupied socialist theoreticians since the first major socialist parties (e.g., Berman Reference Berman2006). The stage was set for the dilemma of electoral socialism that Przeworski and Sprague (Reference Przeworski and Sprague1986) conceptualized. In the electoral dilemma, socialists face a trade-off: They can achieve an electoral majority only by appealing beyond the working class, but attracting middle-class voters could dilute the working-class message and thus reduce the worker vote.

Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1985) criticized the electoral dilemma on theoretical grounds; others argued that unionization could effectively mitigate it (Rennwald and Pontusson Reference Rennwald and Pontusson2020). However, it is my opinion that the need to apply to the middle classes for electoral success is a powerful predictor of why most successful social democratic parties left behind class-anchored goals such as the socialization of property. It is also congruent with the conceptualization of parties as both office- and vote seeking, as outlined previously. On this theoretical basis, the question is whether working time is an issue that entailed an electoral trade-off for the socialists.

I argue that this trade-off between middle-class and worker-class preferences did not rise to the same extent for working-time regulation. Because the demand for leisure tends to increase with income (Huberman and Minns Reference Huberman and Minns2007: 540; Owen Reference Owen1971; Wilensky Reference Wilensky1961), I argue that middle-income voters, such as commercial employees, would end up supporting lower-income-workers’ demands for fewer hours. The logic presumes that middle-class voters valued reduced hours because their income level was such that a marginal unit of salary was worth less than a marginal unit of leisure time. By extension, working-class voters wanted working-time regulations. Because they had high work hours and low absolute levels of leisure time, they would receive higher marginal utility from the reduced work hours. This should be especially true in occupations with low autonomy: workers with standardized work schedules are unable to influence the content and structure of their work. Even if higher-income voters could bargain with employers for lower hours, regulations helped salaried employees solve the coordination problems that arose because leisure was enjoyed more when shared with others. Employees had an interest in arrangements that facilitated such coordination (see Alesina et al. Reference Alesina, Glaeser and Sacerdote2005).Footnote 3

I stipulate that since middle- and low-income workers both preferred fewer working hours, social democratic parties could promote regulation to reduce work hours and thus make overtures to urban middle-class voters without losing their working-class base.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Representatives from socialist parties should support working-time regulationFootnote 4

Second, parties whose primary support came from the middle classes could use working time to build a worker–middle-class coalition (Hicks et al. Reference Hicks, Misra and Ng1995; Luebbert Reference Luebbert1991; Rokkan Reference Rokkan1987: 146–52). Working-time regulation could overcome the problem facing liberal parties at the end of the nineteenth century – the flight of worker voters and trade unions to social democratic parties (Hicks et al. Reference Hicks, Misra and Ng1995: 330). Only by bridging this gap and appealing to both middle- and lower-income urban workers could the liberals slow the social democrats’ growth (Luebbert Reference Luebbert1991: 62–98). As socialists faced the dilemma inherent in winning over the middle classes, the Liberals also faced a dilemma of winning the worker vote without losing the middle class. Diluting their middle-class message by promising extensive redistribution might see them lose their core middle-class supporters. Although work-hour regulations would entail limiting the earning distribution of the employees (Huberman 2012), these could be offset by increased leisure. Consequently, working-time regulation is preferable in bridging a worker–middle-class alliance for liberal parties.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Representatives from liberal parties should be as likely as Socialists to support working-time regulation

Parties representing producers’ and employers’ core-constituency groups are expected to resist working-time reductions. Why? The answer is twofold. First and foremost, regulating working hours challenges employers’ managerial rights, with the state encroaching and limiting production and lowering firms’ flexibility in changing market conditions (Compston Reference Compston, Ebbinghaus and Manow2001: 131–32). Second, regulations would increase labor demand, impacting urban and rural employers differently. With hours fixed per employee, firms would need to hire new workers or invest in machines (which require capital and further risk-taking) to keep production constant. The fixed costs per worker would increase employers’ expenses, even for firms that hired only for seasonal work. Search costs were especially high for employers that depended on skilled workers, increasing the likelihood of poaching or international labor search. I argue that in a context in which regulations have yet to be introduced, these concerns overrule the possible benefits of regulation to employers, such as increasing entry costs for new competitive firms (Swenson Reference Swenson2002).Footnote 5 Conservative parties, which tend to build their core constituency among employer groups, therefore should oppose working-time regulations.

Hypothesis 4(H4): Employers in general should oppose working-time reforms.

Hypothesis 5(H5): Compared to Socialists, Conservative parties’ representatives should be less likely to support working-time regulations.

I argue that farmers, as producers and employers, would operate under a logic similar to urban employers in a context of increasing marketization of agriculture and integration in the world market. The rapid integration of wheat markets after 1870 left producers at a disadvantage as wheat prices plummeted (Friedmann Reference Friedmann1978). This meant that farmers would come to view the question of working-time regulation first as a managerial and cost issue and second as a question of uniformity: Farmers claimed that rural work conditions required more flexibility than factory work, meaning attempts to regulate hours would make farmers unable to respond to the changing seasonal conditions inherent in farming (see Section 4.3). Therefore, I argue that farmers should pursue a strategy of coverage restrictions – limiting regulations in industrial establishments.

Although farmers could opt to restrict the application of laws to industry, this strategy incompletely protected farmers’ interests; as Lewis (Reference Lewis1954) pointed out, economic development ends the state of an “unlimited supply of labor in the countryside.” This had a profound impact on rural producers. As underemployed and underpaid labor migrated to urban factories (Alvarez-Cuadrado and Poschke Reference Alvarez-Cuadrado and Poschke2011: 128), farmers had fewer peasants to hire; their labor costs increased, while their potential influence over the workers declined (Ardanaz and Mares Reference Ardanaz and Mares2014; Rasmussen Reference Rasmussen2022). Lewis (Reference Lewis1954) and Harris and Todarro (Reference Harris and Todaro1970) highlighted how the urban “pull factor” was higher urban manufacturing wages (see summary of the literature on urban pull factors and empirical test in Alvarez-Cuadrado and Poschke Reference Alvarez-Cuadrado and Poschke2011). Although wages were undoubtedly important, my opinion is that the wage view underplays differences in risk factors between sectors. The risk for accidents in factory work was decisively higher than in agricultural work, meaning migrating workers gambled with health and safety for higher wages (Ot. prp. 35 1914). This meant that policies that moderated the risk of accidents in factory work could also potentially increase urban migration.

Adopting this rural-urban flight framework makes clear why even laws restricted to factories threatened to increase rural–urban mobility. Factory acts aimed to reduce the harsh working conditions urban workers faced, with reformers highlighting long work hours as a primary driver of work accidents (Ot. prp. 35 1914: 35–54). If successful, factory acts could fuel migration from rural centers into the urban economy, increasing farmers’ labor costs or decreasing their production if they could not increase wages. Whether factory acts successfully drove down accidents is not the decisive point; as I will show presently by reference to the discussions in the Norwegian Storting (Section 4.3), farmers here believed they would be successful. Urban employers’ new demand for workers reinforced this trend: Reduced hours would force new hires and increase wages, resulting in increased rural flight. The second point is that farmers tend to resist working-time reductions to reduce urban migration and secure high rural-labor supply.

Hypothesis 6(H6): Compared to Socialists, farmer parties’ representatives should be less likely to support working-time regulations.

Farmers’ position on working-time regulation had consequences for other parties. Although sometimes urban, Liberal parties could also encompass rural interests, especially farmers with some degree of capital and employer responsibilities (e.g., family farmers; Luebbert Reference Luebbert1991). I argue that Liberals with rural constituencies had to play a complicated game of ensuring that new regulations did not benefit urban interests at a cost to the rural areas or threaten the role of (rural) employers (Rokkan Reference Rokkan1987: 146–47, 152). This meant that liberal parties should be divided on the issue of working time, with agrarian representatives more against regulations and urban representatives more in favor. I, therefore, present a new hypothesis concerning the Liberals’ intraparty differences.

Hypothesis 7(H7): Urban Liberal representatives should be more likely than rural Liberal representatives to support working-time regulations.

In contrast to the Liberals, the urban–rural split was not present for social liberals, who instead aimed to mobilize urban and rural wageworkers (Aasland Reference Aasland1961: 18–21). This meant social liberals had no incentive to moderate their social-policy stance as the Liberals did. Instead, I would expect that they should pursue working time as an effective bridge policy for urban and rural segments of their potential voter groups.

Hypothesis 8(H8): Representatives from social liberal parties should be as likely as Socialists to vote in favor of working-time regulation.

Although the existing literature, in my opinion, tends to overlook the Liberals’ or farmers’ role, extensive research was conducted on the impact of Christian democratic parties on the welfare state (Kersbergen and Manow Reference Kersbergen and Manow2009). In a seminal study on actual working time, Burgoon and Baxandall (Reference Burgoon and Baxandall2004) argued that Christian Democrats are the greatest champions of working-time reductions: Fearing that work can crowd out family, charity, church, community, or spiritual pursuits, Christian Democrats support work-reduction policies. Burgoon and Baxandall supported this claim with pooled time-series regressions of Christian Democratic parties in a sample of 18 countries between 1979 and 2000, finding that Christian Democrats reduced the number of worked hours per worker. The link between religion and leisure is far from unproblematic. Classical observers such as Weber (Reference Weber2002) linked Protestantism with work culture. Religious parties also tended to be organized on conservative platforms of parties that have inherently resisted state regulation. Kersbergen and Manow (Reference Kersbergen and Manow2009) reasoned that religious parties constitute cross-class parties pursuing bridge policies that fit such coalitions, and specific welfare policies fit this bill. I could generalize their argument to apply also to working-time regulations. However, it is unclear whether the core religious voter is pro-working-time regulation, reducing working time’s potential as a bridge policy. With the presented corollaries in mind, I suggest a final hypothesis.

Hypothesis 9(H9): Representatives from religious parties should be less likely than socialists to support working-time regulations.

The Norwegian Case

The hypothesis formulated in the previous section will be primarily tested using data from Norway between 1880 and 1940. Norway is a fitting test case for several reasons. First, the party system consisted of conservative, liberal, social liberal, religious, farmer, and socialist parties.Footnote 6 This allows one to test the proposed hypothesis in a specific setting while holding factors such as national culture constant, which could be related to party preferences and working-time regulation.

Furthermore, in line with the scope of the theoretical argument presented above, parties developed linkages and informally coordinated with interest organizations over time but with decisive differences. From its inception, labor had close linkages with the main trade union federation (AFL), with a high personnel overlap and dual membership. The Conservatives developed especially strong linages with the leading business organization, the Norwegian employer federation (NAF). The Liberals lacked any strong linkages to either labor or employer organizations, with the previous worker societies supporting the Social Liberals in the early 1900s (Allern Reference Allern2010). What this means is that Norway falls within the theoretical scope of the party-specific hypothesis formulated in the previous section (in which parties are argued to have linkages to labor market organizations) and, subsequently, is a fitting test case.

Data availability on party and interest organizations' preferences makes Norway an ideal test case. The Norwegian parliament set a low bar for the initiation of RCV, requiring only a single MP to request one.Footnote 7 This means that a host of reform options were roll-called, allowing the establishment of partisan preferences for general working-hour reductions. For example, although the Factory Act of 1915 would introduce a 10-hour workday, the government’s initial proposal was nine hours, and the socialists raised the issue of the eight-hour workday during the parliamentary debate. As a result, between 1880 and 1940 (the period of this study), 65 RCVs were called on working-time issues. In addition, appeals by employers and unions to shift MPs and party policy positions were recorded and published. Combined with its high use of RCV and the presence of various party families, Norway provides an excellent testing ground for the role of parties in setting up working-time regulation while holding several factors constant.

How generalizable are findings derived from Norwegian RCV data? It is important to recognize that Norway is far from unique in its institutional makeup or labor strength between 1880 and 1940. The corporatist system – where peak associations of workers and employers are involved in national economic and social policymaking – had not yet been established (Western Reference Western1991). Union density fell below the average of industrialized countries, with remarkably high levels of industrial conflict coupled with decentralized firms and some branch-level bargaining (Crouch Reference Crouch1993: 82, 86, 123, 137; Rasmussen and Pontusson Reference Rasmussen and Pontusson2018). Although the signing of the Basic Agreement in 1935 signaled the end of the prevalent conflicts, bargaining still took place at the branch level and was not nationalized until the 1950s (ibid.: 206–7). Interest organizations were not yet included directly in policymaking to the extent during the post-war years. Instead, interest organizations still worked to lobby parties, individual MPs, commissions, and parliament during the latter part of the legislative process instead of being included in the initial policy-development stages (see Allern Reference Allern2010). Consequently and in contrast to post-1945 Norway, with its strong neocorporatist institutions, dominating Socialist party, and strong labor movement, the years 1880 to 1940 marked a period of a splintered socialist block and comparatively weak trade union movement.Footnote 8 Therefore, a Norwegian case study of this period, in my opinion, is likely to shed light on the politics of working time in countries without a dominating left party and weak-to-intermediate levels of union organization.

Research design, measurement, and results

I undertook several tests using different data and approaches to test my hypotheses empirically. First, I used an extensive dataset on parliamentary voting records. Second, I evaluated the likelihood of parties making a legislative proposal to reduce hours. Third, I provided qualitative evidence on actors’ preferences and parties’ and interest groups’ motives, focusing on two significant attempts to regulate hours before the adoption of proportional representation (1919) and the formation of a Worker–Farmer coalition in 1935.Footnote 9 I expand on the benefit of including these qualitative mechanism studies next. Finally, I gauged external validity using original data collected on the normal regulated work hours for 33 countries. These cross-country data are somewhat coarser, without distinction between party families as in the parliamentary data, given the lack of cross-national political parties’ data before the 1960s. Space constraints allowed me to focus only on the parliamentary-voting and qualitative parts, leaving out a deeper discussion of the cross-country findings beyond a short summary.

In the analysis of the parliamentary voting, the dependent variable was whether an MP for a specific RCV favored a proposal whose explicit aim was to reduce working time. This variable would take the value 1 if an MP voted against a proposal to reduce hours and 0 otherwise. I undertook two separate analyses using different samples of RCV to capture only RCV reductions for normal working hours and one analysis to encompass all working-time RCV. The latter included votes on issues such as working hours for children or youth, special limits for women, overtime limits and remuneration, coverage of various sectors, and hours in public industry, to capture the wider picture of reduction of working time. This former sample is included because it is closer to the theoretical discussion, focusing on standardization of working conditions and hour reductions. To provide some context on why these votes were undertaken, a short description of Norwegian working-time reforms is provided in Appendix (D).

To capture the effects of parties on MPs' voting, I classified all MPs’ party affiliations based on the election records. I grouped the parties according to their ideological profile: The dummy, Socialist, indicates the Social Democrats, Norwegian Worker Party, and Communist Party. Norway had three major conservative parties: the Conservatives (1884–), Coalition Party (1903–1909), and Free-Minded Liberal Party (1909–). The dummy, Conservative, indicates all three. Norway also had two parties organized around religious issues: the Christian Democrats (1933–) and Moderate Liberals (1888–1906), indicated by the dummy, Christian Democrat. Norway also had one Liberal (1884–) and one Social Liberal (1903–1940) party, indicated by Liberal and Social Liberal, respectively. Finally, the dummy, Farmer, indicates the Farmer Party (1919/1921–).

To control for local demand and individual motivation factors, which also may correlate with MP party affiliation and support for working-time reforms, I included a set of conservative controls (i.e., variables that are highly correlated with MPs voting and party membership). First were occupational dummies using the Norwegian Center for Research (2020) politician database’s fine-masked occupational scheme (38 categories). Second was a set of RCV dummies (RCV-1). For each RCV, I held constant factors such as who proposed the vote, which government was in power, and changes in electoral support. This is a highly conservative control. Third, I included dummies for the representative’s electoral district (Dist-1), allowing separation of demand factors unique to an election district. I clustered standard errors by MP.Footnote 10

To ensure that a specific combination of variables did not determine the results, I first ran a set of sparse models with only the primary explanatory factors. I then sequentially built the models, with each subsequent model including the controls from the previous models. At its most conservative, I estimated the following linear probability modelFootnote 11 :

Here the probability of voting against the generous option (Vote) for an MP (i) for a specific roll call (t) is a result of the independent variable of interest (Party), occupational dummies (Occupation), roll-call dummies (RCV), and dummies for election district (District).

Roll-call votes results

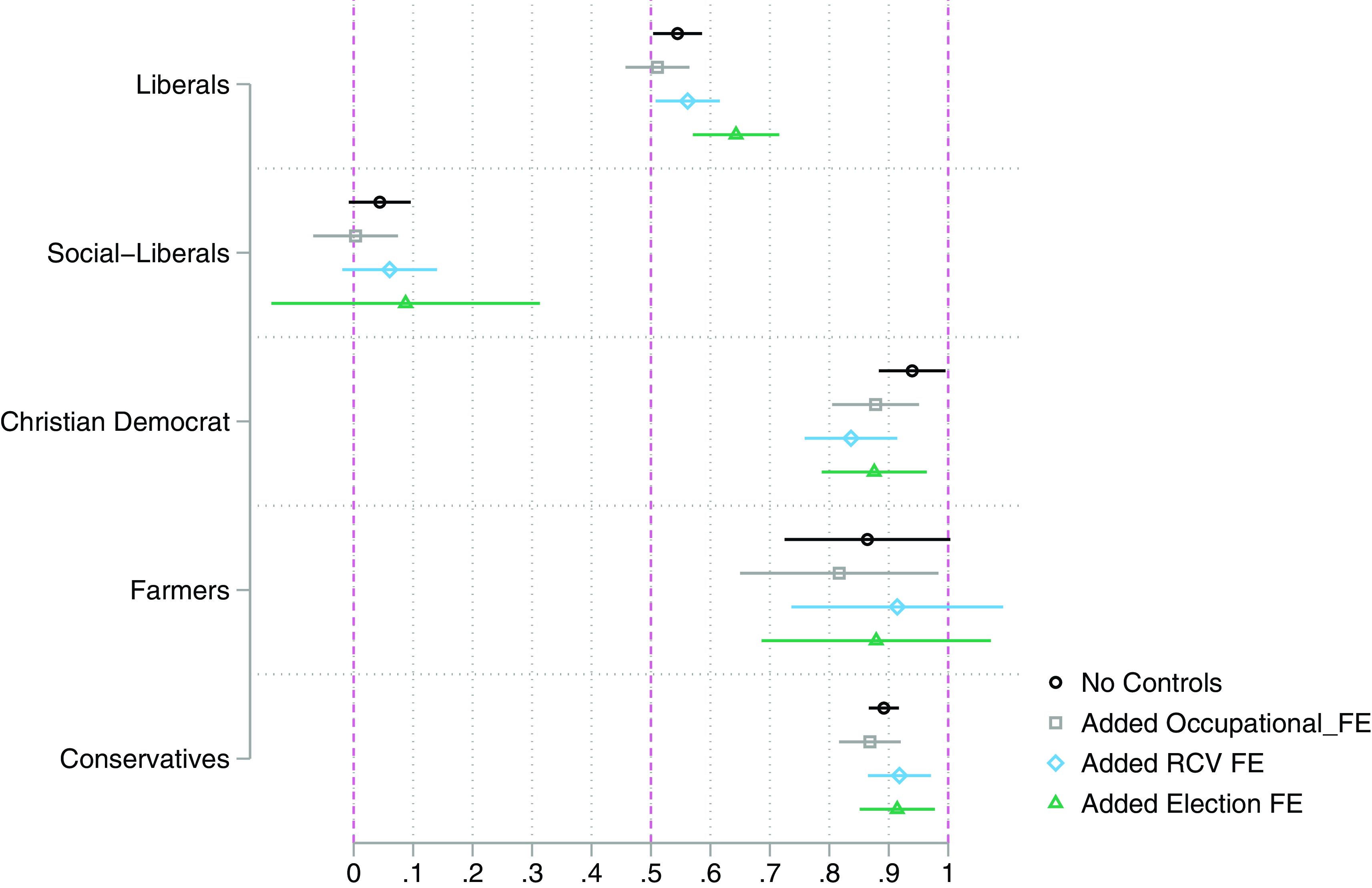

Figure 1 shows the results from a series of models on the probability of voting against a generous working-time reform, by party compared to a socialist MP. The first model includes only party membership as a predictor. I then added occupational fixed effects, controlling for differences in MPs’ occupational backgrounds and next, RCV fixed effects, controlling for unique factors of each RCV. The last model included election-district fixed effects, controlling for unique local-demand effects. The estimated coefficient’s confidence interval overlapped the various model specifications, illustrating that the estimated coefficients were stable to alternative model specifications, even quite conservative controls.

Figure 1. Differences in Predicted Probabilities of Voting Against Working-Time Reforms by MPs’ Party Compared to Socialist MPs. Note. Results from a series of linear probability models with standard errors clustered by person for 65 roll call votes between 1880 and 1940 (tabular presentation in Appendix A). All models are nested, with subsequent models including the above specifications. FE indicates fixed effects. The horizontal 0.5 line indicates the position of parties equally likely to vote against or for.

To ease interpretation, Table 1 gives a summary of the hypothesis and associated findings. As shown, the trade union and employer hypothesis (H1 and H4) can only be tested using the qualitative data. I therefore only refer to H1 and H4 in the qualitative section.

Table 1. Hypothesis and findings from the specific tests

Note: “.” signifies that I cannot directly test this hypothesis in this specific test. Not robust signifies that I find some evidence supporting the hypothesis, but that the result is sensitive to modeling choices.

The results revealed clear and significant party differences. The MPs from all major parties except Social Liberals were significantly more likely than the socialists to vote against a proposal reducing working hours, supporting H2 (which predicts this outcome for the Social Liberals). Liberals were significantly and substantially less likely than socialist MPs to vote for hour reductions – around 50 percent less likely. The final model, which included fixed effects for election districts, increased that difference for the socialists to 60 percentage points. As shown next, this was because urban representatives voted more in line with Social Liberals, whereas representatives from rural districts voted more as Conservatives. In sum, Liberals were clearly different from conservatives, being 30 percent to 40 percent more likely to vote in favor of a working-time reform. That is, one cannot subsume Liberals or Socialists within conservative politics, meaning these results go against H3, which stipulates that representatives from liberal parties should be as likely as Socialists to support working-time regulation. Instead. Liberals take an intermediary role compared to Socialists and Conservatives.

In line with H5, stipulating that the Conservatives should vote for working-time reforms less often than the Socialists, and H6, stipulating that Farmers should vote for working-time reforms less often than the Socialists, Farmers, and Conservatives were 80 percent to 90 percent less likely than Socialists to vote in favor of a working-time reform. Further, H7 requires some additional modifications and is therefore tested separately. In line with H8, which stipulates that representatives from Social Liberal parties should be as likely as Socialists to vote in favor of working-time regulation, Social Liberals are predicted to only diverge from socialists by 4 percentage points, with the confidence interval from 0 to 0.10, indicating a fairly precise estimate. This goes a long way in indicating that political mobilization around a Social Liberal ideology would have resulted in similar working-time reductions as under a social democracy.

In contrast to the claims of previous research but in line with H9, which stipulates that representatives from religious parties should be less likely than socialists to support working-time regulations, I did not find that religious parties in Norway voted for working-time reductions; rather, quite the opposite. The MPs from religious parties voted as conservatives, being 90 percentage points less likely than a socialist to vote in favor of a proposal that would reduce hours. This pattern held even when splitting the party categorization by estimating separate coefficients for the Christian Democrats and Moderate Left. Results were robust to alternative estimation procedures, such as hierarchical logit models, simple logit models, or estimating with a Tobit link function instead of the logit.

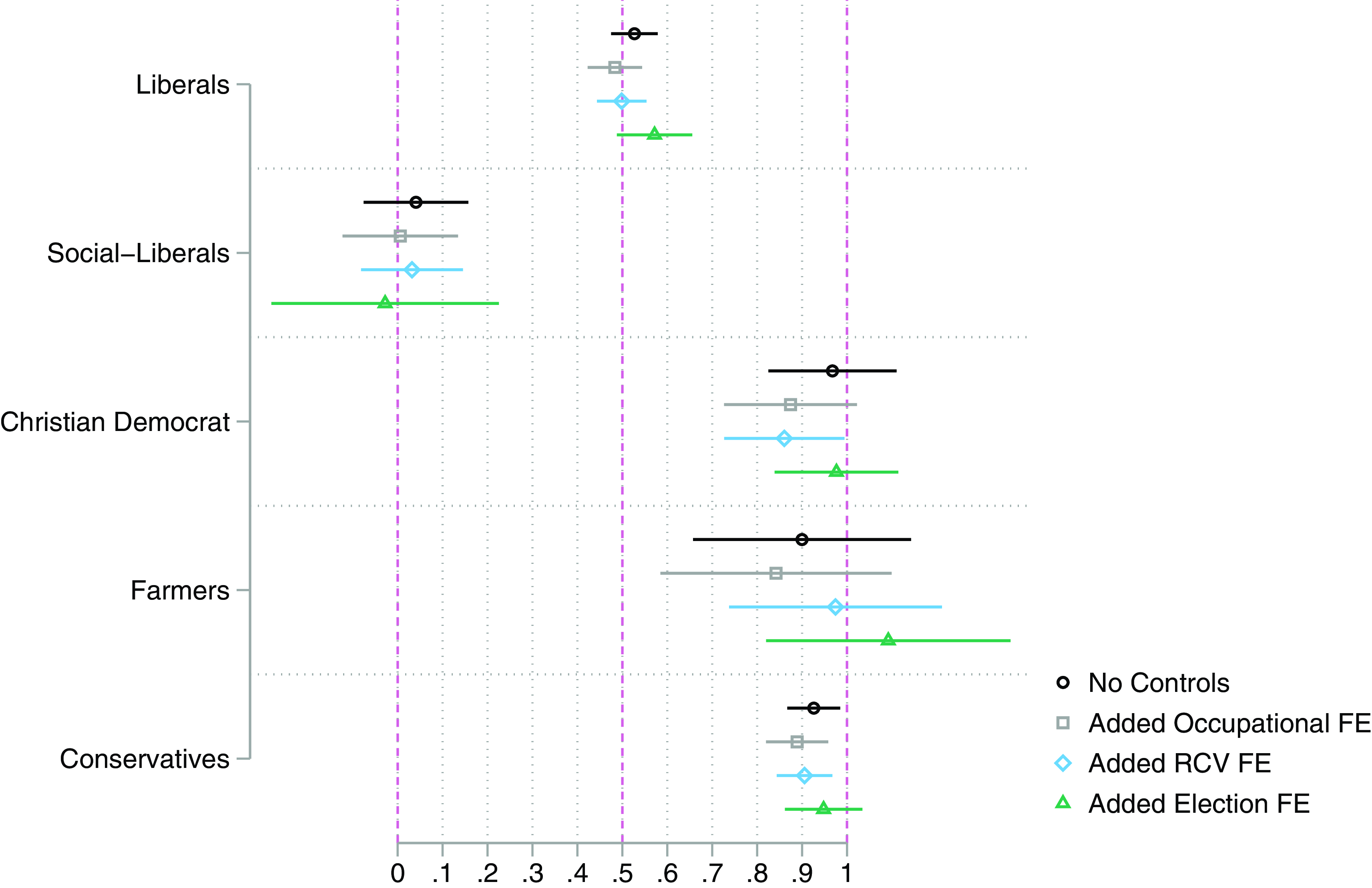

Until now, I included RCV on various aspects of working-time regulation (nightwork, child hours, etc.). However, some votes were more important than others in setting hours, and the theoretical discussion has been concerned more with the general reduction of hours than gender, youth-specific reductions, or nighttime work constraints. Therefore, Figure 2 shows the sample restricted to votes concerned only with reducing normal working hours (22 RCV; 1,564 observations). In line with H2, Socialists voted in favor of hour reductions in almost all instances, with a 2 percent predicted probability of voting against them. Against H3, I did not find that Liberals voted in tandem with socialists, being about 60 percentage points less likely to vote in favor. Conservatives, Farmers, and Christian Democrats, on the other hand, were predicted to vote against hour reductions in almost all instances compared to the socialists. Therefore, results for votes on “reducing normal working hours” are in line with results for all working-time regulation votes, showing clear party differences that, in general, fall in line with expectations.Footnote 12

Figure 2. Differences in Predicted Probabilities of Voting Against Proposals to Reduce Hours by MPs’ Party Compared to Socialist MPs. Note. Results from a series of linear probability models with standard errors clustered by person for 22 RCV between 1880 and 1940 (tabular presentation in Appendix A). All models are nested, with subsequent models including the above specifications. Results are substantially similar when estimating with logit or tobit regression. FE indicates fixed effects. The horizontal 0.5 line indicates the position of parties equally likely to vote against or for.

The last section of the RCV results focuses on H7, which stipulates that urban Liberal representatives should be more likely than rural Liberal representatives to support working-time regulations, testing in two ways whether agrarian-supported Liberals differed from urban-supported MPs in their support for working-time reforms. First, I separated Liberals who conducted their economic activity in rural-versus-urban election districts. Second, I used election statistics to ascertain whether the Agrarian Society (Landmandsforbundet), the interest organization that later would establish the Farmer Party, supported a Liberal candidate. The results indicated that urban representatives voted more as Social Liberals, and rural representatives as Conservatives or Farmers (Supplementary Figures B1 and B2). A city MP was 10 to 20 percentage points more likely to vote in favor of a generous proposal. In contrast, an Agrarian Society-supported MP was 10 to 20 percentage points less likely to vote in favor of one. However, the results were sensitive to controlling for each unique RCV factor, especially Agrarian Society support. With these caveats in mind, the source of splits within the Liberal Party on working time appears agrarian in origin, supporting the hypothesis that Urban Liberal representatives should be more likely than rural Liberal representatives to support working-time regulations.

Legislative proposals

I have established that parties differed in their voting for or against working-time reforms fell in line with expectations, but I do not know whether the same parties that voted for reform were also likely to push the issue onto the legislative agenda; that is, whether they were likely to act as agenda-setters. In this section, I test the latter systematically by investigating whether party membership predicts the likelihood of making a legislative proposal to reduce working hours. Appendix B shows the percentage of proposals for or against the status quo (no change vs. hour reduction) in percentages by party origin of the proposal. In line with H2, Socialist MPs made proposals only to decrease working hours. Against the expectation that Liberals would be as likely as socialists to propose working-time reforms (H3) but in line with expectations for an internally split Liberal Party (H7), the Liberals were equally likely to propose reducing hours as maintaining the status quo. Close to all Conservative proposals were against hour decreases, either keeping the status quo or proposing smaller changes than the alternative, supporting H5. Similarly, Farmers made only proposals that would increase hours (or maintain the status quo) in line with H6. Social Liberals were again as likely as socialists to propose hour reductions, supporting H8. Finally, Christian Democrats made only proposals that would increase hours (or maintain the status quo), in line with H9. Results show that parties that voted in favor of working-time reforms also were those parties likely to push working-time reforms on the agenda.

Qualitative evidence on actors’ Preferences and Parties’ and Interest Groups’ motives

Oral statements in parliament and hearing statements regarding Factory Acts of 1909 and 1915

In this section, I analyze statements made by parliamentarians and interest group representatives regarding two attempts to regulate working hours that took place prior to the adoption of the eight-hour day. The first of these is the revision of the Factory Act in 1909 and then the second revision of that act in 1915. In referring to direct quotations of speeches made in parliament and hearings in response to legislative proposals, I attempt to discern the parliamentarians’ and interest group organizations’ opinions on working-time extensions and whether these align with my hypothesis outlined in Section 2. This section allows testing of H1 concerning trade unions' support for working-time reforms and H4 on employers’ opposition to the same reforms. In addition, if previous results on party preferences find support using more qualitative evidence, the credibility of the finding increases (Seawright and Gerring Reference Seawright and Gerring2008). Qualitative evidence can also be used to test the specific mechanism in a theoretical argument by confirming that part of the causal pathway in an argument is actually present (Gerring Reference Gerring2006). For example, Conservatives should oppose working-time reforms by referencing their consequences for employers, farmer interests oppose it based on fears of rural depopulation, and we should find evidence of these interest groups influencing party positions.

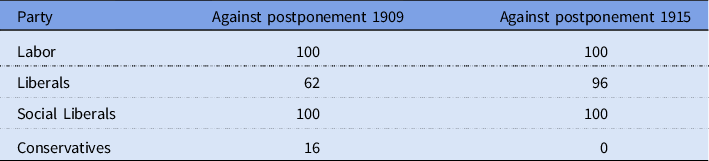

First, to summarize the background for the proposals: In 1908, after years of internal debate, the parliamentary social commission split in their treatment of a factory act revision. The conservative government had put forward a proposal without regulation of hours, and the social commission split regarding whether to amend the government proposal. The majority position (Social Liberals, Socialists, Liberals) proposed extending coverage to various infrastructure and craft firms and introducing a normal workday, maximal working time (72 hours), and overtime remuneration. The minority position (Conservatives) opposed these changes. The proposal came to parliament only to face farmer and Liberal candidate Langeland’s postponement proposal (Stortingstidende 1908: 964). The postponement proposal won out against 22 votes (not roll-called). In 1909, the original government proposal was brought again to the social commission with the same outcome. Langeland again proposed postponement but lost the majority this time. Table 2 reveals apparent party differences: Socialists and Social Liberals, together with a majority of Liberals present, all voted against, and Conservatives in favor of postponement.

Table 2. Distribution of votes by party for or against postponement 1909 and 1915

Note: In percent of total party vote. The Coalition party representatives have been recoded to reflect their party association prior to or after the breakdown of the coalition party.

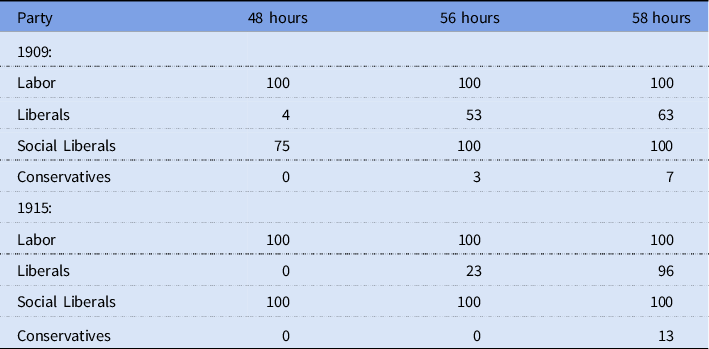

The debate concerning the working-time reductions then got heated. The Conservative Klingenberg argued that regulating work hours could ensure “the greatest misfortune for our industry and crafts. … It is completely monstrous that in this way one would make it a punishable act to work over a certain number of hours” (Stortingstidene 1909: 302). On the other side, the urban Liberal Hansson described the intensity of the employer attack on the majority position in the parliamentary committee. He argued, “It is one of society’s most sacred tasks, that social legislation should take care of the welfare of the general public, the welfare of society, and that this must take precedence over everything else” (ibid.: 305). Other central urban Liberals supported Hansson. Labor MPs, such as Sæbø, argued for an eight-hour workday but would support the committee’s proposal of 10 hours because it would secure the principle of a state-regulated normal working day. In the end, three proposals for regulated hours were roll-called: 48, 56, and 58 hours per week. All three proposals failed to pass, and the 1909 factory revision ended up not regulating hours. Table 3 shows MP-vote distribution by party. Votes for regulated hours revealed a pattern congruent with the statistical results. Socialists voted in unison for all proposals to reduce working time, with representatives noting trade union calls for the same. Similar levels of support were found among the Social Liberals. The Liberals would support only the more conservative option but did not oppose regulation of hours as a matter of principle; most Liberal MPs voted for 58 hours. Nearly all conservative MPs voted against restricting hours.

Table 3. Distribution of votes by party in favor of various hours of work per week, factory act of 1909 and 1915

Note: In percent of total party vote.

In 1915, a revision of the factory law was attempted again with a Liberal government proposal penned by the Social Liberal Castberg in 1914 to set daily work hours to nine for factory workers and limit overtime, with significant increases in overtime remuneration. As in 1909, the law proposed to include workers in small firms, especially craft workers, miners, and agricultural factory workers (dairy production). Castberg and the Social Liberals left government during the preparation of the act, and the Liberal government put forward its revised compromise proposal of 10 hours per day (58 weekly hours).

Initially, it was decided to leave out the broader aspects of employment protection to be evaluated by a worker protection commission and deal only with working time. The law faced stiff opposition. However, with the 1912 election affording the Liberals a 56 percent majority, the combined support of Social Liberals and Labor allowed the Liberals’ preferred 58-hour proposal to pass. The distribution of votes by party revealed the same pattern in 1915 as in 1909, with only Social Liberals and Labor supporting an eight- or nine-hour day.

Agrarian Liberals spoke out against the act and hour regulations, even in the face of a proposal from their own Liberal government. Fearing increased rural depopulation, they also opposed including agriculture in the regulations. The prominent Liberal farmer Trædal noted he would support the 1915 Factory Law because, to a large extent, it excluded agriculture and would not be implemented until 1920. Many things could change between 1915 and 1920, he mused. The landlord Blakstad went as far as spelling out the farmers’ rural–urban mobility concern, word for word:

What will be the effect on Norwegian farming? Even if the law will only apply to industry, it will still draw workers away from rural districts, increasing labor costs for farmers, … harming grain production. … I will end by recommending the postponement proposal. (Stortingstidene 1915: 2108)

What were employers’ and unions’ preferences for the proposed 1909 and 1915 reforms? Using extensive parliamentary records on unions’ and employers’ appeals concerning the reforms’ impacts, I coded whether these appeals argued in favor of, against, or indifferent to postponement, work hours reductions, overtime restrictions and remuneration, and coverage extensions. Employers (firms or organizations) made 203 appeals, and trade unions made 90.Footnote 13 This allowed me to test H1 and H4 concerning trade unions and employers’ preferences for working-time regulation.

Not a single employer spoke out in favor of any of these aspects of the factory acts in 1909 or 1914/1915. Instead, they called for outright postponement. For example, in 1915, following an extraordinary general assembly, NAF stated that they had “unanimously decided … to present the most urgent recommendation to parliament, to not go to treatment of the worker protection act.” This supports H4. Trade unions, on the other hand, made only supporting statements in favor of the reforms, with the AFL stating an eight-hour law “is the only natural response to the strong and just demand of workers from our land for a shorter working day” (Ot. 35 1914: 102). This supports H1.

Did employers manage to influence the Conservative and Liberal MPs’ position? In justifying their postponement vote in 1909, MPs Velo and Erichsen explicitly referenced craft and industry association appeals during the debate (Stortingstidene 1909: 341). One can also find employer influence in the postponement debate, in which Conservative MPs focused on inadequately incorporating employer concerns in the various proposals.

Agricultural interests made statements on the desirability of the factory acts, in line with H6 on farmers. Producers, such as the Skiens and Porsgrunds dairy co-operative, speaking on behalf of 750 farmers, reacted to the 1914/15 proposal:

The proposed worker protection law will, in indirect and direct ways, harm the interest of agriculture. Workers in agriculture will soon demand the same working time – or the same liberty to work – as will be introduced in crafts and industries, or the flight from agriculture will increase at even greater speed. … Work intensity and work competence stands at a considerably lower level [in Norway] than in most other places in the world, and it should therefore be of little interest to pursue factory acts that forbid people to work and promote laziness and daydreaming. (Dokument 49 1915: 99–100)

The Norwegian dairy association later supported this statement, writing that the proposal would “only induce major issues without achieving any benefits for workers” (Dokument 49 1915: 101). Similarly, the national association for milk condensation factories, calling for the postponement of major revisions, claimed implementation “can have the most fateful consequences” (ibid.: 116). Farmers were cognizant of how regulation, even when restricted to factory work, could affect farmers in various ways, including fostering workers’ further rural–urban flight.

These two major reforms work to demonstrate the preferences of farmers, trade unions, and employers in line with expectations and illustrate the mechanisms underlying the specific hypothesis. For example, Conservatives are argued to highlight the need to especially protect urban employers’ interests, and Farmers and rural Liberals the interests of the farmers and their concerns for depopulation of the countryside. The quotes provided herein clearly show that these issues were present in the arguments of representatives for the various actors.

Oral statements in parliament and hearing statements regarding the Worker Protection Law of 1936 and Seafaring Act of 1939

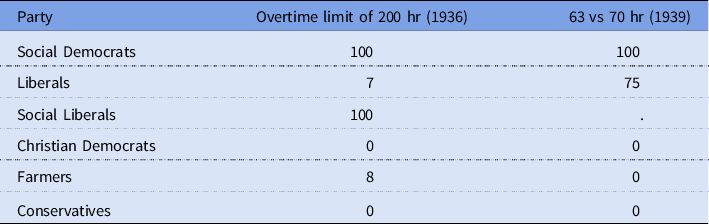

To what extent did party and interest organization support for working-time regulation change following the implementation of proportional representation (1919/1921) and the “kriseforliket” in 1935 between Labor and Farmers usher in a new Labor government as argued by, for example, Iversen and Soskice (Reference Iversen and Soskice2006), Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990), and Kersbergen and Manow (Reference Kersbergen and Manow2009). To investigate this, I used the Worker Protection (Arbeidervern) Law of 1936 and the Seafaring Act of 1939.Footnote 14 Although they were central pieces of legislation, they also illustrated the vote patterns of the newly founded Christian Democratic party and the Farmer party. The Liberal government started preparing the Worker Protection Law in the early 1930s, but it was a Labor government that put it forward to parliament. I focused on the maximum hours (two hundred overtime hours per year) and weekly work hours on Norwegian ships (to 63 from 70). Table 4 shows the votes by party, and Section 3.1 presents additional descriptions of the contended issues.

Table 4. Distribution of votes by party in favor of limiting overtime to 200 hours per year (Worker protection act 1936) and in favor of 63 vs 70 hours of work per week (seafarers act 1939)

Note: In percent of total party vote. Social Liberals failed to be reelected prior to the 1939 vote.

For both acts, Labor MPs voted in favor of reducing hours. The Labor party proposed more generous working-time reductions and consistently voted for these proposals in parliament. Following a pause in negotiations, in which the socialists agreed to support increased subsidies to local transport companies, Liberals voted in favor of the 1939 proposal to restrict hours. In 1936, however, they voted against the proposal to limit overtime to two hundred hours. Why did the Liberal position become more antagonistic? As shown by the votes, Liberals voted in 1936 against limits on overtime, with one exception. To some extent, this reflected policy preferences – restrictions on overtime would set a decisive limit on hours allowed to work, with reductions in normal hours allowing some flexibility. It also reflected that in the 1933 election, the party lost all but one of its urban districts. The only candidate who voted to limit overtime was the single remaining urban representative. In 1939, the party now recaptured four urban mandates. Again, Liberals who voted against the proposals came from rural districts or districts with large shipping interests, supporting H7 of rural liberals being less supportive of working-time reforms.

Conservatives accepted the need to revise the Worker Protection Act but aimed to circumscribe its impact in several ways; the party voted decisively against any overtime limit. The Christian democratic representative did not speak during the parliamentary debate, signaling disinterest and voting against all restrictions on hours.

Going against the Labor government they helped put into office, Farmers voted against hour reductions for seafarers and in the Labor Protection Act. In the parliamentary commissions, the farmer representatives, alone or in congruence with Conservatives and the Liberals, proposed limiting the impact of these laws. For example, they proposed increasing hours worked in certain circumstances to 1.5 hours per day – one hour higher than the socialist proposal of 0.5. Most importantly, the Farmers sided against the Labor proposal that workers would accrue the right to vacation (a new aspect of the 1936 law) after six months of work (instead of the proposed 12 months). The vote was not roll-called (see Innst. O. VI 1936: 16–19).

Employers and unions responded as they had for prior proposals.Footnote 15 The AFL demanded a seven-hour day and 40-hour week, and NAF remained antagonistic to work reductions (Dokument 1 1936: 11, 24, 27). One change was now clearly reflected in the unions’ arguments: Working-time reductions through work-sharing were now promoted as a remedy against the massive unemployment the great depression caused. The parliamentary committee considered the NAF’s protest against limiting yearly overtime to two hundred hours (Innst. O. VI 1936: 16). In short, neither union nor employer preferences changed following the signing of the basic agreement or the Labor government’s coming to power. Instead, both actors’ statements fell in line with H1 and H4.

In short, I find no evidence of party or interest group preferences changing with the adoption of PR in 1919 or the formation of the Worker-Farmer coalition of the 1930s. Instead, political divisions on working time continued to fall along class and sector of the economy.

Summary cross-country results

The cross-country analysis was undertaken using data on normal weekly hours from 32 democracies between 1870 and 2010, as shown in Appendix C given space constraints. In the most conservative model, including time trends, country dummies, and controls for economic factors, executives from Liberal, Religious, and Socialist parties differed from Conservative parties by two to three regulated hours, with overlapping confidence intervals for the independent variables. This would appear to support H2 of socialist parties reducing hours, H3 that liberals (H3) and social liberals (H8) are as likely as socialist to reduce hours, and H5 that conservative are unlikely to reduce hours compared to socialists but go against H9 as religious parties working against working-time reforms. However, results depend on how working-time regulations are measured. The dependent variable takes the value 72 in the case of a country not regulating its hours (no law), and this choice of baseline could influence the results.

Moving instead to models explaining the likelihood that a country in a specific year adopts a reform to reduce hours, I find that compared to conservatives, only executives from socialists’ parties are significantly associated with introducing working-time reforms. That is, religious party executives are not significantly likely to adopt reforms reducing hours once I correct for the choice of baseline (why the choice of baseline could influence results is further explained in Appendix C). In short, the cross-country results provide some non-robust support for religious leaders reducing hours (against H9) and liberal and Social Liberal executives doing the same (H3/H8), leaving only socialist executives robustly associated with reforms that reduce work hours (H2) compared to Conservatives (H5).

Conclusions and implications for future research

In the combined findings from the various analyses using fine-grained historical data on working-time reforms, several patterns stand out enough to form some preliminary conclusions about the roles of party families, employers, unions, and farmers in working-time reforms.

Table 1 provides an overview of the hypothesis and findings, but I here provide a quick summary. First, unions and employers held diametric views on working-time regulation. Of the several hundred appeals consulted, no employer spoke out in favor of regulation. This supports expectations that trade unions supported, and employers resisted, working-time regulations (H1 and H4, respectively). Second, Labor and Social Liberals played a decisive role in pushing and voting for reforms reducing working hours, supporting H2 and H8 that socialist and social Liberals promoted working-time reforms. Cross-country results indicated that this association can be generalized for the Socialists. Third, Labor can be clearly distinguished from Liberals and Conservatives. The former accepted some level of regulation, whereas the latter outright opposed almost all regulation. Both were, however, less likely to support regulation at the level of the Labor. Therefore, I must reject the hypothesis that Liberal parties were equally likely as socialists to support regulations (H3). However, the results align with the expectation that conservatives to a greater degree resist working-time regulations than socialists – supported also by the cross-country results. Fourth, in line with H6, farmers resisted working-time regulation, even if the regulations applied only to factory work. Fifth, intra-liberal divergences tended to originate in whether representatives were less or more linked to agrarian interests, with farmers forming within-party opposition to the leadership. This explains why the Liberal party’s social reforms failed to garner intraparty support and support H7. Sixth, evidence for the religious parties’ role is mixed. However, weighing non-robust findings on their role from the cross-country results with the clear and consistent results from the Norway case indicates that religious parties themselves did not promote working-time reforms.

What broader implications can one draw from these findings?

First, in line with previous claims by Burgoon and Baxandall (Reference Burgoon and Baxandall2004), working-time reforms are a politicized issue with clear partisan differences. This means that variation in the speed and strength of reforms cannot be reduced to macro-structural forces alone, such as political institutions or trade dependence (Burgoon and Raess, Reference Burgoon and Raess2009; Huberman, 2012). Instead, parties pursued substantially different policies depending on their class composition and the need to mobilize other social groups. This means that cross-national differences in working- time reforms are shaped by the party in power. This is not to say that macro-structural factors are unimportant, but the findings emphasize in my opinion the importance of political parties in working-time reforms.

Second, the results illustrate the importance of considering how policies can take the form of bridge policies (De Sio and Weber Reference De Sio and Weber2014). Working-time regulation allowed party strategists in liberal and labor parties to bridge an electoral coalition of middle- and lower-income employees. In this way, the politics of working time does not follow a strict left-versus-right logic (e.g., Alesina et al. Reference Alesina, Glaeser and Sacerdote2005) with especially the Social Liberal and, to some extent, the liberals promoting working-time regulations. Instead, working-time politics become structured along class based on the employment relationship, with employees standing against employers. If the socialists had failed to outcompete the Social Liberals, the latter could have played a similar role as the socialists in promoting working-time reforms.

Third, the results do not align with Burgoon and Baxandall’s (2004) or, by extension, van Kersbergen and Manow’s (Reference Kersbergen and Manow2009) studies on Christian democratic parties. Instead of Christian Democrats promoting working-time reforms, the results from the RCV data show instead the opposite pattern. Given the strong emphasis of Burgoon and Baxandall (Reference Burgoon and Baxandall2004) on Christian Democrats as promoting “welfare without work,” this result appears puzzling. I think the puzzle might be solved by more clearly separating religious nomination from electoral incentives faced by religious parties. The religious parties included in the Norwegian case were all small, meaning that they did not end up as the large cross-class highlighted by Kersbergen and Manow (Reference Kersbergen and Manow2009). Possible future micro-studies on countries such as Germany could perhaps tease out the roles played by a religion and electoral incentives faced by cross-class religious parties.

Fourth, this study underlines the importance of the farmers’ and their organizations’ roles in setting working-time policy. Contrary to the seminal studies of Baldwin (Reference Baldwin1990) and Manow (Reference Manow2009), in which farmers demanded inclusion of agriculture in welfare schemes, I find that farmers worked actively to restrict any reforms that might shift the balance in favor of industry. Working time was perceived as a policy that would reduce rural labor supply, raising farmers’ costs in an acute international competition. Farmers responded accordingly. Furthermore, there is no indication in the data material that farmer–labor alliances of the 1930s (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990) secured working-time reforms. Instead, labor governments had to turn to the Liberals to secure support both for the Worker Protection Act of 1936 and the seafaring working-time law of 1939. The results, therefore, indicate a simple but key point: Countries in which agrarians reached a dominant position or became key players in politics, such as the Farmers in Norwegian politics, were more likely to see less pro-leisure reform. Ascertaining the validity of this claim would require cross-national studies on farmers’ roles as a class and a party beyond what is here done.

In conclusion, the paper argues that parties’ preferences for working-time reform are shaped by their links to sector and class constituencies. Lower and urban middle-class workers demanded regulation, while employers and farmers opposed it. This resulted in worker parties supporting working-time reforms while conservative and farmers’ parties formed a staunch opposition based on their class and sector differences.

Future research should focus on whether the established partisan patterns still hold in post-industrial economies. The new politics of the welfare state have changed drastically from those of the old (Häusermann et al. Reference Häusermann, Picot and Geering2013; Pierson Reference Pierson1996), with parties adapting to changing electorates and pressures for new reforms with deindustrialization and low growth (Skorge and Rasmussen, Reference Skorge and Rasmussen2021). How do old protagonists of working-time reforms fare? Has reduction in hours been exchanged for demands for working-time flexibility? Alternately, how does legislation constructed for male, full-time, and industrial workers attune to the life situation of a heterogeneous workforce with increasing self-employment? Further, it would be interesting to find out whether farmer parties have changed their policies as farmer parties transformed into center parties and encompassed more parties of rural defense against the center. Finally, the newcomers – the green parties and their focus on alternatives to the growth and mobilization of urban radicals – should be interesting cases for future study (e.g., Sanne Reference Sanne1998). Such studies as mentioned here would shed light on whether the findings of this paper hold for the future.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2023.18

Acknowledgements

For comments on an earlier version of this paper, I am grateful to Jonas Pontusson, Damian Raess, Alexander Kou, Øyvind S. Skorge, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Carsten Jensen, Kees van Kersbergen, Jonas Kraft, Axel West Pedersen, Henning Finseraas, and Tobias Schulze-Cleven. The same goes for the attendees at the comparative politics seminar at Aarhus University, The Welfare State and Social Policies around the World Workshop at the University of Oslo, and the internal-staff seminar at Geneva University. Finally, I would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback and suggestions and the editors for additional suggestions.