Many aspects of shape, decoration, and subject matter on the François vase recur in subsequent vase-painting. It is not entirely impertinent to call it “the mother of all Athenian vases.” Three features of the François vase in particular warrant further investigation. They include the eye contact afforded the viewer by Dionysos, the incorporation of painted vases within a vase-painting, and the thematization of the relationship between Thetis and Hephaistos as a model for the relationship between the artisan and patron. Those features are of interest because they operate in part at least subjectively: that is to say, they evoke or conjure the artist behind the vase-painting. In this chapter, I examine the development of those features on three extraordinary vases.

The Solipsistic Spectator in the Picture on an Aryballos by Nearchos

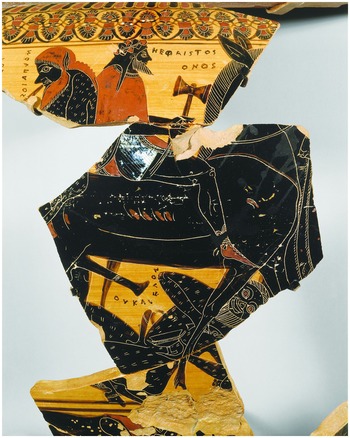

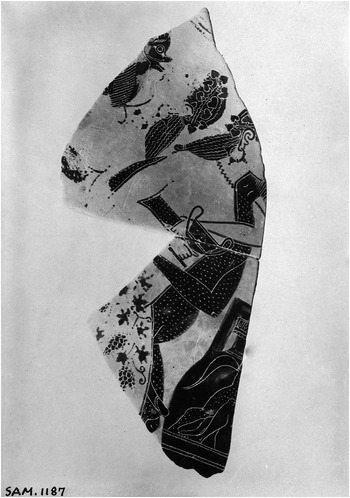

On the François vase, the figure of Dionysos acquires much of its semantic value from the direction of its gaze (plate XV, figure 26). By turning away from the unsympathetic figures in his immediate vicinity, and making eye contact with a sympathetic friend occupying the position of the spectator of the vase, he arguably conjures the presence of his associate, the artisan Hephaistos, in our midst. We are on the side of the artist. This is not the only vase-painting of a figure making eye contact with the spectator, inviting him or her to see him- or herself in a personal relationship to the represented figure despite differences in identity. On an aryballos by Nearchos of around 560 BC (figure 34), three carefully painted silens are depicted as team masturbators. The care with which the little image is constructed extends to the inscribed names of the figures, chosen as commentary on the depicted activity: Τερπεκελος, Δοφιος, Φσολας, Terpekēlos, Dophios, Phsōlas: “shaft-pleaser,” “wanker,” and “hard-on.” The composition is dominated by the central figure of a silen, squatting and gripping his massive member with both hands, shown fully frontally with respect to the spectator’s point of view. To either side of the central figure, two identical silens are depicted in profile view, facing each other. The silens to right and left are mirror images of each other, so to speak. The symmetry between them suggests that a similar arrangement exists between the central, frontally oriented silen, and whoever he makes eye contact with. Who does the silen see as he stares precisely at the location taken by the spectator but, like his brother to the left or right, another solipsistic silen?1

Figure 34: New York 26.49, black-figure aryballos, ABV 83,4, attributed to Nearchos, BAPD 300770. Purchase, The Cesnola Collection, by exchange, 1926.

How this imaginative engagement with a viewer works in detail was lucidly explicated by Richard Wollheim. There is a fundamental distinction, he posited, between a spectator of a picture and a spectator “in” a picture. The spectator of the picture (or external spectator) occupies the space where the work of art is to be seen, such as an ancient symposium or modern museum. By internal spectator, Wollheim means an imaginary figure whose presence and identity or character is implied by the action(s) and gaze(s) of the painted figure(s). The internal spectator shares the virtual space inhabited by the other figures within the representation–but happens not to be visible to us within the “slice” of the virtual space given to us by the picture.2 A powerful example is provided by Velázquez’ Las Meninas (plate II) with which this book began: the Infanta Margarita, Velázquez, and several other figures in the painting have paused to acknowledge visually the presence of the king and queen of Spain. The king and queen are not depicted within the painting, but it is clear from the actions of the figures within the painting that the royal couple occupies a position more or less identical with that of any viewer of the picture. In trying to figure out what the en face figure within a painting might be looking for in the vicinity of the external spectator, one relies on inference. One builds a hypothesis out of the information contained within the image about the character of the represented figure and the situation in which the figure is found–supplemented perhaps by information about the character or type of figure derived from other paintings, literature, and common knowledge.3 In the case of Las Meninas, one infers from the deference paid to the unseen protagonists, even by a princess, that they can only be the king and queen of Spain.

Wollheim was interested not in just any unrepresented, internal spectator, but only those who occupied the same point of view as that taken by the external spectator. His interest lay not merely in how formally a painting may imply the presence of an unrepresented figure. It lay rather in how such a figure might afford the external spectator “a distinctive access to the content of the picture.”

This access is achieved in the following way: First, the external spectator looks at the picture and sees what there is to be seen in it; then, adopting the internal spectator as his protagonist, he starts to imagine in that person’s perspective the person or event that the painting represents; that is to say, he imagines from the inside the internal spectator seeing, thinking about, responding to, acting upon, what is before him; then the condition in which this leaves him modifies how he sees the picture … In a licensed way he supplements his perception of the picture with the proceeds of imagination and does so as to advance understanding.4

Formally, the little vase-painting on the aryballos in New York (figure 34) encourages the viewer to see him- or herself in the indiscreet, indecent silen. But strictly speaking, the identification is impossible ontologically, physiologically, and, some might feel, ethically. The only possible responses are offense or amusement. The important point is that the responses potentially concern two different aspects of the image. One is the proposition itself: looking at the solipsistic silen, does one fantasize about a life free of shame and devoted to self-pleasure? Or does one fear relinquishing self-control as a slippery slope with a heap of masturbators at the bottom? In other words, how does the viewer respond to the ethical proposition that he or she is no different from a silen? The other aspect of the image in which the viewer may find either offense or amusement concerns its creation. If a viewer is deeply offended or highly amused by the proposition that he or she is nothing but a shameless silen, he or she may well ask, indignantly or admiringly, “who is responsible for putting me in the position of identifying with such a scurrilous fellow?” The question draws attention away from the three silens and invites speculation about who made the image.

Interestingly enough, on the aryballos, the vase-painter provided an answer to the question in the very location where it is most likely to be desired. Immediately beneath the scene of masturbating silens, in a prominent patch of black glaze, is incised the signature Nέαρχος ἐποίε̄σέν με, Nearchos epoiēsen me, “Nearchos made me.”5 The use of the personal pronoun, me, to refer to the vase is attested already in the earliest signatures on Athenian vases, those of Nearchos’ immediate predecessor Sophilos. But its presence here in the emphatic final position, immediately below the silen directly addressing the viewer, encourages one to wonder if me refers also to the fictional creature. The writing elsewhere on this aryballos seems particularly self-aware, for some of the inscriptions are not Greek and perhaps meant to be understood as the sounds or foreign speech of the little Pygmies and cranes depicted around the rim. But the writer is far from illiterate, for other inscriptions, such as the all-too-evocative names of the silens or the signature, are very good Greek.6 Just as one makes eye contact with the emphatically frontal silen and realizes that the silen sees someone just like himself in the viewer, one is also invited by the writing to think about how the viewing experience was created, and who was responsible. Word and image together stack the en face silen, the beholder, and the artist one on top of the other. Might one even feel a momentary kinship with the artist, when one realizes that Nearchos, at the moment he was incising his name on the newly fired vase, was occupying exactly the same position as the viewer who looks at the image and reads the signature? Nearchos was not only the creator of this vase but also its first viewer.7 This small vase, with its representation of little Pygmies, packs a big subjective punch.

The Eye Cup Psiax

An even more radical attempt to employ the frontal face for the evocation of the artist in our midst occurs on two Athenian bilingual “eye cups.” This type of decorated cup, popular in the last third of the sixth century BC, features a pair eyes, eyebrows, and, sometimes, a nose and/or ears on each exterior surface. On a cup in Munich and a cup in New York, above the nose between the eyes on one exterior surface, there is the inscribed name Φσιαχς, Phsiaxs, “Psiax” (e.g., figure 35). The name is familiar from the artist’s signature, Psiax egraphsen (or egraphe), that occurs on two contemporary Athenian alabastra. What is the significance of the inscribed name on the two cups? The cups are related in style of painting to the vases signed by or attributed to the innovative vase-painter Psiax. But the name of the artist is not accompanied on these cups by a verb claiming credit for the painting of them.8 Because it is not clarified by a verb of making or painting, the inscribed name “Psiax” is open to other interpretations. The most familiar function of the inscribed name in vase-painting is a label identifying a represented figure. Typically, the inscribed name begins at the head of a figure, who is represented in his/her entirety on the body of a vase (e.g., plates I, III, and many others in this book). In the case of the two cups bearing the name “Psiax,” however, there is no represented figure of the usual type–that is, “within” the figural world of the vase-painting–in the vicinity of the inscription. There is just the pair of eyes and nose of the face of the eye cup itself. In this case, the name “Psiax” begins not adjacent to the head of the represented figure, but within the space of the head itself.

Figure 35: New York 14.146.2, red-figure eye cup, ARV2 9,1, perhaps Psiax, BAPD 200038. Rogers Fund, 1914.

For many years, the eyes on an eye cup were understood to be apotropaic in function. The difficulty with that interpretation is that it is unclear what is being magically protected by the pair of eyes: the cups themselves, the wine contained in the cups, or the users of the cups? More importantly, the theory did not explain the decoration of the eye cup in its entirety. The earliest eye cups almost invariably include a nose in addition to the eyes; some include ears as well. The primary objective of this scheme of decoration is the transformation of the round exterior surface of the cup into a face.9 J. D. Beazley recognized that the eyes on the cup sometimes belonged to the gorgon Medusa (the link being the small dots occasionally appearing between the eyes on the cup as well as on gorgoneia). This marked a significant advance in the understanding of the pictorial phenomenon, because it acknowledged the possibility that the face of the eye cup might represent the face of a particular individual. Subsequently, it was recognized that the eye cup often represents the face of a silen or a nymph and sometimes perhaps even depicts the face of Dionysos.10 The pair of eye cups bearing the label “Psiax” between the eyes was created and circulated amid two expectations: one is that the eye cup sometimes represented the face of a specific individual; the other is that a name written on a vase, unaccompanied by a verb or adjective, identified a figure represented on the vase. In such a milieu, it is a small interpretative step to suggest that the writing on the two cups transforms the generic face of the eye cup into the specific face of Psiax. And any viewer familiar with the occupation of Psiax is presented with the proposition that he or she is looking at the face of the very artist who created the cups.

The eye-scheme of decoration incorporates elements of the very shape of the cup into the representation of a face. John Boardman nicely captured the way in which the eye cup in its entirety is transformed into a face when the cup is used for drinking: “consider one raised to the lips of a drinker: the eyes cover his eyes, the handles his ears, the gaping underfoot his mouth.”11 Labelling the face of the cup “Psiax” sets up a relationship of the closest possible intimacy between the artist’s name and the cup, both potting and painting. Psiax is not just a figure within the decoration of the cup; his face is coextensive with the very cup itself. These are among the most sophisticated “self-portraits” of an artist that I know. It is as if an easel-painter had figured out how fill with himself not just an entire canvas but also its frame. The cups may be compared to the poetry of Hipponax. The cups effect a grotesque “portrait” of a specific artist, by employing an existing scheme of pictorial decoration with links to the imagery of the gorgon Medusa. Like the (self-)portraits of Hipponax, the representations (or self-representations) of Psiax identify the vase-painter with the power of his particular medium. If someone asked, “what does Psiax look like?”–the eye cups answer, “he looks like one of his own cups.”

Left Hand and Right Hand in Euphronios

Let us consider one additional possible example of pictorial allusion to a painter via the motif of the frontal face. On the krater in Munich (plates III, V), the disengagement of Thōdēmos from his friends, visually, in terms of eye contact suggests that he is no longer aware of them. One explanation of his alienation is suggested by the lifting of his cup to his lips; perhaps he is too drunk to recognize his friends. Two aspects of the figure of Thōdēmos, however, suggest that the frontal face is not exclusively suggestive of disengagement from the garrulous (unrewarding?) company of the symposiast-manqué, the vase-painter Smikros and his associates. First of all, the action that Thōdēmos is performing, lifting a drinking cup to his lips, is the action that the ancient beholder of the vase may well have simultaneously been performing, or that a student of vase-painting can imagine him- or herself performing while looking at the vase in the Antikensammlungen. The figure of Thōdēmos can been understood to be a kind of mirror image of the symposiast looking at the krater. The potential reflexivity inherent in the image contributes to the sense that Thōdēmos is not merely turning away from his own company, but also directly addressing the viewer.

At the same time, holding a cup before one’s eyes is something that a vase-painter does, as he examines the cup he is decorating. That reading of the image is encouraged by a feature of the right hand of Thōdēmos: although it is attached to the right arm, it is not a right but a left hand. Richard Neer nicely explained why this might be so: “faced with the problem of how to draw such a hand, Euphronios did the most natural thing in the world: he held his own left hand before himself at the appropriate angle, and with his right hand drew what he saw.”12 In chapter one, it was noted that left hands are attached to right arms, or vice versa, in several vase-paintings attributed to Euphronios or signed Smikros egraphsen (plate I, plate XI). In those vase-paintings, it is difficult to see what semantic contribution might be made by the reversal. In those cases, perhaps the reversals were not noticed by the artist. In the history of art, however, features hitherto unnoticed by an artist can become a conscious part of future work. This is what Richard Wollheim called “thematization:” “the process by which the agent [or artist] abstracts some hitherto unconsidered, hence unintentional, aspect of what he is doing or working on, and makes the thought of this feature contribute to guiding his future activity.”13 Let us suppose that, prior to the painting of the krater in Munich, Euphronios (or someone else) noticed that he sometimes attached a left hand to the right arm, and so, when he painted the krater, Euphronios chose to paint a left hand on the right arm of Thōdēmos, in the manner described by Neer. Is there any independent evidence to suggest that this procedure might have been understood meaningfully? In the history of art, mirror reversal crops up occasionally in self-portraiture. In those paintings, artists known or suspected to be right handed appear as painting with their left hands. As Zirka Filipczak perceptively noted, while most self-portraits correct the mirror reversal, so that the artists portray themselves as they would appear to a studio visitor, the relatively rare uncorrected mirror-reversed portraits are special. “This identifies the implied viewer with the artist.”14 That is one possible reason why an artist as careful as Euphronios might have deliberately depicted a right hand as the left hand on a figure making eye contact with a viewer–a viewer who, like Thōdēmos, is holding a drinking cup. For the beholder who notices the reversed hand, it is an invitation to hold out his cup in his own left hand and imagine himself in the place of Euphronios, drawing the vase-painting that he is looking at. In this way, Euphronios, like Kleitias, Nearchos, and perhaps Psiax, has made his presence felt pictorially.

One further instance of wrong-handedness occurs the vase-painting signed by Euphronios. In the tondo of a small cup in Munich (figure 36), an armed warrior runs to the right, looking back over her shoulder, at an (unseen) pursuer. It is a female warrior, to judge from the absence of beard and presence of long wavy locks of hair. Around the inside of the tondo is the signature Εὐ(φ)ρόνιος ἔγραφσεν, “Euphronios painted [this].”15 With respect to handedness, what is striking about the image is that the Amazon carries her sword in her left hand and her shield in the right. That is an anomaly, for “there exist no heroes in Greek art who are southpaws,” as Takashi Seki memorably remarked. He took the picture to be the result of an unintentional error in drawing.16 The picture of the left-handed Amazon, however, is not unique. A cup in Bochum attributed by Beazley to a follower of Euphronios, the Hermaios Painter, also depicts an Amazon running to the right, looking back, torso seen from the front, sword in the left hand, shield in the right. In her publication of the cup in Munich, Martha Ohly-Dumm argued that it was the model for the cup in Bochum.17

Figure 36: Munich, Antikensammlungen 8953, red-figure cup, signed by Euphronios, BAPD 6203.

Is the Amazon warrior on the cup in Munich intended faithfully to represent a left-handed warrior, or is the representation “in error”? The picture supplies a clue: the warrior is not always left handed, because she wears her scabbard so that she can reach the hilt of a sword with her right hand. The two customs depicted on the cup–wearing the scabbard so that it opens on the left, and carrying the sword in the left hand–contradict each other. The presence of a scabbard worn “correctly”–in the sense that it conforms to the manner in which scabbards and swords are used elsewhere in Euphronian vase-painting (even among Amazons, e.g., the krater in Arezzo [figure 13])–indicates that Euphronios had not forgotten his ordinary practice. And the painting of shield and sword must have taken a certain amount of time and deliberation. Nevertheless the drawing was completed and the cup was fired, as if what we see is what Euphronios intended. In this picture, then, handedness seems deliberately manipulated in order to create an image that will provide an enjoyable puzzle to the viewer and provoke questions about the relative competence of painters and Amazons. And the deliberate manipulation of handedness within this vase-painting signed by Euphronios encourages credibility in the hypothesis that the painter deliberately depicted a left hand as the right hand of Thōdēmos (plates III, V).

Hephaistos, “Fictive” Vase-Painting, and Artistic Self-reference on a Krater in New York

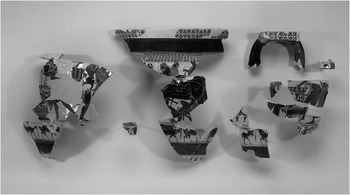

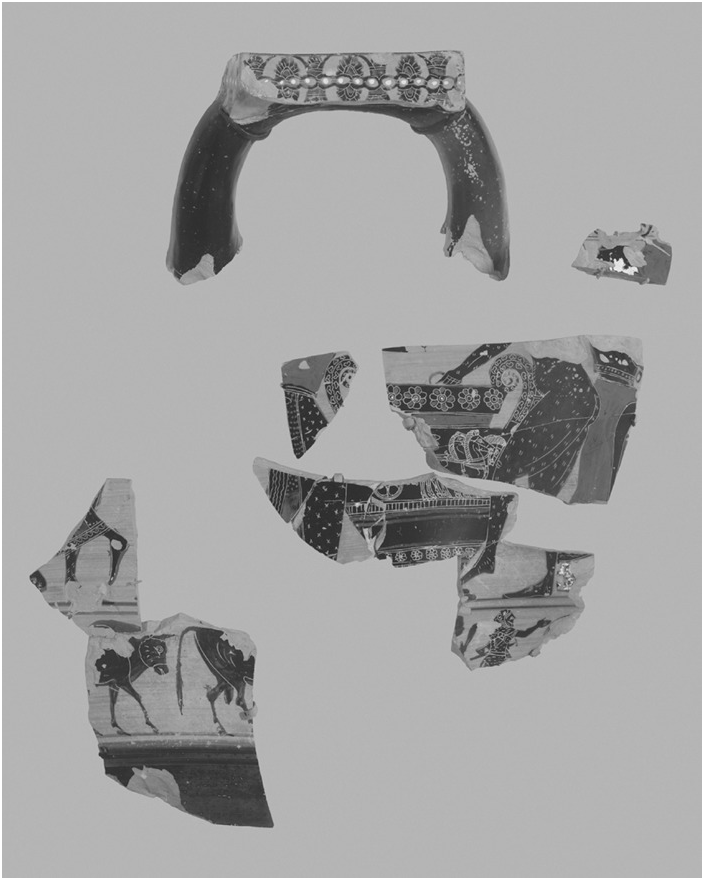

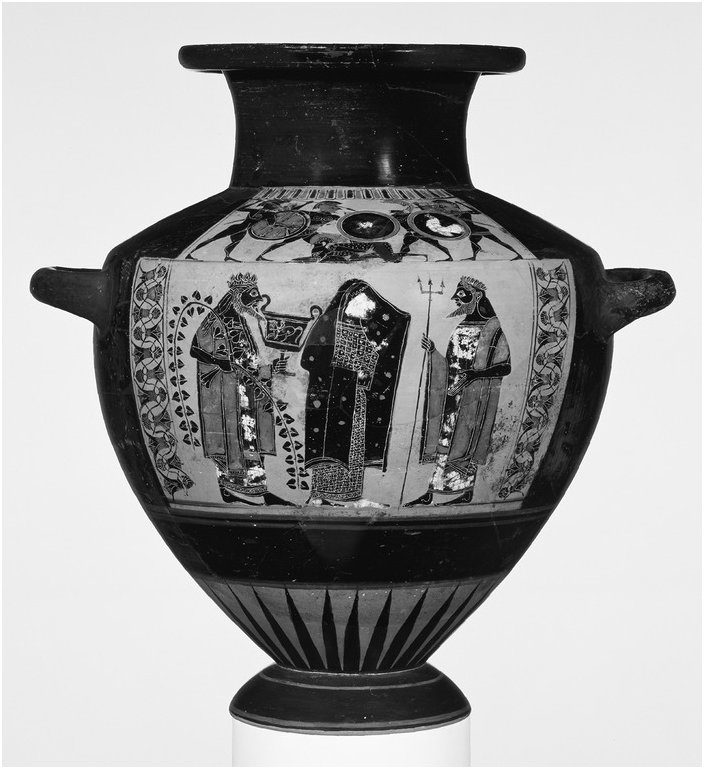

The second vase-painting to employ a form of subjective expression or self-reference familiar from the François vase is an extraordinary representation of the return of Hephaistos. The considerable variety in well-known vase-paintings of this lively subject is unmatched by several innovative features of a very large, recently published black-figure column krater, painted around 560–550 BC, of which many fragments were acquired by the Metropolitan Museum in New York in 1997 (plate XVI, figures 37–39).18 Like the François vase, the fragmentary krater exhibits interest both in the dissolute lifestyles of silens and nymphs, and in the manufacture of fine vases. The fragmentary krater articulates a world that is simultaneously disordered and exquisitely refined. Those are rough outlines of the Archaic persona of the artist or poet.

XVI: New York 1997.388a-eee, 56, and 493, fragmentary black-figure krater, BAPD 46026. Detail: Oukalegon. Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and Dietrich von Bothmer, Christos G. Bastis, The Charles Engelhard Foundation, and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gifts, 1997 (1997.388a-eee). Gift of Dietrich von Bothmer, 1997 (1997.463).

Figure 37: New York 1997.388a-eee, 56, and 493, fragmentary black-figure krater, BAPD 46026. Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and Dietrich von Bothmer, Christos G. Bastis, The Charles Engelhard Foundation, and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gifts, 1997 (1997.388a-eee). Gift of Dietrich von Bothmer, 1997 (1997.463).

Figure 38: New York 1997.388a-eee, 56, and 493, fragmentary black-figure krater, BAPD 46026. Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and Dietrich von Bothmer, Christos G. Bastis, The Charles Engelhard Foundation, and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gifts, 1997 (1997.388a-eee). Gift of Dietrich von Bothmer, 1997 (1997.463).

Figure 39: New York 1997.388a-eee, 56, and 493, fragmentary black-figure krater, BAPD 46026. Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and Dietrich von Bothmer, Christos G. Bastis, The Charles Engelhard Foundation, and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gifts, 1997 (1997.388a-eee). Gift of Dietrich von Bothmer, 1997 (1997.463).

On the central fragment (plate XVI), there are traces of three figures, all of whom push against the boundary of respectful behavior. Although virtually nothing remains of a nymph but for traces of hair tied up with a fillet, her name Φιλοπος[ία], “love of drinking,” is arresting. This is perhaps the earliest extant Athenian vase to contain individual names for silens and nymphs (see chapter seven). The word philoposia and its cognates are attested in literature from the fifth century BC onward, but this is by far the earliest surviving occurrence. In the directory of nymph-names, it is unique. It is probably also countercultural. There were opportunities for women in antiquity to partake in wine-drinking. But Ailian claims that it is “odd” for a woman to be philopotis, “fond of drinking,” and even odder for a woman to be polupotis, a “heavy drinker.” A woman who loved to drink was a male chauvinist fantasy of Old Comedy more than (it seems) a social reality.19 So the name is perfectly suited to the inverted world of the return of Hephaistos. Adjacent to Philoposia, a silen playing the aulos is harmoniously named Μολπαῖος, “the tuneful one.” What is significant about Molpaios is not his name so much as his locomotion. He sits on the back of the mule that carries the god Hephaistos. He is crowding the rider, showing little respect for the god’s higher status or greater physical limitation, and paying no attention to him as he makes music for his friends. The dissolution of divine social hierarchy initiated by the making of the chair for Hera is evident in the silen. Did he even ask Hephaistos if he could have a ride?

A much greater image of impertinence is the silen on the ground between the legs of the mule. Reclining on a wineskin, balancing a stemmed drinking cup on the palm of his hand, his very body language is at odds with the narrative imperative to return Hephaistos to Olympos. He seems to be in no hurry to leave. The cup in his hand suggests that he himself is enjoying a drink. If the rest of the silens and nymphs follow this example, Hephaistos will never return. The silen on the ground does not pay attention to either Hephaistos or Dionysos, but directs his attention in the direction of the spectator. Visually, he declines to subordinate himself to the gods. Compositionally, he occupies the center of the principal picture on the vase, immediately beneath Hephaistos. His visual engagement with the viewer threatens to steal the viewer’s attention away from the god. And his visual interest in the spectator suggests perhaps that, in our place, he hopes to see another reprobate like himself.

In addition to the drinking cup, the silen holds, surprisingly, the shorn hoof of a deer or goat. The picture calls to mind the familiar imagery of the female followers of Dionysos in religious frenzy, dismembering animals. On an Early Classical red-figure vase, for example, a chorus member in a dramatic performance, dressed as maenad, dances with a sword in one hand and the torn hindquarter of a deer in the other.20 The best-known example of that sort of tragedy is the story of the arrival of Dionysos at Thebes as related in Euripides’ Bakchai. The practice of sparagmos, “dismemberment,” as it is called in Greek, is perhaps alluded to on two mid-sixth-century Athenian black-figure vases, one being a beautiful black-figure neck amphora attributed to the Amasis Painter, on which two female devotees of Dionysos carelessly manhandle a hare and a fawn.21 But the fragmentary krater in New York (plate XVI) appears to be the earliest extant explicit instance of sparagmos in Greek art. The fragmentary krater is also the earliest instance by far of a silen participating in sparagmos. In literature, the practice is associated exclusively with the female followers of Dionysos. Silens appear in a handful of vase-paintings in the fifth century in which female figures or the god Dionysos have engaged in sparagmos; but the silens themselves do not handle the torn flesh.22 In fact, on a cup in Fort Worth attributed to Douris, where the Theban women dance with the dismembered parts of the young king Pentheus, a silen directs his attention away, toward the spectator, pantomiming mock horror.23

The image of the silen reclining on the fragmentary krater in New York is extraordinary because it appears to subvert the Dionysiac myth of sparagmos, treating the shorn hoof as if it were a cocktail hors d’oeuvre, and does so at a much earlier date than the cup by Douris. It is possible (though not necessary) to imagine the satire on the Douran cup as informed, directly or indirectly, by the antics of silens in the fifth-century Athenian dramatic genre of satyr-play. But it is not possible to interpret the imagery on the New York krater in the same way, because satyr-play of the parodic or satire sort familiar from literary remains is not attested much before 500 BC.24 The scenario envisioned on the earlier vase appears to be an original visual invention on the part of the artist.

As if to confirm the visual impression of irreverence made by the pose and possessions of this silen is his name, which is written on the vase. It is “I don’t care” (Οὐκαλέγο̄ν, from οὐκ ἀλέγω). Perhaps unsurprisingly, Oukalegōn is not attested in the Lexicon of Greek Personal Names. It does occur once in Greek poetry, as the name of one of King Priam’s elderly associates, who sit on the wall of Troy, watching the battle below, chattering like cicadas (Homer, Iliad 3.148). Virgil remembered the name when he identified the owners of houses of Troy set on fire by the Greeks (Aeneid 2.312).25 But no figure bearing the personal name “I don’t care” is more appropriately so called than the silen on the fragmentary New York krater, who relaxes on a cushion, blithely drinking his wine, enjoying the exotic raw flesh that he stole from the maenads, oblivious to the resolution of the Olympian conflict occurring around him. Moore suggested that the fragmentary krater depicts a different moment in the story of the return of Hephaistos than the François vase. It is the moment before the drinking party has ended, when Hephaistos has just now been placed on the mule, and the procession to Olympos begins to form up.26 Perhaps. But Oukalegōn suggests that the pictorial emphasis is not chronological but thematic: it is in the nature of the return of Hephaistos as a story to disrupt the best-laid plans.

Where is the pictorial emphasis on artistry related to potting and vase-painting? It lies in the substantial pictorial interest in the pottery used by the represented figures. Fragmentary though it is, the krater in New York contains no fewer than seven representations of vases. They stand apart from many other depictions of vases for their meticulously rendered detail. On the basis of numerous comparisons between the represented detail and extant early sixth-century painted vases, it was possible for Werner Oenbrick to demonstrate that the depicted vessels are ceramic vases.27 To a certain extent, the fragmentary krater is a vase-painting about vase-painting.

In roughly the center of the principal image on the vase (plate XVI), in the hand of the visually arresting silen named “I don’t care,” is a stemmed drinking cup drawn with impeccable care. Its lip is carefully offset from the contour of the body, the stem is set off from the bowl by a pair of incised lines, and a band of ornament around the top of the bowl is indicated by a pair of incised lines within which there is a series of short incisions. From a distance, the band of ornament suggests figural decoration or inscription. All of those features unambiguously call to mind a Little Master cup of the band-cup variety. As the band cup first appears around the time when the fragmentary New York krater was decorated, the cup held by the silen named Oukalegōn is the latest in ceramic fashion.

Under one handle of the vase, a silen and nymph attend to an enormous volute krater (figure 38). Under the opposite handle (figure 39), a silen and another figure (a nymph?) are busy at a second monumental krater (perhaps another volute krater, but possibly a column krater, like the fragmentary vase itself). The silens and nymphs are refilling the krater, mixing water with the wine, and decanting. Even the utilitarian vases used for those operations are (depicted as) decorated. The two kraters depicted on the New York vase are the earliest known instances of figure-decorated vases represented on a vase. They are also the most magnificent pictures of vases in all of Athenian vase-painting. The handles of the volute krater are decorated with incised vines of ivy. Its black rim is ornamented with rosettes. Each flower has a white dot in the center, and alternating petals painted red. The neck of the volute krater is carefully delineated from the offset rim above, and the shoulder below, by incised lines bounding a broad red band. On the shoulder and body of the volute krater is an ambitious figure scene, a representation of a (vase-painting of a) four-horse chariot. The manes of the horses, the reins, and the wheels of the chariot are meticulously detailed in incision, and the broad collars of the horses are picked out in added red color. The figure scene is bounded below by an incised band of pattern, then red lines, a wide black band, incised lines, a second band of rosettes, more incised lines, and, finally, base rays. All of this detail occurs in a vase-painting of a vase-painting. The other krater depicted on this vase, either a volute or a column krater, is decorated in a comparably lavish manner.

The prominence given to the kraters in the fragmentary vase-painting emphasizes the importance of wine within the underlying story of the return of Hephaistos (as Mary Moore rightly noted). But the extent of the attention paid to vases within the vase-painting transcends narrative significance. The extensive detail lavished on the two depictions of kraters serves to identify the depicted vases as painted pottery very like the large krater that bears their depictions. The preserved height of the fragmentary krater of 71.8 centimeters means that it must have been nearly waist high when it was whole. This is roughly the height of the monumental kraters depicted on the vase, to judge from the silens and nymphs around them. The actual fragmentary krater is ornamented in a manner that is similar to the decorative schemes of the two “fictive” kraters: a large figure scene around the upper part of the body, a pattern band around the rim, broad band of plain glaze around the neck, tongues around the shoulder, a broad band of glaze around the lower body, and base rays. The different zones of decoration are separated from each other by pairs of lines. Some of the motifs decorating the fictive kraters differ from those on the real krater (chiefly, bands of rosettes in place of lotus and palmette chains), but the motifs on the depicted vases can be found on other more or less contemporary vases. The color schemes are not always the same, but that is presumably because the vase-painter would have had to employ the reserve technique in order to suggest the unpainted areas of a real clay vase, and the reserve technique was very rarely used in vase-painting of this period. The important points are that the vase-painter has attempted to indicate unmistakably, first of all, that the vases depicted on the fragmentary krater in New York are clay vases of the very same style as the real krater itself and, secondly, that the depicted vases are as lavish, ambitious, and impressive as the vase on which they are painted.28

Silens and Nymphs Watching Themselves on Vases

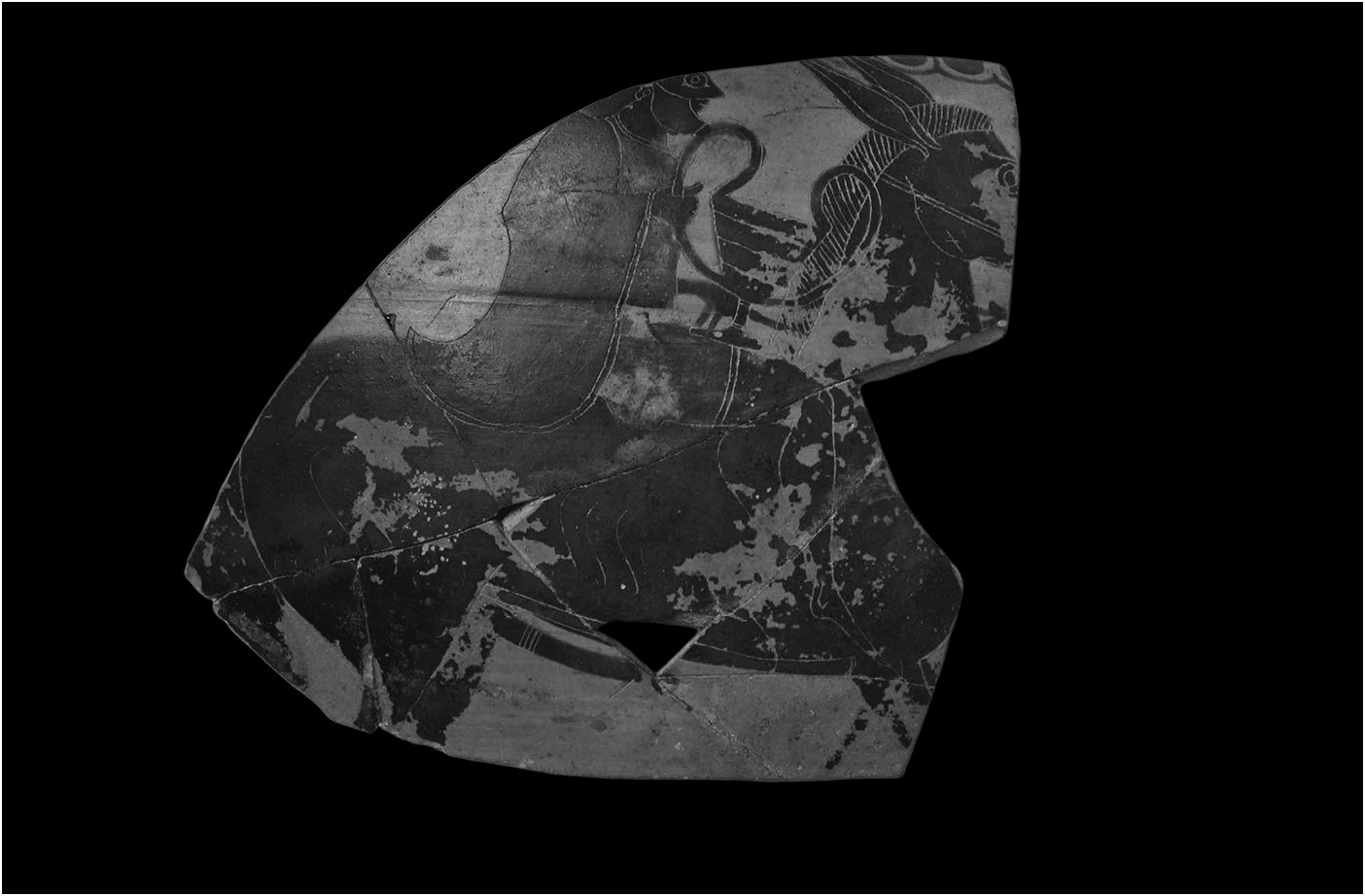

The early examples of the rare pictorial motif of painted vases on painted vases are associated, thematically, with Dionysos. One occurs on a tantalizingly fragmentary amphora on Samos attributed to the Amasis Painter and dating around 540 BC (figure 40).29 Of the main picture, one surviving sherd shows a pair of silens and nymphs walking amorously arm in arm. Unusually, the nymphs are drawn in outline technique so as to appear nude but for earrings and ivy crowns. The silens seem not unaware of the attractions of their partners; one is exhibiting self-control but massively erect, while the other has partially given in to his desire, has picked up the nymph, and kisses her. On the fragment on Samos, there is also a representation of a magnificent figure-decorated column krater. The representation suggests that it is a very large vase, for it comes up in height to the elbows of the silens and nymphs. It is carefully incised so as to appear to be a figure-decorated black-figure krater. Around the vertical surface of the mouth is an incised pattern representing a band of tongues, a familiar form of painted ornament. Represented on the body of the vase is, it seems, a picture of a silen sexually accosting a sleeping nymph.30 The same basic theme is unfolding in the vase-painting and in the vase-painting depicted in the vase-painting. The carefully decorated krater is not the only feature of the vase-painting to invite attention to the theme of vase-painting itself. The technique used to depict the nymphs on the body of the amphora (outline technique) stands in contrast to the techniques used to represent nymphs on the shoulder of the amphora (black-figure technique; not visible in the photo) as well as the nymph depicted on the depicted krater (incision). Because the represented figures are the same type of being in every case (nymphs), what stands out as worthy of notice is the difference in the techniques of painting of them.31

Figure 40: Samos K898, black-figure amphora fragment, ABV 151,18, Amasis Painter, BAPD 310445.

The fragment on Samos, incomplete as it is, has big implications. One is that silens and nymphs enjoy looking at vase-paintings of themselves. They see themselves the way we see them, as celebrated subjects of art. The fragment conveys the sly idea that Athenian vase-painters or their dealers managed to penetrate the mythical world of Dionysos and his followers, an infinitely lucrative if unfortunately imaginary market.32 What is odd about this is the general impression that silens and nymphs, in their lack of clothes and possession of rustic paraphernalia like branches and wineskins, represent a way of life predating all technology. Do silens and nymphs have the know-how, facilities, and patience to make and decorate fine vases? Taking the image on the fragmentary Samian amphora at face value means that someone within the mythical world of Dionysos and his followers painted vases. Who could that be if not the mythical craftsman Hephaistos? Indeed, one might even wonder if the amphora from which this fragment comes did not depict a return of Hephaistos. Several features of the fragment support this possibility. The two pairs of silen and nymph are moving from left to right, as if in procession. The leftmost pair recalls the silen carrying the nymph in arms in the return of Hephaistos on the François vase (figure 25). And the large, figure-decorated krater recurs in the representation of the return of Hephaistos on the earlier fragmentary krater in New York (figures 38–39).

Several early examples of vase-paintings of painted vases are representations of figured kantharoi held by the god Dionysos himself. The earliest and most magnificent example occurs on a black-figure hydria (figure 41) related stylistically to Lydos and nearly as early as the fragmentary krater in New York.33 Poseidon stands opposite a female figure. She unveils herself before him as if before her husband. The gesture suggests that she is Amphitrite. To one side stands Dionysos, a witness to the marriage of the sea god and his consort. The witness makes sense, for the union occurred, according to one late literary source, on the island of Naxos, where Dionysos spent considerable time.34 In this image, Dionysos holds a kantharos of enormous size, in Starbuck’s terminology, a “vente.” On the body of the depicted kantharos, carefully bounded by pairs of incised horizontal lines, is an incised design of a horse and rider. Where would Dionysos have acquired a vase of such splendor? The parallel story of the origins of the golden amphora-urn of Achilles–originally a gift from its creator Hephaistos to the god Dionysos in thanks for hospitality on Naxos–points to Hephaistos as the source of the magnificent kantharos of Dionysos. But the figural decoration of horse and rider is among the most popular motifs in contemporary Athenian black-figure vase-painting. The figural decoration collapses the distinction between Hephaistos’ divine creations and contemporary, artisanal pottery and vase-painting.35

Figure 41: Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, 86.AE.113, black-figure hydria, wider circle of Lydos, ca. 550 BC. BAPD 79.

Primitive Connotations of the Kantharos and the Art of Hephaistos

One additional argument links Hephaistos to the kantharos of Dionysos. The carinated shape of the kantharos held by Dionysos on the hydria in Malibu (figure 41) may have called to mind Etruscan pottery; and Hephaistos had associations with “primitive” ethnic groups like the Etruscans. In Athenian pottery, the carinated kantharos (technically known as Type A1) is not attested much before the second quarter of the sixth century BC. In Etruscan bucchero pottery, closely comparable forms occur already in the seventh century and were well known in Greece as exports in the sixth century. A good case has been made that the Athenian shape derives from the Etruscan.36 At the same time, the carinated kantharos was closely associated with Dionysos from its first appearance in Athenian pottery. Several of the earliest representations of the carinated kantharos within Athenian vase-painting depict the vessel in the hand of the god.37 Within Athenian vase-painting, the kantharos is not exclusively used by Dionysos: it occurs in several early sixth-century representations of the wedding of Peleus and Thetis (figures 26, 28) or komoi; it is used by Herakles in vase-painting of the later Archaic and Early Classical periods. But the visual association between the kantharos and Dionysos is strong.38

Axel Seeberg once suggested that there was a link between the association of the kantharos with Dionysos, on the one hand, and its associations with Etruria, on the other. Noting the existence of the shape in Etruscan bucchero pottery, and remembering the mythical encounter between Dionysos and the Etruscan (or Tyrrhenian) pirates, the kantharos, he wrote, “calls to mind the god at the Anthesteria fresh from his adventures with the Tyrrhenian pirates. It seems worth asking if such associations, rather than marketing policy or exotic taste, may not account for Attic potters’ adoption of a few Etruscan shapes.”39 It seems unnecessary to speak of the explanation of the phenomena as an either-or proposition. Ceramics were an important component of an elaborate mechanism of exchange between Greece and Etruria in the Archaic period. It would hardly be surprising if Athenian potters developed a capability of manufacturing shapes that, they believed, had an Etruscan flavor. Interpreting the development of the shape and iconography of the kantharos in Athenian vase-painting as a mere reflection of trade patterns, however, is, as Seeberg implied, reductive. For the trade patterns are one raw material out of which myth can be created by Athenian ceramic artisans.

If the kantharos, associated with Etruria as a pottery shape, on the one hand, and with Dionysos iconographically, on the other, constitutes a link between Dionysos and Etruria, a link expressed in mythological discourse through the story of the god’s entanglement with the Tyrrhenian pirates, what might be the nature or meaning of the link? One possibility is suggested by the type of drinking vessel regularly held by Dionysos in Athenian vase-painting prior to, and then alongside, the god’s use of the kantharos. In many early representations of Dionysos, the god holds a drinking horn or keras. Originally manufactured out of a cow horn, the keras was the most primitive form of drinking vessel depicted in vase-painting. “It is said that the earliest humans drank from the horns of cattle. This is why Dionysos is represented growing horns” (Athenaios 476a). The association between the drinking horn and primitive life is analogical, for the shape calls to mind a time before humans worked in clay or metal, a time when people relied on found objects like the horns of animals for their drinking vessels. “In pictures, drinking-horns like kantharoi belong more to mythology; in life, they may have savoured of the rustic and the barbarian, as poetic allusions and the provenance of precious-metal facsimiles certainly suggest.” So Seeberg.40

If the drinking horn called to mind primitive life through its natural origins, how might the obviously artificial, elaborately wrought kantharos have done so? Its Etruscan associations may have evoked the idea of primitive life, because the so-called barbarian cultures were thought to preserve ways of life that the Greeks had long since left behind. The principle was articulated by Thucydides:

[A]ll the Hellenes used to carry arms because the places where they dwelt were unprotected, and intercourse with each other was unsafe; and in their everyday life they regularly went armed just as the Barbarians did. And the fact that [certain] districts of Hellas still retain this custom is an evidence that at one time similar modes of life prevailed everywhere. But the Athenians were among the very first to lay aside their arms and, adopting an easier mode of life, to change to more luxurious ways … [T]he Lacedaemonians were the first to bare their bodies and, after stripping openly, to anoint themselves with oil when they engaged in athletic exercise; for in early times, even in the Olympic games, the athletes wore girdles about their loins in the contests, and it is not many years since the practice has ceased. Indeed, even now among some of the Barbarians, especially those of Asia, where prizes for wrestling and boxing are offered, the contestants wear loin-cloths. And one could show that the early Hellenes had many other customs similar to those of the Barbarians of the present day.

Where does Hephaistos fit in the equation between the Etruscan origins of the kantharos, and Dionysiac mythology and ritual? Within mythological “social history” or speculation about primitive life, Hephaistos, like Dionysos, interacted with primitive populations. The indigenous people of Lemnos are called Sintians in Homeric epic, but elsewhere the Sintians are identified with the Pelasgians, the aboriginal population of Greece, and the Tyrrhenians (i.e., Etruscans), the ethnic group with which Dionysos is associated in the pirates myth.42 The association appears to be documented by a fascinating Athenian black-figure krater fragment attributed to Lydos and dating to 560 BC or perhaps even earlier (figure 42).43 The fragment depicts Hephaistos riding a sexually aroused donkey. The rider is identifiable as a god through the animal’s arousal, and as Hephaistos through his combination of short beard and short chiton. No god other than Dionysos or Hephaistos rides a donkey (aroused or not), and Dionysos does not wear a short chiton or (usually) have a short beard. The fragment presumably derives from a vase-painting of the return of Hephaistos, perhaps the earliest extant example in Athenian vase-painting after the François vase.

Figure 42: Rome, Museo del Foro 515366, black-figure krater fragment, attributed to Lydos, BAPD 9022287.

Two things about the fragment are relevant to the idea that Hephaistos was associated with Etruscan craftsmanship. One is that it depicts Hephaistos holding a beautiful and enormous carinated kantharos. This is the earliest known Athenian representation of the kantharos in a Dionysiac mythological context, and one of the earliest of all depictions of the kantharos. The image invites the question, did Hephaistos receive this magnificent kantharos from Dionysos when the wine god intoxicated the smith god and thus engineered his return to Olympos? Or did Dionysos receive his signature drinking vessel from the master craftsman Hephaistos in thanks for securing permanent recognition by the Olympians? In this pictorial narrative, the oversized, eye-catching kantharos, both drinking vessel and art work, is the perfect symbol of symbiosis between the powers or spheres represented by the two marginal gods, intoxication and artistry. It is a kind of visual metonymy for the krater on which the image was depicted, for the krater too unites the social practice of wine drinking and the labor of the potter and vase-painter. The second striking thing about the fragment is its findspot: it was discovered under the so-called lapis niger in the Comitium of Rome, in the Vulcanal or sanctuary of Vulcan. As many scholars have noted, the findspot cannot be a coincidence. It shows that the Etruscans and Romans had already equated the local fire- and metal-working god Vulcan with the Greek god of art and technology, Hephaistos.44

To return to the fragmentary krater in New York (figures 37–39), the narrative deployment of mid-sixth-century Athenian-style kraters within a representation of the return of Hephaistos makes an equation between the kind and quality of symposium-ware used in the circle of the legendary artisan god Hephaistos, and the sort of krater made and decorated by the contemporary ceramic artist(s) responsible for the fragmentary krater itself. The god of all artistry, famous in poetry for his metal vessels, seems to be at home with, if not personally responsible for, fine clay vases of a distinctly Athenian style. Like the S-O-S amphora on the François vase (figure 26), the depicted vases on the fragmentary krater in New York visually advance a claim that the contemporary vase-painter and potter are comparable to Hephaistos. The same claim appears to be advanced by the association of the kantharos with Dionysos via Hephaistos. And the association of the kantharos with “primitive” Etruscan culture is another means of characterizing the artisan and wine gods as socially marginal.

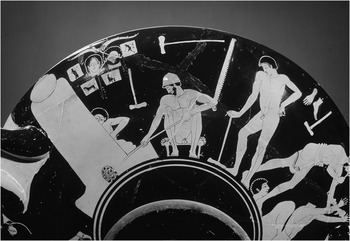

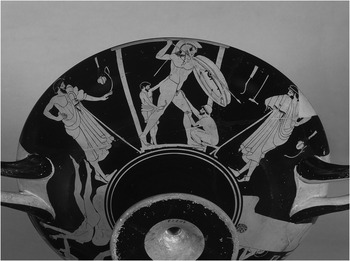

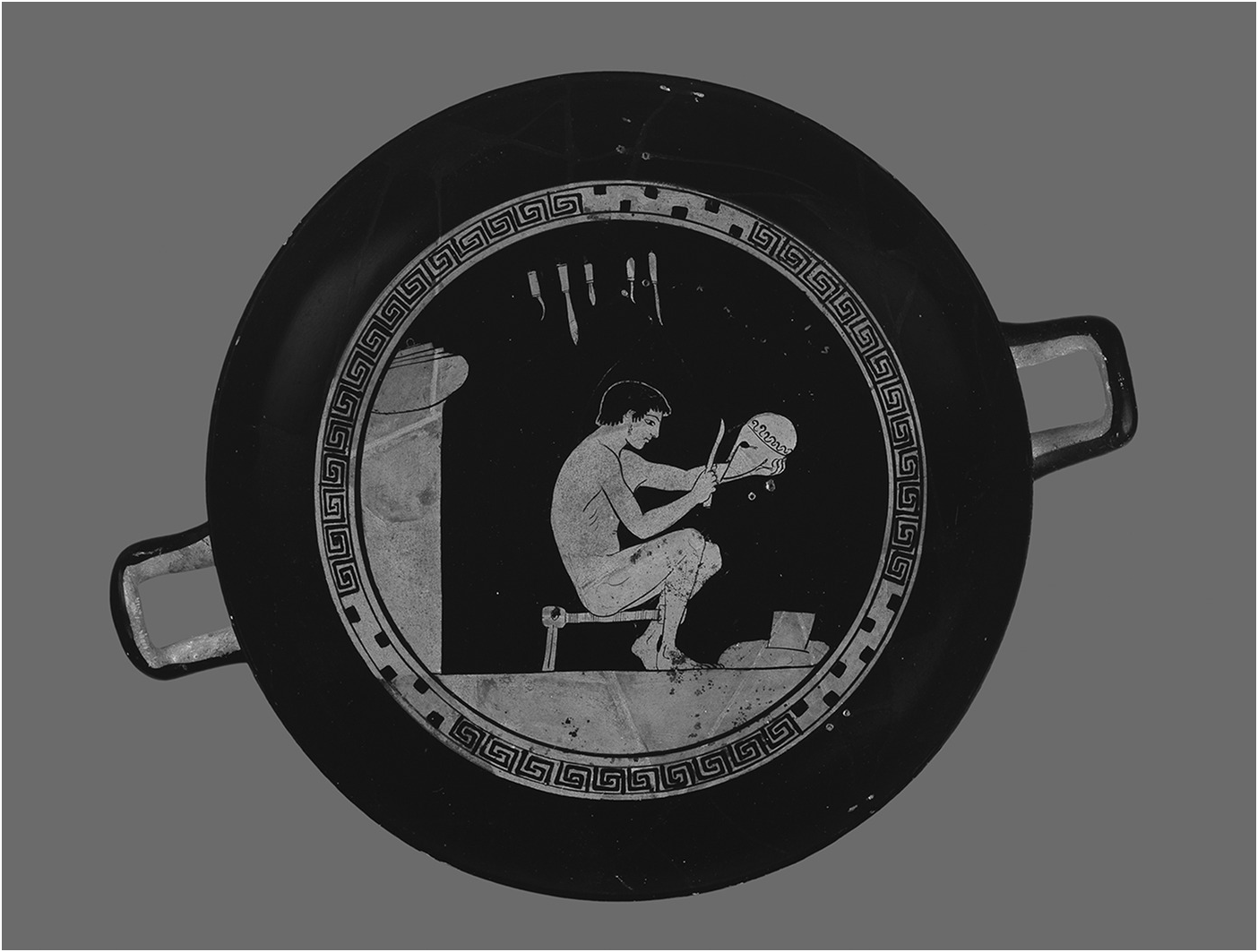

Hephaistos, Role Model for Sculptors, on the Name-Vase of the Foundry Painter

In the fragmentary remains of ancient Athenian art, there is one further work, like the François vase (plates XIV-XV) or fragmentary krater in New York (figures 37–39), that develops comparisons between the mythical deeds of the artisan god and contemporary artisanal production. Represented in the bowl of the late Archaic name-vase of the Foundry Painter (plate XVII) is a metalworker. He is seated in his workshop, finishing a helmet with a small hammer; waiting patiently is his customer, who already holds a spear and a fine shield decorated with stars. A pair of greaves, another hammer, and an anvil are included in the image.45 The female gender of the customer strongly suggests that she is Thetis, waiting to receive from Hephaistos a new set of armor for her short-lived son, after the first set was taken by Hektor. The story is the narrative frame for the famous description of the shield of Achilles in Book Eighteen of the Iliad, discussed in earlier chapters.46

XVII: Berlin, Antikensammlung, F2294, red-figure cup, ARV2 400,1, Foundry Painter, BAPD 204340.

On the exterior of the cup (figures 43–44), there is another representation of an artisans’ workshop, a bronze-sculpture foundry. In this case, however, the artisans appear to be contemporary, not mythical. Several steps in the creation of large-scale bronze statues are represented, from the melting of metal in a kiln, and the piecing together of a statue of an athlete, to the final polishing of an over-life-size statue of a warrior. The vase is among the most detailed of any representation of artisans in Greek art.47

Figure 43: Berlin, Antikensammlung, F2294, red-figure cup, ARV2 400,1, Foundry Painter, BAPD 204340.

Figure 44: Berlin, Antikensammlung, F2294, red-figure cup, ARV2 400,1, Foundry Painter, BAPD 204340.

Among the eight human figures represented in this image, there is a clear distinction in terms of hair, dress, and demeanor between six men who actually work with the tools and two men who watch. The hair of the figures engaged directly in the work is short; on the youngest member of the shop, it is cropped. The beards of the workmen are also trimmed. If they wear anything in their hair, it is a pilos or cap of the sort often seen, in late Archaic and Classical art, on the head of Hephaistos. The workmen are nude or, in two cases, wearing a short tunic or exōmis rolled up at the waist. Three of the men squat, low to the ground, on short stools, perhaps uncomfortably. The figure squatting behind the furnace directs his gaze in the direction of the viewer, perhaps giving up hope of sympathy from his coworkers and looking for it elsewhere.

The two men flanking the over-life-size statue of a warrior (figure 44), watching the workmen polish the bronze, are quite different. They wear fillets in their hair, and appear to have longer beards; they are draped in long mantles or himatia; they wear neatly tied shoes; there is a strigil and aryballos hanging next to each of the bystanders, whereas no other figure in the representation is outfitted with a kit for working out in a gymnasium. Most notably, they lean on their walking sticks in an ostentatiously leisurely manner. As if to emphasize a categorical difference between the bystanders and the workmen, the latter are drawn to a different scale from the former. The polishers are approximately half the height of the striding warrior. The differentiation in height allows the vase-painting to indicate that the bronze statue being polished is monumental, almost twice life size. But it also allows the vase-painter to differentiate the workmen from the mantled men leaning on sticks. For the latter are nearly as tall as the warrior. The differentiation in size is neither necessary compositionally nor unnoticeable. It signifies something. It is unlikely that the men leaning on sticks are meant to be taken as representations of statues simply because they are of the same height as the warrior. It is more likely that the differences in scale are a further means of differentiating systematically between the workmen and the watchers.

The connotations of the sort of attire, attributes, and attitudes possessed by the pair of spectators are relatively well understood.

The first is leisure, proclaimed by the unpinned himation just as it had been by the luxurious chiton. Warriors, like aristocrats, looked down on having to work for a living … [this] is the ideal reflected by the clothes. No-one could work in the big Athenian himation, any more than in the long chiton … The clothes enforce and proclaim leisure. In Veblen’s words, they communicate it conspicuously.48

The aryballos and strigil are associated with participation in athletics and the gymnasium. Those areas of Athenian cultural life had strong elite connotations. Although gymnasia were open to all citizens by the Classical period, slaves were prohibited. Lack of exercise is one of the critiques of artisanal work advanced by Xenophon: “the illiberal arts [banausikai], as they are called, are spoken against, and are, naturally enough, held in utter disdain in our states. For they spoil the bodies of the workmen and the foremen, forcing them to sit still and live indoors, and in some cases to spend the day at the fire.”49

Leaning on a stick appears to have denoted, first of all, attentive observation of some spectacle. The earliest occurrences of the pose in Greek art, in mid-sixth-century black-figure vase-painting, are representations of spectators watching wrestling.50 The pose is also employed in narrative art for a figure who is waiting for something to happen. On the exterior of Onesimos’ late Archaic cup in the Villa Giulia, Briseis is being removed from the tent of Achilles and escorted to Agamemnon.51 In the middle of the image, a girl is followed by two heralds–presumably Briseis, Talthybios, and Eurybates. To her right, a young man has leapt up in anger from a stool and pulls the sword from its scabbard. He must be Achilles, because a woman standing in front of him, trying to stop him, is labelled Thetis. Briseis is being led by a warrior labelled Patroklos. In front of Patroklos is a bearded man whose arms are extended to receive the girl, and who perhaps is Menelaos. Behind the bearded man, a smug, powerful, relaxed man leans on a stick. In pose, he seems especially well suited to be Agamemnon.52 The narrative background to the image assures us that Agamemnon is waiting for the girl to be delivered to him, and the image of a man leaning on his stick, like that of a figure leaning against a wall on a street corner in a film, corresponds visually to the idea of waiting. The figure of Agamemnon exemplifies, however, another connotation that the image of a man leaning on a stick seems sometimes to entail–power or authority.53

The relaxed air of the men leaning on sticks, whiling away the day watching other men work, is highlighted by the squatting position of some of the workmen. The position is motivated, in part at least, by their tasks. But the image of a figure squatting on the ground, particularly when the figure is shown frontally, so that the genitalia are visible, also appears to have connotations of social inferiority. The idea is suggested, for example, by the juxtaposition of two scenes of a potter’s workshop on a lip cup in Karlsruhe dating to the third quarter of the sixth century (figures 45–46).54 On one side of the cup, a potter shapes a cylinder of clay into a vase on a potter’s wheel. The wheel is turned by a boy, buck naked like the potter. The boy sits on a low block, his body oriented frontally toward the viewer, his legs spread, genitalia prominent. This exact pose is not necessitated by the depicted action, for the wheel-turner could have been shown in profile view. On the other side of the cup, the manufacture of the kylix is complete; it is a Little Master cup, in shape similar to the vase on which its picture is painted. The potter, who is seated on a stool before the wheel, is perhaps applying glaze to the foot of the cup. Once again, the potter is nude. Standing before him, in the place where the boy sat and turned the wheel, is a heavily draped male figure, with one hand extended. He is the one figure in either image on the cup who is not directly involved in the production of the vase, yet his attention suggests that he is interested in it. Perhaps he is contemplating making a purchase of the depicted cup for use at his next symposium. Turn the cup around and around: the visible contrast in posture and dress between the pot-purchaser and the wheel-turner seems deliberate and pointed. Presumably, the differences are rooted in the socioeconomic differences between working in a pottery shop and participating in sympotic culture.55

Figure 45: Karlsruhe, Badisches Landesmuseum, 67.90, black-figure cup, BAPD 355, manner of the Centaur Painter.

Figure 46: Karlsruhe, Badisches Landesmuseum, 67.90, black-figure cup, BAPD 355, manner of the Centaur Painter.

The Well-Heeled Artisan and the Antiphon Painter

The differences among the male figures on the exterior of the name-vase of the Foundry Painter (figures 43–44) have been interpreted in essentially two ways, and the implications of the rival interpretations are significant for the understanding of the self-representation of the artist in Greek art. The pair of figures leaning on sticks, watching the work, are sometimes identified as the owners of the workshop–master sculptors or bronze-casters. If they are artisans, their dress, pose, and accessories suggest that they are financially successful men. They have the wherewithal to employ assistants, who allow them the leisure to work up a sweat at the gymnasium. That interpretation of the vase-painting, in turn, has been advanced in support of the theory that wealth accumulated through work allowed men to participate in all the activities traditionally associated with the social elite. This line of argumentation sometimes leads to the conclusion that the vase-painter Smikros really lived like he depicted himself (plate I).

In support of the identification of the relaxed, mantled, gym-going men as financially successful artisans, Burkhart Fehr compared a roughly contemporary cup in Boston (plate XVIII). The cup is attributed to the Antiphon Painter, or an artist working in his manner, and depicts a young vase-painter at work. In a sense, this is a self-portrait. The vase-painter is applying glaze with a fine brush to a kylix similar in shape to the vase that bears his image.56 Of particular significance are the young artist’s accouterments. He sits on a well-made wooden chair. He is dressed in a long himation, which is allowed to gather around his waist. Beside him is a walking stick, strigil, and aryballos. He may be engaged in skilled labor, but his accouterments suggest that he has adequate leisure time to work out in the gymnasium or stroll around town in a komos.

XVIII: Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, 01.8073, Henry Lillie Pierce Fund, red-figure cup, ARV2 342,19, manner of the Antiphon Painter, ca. 480 BC. BAPD 203543.

Fehr took the representation on the cup by the Antiphon Painter to be a primary document. Implicitly, the vase-painting is as probative as the testimonium of Xenophon, that skilled labor is incompatible with the cultivation of a healthy masculine physique, because it requires artisans to spend long hours seated indoors and it leaves them no time for the gymnasium. The pictorial representation demonstrates, he argued, that craftsmen possessed walking sticks and gym kits, and thus that the mantled men on the name-vase of the Foundry Painter (figure 44) are as likely to be sculptors as anybody else.

It seems obvious, therefore, that the vase-painters did not intend to indicate any striking difference in social rank between the workshop visitors leaning on their sticks and the men working, as has sometimes been suggested … If we attempt to verbalize what is narrated in these scenes, it may be expressed in the following way: after his work is finished, the craftsman can clean and anoint his body, … put on his citizen’s himation, go where he likes … watch whatever he is interested in as he leans on his stick, such as other men working or athletic activities.57

The argument would be persuasive if it were certain that the vase-paintings by the Antiphon or Foundry Painters represented the material and social realities of the lives of craftsmen in a one-to-one manner, so that every pictorial element had its counterpart in the real lives of artisans. In the history of art, some drawings undoubtedly represent visible reality in just such an exacting way–anatomical drawings, for example. Not every drawing of the human body, however, is a reliable guide to a surgeon. The history of artistic representation of mythical creatures shows that there are extraordinarily plausible images of the bodies of nonexistent beings. How to determine whether a drawing of the body is trustworthy, in the absence of prior direct visual experience of the body or part in question, depends less on the internal coherence or plausibility of the image than on its genre–on the conventions that govern the creation and inspection of the drawing. “If any image of the Renaissance could illustrate any text whatsoever, if a beautiful woman holding a child could not be presumed to represent the Virgin and the Christ child, but might illustrate any novel or story in which a child is born, or indeed any textbook about child-rearing, pictures could never be interpreted.”58

For the identification of the expectations that attended the creation and reception of the cup in Boston (plate XVIII), there are two sources of information. One is other vase-paintings. Thanks to happy accidents of survival, it is possible to compare the imagery on the cup in Boston to other vase-paintings, similar in composition or subject, by the same artist or circle of painters. The comparison shows that the Antiphon Painter is capable of creating scenes of “daily life” that are contrary to fact. A contemporary cup in the Ashmolean Museum also attributed to the Antiphon Painter depicts a craftsman in a related field, a metalworker (figure 47).59 In contrast to the vase-painter depicted on the cup in Boston, the metalworker sits on an uncomfortably low, utilitarian stool. He wears no clothing at all. His accouterments–a furnace, cauldron, anvil, and metal files–belong exclusively to the manufacturing district of the city. By comparison with the depicted metalworker, the fictive vase-painter appears to have a place in two social worlds, that of skilled labor and the world of leisure. A third cup by the Antiphon Painter or in his manner depicts yet another craftsman (figure 48).60 This cup depicts a sculptor or stone-cutter, carving the flutes into a column. He sits on a low stool. Like the two other craftsmen, the stone-cutter is outfitted with an accessory that contributes to his characterization. This craftsman’s attribute is a skin filled with wine, because this craftsman, as revealed by his ear, is a silen. The cup is important because it assures us that craftsmen depicted by the Antiphon Painter (or artists working in his manner) do not always or necessarily have exact counterparts in the real world. The comparison of the three cups is instructive, because it suggests that vase-paintings themselves, in comparison with each other, provide a point of view or commentary on their own visual propositions. It is unsafe to assume that they all may be taken at face value.

Figure 47: Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, G267 (V518), red-figure cup, ARV2 336,22, Antiphon Painter, BAPD 203459.

Figure 48: Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, 62.613, gift in memory of Arthur Fairbanks, red-figure cup, ARV2 1701,19bis, Antiphon Painter (or manner of), ca. 475 BC. BAPD 275647.

The second source of information on the expectations surrounding the vase-painting and its reception is the function of the cup (plate XVIII). The shape of this vase, a drinking cup, suggests that it was intended for use in symposia. In a sympotic context, this depiction of a vase-painter seems capable of eliciting a complex reaction. On the one hand, in the young vase-painter’s accessories, the symposiast-beholder may very well recognize the sort of athletic or leisure gear that he himself possessed. On the other hand, there is reason to believe that the occupation of the depicted figure–vase-painting–is not an occupation closely associated with participation in sympotic life. When Plato describes an impossible society, what he imagines is similar to what is depicted on this cup–potters reclining on couches, drinking toasts and feasting, with their potting wheels nearby (Plato, Republic 420e-421a). The vase-painting presents a puzzle to be worked out, a contradiction between those aspects of the appearance and behavior of a cup-painter that accord with experience, and those that contradict it. The vase-painting would invite this sort of interpretation even if it were the case historically that, from time to time, a vase-painter might have been seen with a stick and gym kit.

The picture invites the kind of inquiry we are engaged in now, because the image dovetails with stereotypes that go all the way back to the characterization of the ur-artisan Hephaistos in epic poetry. The cup-painting compactly articulates in non-narrative form the question posed on the François vase through the juxtaposition of images of Hephaistos in the wedding of Thetis and the return of Hephaistos (figures 25, 27). Is he or is he not a member of the elite? Like Hephaistos, the Antiphon Painter (whoever he is) did not passively allow his elite society to answer this question for him, but utilized the means available to him as an artist in the Odyssean tradition to address the issue–indirection and fiction. He may not have been able to secure an invitation to the party at which his cup was utilized, but through the creation of the puzzling pictorial proposition of the vase-painter who hangs with well-heeled men, the Antiphon Painter made his presence felt.

Sculptors Emulating Hephaistos on the Foundry Cup

To return to the name-vase of the Foundry Painter (plate XVII, figures 43–44), the alternative interpretation of the mantled men leaning on sticks–that they represent elite customers or potential customers–is not only well supported by the iconography of the mantled stick-man, but also strongly suggested by the compositional structure of the cup itself. The two men, leaning on sticks, observing the completion of work on the statue, are the counterparts, within the world of the bronze foundry, of the female figure of Thetis in Hephaistos’ workshop in the tondo of the cup. Compositionally, Thetis places weight on a stick-like spear and un-weights one foot, in a pose suggestive of leisurely or patiently waiting, just like the men on the exterior of the cup. Semantically, the pictorial function of Thetis is established by the narrative association between the scene unfolding in the tondo and the story of the creation of the armor of Achilles. She is the customer, waiting in the workshop of the divine metalworker for the completion of her order. The pictorial narrative unfolding in the tondo suggests that the male figures, observing the completion of the statue on the exterior of the cup, are also customers.61

This pot was painted at a time when the three surfaces of a kylix were sometimes painted with representations related in theme.62 Homer Thompson argued that the links between the interior and exterior pictures on the name-vase of the Foundry Painter went beyond the common theme of bronze-workers in their workshops, to embrace the story of Achilles. The over-life-size statue of a young, long-haired, formidable warrior he identified as a statue of Achilles in battle; the bronze statue of a runner being pieced together on the other side of the cup Thompson identified as a statue of swift-footed Achilles. “In the floor medallion the divine smith Hephaistos honors Achilles with his craftsmanship. On the outside of the cup mortal artists prepare monuments to the glory of the same hero.”63 Although the identification of the partly assembled bronze athletic statue as Achilles would be unparalleled, the identification of the martial statue as Achilles is supported by several contemporary works of art.64 The twice-life-size scale of the bronze, and the long, uncut locks of hair, suggest that the bronze figure represents a hero or a god. On this cleverly designed cup, there is a subtle play between the shield, helmet, and spear manufactured by the god Hephaistos for the hero Achilles, and the shield, helmet, and spear manufactured by the bronze sculptors for their monumental representation of the hero. The presence of the hero is evoked in the tondo through pictorial narrative and made palpably real in the bronze statue on the exterior, but the hero himself is nowhere to be seen apart from those works of art. That is a powerful statement about the indispensable mediating role played by art–and the artisan–in the perpetuation of the kleos or fame of the hero.

The name-vase of the Foundry Painter, like the François vase, though more directly and explicitly, invites comparison between the technical work entailed in contemporary craftsmanship and the legendary skill of the god Hephaistos. It also maintains and arguably highlights the distinctions in social status or way of life between the makers and consumers of artisanal products. At the same time, it expresses, pictorially, the subtle means by which Hephaistos confronts social hierarchy. The most striking feature about the reverse of the cup (figure 44), compositionally, is the disparity in scale between the clients and the sculptors. On one level, the disparity articulates or corresponds to the differentiation or distinction in terms of wealth, occupation, and social milieu, between bigwig patrons and insignificant craftsmen. But the disparity in scale also means that the clients are drawn nearly to the same scale as the bronze statue of the hero. On one level, again, the disparity in size between the hero and sculptors serves to establish that it is not a real person like the polishers but a (twice-life-size) statue. At the same time, the similarities in scale, and perhaps also the similarities in pose, invite comparison between the clients and the bronze statue. The clients do not come off so well in the comparison: they are slightly shorter, no longer in the prime of youth, afraid perhaps to go into action in the nude, with tender feet. The clients need to go to the gym every day to maintain their physique, whereas the magnificent image of the hero, once it is polished, will never lose its muscle tone or military vigor. The clients may come across as more fortunate in their possessions and way of life than the artisans who are laboring to complete the statues in this vase-painting, but the artisans turn the tables on the clients, because the product of their labor is finer and more fortunate than the clients could ever hope to be. Like Hephaistos, the greatness of the artisans lies not in themselves but in the products of their ingenuity.