Food security refers to the ability of individuals, households and communities to acquire appropriate and nutritious food on a regular and reliable basis using socially acceptable means. It is determined by both the food supply and people's ability to access and use food. Food insecurity refers to any of the following: (i) not having sufficient food; (ii) experiencing hunger as a result of running out of food; (iii) eating a poor-quality diet as a result of limited food options and access; (iv) anxiety about acquiring food; or (v) having to rely on food relief( Reference Rychetnik, Webb and Story 1 ). Food security is an important public health issue both globally and locally. As food insecurity impacts on nutritional intake it can contribute to a number of diet-related diseases. Chronic disease risk and incidence, adult obesity (especially in women), HIV infection, diminished cognitive performance, academic achievement and behaviour problems in children have all been associated with food insecurity in developed countries( Reference Sullivan, Clark and Pallin 2 – Reference Taras 9 ). In South Australia an average of 5·6 % of survey respondents aged over 16 years reported to ‘have run out of food and could not afford to buy more’ between July 2002 and December 2006( Reference Carter and Taylor 10 ). However, the real number experiencing food insecurity is likely to be more as individuals of highest risk such as homeless people and people with mental health, drug and alcohol problems can be missed by population health surveys( Reference Booth and Smith 11 ). Despite the recognition that food security is an important public health issue, there remains a gap in the evidence base both internationally and locally on the most effective policy options to improve it. With the move towards evidence-based policy, public health policy makers may turn to systematic reviews of the literature to uncover sound evidence on what works and which types of solutions provide the best value for money. However, this approach often overlooks the impact of local context on the success of interventions. Pawson proposes a ‘realist’ approach to the synthesis of evidence to overcome this challenge. This methodology considers the local contexts of interventions to uncover what types of strategies will work for which people in what kinds of settings or ‘what works for whom in what circumstances’( Reference Pawson 12 ). With the lack of evidence and evaluation on what specific policy options should be implemented to address food insecurity generally, and in South Australia particularly, policy makers need to be flexible in types of evidence they use. Target populations and stakeholders provide their own forms of evidence (knowledge, experience, ideas and opinions) that interact with research evidence( Reference Hector, Hyde and Worgan 13 ). Consultation with these groups can provide insight into the feasibility of implementing certain policy options and strategies and thus increase their effectiveness( Reference Blas, Gilson and Kelly 14 , Reference Popay and Williams 15 ).

The research presented in the current paper explores key stakeholders’ perceptions on food security within South Australia and forms part of a larger study with the overarching aim to identify local evidence-based policy options for the South Australian state government to improve food security. The findings presented here relate directly to the research question ‘what do key stakeholders think are the realistic policy options to improve food security within South Australia?’ For the purpose of the current research the term ‘key stakeholders’ refers to stakeholders who have potential to impact food security through changing the food supply or through influencing social and economic determinants of health and thereby people's access to food. ‘Realistic policy options’ refer to interventions and strategies that have potential to improve food security and are deemed feasible within the context (considering political, economic, social and cultural factors) of South Australia.

Method

The current research takes a constructionist perspective with the underlying assumption that the success of policy solutions is dependent on the local context in which they are to be implemented. It is based on underlying principles of grounded theory methodology, where outcomes of the research are fed back into the research as it progresses and in doing so help shape and form the research design( Reference Grey 16 ). Before gathering and analysing stakeholders’ views on food security a systematic literature review was conducted for the past decade to uncover various ways food security is spoken about within the academic literature and emerging themes on determinants and potential policy solutions. Using a grounded theory approach the literature review findings helped make sense of the interview findings as they emerged, rather than the literature determining a set of evidence-based policy options which participants were asked to prioritise or choose from. This helped expand vision rather than constrict it and allowed for local evidence (knowledge, experience, ideas and opinions of key stakeholders) to be truly valued through influencing the study design( Reference Pawson 12 ). Similarly, participants were asked to identify other potential stakeholders for interview throughout the study. This snowball sampling was chosen so that study participants could use their local knowledge to help shape research design. As the project progressed findings from earlier interviews were fed into subsequent interviews to test the acceptability of proposed solutions. By using this approach data from earlier interviews not only influenced who was interviewed at a later stage but also the types of questions they were asked. Any new emerging themes and stakeholders were noted as the study progressed. The recruitment of participants was concluded once no new stakeholders or themes emerged (had reached a point of saturation).

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with twenty-four key stakeholders currently involved in food security or with the potential to improve food security within South Australia. Ethics approval was sought and obtained from Flinders University social and behaviour research ethics committee. Participants were sent a discussion paper on food security which formed the basis for key questions asked during the semi-structured interviews. Voice recordings of interviews were transcribed verbatim to allow for detailed analysis( Reference Patton 17 ). Interview transcripts were then rechecked against voice recordings by the principal researcher to ensure accuracy. Participants were emailed their interview transcripts and offered the opportunity to make any amendments, a step that helped to further enhance the validity of the research method( Reference Perry 18 ).

Prior to analysis audio files were listened to and interview transcripts were read and re-read to allow for immersion in the data, a method employed to enhance analysis( Reference Green, Willis and Hughes 19 ). Following this immersion, data analysis was conducted first to identify emerging policy options for food security expressed by key stakeholders and second to compare and contrast solutions provided with those found within the academic literature. Data were coded into common themes and proposed solutions by stakeholders were examined against literature arising from the systematic literature review and against each other to remove any inconsistencies. Some solutions to food security offered by stakeholders did not provide a defined role for state government, so these were either adapted to clearly outline the role for government or if no role could be identified they were left out. To further contextualise and validate data a collation of main emerging themes and policy options proposed was presented back to participants in a written document. Stakeholders were given the opportunity to provide any further comments or thoughts they had after reading and reflecting on the data. This process of verifying the research findings helped contribute to the study's rigour and reliability( Reference Morse, Barret and Mayan 20 ).

Results

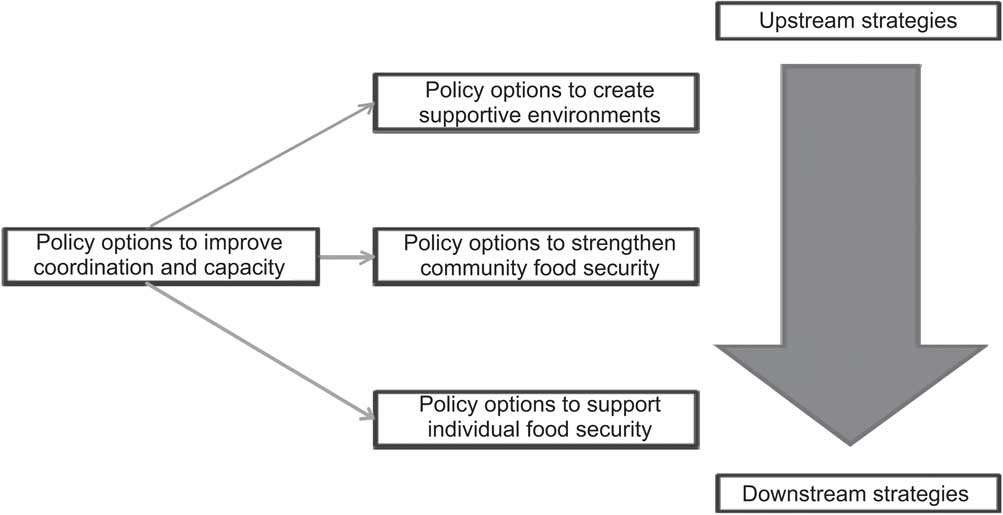

Proposed policy options arising from the current research have been organised into four categories of action: (i) policy to create supportive environments; (ii) policy to strengthen community action; (iii) policy to support individual food security; and (iv) policy to improve coordination and capacity for food security. This is consistent with thinking about food security from a macro (supportive environments), meso (community action) and micro (individual) level( Reference Naidoo and Wills 21 ). It also shows consistency with McCullum's three stages of food systems redesign for food security by considering initial food systems change (individual), food systems in transition (community) and food systems redesign for sustainability (structural/environment changes)( Reference McCullum, Desjardins and Kraak 22 ). Figure 1 provides an overview of these four categories into which policy options are organised and illustrates how policy options move from those taking an upstream approach through to those taking a more downstream approach. By organising policy options in this way, policy makers can easily identify which aspect of food security they are trying to improve and the type of policy tool being used.

Fig. 1 Policy options categorised as upstream to downstream public health action

Policy options that met strong resistance from stakeholders were removed while those deemed acceptable by the majority were included. Solutions deemed acceptable (given the breadth of stakeholder representation) are policy options that will allow for easier implementation and therefore are the most realistic. It should be highlighted that the concept of realistic is not necessarily the same as the concept of effective. For example, a very effective policy option could be price manipulation of healthy and unhealthy foods by tax reform. However, this solution met resistance by a number of key stakeholders and policy makers, raising questions about how realistic the solution is in this given context.

Table 1 presents forty-four identified policy options arising from the research under the four identified categories of action in Fig. 1. Within Table 1 policy options are further identified as actions relating to: policy development and implementation (Policy), advocacy action (Advocacy), education programmes (Education), new research (Research), organisational change (Org Dev), increasing workforce capacity (Capacity) and direct government investment and funding for new programmes or infrastructure (Funding). Furthermore policy options have been classified into those addressing the following food security aspects: supply of food (Supply), access to food (Access) and overarching systems supports (Support).

Table 1 Local evidenced-based policy options to improve food security in South Australia

Discussion

The present research reveals how gathering of local evidence can help expand understanding on an issue by providing a range of context-specific and detailed policy solutions. For example, the proposal for state government to invest in infrastructure (such as roads) to ensure food moves from farm gate to consumer in the smoothest and fastest way relates directly to the South Australian context and the problem of large trucks having to take indirect routes due to poor roads or bridges that are too low to pass under. Similarly, the recommendation to support remote Indigenous community stores to create preferred-provider lists for food purchasing in order to keep food costs down (through resultant increased buying power and reduced transportation costs) arises from stakeholders’ in-depth knowledge of how community stores currently operate and the barriers they face to providing fresh affordable food.

In the study design literature was not used to influence or limit stakeholder responses. Rather than presenting participants with the evidence base around what can be done to improve food security and asking them to comment on or pick suitable solutions, stakeholders were asked to draw on their own knowledge and experience to offer potential strategies. This acknowledges and values local expert knowledge and resulted in additional ideas and solutions being presented by stakeholders than were found within the literature. However, the influence of academic literature on stakeholders’ knowledge and ideas was evident as many of the proposed solutions were also found within the literature. Research evidence often diffuses through multiple channels, such as scientific and professional journals, the mass media and conversations between policy makers and researchers, and contributes to a series of concepts, generalisations and ideas that impact on the types of solutions offered( Reference Short 23 ). This is evident in the proposed solutions to work with industry to set targets for certain nutrients (salt, saturated fat, energy) and to develop front-of-pack nutrition labelling. Both of these strategies are currently being employed in the UK in their public health nutrition efforts to improve the food supply and change consumer behaviours( 24 , 25 ).

The method of consultation employed in the present study has a number of advantages. Stakeholders could speak freely during interviews and each had equal opportunity and time to present their views on food security. Discussions were not dominated by a vocal few, as can often occur in focus groups or meetings where there are differential levels of power between participants due to various feelings of confidence, knowledge and experience. Furthermore, stakeholder views were not influenced or persuaded by other participants’ views. However this could also be considered a disadvantage as there was no opportunity for stakeholders to discuss concepts and come to agreement on main themes and policy options. Proposed solutions emerging from interviews were raised in subsequent stakeholder interviews to further understand how these solutions could be practically implemented, allowing for further contextualisation.

A limitation of the project was representativeness of participants. Half of the project participants worked either directly or indirectly on issues of food security for a range of local government, community health and peak non-government organisations. The remainder of participants worked in health, planning and social policy, or were involved in the food supply across food retailing, food transport, farming and food production sectors. There was a general under-representation of private industry stakeholders across all areas of the food supply and gaps in stakeholders directly involved in public housing and employment. Despite these gaps, use of consultation within the present research effectively captured a diverse range of views from relevant stakeholders.

The process enabled new stakeholders to be identified, information and views to be exchanged and proposed policy solutions to be contextualised, illustrating how gathering local evidence can help expand understanding on an issue. While the research's intent was to develop policy options specifically for the South Australian government and context, many of the policy options are relevant for other settings and indeed some of them have been used in other settings. Furthermore, the principles of the process used to generate these policy options are applicable to other public health problems and other contexts.

Acknowledgements

There was no funding received for this research and the authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. The research formed part of the principal author's (A.B.) Dr.PH thesis, which the second author (J.C.) supervised. A.B. conducted the research, including gaining ethics approval and conducting interviews, literature reviews and data analysis. J.C. supervised this process and reviewed the written article, adding comments and suggestions. The authors acknowledge and thank the key stakeholders interviewed for their time and ideas.