1 Introduction

This Element is intended for language teachers, future language teachers, and teacher trainers. Its recommendations for using technology are based on research and the text will refer to research findings frequently. It will also make the claim that research and its theoretical basis are important for language teaching. However, it is mainly concerned with pedagogy and ways to make online teaching successful.

This first section will start with suggestions on how this Element can be used and how it can be useful. I will then talk about the style used here and in the other parts of the Element, and describe some of the purposes of its features, such as tasks and examples. This is followed by an outlook of all chapters. The Introduction will finish with some explanations and definitions. A glossary of terms used in this Element can be found at the end.

1.1 Using This Element

There are different ways to access this Element – different pathways through the material.

It can work as a thorough grounding for teacher trainees and people interested in the foundations of online language learning. This pathway starts with the theoretical approach, with a discussion of various learning theories and how they fit with language learning and with online language teaching. Readers taking this path might want to skip the practical tasks at the end of each section, and quickly skim the more practice-focussed Section 4.

For practitioners concerned with using technology successfully and taking their language teaching online, the pathway focusses on practical and reflective tasks, on different ways of teaching languages and how they can be successfully adapted to fit an online or blended teaching environment. If you are more interested in practical changes, you may want to skip the theoretical Section 2 at first, and maybe come back to it later. You can start with Section 3, which focusses on pedagogy, and make sure that you engage with all the tasks suggested for practical training.

For the very experienced language teacher with a firm grounding in theory and pedagogy, the refresher approach may be most suitable. This starts with recommendations and examples for online teaching and practising the art of online communication in Section 4. Occasionally, when needed, readers taking this pathway can return to theoretical or pedagogic aspects specific to online language teaching.

The Element can also be employed in language teacher training courses using a flipped pedagogy. The main text of the chapters can be set as preparatory reading, the tasks as homework, and the results of the tasks shared in presentations and discussions in class time.

Finally, if you still need to be convinced that online language teaching works, and that it is here to stay, you could start reading the penultimate section with examples from recent research into online language teaching and learning, and how this research confirms success in a teaching environment that may become more of the norm for us all in the future.

1.2 The Style

To justify the different styles in this Element, it is necessary to introduce my own approach to teaching and research. I am a language teacher and teacher trainer, and as such I take a personal approach, trying to create a personal link to my students and to communicate with learners and colleagues in a personal style. In my view, this makes learning more relevant and more fun. As a distance language teacher, I use this style not only in face-to-face communication but also when writing course materials, books, web pages, tasks, and task instructions. Those parts of this Element, where I write as a teacher or trainer, are written in a teaching voice, directly addressing you, the reader.

On the other hand, I am also a researcher, trained in the continental style of written argumentation and the English academic style of clarity and sequencing. When I write about my own or other people’s research, I tend to use an impersonal style; trying to present facts and findings succinctly and without recourse to rhetoric or persuasion. For researchers, it is our way of saving time and coming to the point without diversion, and it is more convincing to fellow researchers than a more entertaining or engaging way of writing.

1.3 The Structure

Each section provides a brief introductory overview, dips into theoretical aspects, and refers to research where appropriate. Apart from Section 2, all the chapters also provide examples of online teaching or suggestions for online tasks or strategies. References are provided to allow in-depth follow-up for some of the suggestions.

To deepen your understanding and allow you to experience the principles discussed immediately, every section will contain suggestions for tasks, such as reflections and additional practice. This will make it easier to employ the Element as a workbook or foundation text for a teacher training module; it will also allow independent working through the Element for experienced teachers aiming to upskill. Not all tasks will be suitable for all types of teachers, and sometimes there are alternative suggestions. Where the task, reflection, or additional practice does not suit or is not possible, it can be skipped without losing the thread of the text. If you like the practice-oriented, active learning approach, you can repeat tasks and revisit the notes you have taken on your reflections at a later stage of reading.

1.4 Overview of Sections

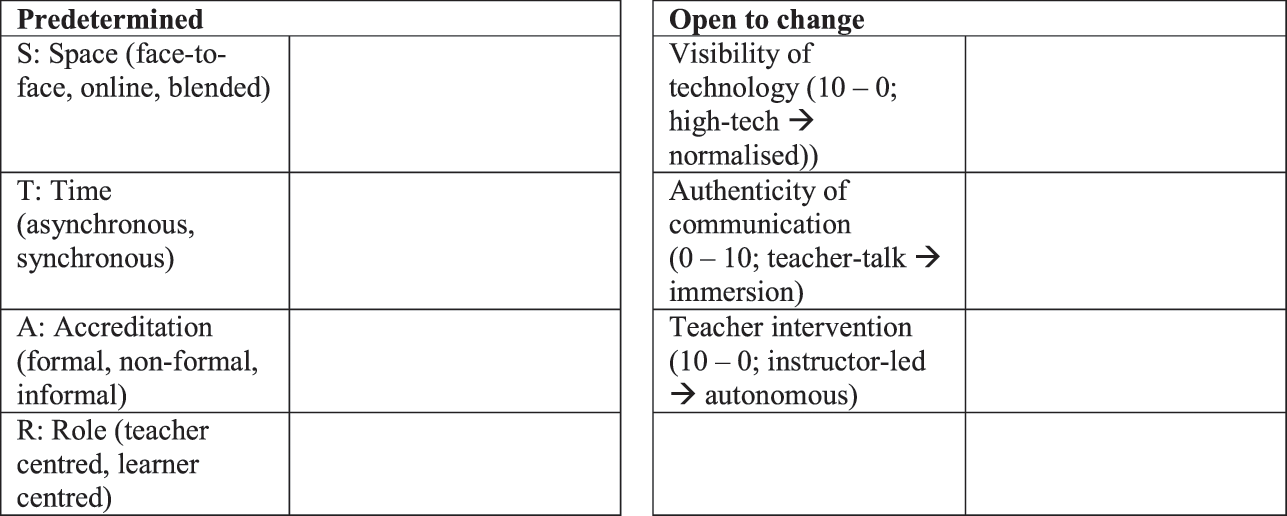

This introductory section provides a description of online language learning and teaching, differentiates online from offline teaching, and sketches ways of blending the offline and online elements of language teaching. It also introduces a framework that helps to describe the given teaching situation (STAR).

Section 2 goes to the foundations of our understanding and supports the claim that language teachers need to reflect on their epistemological stance to make the best choices for their online language teaching. It also sketches some learning theories and links our understanding of how humans communicate to the implications of our views on reality and knowledge.

Section 3 focusses on pedagogies and ways to enhance your online teaching by choosing the approach that best fits the given situation. This is grounded in a brief historical overview of the development of language teaching approaches, specifically those concerned with technology-enhanced and online teaching.

Section 4 then points out various options for teachers to shift their practice along three dimensions: the visibility or centrality of technology, the authenticity of communication, and the dominance or the interventions of the teacher. This is illustrated with some examples.

Section 5 shows how we can find out more about how online language teaching works. It provides examples of research projects that prove or disprove our assumptions of online learning. This section also reconfirms how keeping abreast of current research can be beneficial for language teaching, especially in technology-enhanced teaching, an area that changes rapidly and often with unexpected outcomes.

Section 6 provides an outlook into the future of language teaching and prepares us for future challenges. This preparation comes in the form of practical tips for language teachers, and also looks at the future of the entire profession, reconsidering what qualities will make the teaching and learning of languages still desirable in the future, when we will live with technologies that can take over practical functions such as translation or interpreting.

1.5 Online, Technology-Enhanced, or Computer-Assisted?

Nowadays, the word ‘technology’ is often used to refer to digital tools and technologies in general. This shows how much information and communication technology (ICT) has become a mainstay of our lives. Before starting to talk about the practice or theory of online language teaching, it might therefore be worth considering the delineations of the field covered here. My specialist research area is called CALL (computer-assisted language learning), which was originally defined by the use of a computer, most often in a classroom or computer room. This definition has long been superseded due to a change in technology and technology use. Tools have become less central, and for definitions of a research context, tools are no longer the main consideration. Employing ICT has also become an everyday practice for teachers. Definitions of the teaching context based on either technology or computer use have thus become almost meaningless. Instead, important criteria to describe language teaching practices include:

Space: Is the teaching context purely face-to-face or fully online or is it blended (i.e., part of the teaching takes place in physical proximity and part at a distance)?

Time: Is the communication asynchronous (e.g., email, blog) or synchronous (e.g., Skype, video-conferencing), or a mix of both?

Accreditation: Is the educational setting formal, informal, non-formal, or does learning happen incidentally?

Role: Is the teacher the focus of the classroom or is the learner in the lead?

As a teacher you may feel that you don’t have much choice about these STAR (Space, Time, Accreditation, Role) factors. The space and time of your classes are decided by the educational institution, as are assessment and accreditation. There might even be an expectation about the ‘proper’ role of a teacher, often influenced by national or sector-specific standards. The STAR delineations can help to describe your teaching situation and to identify where it is possible to achieve change or where you are constrained by the given situation.

1.6 Conceptual Not Technical

Throughout this Element, I will continue to refer to CALL as research area. I will also use online learning and online teaching as pedagogical practices. I will try and avoid the term ‘virtual’ to characterise learning in online environments because the term implies that communication in virtual spaces may have less reality than communication taking place in physical presence. When I talk about online learning, I refer to a context where the majority of teaching and learning takes place online at a distance (i.e., students are not in a classroom where they use tools to go online while at the same time being in the physical presence of other learners and a teacher). Online teaching also implies the deliberate, planned, and pedagogically sound use of online learning environments and tasks. In contrast to this, I would call a face-to-face classroom where some tasks are completed with the occasional use of digital tools, such as tablets or smartphones, a technology-enhanced learning environment.

Blended learning is a deliberate, planned mix of online (distance) and face-to-face teaching and learning. When I use the term here, I am assuming that a considerable part of the teaching takes place online; and – again – that the move is planned and supported with appropriate pedagogy.

The shift from CALL to online learning is not just a question of terminology but a conceptual shift. Online communication takes away some of the aspects of face-to-face communication (just think about sensory impressions, such as smells or the joint realisation of space and distance) and it adds other aspects (e.g., the persistence of digital traces and the option of recordings). Throughout the Element, reasons why online language teaching is different from face-to-face teaching and from teaching other subjects online will be presented. These reasons go beyond the obvious (i.e., the use of technology to facilitate communication between learners and teachers). In short, the online medium changes the way the teacher can help their learners to make meaning of the language they are learning and – as I will argue – this requires a change in pedagogy.

1.7 Task

Reflecting on your needs and your previous experience, choose an appropriate pathway through the Element. To do this, you can either take a rational approach, writing down your goals and aims and matching those to section headings and the description given in the Introduction. Then select the pathway and note down where you will start reading or working through the Element.

You can also take a more imaginative approach to selecting your path by following the dream walk in the text that follows. Some people prefer this kind of mental exercise with closed eyes following a guiding voice, so there is a recorded version of this task available (Sound 1).

Sound 1 Audio file available at www.cambridge.org/stickler.

Doodle or imagine a path. In your mind start walking along this path, focus on the forward direction it takes you, but also allow impressions from the environment to enter your imagined walk. You can see plants or vistas to the side, hear rustling leaves or a motorway, smell flowers or a deli, and feel the movement of air and the ground under your feet. Keep walking. In the distance you see the end of the path. Allow yourself a pause and think about what you would like to find at the end of this path.

Can you match your desired goal with any of the following descriptions? Then you just follow the recommended path.

a) If you want to find knowledge or understanding, follow the recommended pathway for the theoretical or foundational approach. Keep going and work systematically through the materials, taking notes and following up additional information with outside links.

b) If you want to find confidence and security, focus on the practical pathway, and do as many tasks as you can fit in. Take regular account of your feelings and reflect on ideas and activities. Use others as a sounding board for your progress and be brave in trying out new ideas in the classroom or with friends.

c) If you want to find excitement, adventure, or the unexpected, take an expansion pathway, and add to your already existing expertise by focussing on those aspects that are new to you. Try collaborating with colleagues as often as possible. Give the ideas a chance to develop but don’t linger if you think you already know something. You can always come back.

If none of the descriptions fit what you want to find, take an exploratory path and just start by reading in a linear fashion until you decide what the best approach for you will be.

2 Knowledge, Language, and Learning

This section will provide an argument for practitioners to reflect on their epistemological stance. Our teaching is explicitly or implicitly based on theoretical assumptions, and to keep abreast of new developments without following every new fashion, it serves us well to understand the wider context and be selective in the professional development activities we undertake.

I will first talk about connections between knowledge and language, and why language teachers need epistemology for their teaching. I will then go on to very briefly present a small number of learning theories that fit the context of online learning, and finally touch upon the distinctive needs of language teachers, as opposed to teachers of other subjects, in understanding creativity and power relationships in online learning environments to avoid inadvertently ‘silencing’ our learners.

2.1 Why Language Teachers Need Epistemology

In our everyday lives we take many things for granted: what our senses tell us about the outside world; explanations for experiences we cannot immediately feel, such as gravity; and the possibility of communicating with other humans and, to some degree, even animals. Moving between cultures can rattle some of this ‘natural’ understanding of the world. Different cultures take different aspects of reality for granted and question others. As language teachers we are familiar with these cultural differences, and part of our skills repertory is the ability to mediate between cultures and thus between divergent views of the world.

Comparing the way that different languages represent the world can help us to understand their underlying worldviews. To illustrate this, I will give a few examples relating to concepts, vocabulary, and grammar.

In Western (Indo-European) languages, we talk about the future lying before us, like a path we can set off on, like a horizon that can be reached. In contrast, Chinese expresses the future using prepositions indicating ‘behind’; the future, quite logically in this worldview, is in a space of the world that cannot be seen (it’s behind you) and the past stretches before us like a landscape that can be surveyed and catalogued, as its features are set, real, and visible. Other often-quoted examples are how the limits of our language limit what we can think (Reference WittgensteinWittgenstein, 1974), shape how we think (Sapir-Whorf hypothesis) and even what we can see, depending on the fine-grained vocabulary some languages offer compared to others that are satisfied with just a few expressions. This goes to show that teaching a language cannot be reduced to teaching the translation of words from one form to the other; words transport slivers of different cultures and different worlds. And so does grammar. A language with gendered nouns divides the world into quite distinct categories from a non-gendered language. A three-gendered world ‘feels’ unlike one with a two-gender division. Also, the way that cases structure a sentence or allow the expression of relationships between concepts can influence how the speaker of this language structures their world.

Diving into a new language, and learning to move between different languages, can thus become a truly transformative experience of learning (Reference MezirowMezirow, 1981). A good language teacher will be able to explain these differences and make them part of this mind-shaping experience. They need to avoid teaching cultural hegemonies (i.e., calling one of these world views the correct or most advanced one, privileging one way of seeing, explaining, or talking about the world, or claiming reality or truth for one structure or description). For a language teacher it is therefore important to be aware of their underlying epistemological beliefs, even more so than for a teacher of other subjects. The following sub-section will look at epistemologies and their impact on learning theories before moving on to those theories of knowledge acquisition that are more suitable to an online environment.

2.2 The Creation of Knowledge

Philosophers have been investigating how we know that which we believe to know about the world for millennia; they also question how reliable that knowledge is. In attempts to make their claim to a certain truth more convincing, they establish rules for knowing, rules for validating truth. One of the results of this constant striving for reliable knowledge is the natural sciences, with their focus on numbers, measuring, and comparing natural phenomena. On the other hand, philosophers also take a keen interest in language, as one of the tools or mediators we use to communicate our understanding of the world to other humans. Language is needed to share our reality and yet language is not neutral. Philosophers have debated how language forms our thoughts (e.g., Reference WhorfWhorf, 2012); how it limits what we can talk about (Reference WittgensteinWittgenstein, 1974); and how it is subject to power manipulation (Reference Heath and CarrollHeath & Carroll, 1974) as well as being able to exert power over people (e.g., Reference AustinAustin, 1962; Reference SearleSearle, 1969). Without any claim to philosophical depth, here is a short overview of several epistemological stances or beliefs on how knowledge can be achieved. This will become useful when considering how we expect our students to learn a new language and to adjust to a new worldview.

Naïve realism, our everyday stance of taking things for granted outlined in the previous sub-section, is not strictly speaking a philosophical stance, but it serves as a starting point to discuss epistemological questions. It has entered philosophical debates as ‘common sense’. That is to say, if all of us were permanently concerned with deliberating how we achieve knowledge, we would not be able to survive. Therefore, simply taking some things for granted in our everyday lives without questioning their truth is good enough for most people most of the time.

Once we start questioning, however, we start looking for something that can provide certainty in an attempt to understand the world or to know the reality around us. Our senses act as our windows to the world and can be used to provide us with ‘empirical’ information (empiricism); our mind can be used to establish rules and checks that can help to ascertain whether our senses are misleading us (rationalism). However, these approaches to knowledge generation can be flawed. Our senses can adapt to the environment, and thus a person growing up with a tonal language, for example, will hear the distinction between intonation and tonal changes, whereas a speaker with a Western mother tongue might find it difficult to distinguish between them and might need more effort or help. Our mind is not an empty box with a measuring device telling truth from lie. It is constantly formed and re-formed in reaction to experience, learning, and teaching. Considering this adaptability allows us to look at students’ mistakes as part of a language-learning journey: it shows how they have formed a new rule and how their thinking develops. The rule may not be correct but it is an indication of taking in new information.

The epistemology of materialism takes the potential flaws of empiricism and rationalism into account and claims that knowledge is derived through a complex interweaving of material conditions (the physical world around us and the shaped environment), historical conditions, and human intervention, such as social and cultural influences. This interweaving is particularly powerful when we consider the digital tools that form part of our students’ lives. They are physical entities, and at the same time they are cultural tools in a social environment. As teachers we can use them to influence our students’ thinking if we understand how they function in context.

Phenomenology takes a different avenue to avoiding rationalist or empiricist simplicity by introducing the consideration that human beings have a specific condition of being in the world. Through this, we are able to realise that our impressions are not necessarily a truth while we experience and while we think, but that they are our take on the outside and inside worlds – they are phenomena and not facts. Phenomenology or hermeneutics are interpretivist approaches and differentiate between the intellectual endeavours seeking to explain the world (like natural sciences) and those seeking to interpret the world (like humanities, for example): understanding and interpreting use other ways of ascertaining truth than explaining; and methods suitable for the natural environment may not necessarily be effective in the humanities. This may seem far from the everyday classroom experience of language teachers. However, we experience the divergent needs of students asking for simple and clear-cut explanations (e.g., grammar rules) and those longing for an empathic assimilation of the linguaculture (e.g., through art and literature). In a student-centred classroom we cater for both these innate human desires.

Another approach that has influenced our ideas about knowledge is psychoanalysis (Reference FreudFreud, 1900). By taking away the prerogative of the rational mind in human understanding and replacing it with the somewhat elusive concept of the Unbewusste (the subconscious mind), psychoanalysts claim that passion, desire, emotion, and drives interfere with our thoughts and actions. Where the conscious mind claimed by rationalist philosophers would allow us to clearly distinguish rational from irrational thoughts or emotions, the human mind as seen by psychoanalysts and their followers interlaces conscious and subconscious, rational and seemingly irrational. Psychoanalysis has influenced philosophical movements such as post-structuralism and provided arguments that place doubt on the existence of a truth altogether. This infusion of desire into language can be exploited by language teachers, not just in the service of increasing motivation but also in the acknowledgement of the power of language to shape our dreams and aspirations.

Regardless of the terminology used and the finer points of argument that distinguish philosophical positions, it is important for language educators to realise how powerful our position is. Firstly, truth and knowledge are fiercely debated and highly desired labels, and secondly, language itself is being used to create, confirm, establish, and defend claims about truth and knowledge, and not always in a transparent fashion.Footnote 1 For these reasons language teachers are at the forefront of helping others to make meaning away from their established and ingrained thought processes and patterns. They support learners in moving between not only different languages and cultures but also between different worldviews and epistemologies. The following sub-sections depict, in a bit more detail, a number of contemporary theories that can be used to explain the learning of languages as one form of knowledge creation.

2.3 Creating and Questioning Certainty

This sub-section will outline why a questioning attitude is important for language teaching. Entering a new language/culture/worldview shakes some of our assumptions and beliefs, as described in Section 2.1. This experience can be frightening for some people. Language teachers are experienced mediators between two languages/cultures/worlds and can help to overcome the fear of their learners by encouraging the appreciation of the unfamiliar and the joy of the new.

Creating knowledge or finding the truth are ways that human beings safeguard against the uncertainties of life, the ambiguity of meaning, or the discomfort of misunderstandings. Historically, religion had the role of providing certainty and truth but in the Enlightenment era, rationalism and scientific investigation replaced it. Positivism, the epistemology of natural sciences, and rationalism developed as a response to superstition and the hegemony of religious models explaining the world (for more details, see Reference Stickler and HampelStickler & Hampel, 2019). According to positivists, the outside reality can be proven by repeated measuring and comparing, relying on collecting facts and figures. This insistence on objective truth, as opposed to received inspiration or a religious monopoly for truth, has meant that every enquiry critically questions the potential interference from emotions, beliefs, and superstition. While this was a fundamentally revolutionary approach in its origins, rationalism and positivism have since created their own hegemony (Reference DenzinDenzin, 2009), marginalising other ways of describing or understanding the world around us.

As language teachers we understand the difficulties of dealing with ambiguity of meaning. We can see the insecurity caused in adult learners when their vocabulary in the second language is suddenly reduced to that of a child. Because we have to guide our students through this uncertainty and teach them to tolerate ambiguity, we need to be critical of the temptations of any absolute truth, whether this comes in the form of rational, scientific explanations or anti-rationalist inspiration. There are various critical responses to the hegemony of the one truth; the following paragraphs will describe just a few.

Building on materialist philosophies, constructivism has developed as an epistemology explaining how human understanding and knowledge are derived, not from an increasingly closer congruence with the outside world, but by being constructed by a mind that, in turn, is constantly influenced by physical (material), historical, and cultural conditions. In this perspective, no single truth can be found, as the position of the knower in relation to the known is different, not just for every individual but also for the same individual at different times in different places.Footnote 2

Also developed out of materialism, critical theories emphasise the power structures that influence our way of being in the world, often without conscious awareness on the part of those subjected to power. Power is embodied most obviously in political structures, but also, for example, in education, in fashion, in gender relations, and – most pervasively – in language. Combining the forces of critical theory’s understanding of power structure and psychoanalysis’ scepticism towards the rational mind, post-structuralism and deconstruction establish an ontology (a theory of what is) that undermines all claims for absolute truth, knowledge, authority, or authorship (Reference DerridaDerrida, 1972; Reference Deleuze and GuattariDeleuze & Guattari, 1987; Reference IrigarayIrigaray, 1980). Language teaching and learning – as a movement between worldviews – can help to establish a critical, questioning attitude in learners. This democratising tendency can be strengthened by employing ICT and pedagogies suited to online learning.

This short overview of possible epistemologies in the service of language teacher development leads us on to learning theories and their usefulness in language teaching. Although many learning theories are founded on psychological observations and studies rather than on a purely theoretical approach, their basis in different epistemologies is relevant for a deep understanding of teaching: a theory of how we learn needs an underlying understanding of how we know and of what is acceptable and accepted as knowledge.

2.4 How Learning Theories Can Help Online Language Teachers

From the naïve learning theory of the Nuremberg funnel (see Figure 1), the transmission model of knowledge being passed from an expert to a novice, through training approaches like behaviourism, where learning is seen as a getting used to new behaviours, learning theories have come a long way. In the context of this Element only a limited number of theories particularly relevant to online learning will be mentioned: socio-cultural theory, critical constructivism, ecological theory, and connectivism. An overview of different learning theories can be found in Reference Mitchell, Myles and MarsdenMitchell, Myles & Marsden (2019). An overview of learning theories and their link to technology-enhanced learning can be found in Millwood’s very comprehensive HoTEL map (Reference MillwoodMillwood, 2013).

Figure 1 The Nuremberg funnel where knowledge is poured directly into the brain

Socio-cultural learning theory is a collective description of a number of approaches that have in common that they emphasise the social elements of learning. ‘SCT [socio-cultural theory] is grounded in a perspective that does not separate the individual from the social and in fact argues that the individual emerges from social interaction’ (Reference Lantolf, Thorne, Poehner, van Patten and WilliamsLantolf, Thorne & Poehner, 2014: 15). Learning is seen, not as trained behaviour, nor as an accumulation of knowledge, but as an exchange of experience, helping individuals to adapt to a world where relationships with other humans play an important part. This adaptation is not one-sided: the society or culture the individual adapts to is not a solid, unchangeable entity. Rather, society, culture, and the environment accommodate the individual, and allow them to modify and re-interpret societal norms and cultural expectations (for more information, see Reference Lantolf and LantolfLantolf, 2000; Reference Lantolf, Thorne, Poehner, van Patten and WilliamsLantolf, Thorne & Poehner, 2014). The proximity of this learning theory to its materialist roots becomes obvious when we look at how history, culture, and society influence how we learn and are, in turn, influenced by us.

Taking a socio-cultural perspective links research into how learning takes place with pedagogy – the application of systematic interventions to make learning happen. Reference Compernolle and WilliamsVan Compernolle and Williams (2013: 278) refer to Vygotsky’s understanding of this connection as follows: ‘as Vygotsky argued throughout his writings, in order to understand the processes of human mental development, we must intervene. In formal, structured educational environments, this entails designing pedagogical programs that create the conditions under which developmental processes may be set in motion and observed.’ Underlying this understanding of learning is a relativist epistemology. In other words: what we observe as researchers or teachers is not a reality contaminated by our influence as observers. Rather the opposite: it would not exist unless interference of some form takes place.

Language teachers can use socio-cultural learning theory to evaluate and adapt their teaching tasks to a framework that privileges interaction and negotiation above the certainty of pre-established truth or rules. They will enable learners to interact with others and acknowledge that the culture they mediate is not a fixed entity but always in flux.

Constructivist learning theories can be seen as forms of socio-cultural theory, focussing on the mental processes. In Piaget’s socio-cognitive theory (Reference PiagetPiaget, 1986), structures of the mind are formed in a genetically pre-determined sequence; the development of children’s thinking follows the same patterns regardless of their environment. Whereas in Piaget’s theory the content of children’s thinking is very much determined by their interaction with their environment, Vygotsky’s socio-constructivist learning theory represents the stages of development reached by children as formed in an exchange between the inner workings of the mind and the stimuli received from outside, which have to be internalised before they can be processed (Reference VygotskyVygotsky, 1978). Radical constructivism (Reference Glasersfeld and LarochelleGlasersfeld, 2007) takes the notion of relativity even further in that mental processes can differ depending on where and in what contexts they are formed, and no reality exists beyond the constructions individuals form in their mind.

For language teachers, the constructivist theory guides them towards emphasising and appreciating their learners’ effort in constructing their own rules and mental maps of the target language. Rather than correcting mistakes, language teachers will celebrate them as attempts by the learner at actively participating in knowledge creation.

Critical constructivism (Reference KincheloeKincheloe, 2005) combines the epistemological stance of constructivism with the political agenda of critical pedagogy (Reference FreireFreire, 1996; Reference IllichIllich, 1970; Reference RogersRogers, 1983) to argue for an education that questions the status quo, is sceptical of all forms of privileged truth or knowledge and pleads for a democratic classroom where students and teachers need to work on understanding their position in relation to each other, to the curriculum, and to the wider world.

This approach fits well with a forward-looking professional development for language teachers in online environments where power structures can be defined anew with every new tool developed. Language teachers employing this critical learning theory will make certain that they acknowledge their own privileged position and question the necessity of prescribed standards of accuracy or politeness. As language teachers we may be used to a position of power. Deliberately foregoing this privileged position changes the dynamics in the classroom. This can be achieved by the skilful introduction of digital tools and online platforms that disperse power.

Ecological theories of learning depict similar conditions as socio-cultural theories: the way we think is influenced by the environment we live in; humans adapt, like other animals, and their survival is dependent on successful adaptation. However, rather than privileging human or social influences, ecological theories consider all the elements of the environment. As ecological theories developed from a science approach to human psychology, the underlying ontological assumption (Reference Twining, Heller, Nussbaum and TsaiTwining et al., 2017) is one that claims an existing reality, an environment that sends out information stimulating our senses. Our senses, in turn, adapt to the stimuli, process the external information, and pick out what is relevant for the human experience in the given context. A term often used in ecological learning theories is the idea of ‘affordances’ (Reference Gibson and GibsonGibson, 1979). An object is perceived by a human in an environment. Rather than simply perceiving (objective) properties of this object, the human interprets the object in the context and imbues it with affordances: what can this object/condition do for me in this context? How can it be useful?

For language teachers in online teaching contexts, the ecological learning theory is a constant reminder that interaction online is not only mediated by language but also by technology. Features of the learning environment have to be interpreted as affordances to allow learners to make the most of it in their language-learning efforts. Tools, online spaces, and information can be exploited in the interest of learning by making the learners aware of their potential, their affordances.

There are similarities in ecological and socio-cultural descriptions of the environment encountered in learning a new or second language (L2), and in the de-emphasising of the individual through the concept of mediation (Reference Wertsch, Daniels, Cole and WertschWertsch, 2007). Human mediation is not always necessarily present in a language-learning event. Reference Compernolle and WilliamsVan Compernolle and Williams (2013: 279), for example, claim that ‘L2 pedagogy encompasses any form of educational activity designed to promote the internalization of, and control over, the language that learners are studying, whether or not a human mediator (e.g., a teacher) is physically present and overtly teaching’. This becomes particularly relevant when we move towards online language learning.

Building on connectionism (Reference GasserGasser, 1990), connectivism is a relatively recent addition to learning theories (Reference SiemensSiemens, 2004; Reference Siemens and ConoleSiemens & Conole, 2011). Comparing the distributed knowledge present in a large online system – a massive open online course (MOOC), for example – to information processing in neural networks in the brain, connectivism describes how by virtue of being connected, individuals can utilise more information and distribute knowledge across nodes. Connectivism thus de-emphasises the human factor; and tools such as ICT take on an important role. Connectivism is ideally suited for the development of MOOCs and other open online resources as it describes how learning is a process of finding patterns and making connections, thus developing networks and nodes. There is no need for a masterplan or ‘master instructor’ as learners will create their own connections and networks. As a learning theory, connectivism has its critics. However, whether or not connectivism is a unique learning theory (Reference DownesDownes, 2019; Reference Kop and HillKop & Hill, 2008) or just an extension of the ecological learning theory is less relevant than keeping in mind the importance of technological mediation in online spaces (Reference WertschWertsch, 2002).

2.5 Why Online Language Learning Is Different and How

As mentioned in Section 1.6, online language learning is different from face-to-face communication. Regine Hampel argues that technology ‘disrupts’ (Reference HampelHampel, 2019); it disrupts the interaction patterns we expect in face-to-face classrooms and the modes of communication; it opens the classroom to the real world. In other words: it changes the learning environment. One of the reasons that this ‘disruption’ impacts on our language teaching is that many of the signals we rely on when sharing physical space with an interlocutor are missing online. We cannot determine exactly where our interlocutor focusses their eyes (Reference Develotte, Guichon and VincentDevelotte, Guichon & Vincent, 2010; Reference LiLi, 2021), we cannot hear all the potentially distracting interferences they have to cope with, we are not always aware when they use additional means to support their comprehension or language production (Reference SatarSatar, 2011). However, rather than claiming that online communication is shallow or lacking depth, we should look at the advantages of online learning, such as the ubiquitous access to resources and opportunities for communication and learning in social spaces. We need to investigate the differences that help us understand the meaning making that takes place online, which in turn will allow us to support online language learners in their efforts.

For example, if we consider time in online language classes, we can either focus on the time lag produced by data transfer across vast spaces, or we can focus on the way that online conferencing platforms often allow parallel communication in different modes (Reference Hampel and SticklerHampel & Stickler, 2012; Reference Shi and SticklerShi & Stickler, 2018). Learners can read a text chat message, listen to spoken interaction and consult an online dictionary – not necessarily all at the same time, but at a time that is convenient for them. Any expectations classroom teachers may have that they can control, or at least survey, all interaction and action going on during the learning event have to be left behind if the learning space is an online platform.

This difference in communication can be seen on a purely practical level as something language teachers have to train for, to practise, and consequently adapt their teaching style. On a deeper level, however, it can also be considered as an epistemological shift: new ways of ensuring that a common understanding is achieved by employing different modes and different checks. To exemplify this, we can look at synchronous verbal online interactions as an attempt to make meaning. A phenomenological perspective would focus on the human experience of what our senses tell us, shaped by our personal history, filtered through our mind. This would normally allow us to empathise with a fellow human being, using a shared language to make meaning together. The online space takes away some of the sensory input normally shared by face-to-face interlocutors; however, there is still our shared basic knowledge, our shared humanity. Taking some of the empathy employed in face-to-face communication for granted might mislead us in online communication, when we assume the person on the other side of the screen might just follow our gaze, experience a similar environment as we do, or is able to project their presence into the online room as they would in a shared physical space. An ecological perspective might try to unravel the impact of the different elements that shape our communication attempt: some of them will be technological, some sensory and human, and some take shape only in the interface between human and technological spheres.

Second-language learning is a special case of online communication in various aspects. Firstly, at least one party of the online communication in a learning event might not be fully able to express their intention in a verbal way; they might also inadvertently express ‘foreignness’ through a different accent, limited vocabulary, or an unusual choice of structures. This entails an inequality of means – at least of verbal means – of expression. The unequal partner might find non-verbal means to make up for this lack but, again, these means may be different online than in a physical shared space; and in a language-learning situation verbal expression might be privileged, consciously or unconsciously, by the teacher. Teachers need to be aware of this inequality, but also of the fact that for various reasons, the learners might not be able to project all they want to project into their shared online space.

Through their training, language teachers have a number of skills available for coping with these new epistemological requirements. They have a language teacher’s trained ability to fill in for missing ‘words’, be they verbal expressions or other means of communication imperfectly employed. As cultural mediators, language teachers also have a sensitivity for miscommunication and talking at cross-purposes. They have developed a third eye for spotting potential misunderstandings and a number of strategies to counteract them. And finally, they can also bring to the new learning situation the ability to further in their students (as well as in themselves) a make-do attitude and a tolerance of ambiguity, making the best of guesswork and imperfect or incomplete communication attempts.

Traditionally, making meaning would be seen as a uniquely human prerogative but, with the advent of intelligent technology (e.g., artificial intelligence or AI), we have to allow for machines searching for meaning or understanding as well. Connectivism, to a certain extent, looks for this special place of technology in human meaning making, describing the shared space of online human-to-human communication as influenced and shaped by ICT. Does this mean for language teachers that we should give up our expertise in pedagogy and rely on the ‘wisdom’ of the machine to create learning environments? We will return to this question in Section 6 of this Element, which looks at the future of online and technology-supported language teaching. In the next sub-section, we consider the ways in which understanding the epistemological bases of learning theories can help us shape our own practice and professional development.

2.6 Theories for Online Language Teaching

So how can the learning theory be used to understand and develop online language teaching? Starting with the simple caricature of a naïve transmission model of learning, the online language teacher would be expected to pass on their knowledge of the L2 to their students. This could be done by talking about it, by listing grammar rules and vocabulary in translation, by modelling L2 pronunciation and intonation, and by providing ample input in the L2. In behaviourist models, again simplified, the online teacher would conduct drills for students, forcing them to produce output in repetition and imitating the teacher’s pronunciation. As language teachers we know that these methods do not work in the face-to-face classroom, so why would they work better online?

Looking at socio-cultural learning theories, the importance of others in the learning environment immediately becomes clear. This leads to collaboration and group work as important features of the online classroom. Based on this understanding that we learn with others, we can conclude that the content of the communication should be relevant to the individual: no drills about irrelevant grammar examples but real-life statements about personal experiences, performative structures that change what is happening in the real world, empathetic listening, and respect for the interlocutor become central features of this learning and teaching situation.

For critical constructivism, the power issue in the (online language) classroom becomes even more central (Reference KincheloeKincheloe, 2005). The teacher, although privileged through competence in the L2, is still part of the group, an interlocutor among others, who may be able to provide scaffolding (see Reference Lantolf, Thorne, Poehner, van Patten and WilliamsLantolf, Thorne & Poehner, 2014) where needed but will not abuse their power to select the relevant text and information for each learner. Learners select what they want to present, and their online persona might be quite different from the visible physical person in a classroom. Their world is their own, and only part of this world is shared within the online classroom. In this sense, online learning can be more learner-centred and tailor-made than face-to-face classes and lends itself to a re-consideration of power relationships.

Taking the ecological perspective seriously, teachers need to be aware of the affordances of online learning spaces and make their learners aware of them, as well. This means that teaching often takes place in the form of preparation, familiarising oneself with the space, enabling learners to explore and exploit the affordances of networked and online learning and sharing techno-expertise as well as language competence equally between learners and teachers (Reference Heiser, Stickler and FurnboroughHeiser, Stickler & Furnborough, 2013). A similar conclusion can be drawn from connectivism for teachers: making sure that learning can be understood as making necessary connections, finding appropriate resources (including other learners), and realising affordances is a good starting point for a connectivist learning experience.

Language teachers should not ignore epistemological questions but embrace them as part and parcel of their work: as a chance for bringing their unique skills to online communication events and helping to make them successful spaces for shared cognition (Reference O’Rourke and SticklerO’Rourke & Stickler, 2017).

2.7 Task

A reading list on technology is outdated before it gets into print. Therefore, suggested further literature for this section will take the form of four recommendations on how to stay abreast of current developments in research and pedagogy.

2.7.1 The Systematic Approach

To receive information on new publications in a specific topic area, you can set up an online literature alert. Online search engines (e.g., Google Scholar) or reference management systems (e.g., Mendeley) allow you to set up an email alert. Based on your search criteria or specific keywords, you receive a message as soon as new publications enter the catalogue of your chosen software. Of course, these alert systems are not perfect, and you might get some irrelevant articles. On the other hand, the email alert might just remind you to search for new relevant material.

2.7.2 The Random Approach

If you already have a reading list or a selection of articles you always wanted to read, you can set yourself a time every month to read just one article, and maybe get inspired to dive deeper into the topic. Follow this up by practising what you learned, reading more on the same topic, or discussing it with colleagues. Online conferences and webinars are also a good source for information if you want to move from the random approach to a more systematic one.

2.7.3 The Social Approach

Social media have become an almost indispensable source of information for teachers. Twitter, for example, has a number of online communities of language teachers exchanging and sharing information (e.g., communities identified by the hashtags #MflTwitterati, #LangChat, #ELTchat). These and other hashtags can be searched on Twitter without prior registration. Once you find an expert or a group who deliver reliable and up-to-date information, you may want to follow them on Twitter, and follow up on their recommended reading or announcements of new articles. The advantage of social media is that new research papers are advertised as soon as they are published, and they are pre-filtered so you don’t have to search through everything that would appear in a search engine.

2.7.4 The Expert Approach

As a language teacher or researcher you are already knowledgeable and experienced in your particular field. You can give back to the academic community, for example, as a reviewer for journals. Editors often look for volunteer peer reviewers, and you will gain by getting advance access to research. As a language teacher you also bring a very important skill to peer reviewing: you know about giving carefully gauged and supportive feedback and you can balance critique with encouragement. Of course, there is work involved but the overall benefit of reading exciting new developments in your area of interest may outweigh the effort invested.

3 Pedagogy: Fostering Online Language Learning

This section will first look back at the history of educational theories and language-learning theories. It will link these to online teaching, CALL, and the changes continually shaping the contexts in which we teach (the STAR factors mentioned in Section 1.5). It will then go on to explain in detail the three-dimensional framework of technology use in language teaching (visibility of technology, authenticity of communication, and teacher intervention; Reference Shi, Stickler, Shei, Zikpi and ChaoShi & Stickler, 2019). Examples of language teaching practice using technology will illustrate the framework and bring it to life by linking it to pedagogical approaches before returning to the relevant underlying theories.

The task for this section is a reflection task and might take you back to when you first started teaching (or learning) a language.

3.1 Histories and Changes

You could be forgiven if you think that educational theories are like fashions – changing ever so often – and that as a teacher you are expected to follow the latest fad. To some extent this is certainly true, and there are or were certain language pedagogies that were fashionable for a short time and vanished quite quickly to be replaced by a new experiment or idea. In any case, language teaching has a history. Educational policies and the wider political context have shaped the language teaching curriculum, for example, in selecting which languages should be learned. There are also changes following the broader developments in educational ideas, learning theories, or expectations of a well-rounded, well-educated person (Reference Pulker, Stickler, Vialleton, Plutino and PoliscaPulker, Stickler & Vialleton, 2021).

Some pedagogies have influenced the profession for decades: for example, the change from a knowledge-based concept of language learning (engendering, for example, the grammar-translation method) to a communication-based concept, which is at the root of the communicative approach and has led to task-based (Reference EllisEllis, 2003) and action-oriented (Reference PiccardoPiccardo, 2010) pedagogies. A skills-based concept of language use, on the other hand, has engendered teaching methods such as the behaviouristic drill (‘and kill’) method of frequent repetition, or the audio-lingual method of training the ear and speech organs to get used to the form and feel of a language.

As language learning encapsulates different aspects, such as knowledge about the structures of a language, recognition of its forms, the practice of producing its sounds, the motivation to establish successful communication with its speakers, the need to accomplish a task, and the cultural sensitivity to choose an appropriate way of communicating, this section will not recommend any particular pedagogy but instead map out different practical suggestions for getting students to learn an additional language, and attempt to link these to the technology use that is the best fit to achieve this goal. In starting from the pedagogical aims, we avoid a techno-centric approach that focusses too much on the tool or the medium and is in danger of losing track of the aims of language teaching. As Breffni O’Rourke put it, ‘whatever a new technology appears to promise, it does not bring about worthwhile pedagogical innovation in and of itself’ (Reference O’Rourke and O’DowdO’Rourke, 2007: 42).

3.2 CALL History

Computer-assisted language teaching and learning (Reference Levy and HubbardLevy & Hubbard, 2005) is a relatively recent field in language education theories, and yet it has already undergone changes in its pedagogy and boasts a number of historical overviews. From early developments onwards, computers have been used as a means to present and automatically assess language drills such as identification of grammatical forms or gap-fill texts. In more sophisticated programmes, such as language quests, cultural and metalinguistic information is included to provide a rich, pre-designed learning environment for predominantly independent learning. In a later stage, enabled by widely available connectivity, network-based language teaching (Reference Kern, Ware, Warschauer, May and HornbergerKern, Ware & Warschauer, 2008) uses computers as tools to connect learners with the real world and with each other.

If you are interested in more detailed historical overviews of the development of CALL, you could consult one of the following articles: Reference BaxBax (2003); Reference Coleman, Hampel, Hauck, Stickler, Levine and PhippsColeman et al. (2010); Reference JungJung (2005); Reference Warschauer and HealeyWarschauer and Healey (1998). A tool-focussed description of how the use of ever more sophisticated technology changed alongside pedagogical developments at one distance-teaching institution can be found in Reference HampelHampel and de los Arcos (2013); and a selection of CALL studies, exemplifying how the research approach to CALL has changed over time is available in the article ‘TELL us about CALL’ (Reference Stickler and ShiStickler & Shi, 2016). If you want to keep up to date with the latest technology in the field from a practice point of view, the regular columns of Robert Godwin-Jones in the Language Learning and Technology journal are a good base. The COVID-19 crisis and the imposed move to online teaching have inspired numerous articles and collections reporting on good practice or ad-hoc evaluation of changes. Time will tell how many of these articles are concerned with sustainable pedagogic changes or whether some are fleeting impressions engendered by the immediate need of teachers and researchers alike.

3.3 Technology, Communication, or the Teacher?

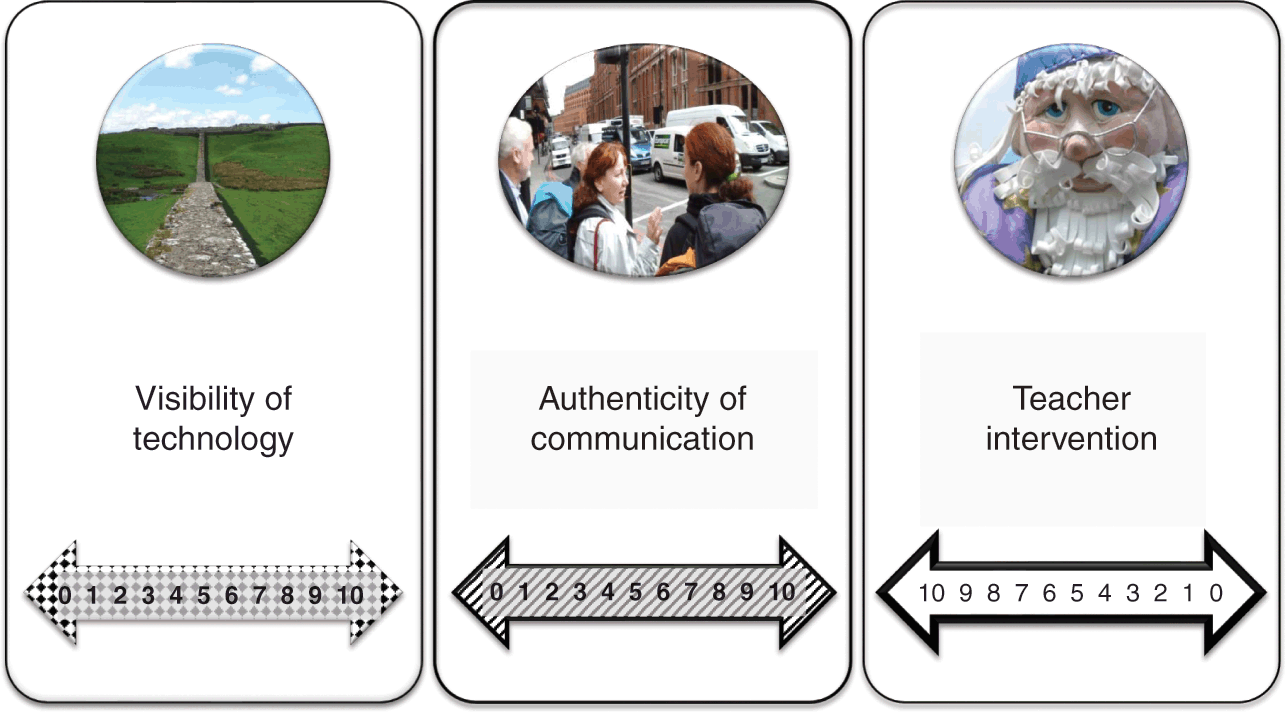

In Section 1 we looked at a way of describing the given or pre-determined structure of language teaching environments (STAR factors). This section will introduce the axes of change. Technology does influence what happens in a language classroom, and not always in the way the teacher intends or realises. For the development of online language pedagogy, a systematic overview of how different types of technology influence the teaching and learning environment is indispensable. For this purpose, Reference Shi, Stickler, Shei, Zikpi and ChaoShi and Stickler (2019) have developed a framework that allows us to categorise examples of language-learning technology in three dimensions or along three axes: the visibility of technology, the authenticity of communication, and the directiveness of teacher intervention (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Three axes of technology in language teaching

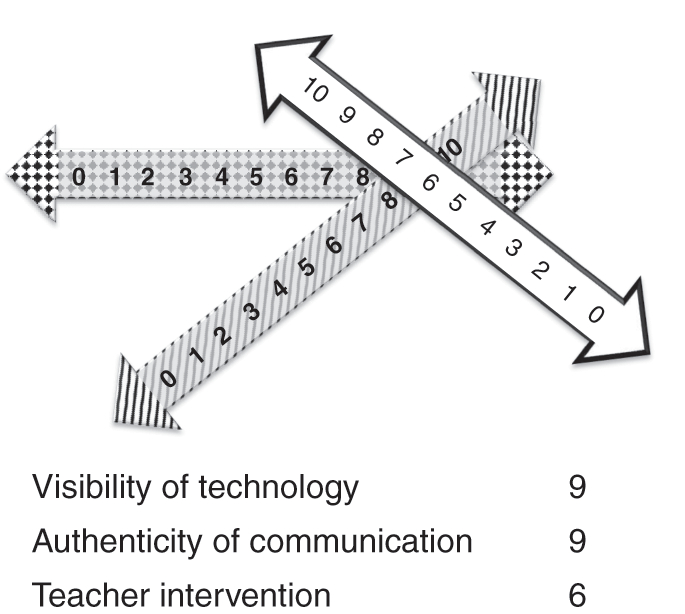

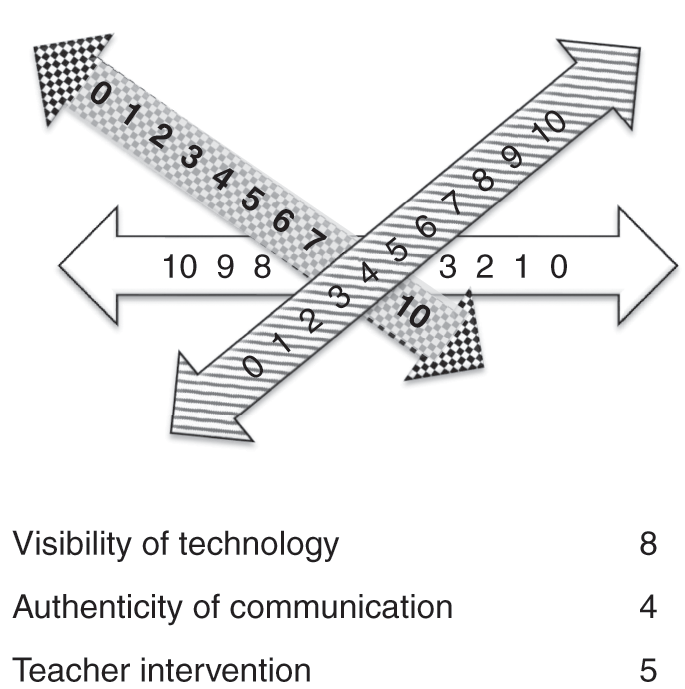

The three axes are best visualised as the three dimensions of a cube or three axes that overlap and interact to emphasise how they are interconnected and mutually dependent (see Figure 3). The axes are developed in more detail in the following paragraphs.

Figure 3 Interaction of the three axes

3.3.1 Visibility of Technology

The visibility of technology is described on a scale of 0 (normalised) to 10 (highly visible). Everything, from pen and paper to tablets and smartphones, can be labelled as tools and technology; and the use of a specific technology influences the way we think and communicate (Reference KrämerKrämer, 2010). Arguably, newer, less familiar technologies are more visible to us. We notice their use, whereas other technologies, such as counting or the use of pen and paper, become ‘normalised’, as Stephen Bax called it (Reference BaxBax, 2011). The visibility of technology as technology thus moves towards zero (0). The same normalisation happens for language-learning apps: when the tool or app is in the foreground, the focus will be on the technology (10), but the more we use it, the less visible it becomes. If a teacher is keen on always introducing new and trendy tools or apps, learners might also focus on the technology rather than the language-learning task. Alternatively, if the choice is left to learners, they might well choose a tool they are familiar with, one they use in their personal life, or one they have found reliable or preferable to the tool the teacher suggests.

3.3.2 Authenticity of Communication

The authenticity of communication is described on a scale of 0 (= inauthentic) to 10 (close to authentic). However, first, a word of warning: authentic language or authentic communication has always been an elusive concept. In the age of networked communication, language itself has changed: language @ internet (Reference AndroutsopoulosAndroutsopoulos, 2011) is different from the written form used in the first half of the twentieth century, and different from spoken language. To place a language-learning event on the authenticity scale, this change needs to be taken into account, rather than measuring online language use against an outdated pre-digital form of the target language.

As mentioned, language learning takes place in a tension between the training of skills and the authentic experience of real-life communication. Training is important, but so is the authenticity of communication. Over time, language didactics have moved from emphasising one end of the scale (training, drills, repetition; 0 = inauthentic) to the other (communication, tasks, action, projects; moving towards 10 = authentic). At the same time content is moving from discrete language items to a holistic view of language, and learner involvement from a rather passive, consuming attitude to active and creative co-construction. Technology can be employed for either purpose. From early drill-and-kill activities, such as gap filling, or Cloze tests, to encouraging interaction with authentic target-language media (Reference Hanna and De NooyHanna & de Nooy, 2003), activities have been planned to fit the selected pedagogical approach. The communicative approach has brought forward sophisticated scenario-based software, such as web quests (Reference KoenraadKoenraad, 2006); and task-based and project-based language learning. These methods make use of authentic resources, which are independently researched and employed by the learner(s) to complete a task or project.

3.3.3 Teacher Intervention

Teacher intervention is described on a scale from 0 (very autonomous learning) to 10 (very teacher-centred). In the times of face-to-face language pedagogy, we used to talk about autonomous learning (= zero teacher invention) as something that happened mainly outside the classroom (Reference HolecHolec, 1981). In an online environment the emphasis shifts: learners are working away from the direct control of a teacher and thus have to decide independently when to get in touch and how to follow – or not follow – the directions of a teacher (Reference FischerFischer, 2007). The weight, depth, and visibility of teacher interventions thus depend not only on the teacher’s intention but also on the learner’s willingness to follow the guidance. How much planning the online language teacher invests in beforehand to control and direct what language and content their learners will find when searching the web, for example, is a pedagogic decision, as is the choice of how much control the teacher exercises over their learners.

Acknowledging the role of technology and understanding how it impacts on the learning of students gives teachers the option of selecting different tools for different purposes in language education, and shifting the emphasis from more to less visibility of the technology; less to more authenticity of the communication taking place during language learning; and from more to less teacher intervention or, on the flipside, from less to more learner choice and autonomy. Considering these three axes as scales from one extreme to the other rather than inflexible definitions can help describe the different requirements of technology use in language teaching, and empower teachers to take the initiative and shift – if only a little – their use of technology and their teaching practice.

The three axes will be used for the task at the end of this section and for the practical considerations in Section 4. For some examples of where particular tools or teaching practices can be placed, see Section 4.4 and Reference Stickler and HampelStickler and Shi (2019).

3.4 Some Examples of Technology-Enhanced Language Teaching Practice

Rather than providing yet another overview of the various pedagogies of online language teaching, I have chosen some illustrative examples of language teaching and learning practice that make use of the ease with which the Internet connects people and grants access to authentic sources of information in many different languages. These types of learning are made possible by the richness of resources easily available on the worldwide web, by the ever more sophisticated use of computer-mediated communication (CMC), and by the ubiquity of mobile and small, hand-held devices and their associated applications.

I will link the following examples, from simple repositories to fully online synchronous tutorials, to the elements of the STAR structure, highlighting where space, time, and teacher role are determined by tool or task choice and where different options are possible. For the moment, I will leave out accreditation and assessment, returning to it later in the section.

A common and widespread use of technology in language teaching is the collection of tasks, activities, and materials in online repositories or inventories. Some of these repositories are freely accessible open educational resources (OERs), some are teacher-created, and others are institutional. One tool-focussed example is the Inventory of the European Centre for Modern Languages (ECML), which collects useful apps and tools specifically recommended and described by language teachers (www.ecml.at/ict-rev).Footnote 3 The use of the online space is purely ancillary, as the medium does not impact on the pedagogy of the tasks or materials itself. However, the space can be made interactive by allowing the sharing of and commenting on resources. Communication is online (Space), asynchronous (Time), and teacher-focussed (Role).

A similar use of online communication is the setting and collecting of homework tasks in an online environment, for example a virtual learning environment (VLE). The pedagogy of tasks does not change; however, the administration of the task is made easier by a systematic overview, by digital tracing and recording. Communication is blended with just some part of the course allocated to online work, asynchronous for this specific use, and it is teacher-focussed as the teacher sets, collects, and evaluates the work.

eTwinning or online classroom partnerships are popular forms of exploiting online communication for language practice. eTwinning is seen as more suitable for younger learners. The twinning is pre-arranged by teachers and takes place on secure and access-limited platforms (e.g., eTwinning Europe: www.facebook.com/ETwinningeurope) thus guarding young learners’ privacy and online safety. Activities often centre around a topic or are organised in the form of projects (Reference FearnFearn 2021). eTwinning classes can use a lingua franca (often English) to communicate, thus practising a language that might not be a mother tongue to either partner class. The online communication enhances face-to-face teaching, so the use of space is blended; communication is mainly asynchronous during the twinning projects but can contain some synchronous elements. The teacher still has the central role.

eTandem links learners of different languages with speakers of the language they learn online. Switching between the two roles, a learner becomes in turn the expert informant or even an informal teacher of their own first language and thus supports the eTandem partner in their learning. Tandem is chiefly an autonomous form of learning but there is some support through teachers or institutions. eTandem networks provide platforms for linking individual learners or groups of learners and also model tasks for various language combinations and competence levels (Reference Brammerts and WarschauerBrammerts, 1996; Reference Lewis, Coleman and KlapperLewis, 2004). eTandem is fully online (Space), although it is sometimes integrated in face-to-face courses. The communication is synchronous and asynchronous, depending on the tool the learners choose and the skills (speaking or writing) they want to practise. Teachers take the role of language advisors (Reference Stickler, Mozzon-McPherson and VismansStickler, 2001; Reference Stickler, Lewis and Walker2003) and the competent or native speaker eTandem partner often takes on some parts of the teacher role.

An example of fully online language learning is an online lesson or tutorial with video or audio-conferencing software. If it is planned rather than used as a substitute for face-to-face classes, online tuition can change the way learners communicate (Reference Heins, Duensing, Stickler and BatstoneHeins et al., 2007; Reference Heiser, Stickler and FurnboroughHeiser, Stickler & Furnborough, 2013), enhancing the experience through a combination of digital tools (Reference Hampel and SticklerHampel & Stickler, 2012) such as presentation software, online dictionaries, and notice boards. Although space (online) and time (synchronous) are set, it depends on the teachers whether they take centre stage or hand over more responsibility to learners.

After these examples ranging from an ancillary use of online repositories to fully online teaching, the next sub-section will look at pedagogical approaches that can enhance the online teaching of languages.

3.5 Finding a Balance of Power: Choosing a Pedagogic Approach

Certain pedagogical approaches lend themselves more readily to an online environment than others. That is not to say that you cannot adapt a VLE or an online course to whatever pedagogy you favour, but rather that affordances of online learning environments enable new and exciting teaching and learning strategies to come to fruition (Reference Stickler and HauckStickler & Hauck, 2006). This section will provide a couple of examples of successful online activities and their underlying pedagogical decisions. An argument for the expansion of pedagogies used in face-to-face language classrooms to include the affordances of the online learning environment will be put forward in the next section.

As mentioned earlier, language learning entails an imbalance of power: the competent speaker of the language possesses the means to express with more ease their intended meaning. Not only will they be able to express more accurately what they mean using varied vocabulary and structures, they will also find pragmatic and rhetorical means for persuading the interlocutor of their argument if they aim to do so. In addition, a competent speaker can employ emotional undertones, giving their speech depth, warmth, ironic distance, or humour with greater accuracy and ease than a learner or novice speaker of the language.Footnote 4 This imbalance is in addition to the power difference between teacher, as carrier of knowledge, and learner, as seeker of knowledge.

Online language teaching extends a number of ways to deliberately address this imbalance of power. In the following, I will describe three examples of shifting the balance of power in online learning spaces.

Language teachers do not have to be technology experts. The well-known TPACK model, describing the combination of technological, pedagogic, and content knowledge required of teachers unquestioningly assumes that every teacher will need to acquire technological skill (Reference Tseng, Chai, Tan and ParkTseng et al., 2020). However, when I, together with colleagues, conducted a survey, asking 595 language teachers participating in ICT-related training workshops how they feel in situations where their students know more about ICT than them or are more skilful with technology than them, the response was overwhelmingly relaxed: teachers can admit to not knowing everything, they can cope with not being the expert in the room, and are often looking forward to sharing responsibility with their learners (Reference Germain-Rutherford, Ernest, Hampel and SticklerGermain-Rutherford & Ernest, 2015; Reference Hampel, Germain-Rutherford and SticklerHampel, Germain-Rutherford & Stickler, 2014). To quote just one example response:

‘ICT is a not just ‘one’ thing to know, it is a vast area of learning. So, as with all subjects, there may be students in your class who know more about one specific thing. Nice! The ‘expert’ can have a go at trying to share his or her knowledge effectively.’.

This relaxed attitude and willingness to share responsibility in class might not be true for all teachers in all cultures and learning environments, however, the survey collected responses from teachers across twenty-three countries in Europe teaching languages at educational levels from primary schools to universities.

The pedagogical approach that can be drawn from this finding is: sharing expertise.

To position it in the framework of the three axes, this demonstrates a deliberate move from teacher-centred to student-centred strategies, inviting learners to take responsibility for their own learning and for supporting their peers.

Online language learning offers the advantage of easily arranged authentic communication with competent speakers of the target language. As briefly described in the previous sub-section, language teachers have exploited this affordance from the 1990s onwards, and arranged eTandem learning as a relatively autonomous form of peer-supported language learning (Reference Brammerts, Lewis and WalkerBrammerts, 2003; Reference CzikoCziko, 2004; Reference Lewis, Gola, Pierrard, Tops and Van RaemdonckLewis, 2020; Reference Little, Chambers and DaviesLittle, 2001). By finding learners of different target languages and pairing them online with native or expert speakers who are also language learners, a learning situation is created that facilitates a unique switching of power: A learner of German with English mother tongue, for example, is paired with a competent German speaker who wants to improve their English (Reference O’Rourke and O’DowdO’Rourke, 2007; Reference SticklerStickler, 2004; Reference Stickler, Emke, Benson and ReindersStickler & Emke, 2011). With teacher or language advisor guidance (Reference Lewis and WalkerLewis & Walker, 2003; Reference Stickler, Lewis and WalkerStickler, 2003), the two exchange communication online, switching from English to German at agreed intervals. A learner – and less than competent communicator – in one language thus becomes the expert communicator in part of the learning event. Less than a teacher but more than a casual interlocutor, eTandem partners can develop an equilibrium of power, gaining confidence as communicators in their learner role and understanding (or empathy) in their expert role.

The pedagogical approach here is: switching power. The teacher role moves along the axis from expert in the centre to a facilitator, and organiser who prepares the ground but then moves into the background, staying available as advisor when needed. Communication, on the other hand, moves up the scale, to almost fully authentic (8 or 9). The individual exchanges between eTandem partners might well approach full authenticity; however, the setting is still pedagogic and based on the agreement of a peer-learning exchange.

As a third example, I will focus on the ease with which authentic texts and information are available in online language learning. Teachers can prepare materials for the classroom but also send their learners on webquests (Reference AydinAydin, 2016; Reference KoenraadKoenraad, 2006) or set them tasks (Reference EllisEllis, 2003) to find authentic information online. With the help of multilingual websites or machine translation, even the more complex texts become accessible for lower-level learners. In addition to teacher-led tasks or quests, groups of learners can also work more independently. They select a topic or a project (Reference Elam and NesbitElam & Nesbitt, 2012) they are interested in, negotiate distribution of tasks, collect information, prepare a presentation in the target language, and share this with the class. In addition to practising receptive language skills in gathering online information, and productive language skills when presenting their project results, learners also gain skills in digital literacy by searching for, selecting, and evaluating information; summarising, citing, and incorporating sources; and communicating online with peers, their teacher, and sometimes also target-language interlocutors. Learners are also encouraged to develop or increase their group and team working skills, their collaboration and their project management skills.

This pedagogic approach, taking advantage of the affordances of the online space, is known as project-based language learning (Reference SampurnaSampurna, 2019). In terms of this framework of technology use (Reference Shi, Stickler, Shei, Zikpi and ChaoShi & Stickler, 2019), the approach limits teacher intervention considerably (2 or 3), as even the choice of topic is left to students. The authenticity of communication is high in the receptive phase of project work, where students gather information from authentic online sources (7 or 8). However, during the production phase, where lower-level students might feel hesitant to speak or write for an authentic target-language audience, the learning space can potentially be made safe (and thus less authentic) by limiting the online audience to invited peers, other teachers, or sympathetic target-language speakers.

3.6 From Pedagogic Choice to Technology Use