On the Argentine capital's premiere stages, Western concert dance forms and pre-Columbian indigenous themes continually crossed during the twentieth century. One day in 2011, I experienced one of these crossings as I sifted through archival materials at the General San Martín Cultural Center in Buenos Aires. Among the center's audiovisual collection, I encountered a recording of a public television program called Buenos Aires, ciudad secreta (Buenos Aires: Secret City, 1994–2004). In a 1995 episode, the celebrated Argentine choreographer Oscar Araiz is asked to comment on the Argentine and international legacies of Vaslav Nijinsky, the star of the influential Ballets Russes. Araiz's commentary framed journalist Germinal Nogués's discussion of the Ballets Russes's successful 1913 Buenos Aires tour and the ultimately unrealized Caaporá project (1915), an Argentine ballet that was slated for choreography by Nijinsky and based on a legend from the Guaraní indigenous group (Buenos Aires, ciudad secreta). As I considered Araiz's comments on Nijinsky's work, I asked myself: Why did the creators of Caaporá call on Nijinsky to choreograph the work? Why invoke a pre-Columbian indigenous legend at the turn of the century, a moment intensely concerned with all things modern? Why feature Araiz in this television episode on Nijinsky, and where did his own works based on pre-Columbian themes and his well-known version of La consagración de la primavera (The Rite of Spring, 1966), the Igor Stravinsky score originally choreographed by Nijinsky, fit into this story?

Taking up these questions, this article argues for the central roles of the unrealized Caaporá and Araiz's Consagración in the establishment (1915) and reimagination (1966) of concert dance as a site of modernity in Argentina. Both works danced modernity through imagined indigenous bodies and centered two influential figures with privileged relationships to the modern. Rather than offer a comprehensive account of Argentine concert dance works that incorporated mythic pre-Columbian themes, this article demonstrates how Caaporá and Consagración marked critical transitions in the ongoing strategy to fold indigenism into the dancing of modernity. A movement in literature and the visual arts as well as concert dance across the first half of the twentieth century, Latin American indigenism combined “pre-Columbian imagery and symbols” with the European artistic traditions and trends that cultural elites championed as part of postcolonial nation-building projects (Kirkpatrick Reference Kirkpatrick and Schelling2000, 184).

In Argentina, indigenism developed in the early twentieth century as Argentine artists attempted to cultivate a local national identity while simultaneously articulating the nation as part of Western modernity, defined alternately as a historical period (beginning roughly in the 1500s), a set of aspirations (socio-economic, cultural, etc.), and/or a mode of experience. Marshall Berman famously described modernity as a continual process, a “maelstrom” driven by socioeconomic modernization or “the social processes that bring this maelstrom into being, and keep it in a perpetual state of becoming” (1988, 16). In Argentina, cultural modernisms such as indigenism came to constitute the “variety of visions and ideas that aim to make men and women the subjects as well as objects of modernization” (Berman Reference Berman1988, 16).Footnote 1

In the course of the twentieth century, modernist ballet and modern dance forms gained traction in Argentina in the context of cultural and economic debates that figured Europe and the United States as models; however, the problem remained of establishing these forms as Argentine. In his recent article “Racialized Dance Modernisms in Lusophone and Spanish-Speaking Latin America,” Jose Reynoso shows how twentieth-century “dance practices that combined ballet and modern dance with indigenous and Africanist expressive cultures participated in constructing hybrid national subjectivities that embodied both ‘culturally marked’ Latin American artistic practices and what is often assumed as ‘unmarked’ whiteness as representative of the ‘universal’” (2015, 392). In Argentina, ballet and modern dance signaled a universalized cultural advancement aligned with whiteness, while indigenous myths staged uniquely Latin American origins that held racial difference at a distance from the modern present. Caaporá and Consagración negotiated the “marked” (pre-Columbian themes) and the “unmarked” (ballet and modern dance vocabularies) toward different ends. While Caaporá strove to “Argentinize” European ballet at the turn of the century, Consagración marked the move to claim concert dance as Argentine at midcentury.

Caaporá is the earliest example of an Argentine ballet based on indigenous legends. Well-known modernist novelist Ricardo Güiraldes and painter Alfredo González Garaño developed the libretto and scenography for the ballet. They set about designing the work in the context of early twentieth-century nation-building projects that identified Europe as cultural, political, and economic referent. Caaporá's creators initiated a movement to “Argentinize” ballet by mixing “marked” pre-Columbian themes with “unmarked” ballet form, embodying calls by artists and intellectuals alike for artistic production to combine the indigenous and European. Caaporá prefigured three decades of emphasis (1926–1955) on pre-Columbian indigenous themes following the founding of the Colón Theatre Ballet in 1925, the oldest national ballet in South America.Footnote 2 European choreographers, many of whom had direct connections to the Ballets Russes, choreographed these national ballets. Just as Nijinsky's authorship was intended to do in the case of Caaporá, these choreographers secured the authenticity of the ballets’ European-ness. Despite the fact that it was never staged due to Nijinsky's failing health, Caaporá's lore looms large in Argentine dance history as the just barely missed opportunity to make one of global dance history's most enigmatic figures a protagonist in Argentina's local story.

Nearly fifty years later, celebrated Argentine choreographer Oscar Araiz drew on the by then established tradition of concert dance indigenism as he set out to create Consagración. Araiz's Consagración premiered under a military dictatorship that also privileged Western cultural models while strictly policing artistic production based on the enforcement of conservative Catholic values.Footnote 3 In the early 1960s, Araiz created a series of early works that synthesized his training in ballet and modern dance forms and featured pre-Columbian themes. He understands these works as precursors to the 1966 Consagración.Footnote 4 However, the final version of Consagración stripped the work of indigenism in favor of what the program note called the “global” genesis of mankind.Footnote 5 The universalized version of Consagración garnered critical acclaim and solidified Araiz's status as “an authentic luminary of Argentine choreography, if not the first in the entire national history of dance,” as one critic put it (Capelletti Reference Capelletti1967, emphasis mine).Footnote 6 The piece made this transition from local to universal themes at a critical moment in Argentine dance history. By the 1960s, the national ballet scene was well established, and modern dance had gained broader institutional support. In this climate, the dance community embarked on a project of valorizing a local concert dance tradition authored by Argentine-born choreographers. Critics identified Araiz as “authentic” Argentine dance luminary as part of the project of constructing concert dance as Argentine. Consagracion's move from the local to the universal instantiated a danced modernity no longer predicated on the marked staged in unmarked form by a European choreographer, but rather one characterized by the full citizenship of Argentine choreographers in universalism.

Caaporá and Consagración reveal how the management of Latin American racial difference was integral to Argentine modernity projects—socioeconomic as well as cultural—across the twentieth century. These works also emphasize the centrality of concert dance to modernity projects and debates. By examining these works side by side, this article provides insight into the past and present politics that shape the transnational circulation of modernist dance forms in the Global South. Through a focus on indigenism, it contributes to scholarship on the modernist negotiation of the marked and unmarked in Latin American dance as a strategy for staging—and transcending—the nation.Footnote 7

Caaporá: Danced Indigenism as Modernity

The development of Caaporá took place within the “maelstrom” of ongoing modernization projects that began in the nineteenth century. In the face of postindependence challenges to national unification, the oligarchical ruling class worked to overcome remaining colonial dependencies by combining the tenets of European liberalism with the promise of Argentina's national resources. Nation-building texts—most notably President Domingo Faustino Sarmiento's Facundo: civilación y barbarie (Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism, 1845)—dreamed of modernizing Argentina's urban center and populating its vast countryside pampas with white, disciplined, and hardworking Northern Europeans, especially German and British immigrants.Footnote 8 Urban development projects, particularly those organized around Argentina's 1910 centennial celebrations, “Europeanized” the city, a process that urban historian Adrián Gorelik locates between the turn of the century and 1930 (Reference Gorelik2004, 74). Argentine economic growth boomed during the early twentieth century, and by 1913 Argentina was one of the wealthiest nations per capita in the world.

These shifts set the stage for the national embrace of a dance company making waves on a global scale: Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. Argentine dance historians concur that the company's 1913 premiere was a wild success and maintain that the company set the standard of concert dance taste in turn-of-the-century Buenos Aires (Tambutti Reference Tambutti2000, 19; Falcoff Reference Falcoff2008, 234).Footnote 9 As Argentine dance historian Susana Tambutti explains, the success of the Ballets Russes was “an expression of the new wealth centered in Buenos Aires and of a ruling political class that cultivated a close relationship with the world of European culture” (Reference Tambutti2011b, 12).Footnote 10 Güiraldes and González Garaño saw the company in Paris as well as in Buenos Aires during its national debut and began to develop Caaporá following these encounters (Babino Reference Babino2010, 13).Footnote 11

In an effort to draft Nijinsky into Argentine dance history, Güiraldes adapted the Guaraní legend of Urutaú for Caaporá’s libretto. Argentine ethnographer and folklorist Juan Bautista Ambrosetti relayed this story of love, magic (the titular character is a god of dark magic personified by a tall bearded figure), and tribal conflict to Güiraldes.Footnote 12 Guaraní communities constituted a significant presence in Paraguay, northern Argentina, southern Brazil, and parts of Uruguay and Bolivia. When the Ballets Russes returned to Buenos Aires in September 1917, Güiraldes provided Nijinsky with a translated copy of the libretto manuscript, and they reportedly discussed the possibility of contracting Stravinsky to produce the musical score (Babino Reference Babino2010, 66).Footnote 13 While the ballet was never realized on the stage, plans for it reached the Buenos Aires public in May of the same year when González Garaño's paintings and set designs were exhibited as part of the Third Annual Watercolorists, Pastelists, and Etchers Salon (Babino Reference Babino and Bauzá2011, 101).Footnote 14

While it was never performed in Buenos Aires, Nijinsky's Le Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring, premiered May 29, 1913) inspired Caaporá's desired blend of pre-Columbian legend with experimental ballet choreography (Babino Reference Babino2010, 13). Nijinsky's Sacre depicted a series of rituals inspired by Russian folk rites and concluded with the sacrifice of a young woman. In one of the most highly circulated legends of twentieth-century dance history, the unfamiliarity of the work's choreographic aesthetics disturbed the audience to the point of rioting on the night of its Paris premiere. Scholarship on the Ballets Russes has traced how Sacre's aesthetic innovations marked the emergence of modernist ballet and, more broadly, the crises and contradictions of the modern age (Eksteins Reference Eksteins2000). Stravinsky's jagged and irregular rhythms and Nijinsky's weighted and angular choreography challenged familiar notions of beauty and grace attached to classical ballet.Footnote 15 As Lynn Garafola writes of the work, “the ballet has become synonymous with the very idea of modernity” (Reference Garafola1989, 51). Ramsay Burt argues that early discomfort with Sacre stemmed from the work's move away from symbolism toward expressive abstract movement, a shift experienced as “the loss of the familiar and its replacement with absences that reminded beholders of their own experience of modern living” (Reference Burt, Brooker, Gasiorek, Longworth and Thacker2011, 568).Footnote 16

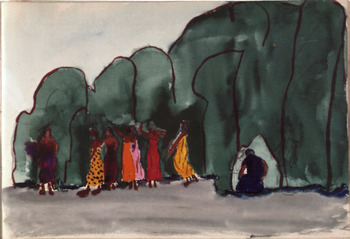

While Sacre staged an imagined Russian folk past as its choreography embodied the fragmentation of European modern life, it also functioned as a “portable model,” to borrow Michelle Clayton's turn of phrase, for Güiraldes and González Garaño (Reference Clayton2014, 38). In developing Caaporá, these artists aimed to insert the Argentine local past into a dance style that represented the latest cultural modernity (Clayton Reference Clayton2014, 38). As art historian María Elena Babino puts it, Caaporá arose from Güiraldes and González Garaño's desire for “the utopia of the discovery of the American through the prism of modernity” (Babino Reference Babino2010, 9).Footnote 17 González Garaño's forty-three Caaporá paintings offer visual documentation of this “discovery” of native bodies. The paintings, rendered in a bold palette emphasizing primary colors, depict the scenography and characters of the ballet. Indigenous warriors, clad in elaborate headdresses with intricate body paint, stand against abstract jungle backgrounds drawn in broad strokes of color. Caaporá, depicted as a towering figure with an orange, skull-like face, long beard, and elaborate red-feathered cape, cuts a particularly menacing figure. Several of the figures are in motion; in one image dark-skinned female bodies raise their arms toward the sky (Babino Reference Babino2010, 47). The collection also includes a series of sixteen “heads with tattoos” that depict “tribally” marked faces.

Photo 1. Caaporá. Painting by Alfredo González Garaño. Museo Gauchesco Ricardo Güiraldes, San Antonio de Areco, Argentina. Reproduced with permission of the Municipality of San Antonio de Areco.

Photo 2. Escenografía. Painting by Alfredo González Garaño. Museo Gauchesco Ricardo Güiraldes, San Antonio de Areco, Argentina. Reproduced with permission of the Municipality of San Antonio de Areco.

Caaporá's visual imagination of indigenous bodies in a high art context joined a growing conversation among Latin American artists and intellectuals that rejected nineteenth-century nation-building discourses that demanded the expulsion of indigenous strains in the interest of (white) development. Military initiatives in the 1830s and 1870s systematically set out to destroy indigenous cultures occupying the southern pampas (plains) and Argentine Patagonia. These projects operated on the logic of what Enrique Dussel terms the “myth of modernity,” or the colonial emancipatory logic in which the “uncivilized” and “barbaric” Other represents an obstacle to modernization (Dussel Reference Dussel and Barber1995, 136).Footnote 18 In his 1924 text Eurindia, influential Argentine intellectual Ricardo Rojas argues for the “utopic” rediscovery of pre-Columbian indigenous culture that Güiraldes and González Garaño envisioned. Rojas calls for a new period of cultural production in which indigenous elements blend seamlessly with European forms in the “truest” possible manifestation of Argentine criollo (Euro-Argentine) identity. Nearly a decade before the text's publication, Caaporá's vision of an indigenous legend set in vanguard motion literalized Rojas's aspirations for Argentine culture in/as ballet. With anticipated choreography by one of the most important innovators in Western dance history, Caaporá facilitated a “reencounter with what is one's own” (“reencuentro con lo propio”) that was both “authentically” Argentine and European (Babino Reference Babino2010, 15).

By imagining the indigenous presence in the ancient past (and to the far north of the country), Caaporá skirted the violence of the conquest and indigenous removal campaigns. However, suspending the indigenous body in the distant past ultimately reinforced the nineteenth-century notion that actual indigenous bodies and cultural practices are antithetical to (and should be absent from) the modern. Despite the brutal efficacy of removal campaigns, indigenous populations did and do remain, particularly in Argentina's northern provinces.Footnote 19 As in other strands of Latin American indigenism, Caaporá valorized pre-Columbian origins while reinforcing an evolutionary narrative of progress that absents indigenous bodies in the present.Footnote 20 Permanently assigned to an idyllic precolonial past, Caaporá's mythic indigenous bodies functioned to localize what would have been Nijinsky's choreography, a movement vocabulary and repertoire firmly tied to modernity in the minds of the cultural elite.

Güiraldes and González Garaño's intent to fuse modernist Russian ballet with a pre-Columbian legend played out repeatedly in the repertoire of the Colón Theater Ballet in the years from 1926 to 1955. The development of these works corresponded with what Tambutti understands as the “institutionalization” of the Ballets Russes within the Colón Theater (Reference Tambutti2011b, 12). The company returned to Buenos Aires in 1917 (when the plans for Caaporá were set), and from 1926 to 1927 Nijinsky's sister Bronislava Nijinska directed the newly formed national ballet (she returned briefly in 1933 and 1936). Additional artists with connections to the Ballets Russes circulated through the Colón Theater Ballet between 1925 and 1939, including Adolf Bolm, Boris Georgievich Romanoff, Elena Aleksandrovna Smirnova, Michel Fokine, Serge Lifar, and Ian Cieplinsky; these residencies and directorships further solidified the Ballets Russes legacy as an “official version of culture” (Tambutti Reference Tambutti2011b, 12).

These Ballets Russes-associated choreographers and other European born artists choreographed the Argentine indigenist ballets. Librettos adapted indigenous folktales (as in Caaporá) as well as contemporaneous poems and literary works based on pre-Columbian themes. Romanov's La flor del Irupé (Irupé's Flower, 1929), Margarete Wallmann's Panambí (1940), and Michel Borowski's El junco (The Reed, 1955) drew on Guaraní legends (Jaimes Reference Jaimes1960 and Tambutti Reference Tambutti2011a).Footnote 21 Cieplinsky's La leyenda del Uirapurú (The Legend of Uirapurú, 1934) imagined the pre-Columbian Amazon, while his El Pillán (1949) explored Mapuche mythology (Jaimes Reference Jaimes1960 and Tambutti Reference Tambutti2011a). Wallmann's Apurimac (1944) took up Incan themes, and Angelita Vélez's Altiplano (High Plain, 1947) depicted Andean indigenous rites (Jaimes Reference Jaimes1960 and Tambutti Reference Tambutti2011a).Footnote 22 While these ballets emphasized the indigenist strains of danced modernity, an equally robust number of ballets produced during this period evidenced an engagement with regional, rural, and/or folkloric topics.Footnote 23

Caaporá, and the indigenist ballet movement it initiated, established concert dance as a site of modernity vis-à-vis imagined indigenous bodies in balletic motion. At the turn of the century, danced modernity depended as much on the movement of imagined pre-Columbian bodies across the Colón Theater stage as it did on the circulation of dancers and choreographers affiliated with the Ballets Russes through the theater's halls. Emergent within modernization processes aimed at Europeanizing Argentina and articulating it within the development of Western modernity, Caaporá's pre-Columbian themes localized ballet without sacrificing the form's associations with unmarked universalism. While Caaporá inaugurated a strategy to “Argentinize” European ballet, fifty years later Oscar Araiz's La consagración de la primavera revised indigenism to establish concert dance as Argentine. Though separated by five decades, both works intersected with political projects similarly invested in equating Westernized modernity with Argentine national identity.

Oscar's Araiz's La consagración de la primavera: From Indigenism to Universalism

Oscar Araiz's La consagración de la primavera premiered at the San Martín Municipal Theater on July 4, 1966, at a critical moment in the development and professionalization of Argentine concert dance. The Friends of Dance Association (Asociación Amigos de la Danza, AADA) originally presented Consagración; a group of ballet and modern dancers and choreographers had founded this independent consortium in 1962 with the express purpose of professionalizing the Buenos Aires dance community, promoting the production of new work, and augmenting pedagogical and performance venues for ballet and modern dance. Araiz's training in the late 1950s and career development in the 1960s reflect the confluence of concert dance styles circulating through Argentina by the mid-twentieth century, particularly German expressionism and US modern dance. Araiz studied modern dance with influential figures including German-born Renate Schottelius and Dore Hoyer (both had connections to German expressionist dance pioneer Mary Wigman) and classical ballet with María Ruanova and former Ballets Russes dancer Tamara Grigorieva. Grigorieva settled in Argentina in 1944; through her Araiz had contact with the works of Michel Fokine and Léonide Massine.

Consagración's premiere took place within days of military general and de facto President Juan Carlos Onganía's June 28 coup d’état.Footnote 24 Known as the “Argentine Revolution,” the coup initiated socioeconomic modernization projects rooted in liberalism and waged a morality campaign in the name of rescuing the country's Western Catholic values from a supposedly degenerate, leftist youth culture. Onganía intensified the military's political control by suspending political parties and challenging university autonomy and labor movements. Anticommunist legislation and censorship—which specifically targeted intellectuals and artists—further tightened control on social expression. Despite this repressive climate, the institutional presence of concert dance increased throughout these volatile years.Footnote 25

In this climate of institutional support and increased political volatility, preoccupations around localizing Euro-American dance forms persisted. Consagración, like Caaporá, turned to indigenism to express a local, yet Westernized, modernity. In the early 1960s, Araiz choreographed two works, Ritos (Rites, 1961) and Cantata para Ámerica mágica (Cantata for Magical America, 1964), which explicitly staged pre-Columbian themes through hybridized modern and classical dance vocabularies. He identifies these works as precursors to Consagración. Araiz describes them as “rough drafts” and “sketches” in preparation for his engagement with Stravinsky's score.Footnote 26 Like the indigenist ballets discussed earlier, these pieces relied on music and costuming to invoke indigeneity; in Araiz's recollection, the costumes for Ritos were based on Mayan images.Footnote 27 Both works were set to and named after scores by prestigious contemporaneous Latin American composers. Ritos featured music by Mexican-born Carlos Chávez and Cantata was set to a score by Argentine-born Alberto Ginastera.Footnote 28 Both composers achieved recognition for blending classical and experimental musical styling with pre-Columbian influences. For Araiz, these two works fulfilled his desire to explore Latin American origins as a form of research leading up to choreography for Stravinsky's Sacre.

Araiz reports that Stravinsky's score had been an “obsession” since childhood though he initially knew nothing about the score's importance in global dance history (Falcoff Reference Falcoff1994, 32).Footnote 29 It would have been impossible for Araiz to engage with or replicate Nijinsky's choreography because there were no recordings or accessible recollections. Moreover, as a modernist choreographer, he was not interested in replicating previous iterations—either Nijinsky's or the other four well-known choreographic versions that existed at the time.Footnote 30 Instead, Araiz set out to engage the score's search for local origins, which for him as an Argentine choreographer required researching national heritage through pre-Columbian themes. Ritos and Cantata repeat the tradition initiated by Caaporá in which pre-Columbian themes localize unmarked movement forms associated with Western modernity.

Throughout the 1960s, several other choreographers engaged the indigenist themes that interested Araiz. In 1967, Felisa Guzman's American Indigenous Ballet took the stage of the General San Martín Municipal Theater, and several ballet and modern dance works presented by AADA featured pieces based on Argentine tango and rural themes.Footnote 31 The following year, Alfredo Rodríguez Arias's Love & Song, a musical comedy parody of folkloric music and dance's romanticized staging of the nation, premiered at the Di Tella Institute (“Viva el folklore” 1968).Footnote 32 Both Araiz and Ginastera were affiliated with this highly influential avant-garde cultural center (1958–1970) known for fomenting the development of Latin American conceptual art.Footnote 33 Like the Colón Theater before them, organizations including Di Tella and AADA fostered manifestations (and critiques) of indigenism as cultural modernity.

To move from the indigenist Ritos and Cantata to Consagración, Araiz shed the local. First, he replaced the Latin American scores with Stravinsky's internationally recognized music. Second, Consagración's nude leotard costumes replaced the colorful costuming of Ritos and Cantata. In addition, the program note for the 1966 premiere included a passage from French-German philosopher Georges Gusdorf's Myth and Metaphysics (Reference Gusdorf1953).Footnote 34 In abstract terms, the passage discusses the “festival” as a “global liturgy” that dramatizes “the great social game of transcendence, the recommencement of the Great Beginning. … The festival reestablishes the limit situation where order has been born of disorder: where chaos and cosmos adjoin together still.”Footnote 35 This passage links the work to a universalized drama of the origins of mankind as opposed to the particularisms of pre-Columbian culture.

The 1966 Consagración choreography and the “global liturgy” it purported to stage exist only in limited photographic documentation and Araiz's recollections. In the opening scene, a female dancer doubles over with one arm outstretched to the side and the other bent behind her back, fingers pointing to the sky. The dancer's forehead touches a voluminous skirt that seemingly extends the width and depth of the stage. Metaphorizing the title of the opening section, “Germinación” (“Germination”), dancers wearing flesh-toned bodysuits emerge from beneath the skirt, as if sprouting from the earth in the early days of spring. In the final scene depicting the sacrifice of the young woman, dancers lay on their stomachs in a semi circle, palms on the ground with fingers tips facing each other to create a sharp right angle at the elbow. Chins lifted above the ground, they stare at the Chosen One. Toes slightly turned in, the Chosen One stands with a contracted torso and gazes outward with a look of terror on her face as she confronts the foregone conclusion of her impending death.Footnote 36 Without any obvious cultural particularisms, the choreography combines modernist movement vocabulary, such as contractions and internally rotated postures, with Araiz's own visually rich innovations, including the “Germinación” skirt.

Photo 3. La consagración de la primavera. Choreographed by Oscar Araiz. Dancer: Estela Maris. Photographer: C. Bourquin. Buenos Aires, Argentina. 1966. Reproduced with the choreographer's permission.

By transcending the local in favor of universalist abstraction, Consagración garnered broad critical recognition as one of the most important works in national dance history. A 1966 review entitled “The Confirmation of a Talent and Lesson in Aesthetics at the Colón” (“Ratificación de un Talento y Lección de Estética en el Colón”) and published in the daily newspaper Clarín captured the euphoria surrounding the premiere of Araiz's work:

Araiz's concept is so deep as to present us with the vastest of possible dramas: humankind's existence as a species. … If any theater in the world had at their disposition the elements that make up the work—the dancers, orchestra, choreographer and director—it would not delay much in sending them abroad.Footnote 37 (“Ratificación de un Talento y Lección …” 1966)

The logic of the review reveled in the universalist intent of the choreography and equated export quality production with evidence of Argentine cultural modernity. It reasoned that in its successful presentation of the “vastest of possible dramas,” Consagración did choreographic justice to Stravinsky's iconic score and therefore was ready for the global stage. Whereas turn-of-the-century concert dance had become a site of modernity through the attempt to import Nijinsky's choreographic skills to Argentina, during the late 1960s the exportation of Argentine-born and trained professional dancers to the United States and Europe on performance tours became the requisite (and legitimizing) journey that signaled equality with global north dance production and translated into cultural capital at home.Footnote 38 In the years following the premiere of Consagración, Araiz fulfilled the aspirations articulated in the Clarín review, completing successful European and Canadian tours in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Upon his return to Buenos Aires, he premiered Araiz for Export (1974), a medley of works that included pieces originally presented in Buenos Aires now recompiled as “hits” from his European tours (“Araiz ensaya ‘Araiz For Export’” 1974). The title of the program exemplified and literalized the emphasis placed on international mobility as a sign of success.Footnote 39

However, Consagración not only signaled the latest danced modernity vis-à-vis its export-quality version of Euro-American dance forms, but also embodied a modernity that solidified concert dance as Argentine. The Clarín review states that Consagración was, “an exceptional case of expressive talent, it is one of the most important creations to have sprouted up in our midst” (“Ratificación de un Talento y Lección …” 1966).Footnote 40 In a similar vein, and as noted previously, music and dance critic Felix Carlos Capelletti (Reference Capelletti1967) argued that Consagración's modernist abstraction established Araiz as “an authentic luminary of Argentine choreography, if not the first in the entire national history of dance” (Capelletti Reference Capelletti1967).Footnote 41 Araiz as “authentic” Argentine dance luminary—the metaphorical Argentine Nijinsky—passed through the local to emerge as international artistic genius. The shift from Latin American indigenism in the Consagración “rough drafts” to “global liturgy” in the final version reflected the broader rise of conceptual art (experimental work concerned more with ideas than adherence to a particular form or style) promoted through production centers like the Di Tella Institute. However, Araiz's notion of Ritos and Cantata as preparatory exercises for Stravinsky's score signaled the persistent need to address the pre-Columbian local in order to secure an Argentine danced modernity also worthy of being recognized as universal on the global stage.Footnote 42 The Buenos Aires, ciudad secreta television episode that featured Araiz's commentary on Nijinsky's time in Argentina and his role in global dance history calls on Araiz's standing as international artistic luminary, a status established by the success of Consagración.

In light of Araiz's ascension as national luminary via Consagración's success, Foreign Relations Minister Nicanor Costa Méndez selected the work to display Argentine cultural sophistication to an audience of foreign dignitaries. On May 17, 1967, President Onganía and his wife María Emilia Green Urien attended a gala performance of Consagración at the Colón Theater in honor of the Japanese Prince Akihito and Princess Michiko's visit to Buenos Aires. On the evening of the gala and in the days to follow, Stravinsky's score once again found itself at the center of a theatrical scandal. Disturbed by the work's sexualized depictions and nude bodysuits, the president and his devoutly Catholic wife reportedly “left horrified” (“salió horrorizado”)—morals thoroughly offended (“Consagraciones” 1972 and Tucker Reference Tucker1971).Footnote 43 The following day, the Colón Theater administration contacted Araiz and notified him of the couple's “outrage” (“indignación”) over the performance (Araiz Reference Araizn.d.). In the same communication, Araiz also learned that the government strongly recommended the elimination of the piece from the Colón's repertoire—a move that effectively blacklisted it from other federally run performance spaces (Araiz Reference Araizn.d.). Ironically, the work that established concert dance as Argentine by way of export quality universalism had come into conflict with the military government's concept of Argentina as a Western, Catholic nation.

When Onganía and his wife took their seats in the Colón Theater's gilded presidential box to view the work, they were apparently unaware of Sacre's history—both its well-documented inspiration from Russian folk motifs and the riotous Parisian premiere. It is unlikely that they knew that Araiz's work formed part of a growing repertoire of choreographic interpretations of Stravinsky's score.Footnote 44 Costa Méndez's selection of Consagración for display to international dignitaries supports cultural critic Néstor García Canclini's assertion that Latin American elites’ embrace of modernist art in the twentieth century was articulated with national modernization projects (Reference García Canclini, Chiappari and López2005, 34). However, the work's unanticipated conflict with Onganía's self-proclaimed Western government—of which the work was intended to serve as aesthetic representation—signifies the failure of cultural modernism, in the eyes of the government, “to make men and women the subjects as well as object of modernization” where modernization was intimately linked to the state's policing of sexuality (Berman Reference Berman1988, 16). In a clash between Westernized cultural and national modernity, the national government disidentified from the staged “self” (Consagración) and the subsequently “embarrassing” representation of the nation to the Japanese royals.

The 1966 Clarín review (“Ratificación de un Talento y Lección …” 1966) compared Araiz's Consagración with French-born choreographer Maurice Béjart's 1959 version and declared the latter excessively sexual (Béjart is “extravagant and overflowing with sexuality”) while lauding Araiz's choreography's subtle sexuality.Footnote 45 The review's emphasis on the work's tasteful representation of sexual themes can be read as a veiled recognition of how the piece would read under Onganía's national mandate to perform conservative Christian values (“Ratificación de un Talento y Lección …” 1966). To invoke the choreographer's own turn of phrase, the choreography of the work was orgiastic but by no means pornographic.Footnote 46 Consagración's transgression in the eyes of Onganía's government—at the same moment that cultural critics heralded it as the arrival of a fully national dance modernity—demonstrates that socioeconomic modernization and cultural modernisms, while interconnected in their privileging of the West, came into conflict on the national stage. At midcentury, Consagración established concert dance as both fully Argentine and Western by passing through indigenism to achieve export quality universalism. However, despite celebrating the same European cultural values that the self-declared modernizing dictatorship promoted, the work conflicted with the government's parallel strain of conservative Catholic values. Consagración, then, not only grounded the claim to concert dance as Argentine, but also registered, through the Onganía scandal, a fracture in the formerly harmonious relationship between cultural modernisms and modernization. This departed from Caaporá's “Argentinization” of ballet vis-à-vis indigenism at the turn of the century, which established concert dance as a site of modernity precisely through its accordant embodiment of the oligarchical ruling class's Europeanized modernization project.

Ultimately, the 1967 scandal did not tarnish Araiz's career. The choreographer went on to actualize the role of luminary bestowed on him by Consagración's critical reception. He served as artistic director of the most recognized companies in Argentina, including the La Plata Argentine Theater Ballet, the San Martín Municipal Theater Contemporary Ballet, and the Colón Theater Ballet itself. Consagración first returned to the public stage during his directorship of the San Martín Municipal Theater Contemporary Ballet in 1970—this time with unitards that featured curving lines down the dancers’ limbs (A. C. 1970). The work did not reappear at the Colón Theater until 2000. Internationally, Araiz served as artistic director of the Geneva Grand Theater Ballet and worked with companies including the Winnipeg Ballet, Joffrey Ballet, and Paris Opera Ballet.

Araiz's Consagración and the work's precursors articulate the complexities of Argentine modernity in/as indigenist concert dance. In Buenos Aires of the late 1960s, Araiz's Consagración as danced modernity initially engaged imagined indigenous bodies and then moved toward universalism in the context of an expanding dance field and increasingly repressive political landscape. In its journey from Ritos and Cantata's indigenism to universalized critical acclaim, Consagración established concert dance as Argentine at the same time that the work's representation of sexuality challenged the moralistic ideals of Onganía's military regime's vision of modernity.

Dancing Indigenism in the Twenty-First Century

On December 26, 2009, floodwaters ravaged the Ricardo Güiraldes Museum in San Antonio de Areco, a small town seventy miles north of Buenos Aires. Museum workers and scholars struggled to rescue Güiraldes's papers, including the original libretto for Caaporá. According to Cecilia Smyth, the director of the museum at the time, the rescuers stayed so long that they needed to be saved by boat (Babino Reference Babino2010, 6). For Smyth, “what happened the morning of December 26 was a great blow for all of us who love national patrimony” (Babino Reference Babino2010, 6).Footnote 47 The near loss and dramatic archival rescue sparked renewed interest in Caaporá and generated urgency around the publication of the book Caaporá: Un ballet indígena en la modernidad (Caaporá: An Indigenous Ballet in Modernity), which contains reproductions of the libretto, Güiraldes’ handwritten manuscript, González Garaño's paintings, and critical commentary by Babino. Already in progress at the time of the flood, the text documents the natural disaster as a constitutive event in the ballet's history. The Caaporá volume employs the dramatic rescue scene as an introductory framing device, a move that not only mirrors the book's own recuperation of a ballet that never reached the stage, but also highlights the precariousness of archives and the often uneven processes by which pieces of the past are ushered into the realm of patrimony.

In addition to preserving the archival materials and making them available to a broader public, the publication of the text and images also coincided with the extensive festivities surrounding Argentina's May 2010 bicentennial celebrations. The Caaporá project itself had emerged following the 1910 Argentine Centennial festivities, which performed national identity at the height of Buenos Aires's Europeanization and set the stage for turn-of-the-century concert dance indigenism as modernity. Nearly one hundred years later, the book mitigated the “great blow” that the 2009 flood represented and joined a concurrent conversation around what constituted Argentine patrimony and identity—past, present, and future. Bicentennial-era concert dance works reflected on Argentine pasts and intercultural presents, particularly contemporary dance choreographer Gerardo Litvak's Criollo (2010). Problematizing the idea of a “national” dance form, Criollo blended contemporary dance with references to folkloric dance and music, techno, and cumbia villera (shantytown cumbia), the latter associated with racialized urban poor and migrants from Argentina's provinces, Bolivia, and Paraguay.Footnote 48 While Araiz's universalist Consagración had successfully established concert dance as Argentine in the 1960s, Criollo in 2010 recognized the need to grapple with tensions between Euro-American dance affiliations and racially marked cultural dance forms in the twenty-first century.

Government-sponsored bicentennial events as well as activist interventions brought indigenous rights into focus. In line with the broader populist project of President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner's government at the time, government events emphasized diversity, tolerance, and pan-Latin American belonging.Footnote 49 The Artistic-Historic Parade, an expansive historical pageant that featured more than 2,000 performers and represented “highlights” of Argentina's 200 years of independence, brought government sponsored events to a close on the day of the bicentennial. Directed by the well-known physical theater troupe Fuerza Bruta, the parade featured an opening scene in homage to Argentine indigenous populations. Like the concert dance works considered here, the parade staged indigenous cultures as pre-Columbian; however, the directors did construct the scene in dialogue with living indigenous communities and featured indigenous musicians and performers.

The day before the Artistic-Historic Parade, President Kirchner received representatives from indigenous delegations that had arrived in the capital as part of an “unofficial” event. Indigenous rights groups had joined together to coordinate a caravan of over 8,000 members of pueblos originarios (indigenous groups), and from May 12–20, volunteers marched from their respective provinces to the Buenos Aires's capital. The march, which adopted the slogan “for the path of truth, toward a plurinational state,” aimed to commemorate Argentine indigenous history, visibilize indigenous communities on the national stage, and call attention to the continued fight for land rights (Molinaro Reference Molinaro2012). While much work remains to be done in the struggle for indigenous rights in Argentina, the emphasis on the living presence of Argentine indigenous communities during government-sponsored bicentennial cultural events as well as in activist interventions like the caravan stands in contrast to the exclusively pre-Colombian status of these communities in concert dance works of the early to mid-twentieth century.

Litvak's Criollo therefore questioned the move of incorporating marked and unmarked movement vocabularies under the aegis of the “national” on the concert stage. The identification of Caaporá as part of the national patrimony in the context of these onstage and offstage negotiations of Argentine national identity and racial difference foregrounds the deeper historical entanglements of concert dance indigenism traced in this article. The aborted development of Caaporá as well as the success and scandal surrounding Araiz's Consagración are evidence of the repeated invocation of pre-Columbian bodies on the concert dance stage as modernity from the early to mid-twentieth century. Caaporá established concert dance as a site of Argentine modernity by localizing European ballet and thus echoing nation-building projects that situated Argentina within the universal march of Western modernity. Fifty years later, Consagración marked the transition to concert dance as itself Argentine. The work achieved export-quality universalism only after reckoning with and passing through Latin American racial difference in the context of a military dictatorship with a tight grip on cultural production. Reading these cases together not only tells the story of Argentine modernity, but also charts the twists and turns—literally and figuratively—that constitute the continual making of the global North/South and its others across concert stages, book pages, television screens, and archival encounters.