Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 A Marginal Centrist: Tzvetan Todorov and the French Intellectual Field

- 2 Todorov and Camus

- 3 The Enlightenment Redux: Autonomy in Todorov, Glucksmann, and Onfray

- 4 Todorov's Reading of Rousseau: A Heritage for Our Times?

- 5 Tzvetan Todorov's Enlightenment

- 6 Todorov and Bakhtin

- 7 Tzvetan Todorov and the Writing of History

- 8 Tzvetan Todorov and the Trials of History: A Dissenting Voice

- 9 European Integration and the Cultural Cold War: Todorov and Denis de Rougemont

- 10 Tzvetan Todorov on Totalitarianism, Scientism, and Utopia

- 11 Tzvetan Todorov's Political Philosophy

- 12 Interview with Tzvetan Todorov

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

12 - Interview with Tzvetan Todorov

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 April 2020

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 A Marginal Centrist: Tzvetan Todorov and the French Intellectual Field

- 2 Todorov and Camus

- 3 The Enlightenment Redux: Autonomy in Todorov, Glucksmann, and Onfray

- 4 Todorov's Reading of Rousseau: A Heritage for Our Times?

- 5 Tzvetan Todorov's Enlightenment

- 6 Todorov and Bakhtin

- 7 Tzvetan Todorov and the Writing of History

- 8 Tzvetan Todorov and the Trials of History: A Dissenting Voice

- 9 European Integration and the Cultural Cold War: Todorov and Denis de Rougemont

- 10 Tzvetan Todorov on Totalitarianism, Scientism, and Utopia

- 11 Tzvetan Todorov's Political Philosophy

- 12 Interview with Tzvetan Todorov

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

Summary

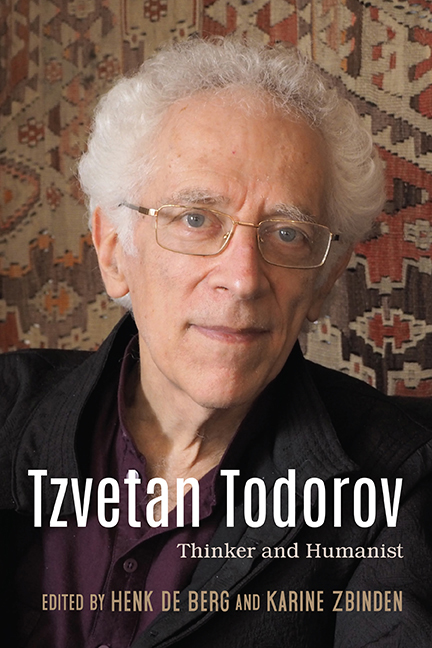

THE INTERVIEW WITH Tzvetan Todorov reproduced below, one of the last before his death on February 7, 2017, was conducted in Paris on March 5, 2016. Short editorial glosses have been added in square brackets, while longer comments and literature references are provided in the notes. Bibliographical details of Todorov's own texts mentioned in the interview can be found in the introduction to this volume.

The Enlightenment

Of all the periods of the history of ideas, the Enlightenment has inspired you most. Why is this era so important? It is important for me, as it is for all of us, because it is the era that gave shape to our modern identity. It is the time when the small changes that had been accumulating since the Renaissance started to bring forth radical change. We entered fully into modernity. So this period of mutation, of transition, is particularly interesting because we can see the past and the present interacting and thus casting light on each other.

You disagree with Horkheimer's and Adorno's Dialectic of Enlightenment, which propounds that, in the wake of the Enlightenment and the industrial revolution, reason turned against itself and, having become inextricably linked to capitalism and science, is today little more than blinkered “instrumental reason.”

I do not share their point of view, but I think I need to make something clear from the outset, because it will be relevant for the other questions you may ask me: I do not see myself as a philosopher. I think of myself more as a historian—a historian of ideas, yes, with opinions, defending particular positions, but not conversing with the great philosophers of the past. Coming back to the actual question, I also see the dark side of the Enlightenment. There are some aspects of the Enlightenment that for me seem to be its shadow, a potential threat. But I don't have the same pessimistic view as Horkheimer and Adorno, who during the Second World War observed a kind of global destruction of the European spirit, of the path of European history, as if everything had to lead to totalitarianism, which dominated political and public life in Europe at that time. I feel that they overemphasize a particular, existing but not unavoidable, historical development.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Tzvetan TodorovThinker and Humanist, pp. 236 - 258Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2020