Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Illustrations

- Troubling Images: An Introduction

- 1 The Trajectory and Dynamics of Afrikaner Nationalism in the Twentieth Century: An Overview

- One Assent and Dissent Through Fine Art and Architecture

- Two Sculptures on University Campuses

- Three Photography, Identity and Nationhood

- Four Deploying Mass Media and Popular Visual Culture

- Contributor Biographies

- Index

5 - ‘It’s Not Even Past’: Dealing with Monuments and Memorials on Divided Campuses

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 March 2020

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Illustrations

- Troubling Images: An Introduction

- 1 The Trajectory and Dynamics of Afrikaner Nationalism in the Twentieth Century: An Overview

- One Assent and Dissent Through Fine Art and Architecture

- Two Sculptures on University Campuses

- Three Photography, Identity and Nationhood

- Four Deploying Mass Media and Popular Visual Culture

- Contributor Biographies

- Index

Summary

INTRODUCTION

The urgency of symbolic reparation was brought to public attention in a very dramatic manner at the University of Cape Town (UCT) in 2015. Student protestors demanded, and shortly thereafter achieved, the removal of the bronze statue of British imperialist Cecil John Rhodes from its prominent perch on the main campus. Activists would, however, make the point repeatedly that the attack on the Rhodes statue was about something much bigger – a general sense of disaffection with, and alienation from, white institutions, in this case UCT (Ngcaweni and Ngcaweni 2018).

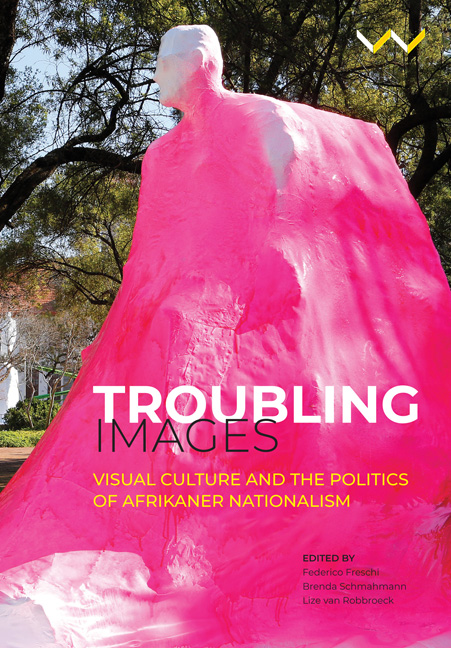

In many ways, the focus on Rhodes was a strategic masterstroke. The statue was a visible and tangible representation of black student discontent with the institutional cultures and practices of former white universities. The statue could therefore be lifted and removed in full sight, offering a political spectacle that demonstrated student power even as it symbolised the uprooting of a concrete symbol of whiteness. It should be no surprise, therefore, that the attack on the statue spread quickly to other former white campuses around the country, from the statue of King George V on the campus of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) to the monument of President Steyn at the University of the Free State (UFS).

In real time, images of statues defaced, toppled or removed were carried through social media platforms across the country and around the world, thereby boosting the student cause as well as mobilising further activism around these visible representations of South Africa's colonial and apartheid past (Jansen 2017). In the minds of activists, these physical attacks on statues were a starting point for deeper changes to white institutions, from addressing the paucity of black professors to eliminating the Eurocentrism of the resident curriculum.

It would be a mistake, however, to think that student discontent started with the UCT student Chumani Maxwele pouring human excrement on the Rhodes statue; in fact, activism around race, culture and the curriculum at UCT began much earlier, when postgraduate students protested the closure of African Studies as an independent department, and when Senate decided to stop using race as the only measure of disadvantage in decisions on student admissions (UCT 2014). The word ‘decolonisation’ was used during these protests, long before the discontent boiled over in 2015.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Troubling ImagesVisual Culture and the Politics of Afrikaner Nationalism, pp. 119 - 139Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2020