Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue: Emazambaneni: The land of terror

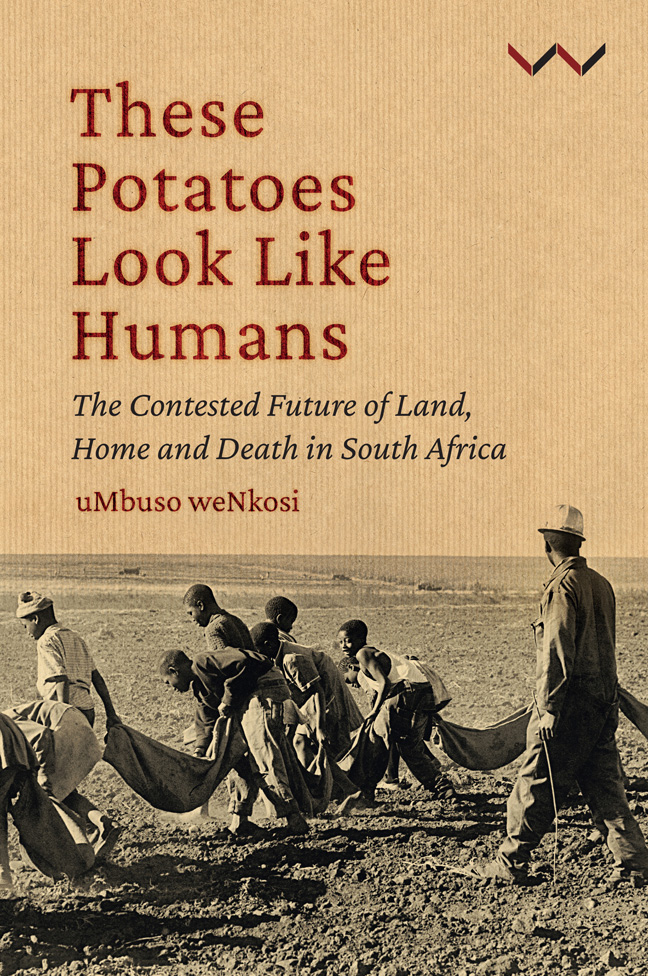

- 1 The spectre of the human potato

- 2 Whose eyes are looking at history?

- 3 Bethal, the house of God

- 4 Violence: The white farmers’ fears erupt

- 5 These eyes are looking for a home

- 6 Bethal today

- 7 Our eschatological future

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

5 - These eyes are looking for a home

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 March 2024

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue: Emazambaneni: The land of terror

- 1 The spectre of the human potato

- 2 Whose eyes are looking at history?

- 3 Bethal, the house of God

- 4 Violence: The white farmers’ fears erupt

- 5 These eyes are looking for a home

- 6 Bethal today

- 7 Our eschatological future

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

I believe there is no society of any kind in the Colonies, nothing that I would call society; so when you have made your fortune you must come back and assert yourself in London.

— Oscar WildeThe starting point in defining the ontological category of being Black is usually from its negative – that is to say, from what being Black is not – to arrive at a defence of what it is. It is a difficult definition to make. The negative ontological categories show a people wounded in time. For a Black person, time is a shifting terrain that the condition of dispossession helps to situate. The wound of Black people binds them collectively and negatively into a future where they are again victims of a past that did not see them as human. This negative ontological category makes the subject of Blackness indeterminate when the future is mentioned.

Is there a collective state of being that binds all Black people in South Africa under the sociological category ‘a society’? I provide a sociological reading of dispossession to answer this question, drawing on a theoretical standpoint which positions the eye as an ethical tool for understanding history. At the same time, I move from the framework of the optical as ethical to look at ‘society’. The history of dispossession has been centred on white society and its fears of the future projected onto the negative ontological category of Black. In this pursuit, I let go of the Manicheanism already inherited from those who wrote of the ‘black’ or the ‘white’ because I have already constructed the Manicheanism. However, in proceeding with the optical I use my eye not only as an eye belonging to the wounded collective, but as an eye concerned with the future, an eye of the Black intellectual. I have positioned dispossession as a construction of the future that maintains this negative ontological category of a Black person who has been wandering to nowhere.

My concern is not only to offer a different understanding of the question of land in South Africa; my eye is also an eye of a haunted being, who is not innocent in the reading of history, haunted by the dead (like Gogo Mshanelo, whom we met in chapter 2). Unlike Mshanelo, I cannot provide the dead with the peace and justice that they need.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- These Potatoes Look Like HumansThe Contested Future of Land, Home and Death in South Africa, pp. 97 - 114Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2023