Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue: Emazambaneni: The land of terror

- 1 The spectre of the human potato

- 2 Whose eyes are looking at history?

- 3 Bethal, the house of God

- 4 Violence: The white farmers’ fears erupt

- 5 These eyes are looking for a home

- 6 Bethal today

- 7 Our eschatological future

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

7 - Our eschatological future

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 March 2024

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue: Emazambaneni: The land of terror

- 1 The spectre of the human potato

- 2 Whose eyes are looking at history?

- 3 Bethal, the house of God

- 4 Violence: The white farmers’ fears erupt

- 5 These eyes are looking for a home

- 6 Bethal today

- 7 Our eschatological future

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

There are people who are like tigers thirsting for blood. Anyone who has once experienced this power, this unlimited mastery of the body, blood and soul of a fellow man made of the same clay as himself, a brother in the law of Christ, anyone who has experienced the power and full licence to inflict the greatest humiliation upon another creature made in the image of God will unconsciously lose the mastery of his own sensations. Tyranny is a habit; it may develop, and it does develop at last, into a disease.

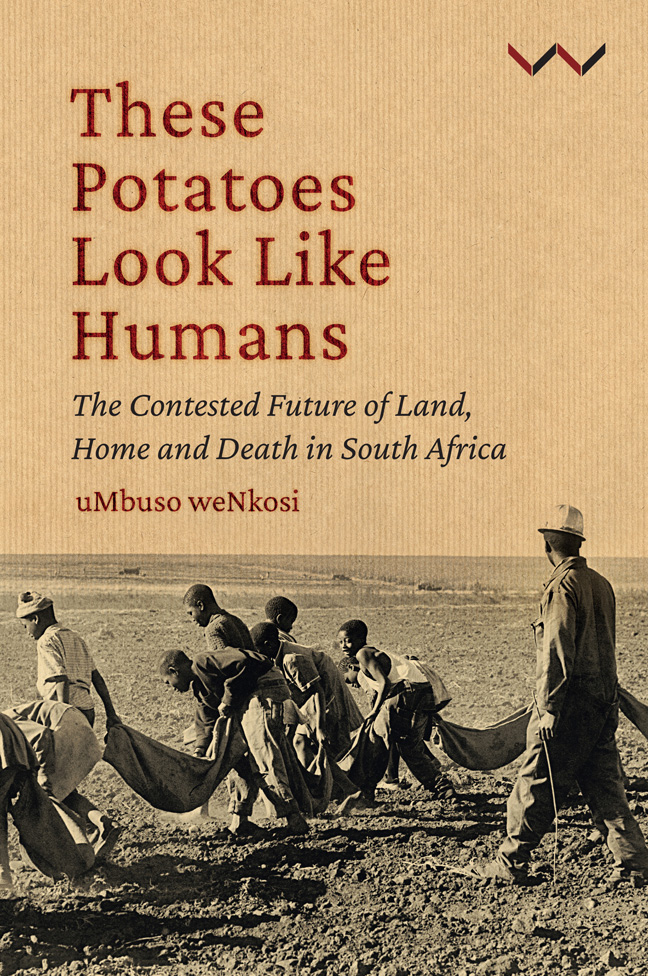

— Fyodor DostoevskyThe creation of large hectares of farmland in South Africa involved the brutal annihilation of people not considered human. Fyodor Dostoevsky argues that anyone who has killed will lose mastery of their sensations, and I have argued that they will have iqunga, which is an urge to continue to kill. In focusing on Bethal, I linked the history of dispossession to how the white society in South Africa was suffering from anxiety related to how they deprived Black people of their land. Dispossession is not a complete act since the dispossessor fears that those who get removed from the land will contest it in future. That is the futurity of violence – it aims to ensure that the future of land is not contested. This futurity is embedded in the problem of ontology; philosophically, ontology, or being in the world, is claiming the self through violence. The claim of the self is about being recognised by the Other through the use of violence, ‘through a life-and-death struggle’. This is the insatiability of violence in ontology.

Through looking at dispossession, I have, firstly, argued that Black people had to confront ontological nowhereness, which is about dealing with the state of being homeless. The state of being homeless is related to how the white society claimed its being in the world – that white people are superior. I showed the limits of this superiority in that it has to confront the unknown future. My argument is that the violence of ontology in white society reflects their anxiety about the future. In positing that dispossession impacted both Black and white people as an ontological problem, I aimed to show the limits of ontological violence.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- These Potatoes Look Like HumansThe Contested Future of Land, Home and Death in South Africa, pp. 131 - 140Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2023