Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction

- The Curious Production and Reconstruction of Oxford, Bodleian Library, Junius 85 and 86

- ‘Through a glass darkly’, or, Rethinking Medieval Materiality: A Tale of Carpets, Screens and Parchment

- Distortion, Ideology, Time: Proletarian Aesthetics in the Work of Lionel Britton

- Shakespeare and Korea: Mutual Remappings

- Dictionary Distortions

- Where Do Indigenous Origin Stories and Empowered Objects Fit into a Literary History of the American Continent?

- Distortion in Textual Object Facsimile Production: A Liability or an Asset?

- The Uncanny Reformation: Revenant Texts and Distorted Time in Henrician England

- The Presence of the Book

- Index

Distortion, Ideology, Time: Proletarian Aesthetics in the Work of Lionel Britton

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 August 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction

- The Curious Production and Reconstruction of Oxford, Bodleian Library, Junius 85 and 86

- ‘Through a glass darkly’, or, Rethinking Medieval Materiality: A Tale of Carpets, Screens and Parchment

- Distortion, Ideology, Time: Proletarian Aesthetics in the Work of Lionel Britton

- Shakespeare and Korea: Mutual Remappings

- Dictionary Distortions

- Where Do Indigenous Origin Stories and Empowered Objects Fit into a Literary History of the American Continent?

- Distortion in Textual Object Facsimile Production: A Liability or an Asset?

- The Uncanny Reformation: Revenant Texts and Distorted Time in Henrician England

- The Presence of the Book

- Index

Summary

Lionel Britton (1887–1971) was the son of Richard Britton, an eventually bankrupted and not fully qualified solicitor who died of tuberculosis in 1894 when Britton was seven, and Ira Britton, who supplemented the family income as a boarding-house keeper and briefly remarried. Despite the professional promise that might have bestowed a safely bourgeois existence from his father's side, Lionel Britton largely grew up with his maternal grandparents in Redditch and left home for Birmingham, where he lived on a loaf of bread for a week before heading to London. His family did not have the means to pay for his interest in learning and education – he attended a national school – and Britton was an errand boy for a greengrocer's and then a bookshop. He was imprisoned for over a year as a conscientious objector during the First World War and gained employment working for the Incorporated Society of British Advertisers in the 1920s. He unsuccessfully applied for Soviet citizenship in the late 1910s but is also notable for the fact that, unlike some leading intellectual figures in Britain during the 1920s and 1930s, he recognised that the Soviet Union was a dictatorship and not a worker's paradise.

His relatively brief but brilliant literary flourishing at the end of the 1920s and early 1930s resulted in a novel – Hunger and Love (1931) – and the plays Brain: A Play of the Whole Earth (1930), Spacetime Inn (1932) and Animal Ideas: A Dramatic Symphony of the Human in the Universe (1935). Hunger and Love was a Bildungsroman of a kind, but supplants the normative alignment of individual becoming and socialisation with a shift towards a collective, communal temporality at odds with bourgeois modernity. Spacetime Inn and Brain might be deemed science-fiction plays, though such a designation does not do justice to how each again disorders time and history. The former is set in the eponymous hostelry where two working-class Cockneys, Bill and Jim, win the sweepstake and traverse the dimensions of spacetime to join the company of fellow guests such as Shakespeare, George Bernard Shaw, Dr Johnson, Karl Marx, Napoleon, Queen Victoria, The Queen of Sheba and Eve.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

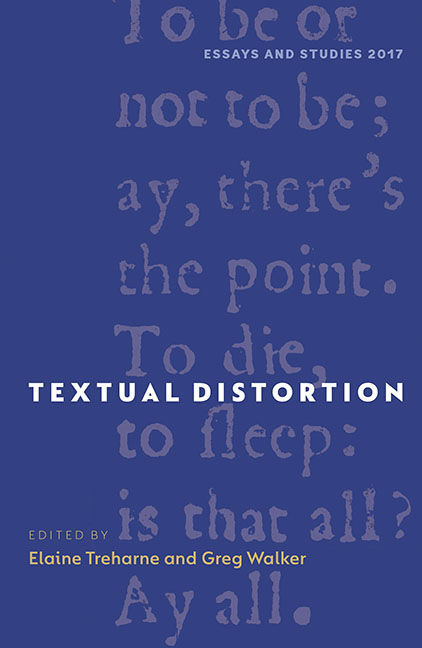

- Textual Distortion , pp. 47 - 71Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2017