Book contents

Chapter 2 - Representing Sara Baartman in the New Millennium

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 April 2021

Summary

In late February 2018, controversy erupted around Willie Bester's sculpture of Sara Baartman, located in the main library of the University of Cape Town. The statue had been clothed in a kanga and headscarf, but a storm of debate and media attention arose when a university librarian, a white man originally from the United States, removed these garments. Globally, but especially in South Africa, the figure of Sara Baartman continues to surface morbidly in frenzied efforts by various groups to define themselves. These efforts are often emphatic about the project of defending Sara and telling her ‘true’ story. But what does this mean? In the following exchange, Zoë Wicomb and Desiree Lewis deal critically with the 2018 enrobing and disrobing, and explore what it means to represent Sara Baartman.

Desiree: Reading revisionist work on Sara Baartman since the start of the millennium, I’ve been struck by two main trajectories: one is evident in scholarly work by Pamela Scully and Rachel Holmes. Their projects aim to ‘set the record straight’ by inserting Sara as an agential human being. I can see that their work sets out to transcend traditions that focus only on Sara Baartman's violation, traditions that dominate critical, artistic and scholarly work from the second half of the twentieth century. So their revisionist turn seems to involve refuting the determinist model of Baartman (only) as a victim of history and demonstrating that she made choices: deciding for herself to go to England, for example.

These are respected historians and biographers. Yet I’ve been struck by the patent fictionalising in their studies, as well as the naivety of their projects as acts of representation. In Pamela Scully and Clifton Crais's Sara Baartman and the Hottentot Venus: A Ghost Story and a Biography, for example, the Bildungsroman form credits Baartman with the power of personal growth, mobility, choices in relationships, and so on. Baartman's story is also told using narrative conventions and styles reminiscent to me at times of Charles Dickens, or more contemporary potboiler mysteries.

The other trend, often followed by those who claim a marginality similar to Baartman’s, also fixates on telling her true story – yet refuses to acknowledge how pasts are always shaped by presents, how writers’ and activists’ retrospective sense-making inevitably colours storytelling about figures in the past.

- Type

- Chapter

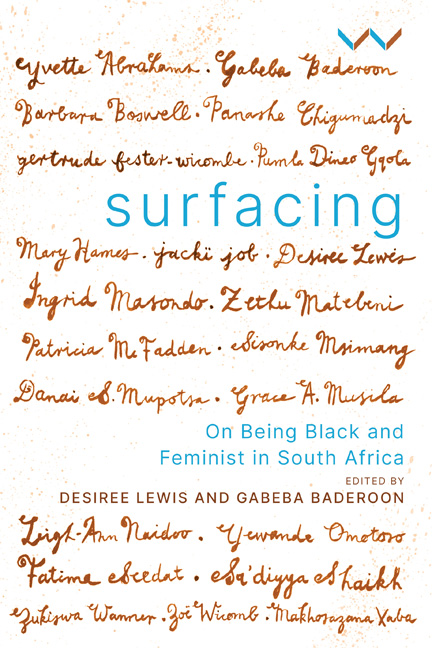

- Information

- SurfacingOn Being Black and Feminist in South Africa, pp. 28 - 46Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2021