Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Notes on contributors

- Preface

- A note on transliteration

- Glossary

- 1 Joseph Stalin: power and ideas

- 2 Stalin as Georgian: the formative years

- 3 Stalin as Commissar for Nationality Affairs, 1918–1922

- 4 Stalin as General Secretary: the appointments process and the nature of Stalin's power

- 5 Stalin as Prime Minister: power and the Politburo

- 6 Stalin as dictator: the personalisation of power

- 7 Stalin as economic policy-maker: Soviet agriculture, 1931–1936

- 8 Stalin as foreign policy-maker: avoiding war, 1927–1953

- 9 Stalin as Marxist: the Western roots of Stalin's russification of Marxism

- 10 Stalin as Bolshevik romantic: ideology and mobilisation, 1917–1939

- 11 Stalin as patron of cinema: creating Soviet mass culture, 1932–1936

- 12 Stalin as producer: the Moscow show trials and the construction of mortal threats

- 13 Stalin as symbol: a case study of the personality cult and its construction

- 14 Stalin as the coryphaeus of science: ideology and knowledge in the post-war years

- Index

13 - Stalin as symbol: a case study of the personality cult and its construction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 November 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Notes on contributors

- Preface

- A note on transliteration

- Glossary

- 1 Joseph Stalin: power and ideas

- 2 Stalin as Georgian: the formative years

- 3 Stalin as Commissar for Nationality Affairs, 1918–1922

- 4 Stalin as General Secretary: the appointments process and the nature of Stalin's power

- 5 Stalin as Prime Minister: power and the Politburo

- 6 Stalin as dictator: the personalisation of power

- 7 Stalin as economic policy-maker: Soviet agriculture, 1931–1936

- 8 Stalin as foreign policy-maker: avoiding war, 1927–1953

- 9 Stalin as Marxist: the Western roots of Stalin's russification of Marxism

- 10 Stalin as Bolshevik romantic: ideology and mobilisation, 1917–1939

- 11 Stalin as patron of cinema: creating Soviet mass culture, 1932–1936

- 12 Stalin as producer: the Moscow show trials and the construction of mortal threats

- 13 Stalin as symbol: a case study of the personality cult and its construction

- 14 Stalin as the coryphaeus of science: ideology and knowledge in the post-war years

- Index

Summary

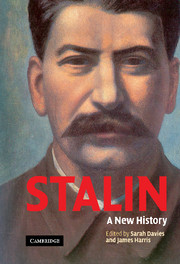

In 1956, N. S. Khrushchev denounced Stalin's cult of personality as a psychosis having little connection to Soviet ideology as a whole. Arguing that the cult ‘took on such monstrous proportions because Stalin himself supported the glorification of his own person, using all available methods,’ Khrushchev illustrated his contention with reference to Stalin's official Short Biography. Few since have questioned this characterisation of the cult, in part because of the difficulty of reconciling the promotion of a tsar-like figure with the egalitarian ideals of Soviet socialism.

Although the cult of personality certainly owed something to Stalin's affinity for self-aggrandisement, modern social science literature suggests that it was designed to perform an entirely different ideological function. Personality cults promoting charismatic leadership are typically found in developing societies where ruling cliques aspire to cultivate a sense of popular legitimacy. Scholars since Max Weber have observed that charismatic leadership plays a particularly crucial role in societies that are either poorly integrated or lack regularised administrative institutions. In such situations, loyalty to an inspiring leader can induce even the most fragmented polities to acknowledge the authority of the central state despite the absence of a greater sense of patriotism, community, or rule of law.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- StalinA New History, pp. 249 - 270Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2005

- 7

- Cited by