Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Notes on contributors

- Preface

- A note on transliteration

- Glossary

- 1 Joseph Stalin: power and ideas

- 2 Stalin as Georgian: the formative years

- 3 Stalin as Commissar for Nationality Affairs, 1918–1922

- 4 Stalin as General Secretary: the appointments process and the nature of Stalin's power

- 5 Stalin as Prime Minister: power and the Politburo

- 6 Stalin as dictator: the personalisation of power

- 7 Stalin as economic policy-maker: Soviet agriculture, 1931–1936

- 8 Stalin as foreign policy-maker: avoiding war, 1927–1953

- 9 Stalin as Marxist: the Western roots of Stalin's russification of Marxism

- 10 Stalin as Bolshevik romantic: ideology and mobilisation, 1917–1939

- 11 Stalin as patron of cinema: creating Soviet mass culture, 1932–1936

- 12 Stalin as producer: the Moscow show trials and the construction of mortal threats

- 13 Stalin as symbol: a case study of the personality cult and its construction

- 14 Stalin as the coryphaeus of science: ideology and knowledge in the post-war years

- Index

11 - Stalin as patron of cinema: creating Soviet mass culture, 1932–1936

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 November 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Notes on contributors

- Preface

- A note on transliteration

- Glossary

- 1 Joseph Stalin: power and ideas

- 2 Stalin as Georgian: the formative years

- 3 Stalin as Commissar for Nationality Affairs, 1918–1922

- 4 Stalin as General Secretary: the appointments process and the nature of Stalin's power

- 5 Stalin as Prime Minister: power and the Politburo

- 6 Stalin as dictator: the personalisation of power

- 7 Stalin as economic policy-maker: Soviet agriculture, 1931–1936

- 8 Stalin as foreign policy-maker: avoiding war, 1927–1953

- 9 Stalin as Marxist: the Western roots of Stalin's russification of Marxism

- 10 Stalin as Bolshevik romantic: ideology and mobilisation, 1917–1939

- 11 Stalin as patron of cinema: creating Soviet mass culture, 1932–1936

- 12 Stalin as producer: the Moscow show trials and the construction of mortal threats

- 13 Stalin as symbol: a case study of the personality cult and its construction

- 14 Stalin as the coryphaeus of science: ideology and knowledge in the post-war years

- Index

Summary

At his two well-known meetings with writers at Gorky's home in October 1932, Stalin encouraged his audience to focus on writing plays, which he believed to be most accessible to workers: ‘Poems are good. Novels are even better. But at the moment more than anything we need plays’. His hierarchy did not include films and screen-writing, for, despite Lenin's sanctification of cinema as ‘the most important of the arts’, at this juncture it was less highly esteemed by Stalin, and many others in the Soviet Union. From January 1932 until February 1933 the status of the organisation responsible for the Soviet film industry, Soiuzkino, was merely that of part of the Commissariat of Light Industry. The political leadership complained constantly that Soviet cinema was not fulfilling its potential. Audiences preferred imported films. Other artists tended to regard the young art of cinema as inferior to their own well-established fields. By the mid-1930s, however, the situation had changed dramatically. In 1935, when informed that some cinemas in Moscow had been taken over for use as theatres, Stalin was appalled that as a consequence ‘the art most popular amongst the masses’ could not be exhibited so widely. In the same year, film-workers were feted by the party and government at a lavish anniversary celebration which resembled to one contemporary ‘an Academy Award evening, without the jokes’.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

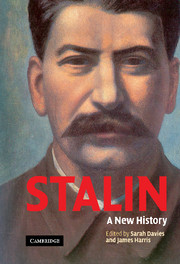

- StalinA New History, pp. 202 - 225Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2005