Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1 The Ends of First Sf: Pioneers as Veterans

- 2 After the New Wave: After Science Fiction?

- 3 Beyond Apollo: Space Fictions after the Moon Landing

- 4 Big Dumb Objects: Science Fiction as Self-Parody

- 5 The Rise of Fantasy: Swords and Planets

- 6 Home of the Extraterrestrial Brothers: Race and African American Science Fiction

- 7 Alien Invaders: Vietnam and the Counterculture

- 8 This Septic Isle: Post-Imperial Melancholy

- 9 Foul Contagion Spread: Ecology and Environmentalism

- 10 Female Counter-Literature: Feminism

- 11 Strange Bedfellows: Gay Liberation

- 12 Saving the Family? Children's Fiction

- 13 Eating the Audience: Blockbusters

- 14 Chariots of the Gods: Pseudoscience and Parental Fears

- 15 Towers of Babel: The Architecture of Sf

- 16 Ruptures: Metafiction and Postmodernism

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

13 - Eating the Audience: Blockbusters

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1 The Ends of First Sf: Pioneers as Veterans

- 2 After the New Wave: After Science Fiction?

- 3 Beyond Apollo: Space Fictions after the Moon Landing

- 4 Big Dumb Objects: Science Fiction as Self-Parody

- 5 The Rise of Fantasy: Swords and Planets

- 6 Home of the Extraterrestrial Brothers: Race and African American Science Fiction

- 7 Alien Invaders: Vietnam and the Counterculture

- 8 This Septic Isle: Post-Imperial Melancholy

- 9 Foul Contagion Spread: Ecology and Environmentalism

- 10 Female Counter-Literature: Feminism

- 11 Strange Bedfellows: Gay Liberation

- 12 Saving the Family? Children's Fiction

- 13 Eating the Audience: Blockbusters

- 14 Chariots of the Gods: Pseudoscience and Parental Fears

- 15 Towers of Babel: The Architecture of Sf

- 16 Ruptures: Metafiction and Postmodernism

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

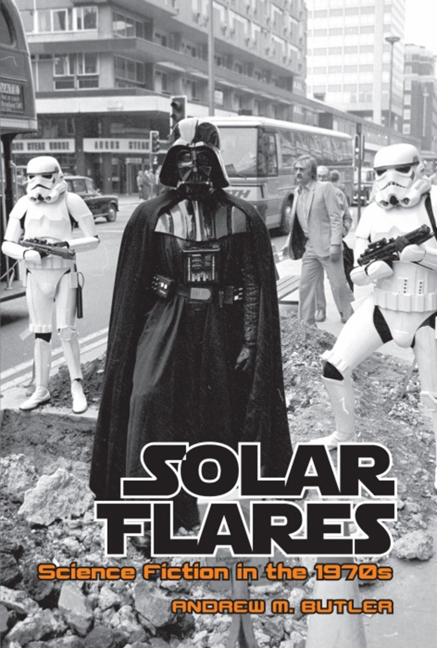

Thomas Schatz's assertion that the blockbuster film was apolitical is misleading. At best, such films appealed to a range of audiences of varying opinions and offered various readings; at worst, they upheld the dominant ideology's status quo. Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977) performed a political role of recuperating the American Dream in the aftermath of Vietnam and the realignment of the Cold War from one proxy campaign to another. Later, Ronald Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative was to be nicknamed Star Wars, and Vietnam veteran Colonel Oliver North called himself a Jedi knight during the Iran-Contra affair that broke in 1986. The blockbuster films had their political uses. They also often centred upon broken or dispersed families, with the narrative pointing towards the creation or recreation of a social unit, and they especially explored father–son relations. With the exception of Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back (Irvin Kershner, 1980), which ends with a cliffhanger, the endings were upbeat and reassuring, rather than amphicatastrophic. This chapter will consider the films THX 1138 (1971) and the Star Wars trilogy, the first two Superman films and Flash Gordon (Mike Hodges, 1980).

The blockbuster movie had emerged in the 1950s and 1960s, as part of Hollywood's fightback against the haemorrhaging of audiences to television, but took a new form in the mid-1970s as producers targeted youth and family audiences. The blockbuster ‘will excite you, expose you to something never before experienced, […] prick up your ears and make your eyes bulge out in awe’ (Stringer 2003: 5). Awe and the sublime are central to the experience of blockbuster cinema, as the audience is taken on a rollercoaster ride of action-adventure, punctuated with stunts and special effects. The discourse around the films is as much of processed shots and new production technology as it is of actors and gossip – the use of blue and green screens, matte work, rotoscope, computer-controlled camera movements and beyond became part of the publicity materials. The special effect, paradoxically, is not just there to represent the unfilmable, but to announce its own status as effect, to undermine its invisibility.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Solar FlaresScience Fiction in the 1970s, pp. 181 - 191Publisher: Liverpool University PressPrint publication year: 2012