Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Shakespeare in English, English in South Africa

- Chapter 2 ‘Through Shakespeare's Africa’: ‘Terror and murder’?

- Chapter 3 Tony's Will: Titus Andronicus in South Africa, 1995

- Chapter 4 Begging the questions: Producing Shakespeare for post-apartheid South African schools

- Chapter 5 English and the African Renaissance

- Chapter 6 Shakespeare and the coconuts

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Shakespeare in English, English in South Africa

- Chapter 2 ‘Through Shakespeare's Africa’: ‘Terror and murder’?

- Chapter 3 Tony's Will: Titus Andronicus in South Africa, 1995

- Chapter 4 Begging the questions: Producing Shakespeare for post-apartheid South African schools

- Chapter 5 English and the African Renaissance

- Chapter 6 Shakespeare and the coconuts

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Ingrid de Kok's poem ‘Merchants in Venice’ addresses the relationship between rich, established Europe and its so-called high culture, and poor, entrepreneurial Africa. The poem offers ways to read the presence of Africans in this famous landscape. One of the poem's subtexts speaks to Africans’ political, economic, and cultural rights, and the disavowal, refusal, or lack of their recognition. Ancient histories of exchange resonate with the globalised present, as the young men of De Kok's poem are saturated, not only in Venice's celebrated light, but also in relations of power that span time and place, and are imbricated with the markers of culture invoked by the poem's descriptions as well as by its title:

Merchants in Venice

We arrive in Venice to ancient acoustics:

the swaddling of paddle in water,

thud of the vaporetto against the landing site,

and the turbulent frescoes of corridors and ceilings,

belief and power sounding history

with the bells of the subdivided hour,

on water, air and all surfaces of light.

What have we Africans to do with this?

With holy water, floating graves and cypresses,

the adamantine intricacy of marble floors,

gold borders of faith, Mary's illuminated face

and the way Tintoretto's Crucifixion is weighted

with the burden of everyday sin and sweat,

while the city keeps selling its history and glass.

On the Rialto, tourists eye the wares

of three of our continent's diasporic sons,

young men in dreadlocks and caps, touting

leather bags and laser toys in the subdued dialect

of those whose papers never are correct,

homeboys now in crowded high-rise rooms

edging the embroidered city.

How did they get from Dakar to Venice?

What brotherhood sent them to barter and pray?

And on long rainy days when the basilica

levitates, dreaming of drowning,

do they think of their mission and mothers,

or hover and hustle like apprentice angels

over the shrouded campos and spires?

Into the city we have come for centuries,

buyers, sellers, mercenaries, spies,

artists, saints, the banished,

and boys like these: fast on their feet,

carrying sacks of counterfeit goods,

shining in saturated light,

the mobile inheritors of any renaissance.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

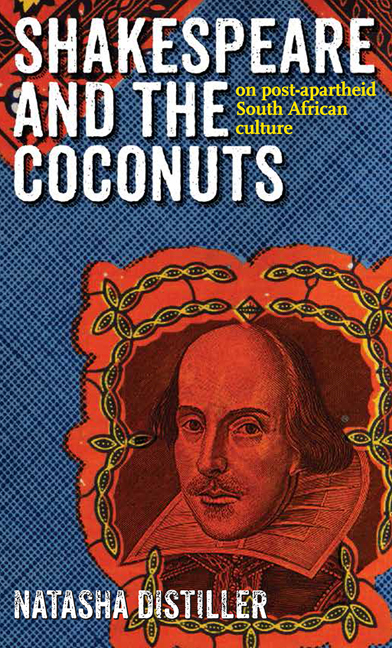

- Shakespeare and the Coconutson post-apartheid South African culture, pp. 1 - 18Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2012