Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Shakespeare in English, English in South Africa

- Chapter 2 ‘Through Shakespeare's Africa’: ‘Terror and murder’?

- Chapter 3 Tony's Will: Titus Andronicus in South Africa, 1995

- Chapter 4 Begging the questions: Producing Shakespeare for post-apartheid South African schools

- Chapter 5 English and the African Renaissance

- Chapter 6 Shakespeare and the coconuts

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- Index

Chapter 5 - English and the African Renaissance

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 April 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Shakespeare in English, English in South Africa

- Chapter 2 ‘Through Shakespeare's Africa’: ‘Terror and murder’?

- Chapter 3 Tony's Will: Titus Andronicus in South Africa, 1995

- Chapter 4 Begging the questions: Producing Shakespeare for post-apartheid South African schools

- Chapter 5 English and the African Renaissance

- Chapter 6 Shakespeare and the coconuts

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Reporting on his expulsion from the presidency in 2008, the Christian Science Monitor headed the story of Mbeki's downfall, ‘Thabo Mbeki: The Fall of Africa's Shakespearean Figure’. Scott Baldauf reports in terms that will become more familiar to us in the next chapter: Mbeki's intelligence, which went together with his aloofness, is contrasted to Zuma's ‘populism’. Not surprisingly, Mbeki's intelligence and aloofness are both associated with Shakespeare, here and elsewhere. What is notable here is that, just as Can Themba and Bloke Modisane explicitly do, and as critics have done with Plaatje, Mbeki self-identifies as a Shakespearean tragic hero. Interviewing his biographer, Mark Gevisser, Baldauf writes:

Mark Gevisser reveals that Mbeki, as a young economics student at the Lenin Institute in Moscow in 1969, closely identified with the tragic Shakespearean character, Coriolanus. Mbeki saw Coriolanus as a revolutionary role model who was prepared to go to war with his own people to defend the nation's principles. In the end, Coriolanus is exiled because of his unwillingness to publicly parade after returning from a successful campaign.

Mr. Gevisser suggested that Mbeki saw his own future in Coriolanus. ‘The person who does good, and does it honestly, must expect to be overpowered by forces of evil,’ he told Gevisser during a 1999 interview. ‘But it would be incorrect not to do good just because you know death is coming.’

The article ends on this note, a wholly sympathetic one, which allows Mbeki his identification and his self-expression as a great, if tragically wronged, character. He has been much less sympathetically treated in the media, specifically with regard to his penchant for Shakespeare. Mbeki's association with Shakespeare and its meaning in the popular imagination will be treated in more detail in the following chapter. In this chapter I look in some detail at how the coconut president's notion of the African Renaissance encodes the very revised meaning of coconuttiness I have been offering. It is no coincidence that it took a coconut to activate the notion, given its links to the idea of Renaissance upon which Shakespeare's popular reputation to some extent depends, and to the role of English Literature in developing this idea of Renaissance.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

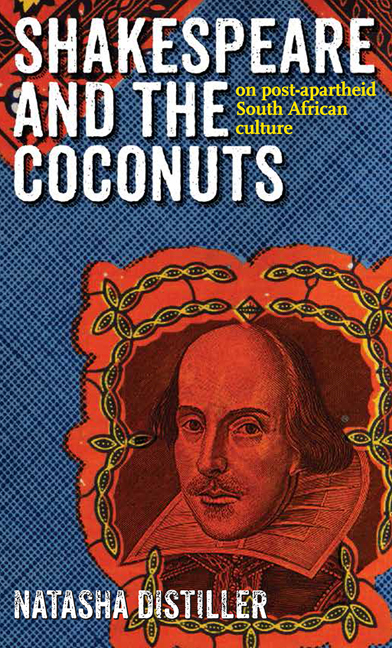

- Shakespeare and the Coconutson post-apartheid South African culture, pp. 125 - 142Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2012