Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on contributors

- Note on the text

- 1 Introduction

- PART 1 SHAKESPEARE'S CHILDREN

- 2 Introduction: ‘What, are they children?’

- 3 Little princes: Shakespeare's royal children

- 4 Father-child identification, loss and gender in Shakespeare's plays

- 5 Character building: Shakespeare's children in context

- 6 Coriolanus and the little eyases: the boyhood of Shakespeare's hero

- 7 Procreation, child-loss and the gendering of the sonnet

- PART 2 CHILDREN'S SHAKESPEARES

- APPENDICES

- Index

4 - Father-child identification, loss and gender in Shakespeare's plays

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 September 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on contributors

- Note on the text

- 1 Introduction

- PART 1 SHAKESPEARE'S CHILDREN

- 2 Introduction: ‘What, are they children?’

- 3 Little princes: Shakespeare's royal children

- 4 Father-child identification, loss and gender in Shakespeare's plays

- 5 Character building: Shakespeare's children in context

- 6 Coriolanus and the little eyases: the boyhood of Shakespeare's hero

- 7 Procreation, child-loss and the gendering of the sonnet

- PART 2 CHILDREN'S SHAKESPEARES

- APPENDICES

- Index

Summary

‘Shakespeare's art’, wrote the critic C. L. Barber, ‘is distinguished by the intensity of its investment in the human family, and especially in the continuity of the family across generations.’ But in the theatre, as historically, such continuity is fragile, for parents cannot always ensure their children's survival or control their choices. Still, for parents in Shakespeare, the relationship to their children is dramatized as crucial to their own identity. Throughout Shakespeare's career, one of the most recurrent constellations of themes is a father's identification with a child, particularly with a daughter, followed by some kind of loss of that child, whether to death or to marriage. This father-child relation often contributes to a central conflict of the play, as well as to its greatest emotional intensity. The plays suggest that emotions related both to having children and to having memories of childhood are central to the identities of many of the characters.

While childhood in most of the chapters in this volume is a matter of age, the word ‘child’ is ambiguous; it can also apply to persons of all ages in relation to their parents. In many cultures parents' experiences of young children as their dependants and even possessions may continue to affect parental perceptions of offspring even after the children have become adults. Such dynamics also influence some adult children's attitudes toward their parents.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

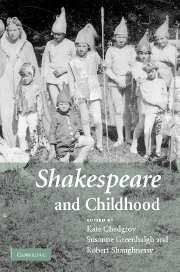

- Shakespeare and Childhood , pp. 49 - 63Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2007

- 5

- Cited by