Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Cases

- List of Statutes

- About the Authors

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction: Setting the Scene

- 2 A History of Rape Law in Action

- 3 Emergence of a Legal Regime Governing the Use of Sexual History Evidence

- 4 Legal Regulation: Limits and Potentialities

- 5 Tracking the Use of Sexual History Evidence in the Courtroom

- 6 The Relevance of Sexual History Evidence

- 7 Sexual History Evidence and Subjectivity

- 8 Conclusion: What Is to Be Done about Sexual History Evidence?

- References

- Index

8 - Conclusion: What Is to Be Done about Sexual History Evidence?

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 03 April 2024

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Cases

- List of Statutes

- About the Authors

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction: Setting the Scene

- 2 A History of Rape Law in Action

- 3 Emergence of a Legal Regime Governing the Use of Sexual History Evidence

- 4 Legal Regulation: Limits and Potentialities

- 5 Tracking the Use of Sexual History Evidence in the Courtroom

- 6 The Relevance of Sexual History Evidence

- 7 Sexual History Evidence and Subjectivity

- 8 Conclusion: What Is to Be Done about Sexual History Evidence?

- References

- Index

Summary

Rape, law and justice revisited

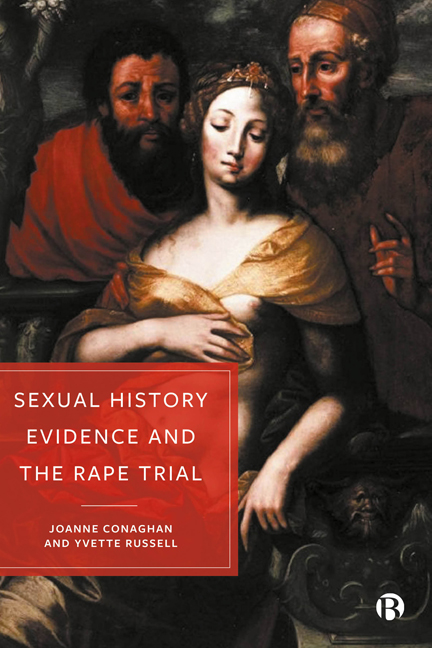

The image that adorns the cover of this book is a reproduction of ‘Susanna and the Elders’ by the Flemish Renaissance painter Vincent Sellaer, thought to have been composed in the first half of 16th century. Susanna’s story is one to which we were drawn because it is a story of sexual violence and law, in which several of the motifs we discuss in this book surface. The story, which appeared first in the Old Testament Apocrypha and is thought to have been written around the 2nd century BC (Moore, 1977: 92), is set in Babylon during the Exile. Susanna was the wife of a prominent Jewish community member and was observed bathing by two passing elders, who accosted her when she was alone, having been overcome by their lust for her. The elders threatened her with humiliation by publicly accusing her of adultery if she denied their requests for sex. Susanna ‘courageously refused to commit this sin against God’, and when the elders carried through with their threats, she was arrested, tried, convicted and sentenced to death (Bohn, 2001: 260). Susanna was never asked for her version of the events, and she never volunteered it (Glancy, 1993: 115; Bohn, 2001: 260). Before Susanna’s sentence could be carried out, the future prophet Daniel interceded on her behalf, testifying to her virtue and demanding that the elders be cross-examined. The inconsistencies in their testimony, drawn out by Daniel’s questioning, revealed their lies, and Susanna was exonerated. The elders were stoned to death in Susanna’s place. As the biblical scholar Babette Bohn points out, Susanna’s story is usually understood as one that situates the importance of fidelity, both to God and the bonds of marriage, and illustrates the value and efficacy of prayer (Bohn, 2001: 260). However, it is also a story about law, gender and justice.

While there are many artistic representations of Susanna and her story in period artwork, we were drawn to this image in part for its composition and colours, but also because it captures the oppressive essence of this part of Susanna’s story (the attempted rape or ‘seduction’), and of what we perceive it must be like to be a rape complainant giving evidence in the courtroom.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Sexual History Evidence and the Rape Trial , pp. 184 - 198Publisher: Bristol University PressPrint publication year: 2023