Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acronyms

- Chapter 1 Rock art with and without ethnography

- Chapter 2 Flashes of brilliance: San rock paintings of heaven's things

- Chapter 3 Snake and veil: The rock engravings of Driekopseiland, Northern Cape South Africa

- Chapter 4 Cups and saucers: A preliminary investigation of the rock carvings of Tsodilo Hills, northern Botswana

- Chapter 5 Art and authorship in southern African rock art: Examining the Limpopo-Shashe Confluence Area

- Chapter 6 Archaeology, ethnography, and rock art: A modern-day study from Tanzania

- Chapter 7 Art and belief: The ever-changing and the never-changing in the Far west

- Chapter 8 Crow Indian elk love-medicine and rock art in Montana and Wyoming

- Chapter 9 Layer by layer: Precision and accuracy in rock art recording and dating

- Chapter 10 From the tyranny of the figures to the interrelationship between myths, rock art and their surfaces

- Chapter 11 Composite creatures in European Palaeolithic art

- Chapter 12 Thinking strings: On theory, shifts and conceptual issues in the study of Palaeolithic art

- Chapter 13 Rock art without ethnography? A history of attitude to rock art and landscape at Frøysjøen, western norway

- Chapter 14 ‘Meaning cannot rest or stay the same’

- Chapter 15 Manica rock art in contemporary society

- Chapter 16 Oral tradition, ethnography, and the practice of north American archaeology

- Chapter 17 Beyond rock art: Archaeological interpretation and the shamanic frame

- List of figures

- List of tables

- List of publications by david Lewis-williams

- Index

Chapter 11 - Composite creatures in European Palaeolithic art

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 April 2018

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acronyms

- Chapter 1 Rock art with and without ethnography

- Chapter 2 Flashes of brilliance: San rock paintings of heaven's things

- Chapter 3 Snake and veil: The rock engravings of Driekopseiland, Northern Cape South Africa

- Chapter 4 Cups and saucers: A preliminary investigation of the rock carvings of Tsodilo Hills, northern Botswana

- Chapter 5 Art and authorship in southern African rock art: Examining the Limpopo-Shashe Confluence Area

- Chapter 6 Archaeology, ethnography, and rock art: A modern-day study from Tanzania

- Chapter 7 Art and belief: The ever-changing and the never-changing in the Far west

- Chapter 8 Crow Indian elk love-medicine and rock art in Montana and Wyoming

- Chapter 9 Layer by layer: Precision and accuracy in rock art recording and dating

- Chapter 10 From the tyranny of the figures to the interrelationship between myths, rock art and their surfaces

- Chapter 11 Composite creatures in European Palaeolithic art

- Chapter 12 Thinking strings: On theory, shifts and conceptual issues in the study of Palaeolithic art

- Chapter 13 Rock art without ethnography? A history of attitude to rock art and landscape at Frøysjøen, western norway

- Chapter 14 ‘Meaning cannot rest or stay the same’

- Chapter 15 Manica rock art in contemporary society

- Chapter 16 Oral tradition, ethnography, and the practice of north American archaeology

- Chapter 17 Beyond rock art: Archaeological interpretation and the shamanic frame

- List of figures

- List of tables

- List of publications by david Lewis-williams

- Index

Summary

IDENTIFYING COMPOSITE CREATURES

In Palaeolithic art, whether parietal or portable, composite creatures (anthropozoomorphs or therian thropes) are defined as “representations with mor pho logical characteristics indisputably attributable on the one hand to Man and on the other hand to Beast” (Clottes 1993: 198). When they were re-evaluated within the framework of the systematic general survey of the Groupe de Réflexion sur l´Art Pariétal Paléolithique (GRAPP 1993) on the theme of ‘methodology’, we took the narrowest definition. In effect, we accepted neither ‘phantoms’, where Leroi- Gourhan (1965: 96–97) saw a deliberate ambiguity between humans and birds or other animals, nor humans with prognathous heads, even though Leroi- Gourhan (1965: 96) admitted that in this case a “certai n pursuit of animal likeness” cannot be excluded. We omitted both the bird-headed humans in the shaft at Lascaux and at Altamira, and the frogheaded ones at Los Casares. Our objection at that time was that “too many human heads are wilfully deformed and [that] one finds so many intermediaries between the most realistic human heads and those with characteristics of an animal that it is difficult to draw an unequivocal line when dealing with representations that are relatively lacking in detail” (Clottes 1993: 198). As a result, the GRAPP list of parietal composite creatures was very short, with only seven individuals in three caves: three at Gabillou, three at Trois-Frères and one at Hornos de la Peña. In the portable art were mentioned those observed at Espélugues, at Enlène, at Tuc-d'Audoubert, and at Hohlenstein-Stadel in Germany. We could have quoted others such as the ‘little devils’ of l'Abri Mège at Teyjat (Dordogne) (Capitan et al. 1909: 72, figure 11).

Strict restraint justified our position within the framework of a work explicitly dedicated to methods where rigorous steps must be taken to determine such and such a figure and to classify it within a precise category only if the identification is certain. It is too easy to move from ‘probable’ or even ‘possible’ to ‘certain’ the moment statistics are compiled (Clottes 1989). Furthermore, it was clearly indicated that the elimination of heads which had been distorted, voluntarily resulted from difficulties in determining an obvious boundary between categories.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

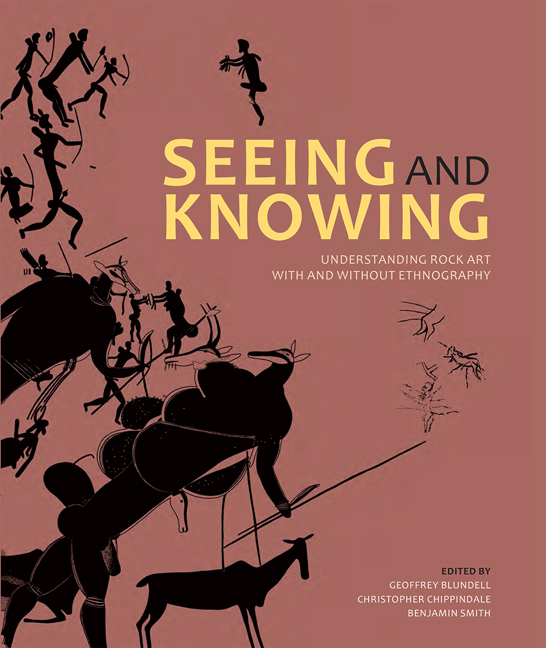

- Seeing and KnowingUnderstanding Rock Art With and Without Ethnography, pp. 188 - 197Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2010