Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Map

- Foreword

- PART 1 Introduction: Africa is Seldom What It Seems

- PART 2 Introduction: Fossils and Genes: A New Anthropology of Evolution

- PART 3 Introduction: The Emerging Stone Age

- PART 4 Introduction: The Myth of the Vacant Land

- PART 5 Introduction: The Racial Paradox: Sterkfontein, Smuts and Segregation

- Epilogue: Voice of Politics, Voice of Science: Politics and Science After 1945

- Notes, references and recommended reading

- Notes on contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Index

Epilogue: Voice of Politics, Voice of Science: Politics and Science After 1945

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 31 May 2019

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Map

- Foreword

- PART 1 Introduction: Africa is Seldom What It Seems

- PART 2 Introduction: Fossils and Genes: A New Anthropology of Evolution

- PART 3 Introduction: The Emerging Stone Age

- PART 4 Introduction: The Myth of the Vacant Land

- PART 5 Introduction: The Racial Paradox: Sterkfontein, Smuts and Segregation

- Epilogue: Voice of Politics, Voice of Science: Politics and Science After 1945

- Notes, references and recommended reading

- Notes on contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Index

Summary

The post-Second World War period witnessed tumultuous change in South Africa. Some of this arose in the realm of palaeontological research. In 1942 Broom had recognised at least part of the antiquity of the Cradle hominids and formations. In 1946, with the support of Smuts, he published his Transvaal Museum memoir which finally convinced the world that Africa represented the birthplace of humankind. In 1947 he exposed the most important hominid specimen to be found since the Taung skull, the fossil hominid that became known as ‘Mrs Ples’. South Africa, in palaeontological terms, was on the crest of a wave. Public and official recognition followed, but was soon brought to a precipitate end as both Afrikaner and African nationalism flexed their muscles and came into collision. In 1948 Afrikaner nationalists swept to power; their National Party would stay in office as the country's controlling political force for the next forty-six years. They came armed with the programme of apartheid or full-scale racial separation. Whereas the inter-war generation of South African politicians had subscribed to a policy of a common white South Africanism, which Smuts in particular sought to anchor in the achievements of a white South African science, the Nationalists narrowed their angle of vision to focus on an Afrikaner ‘volk’ or nation whom they promoted as God's chosen race. Apartheid looked for intellectual credentials elsewhere – in eugenics, in intelligence testing, but above all in what Loubser (1987) and Dubow (1992) term ‘the Apartheid Bible’.Afrikaner theologians and intellectuals ransacked the Old and New Testaments to provide an ideological rationalisation for racial separation and white supremacy. At the core of the argument that emerged, as Dubow shows, is the notion of God as ‘Hammabdil’, the Great Divider, separating light from dark, Heaven from Earth, men from women, nation from nation. The core text of this new theology was that section of the Old Testament that describes the Tower of Babel. Here God intervenes to disperse the builders of the Tower who wish to create a single nation, by causing them to speak mutually incomprehensible languages. On a different continent and in a different context, Afrikaner nationalists were now repeating this act and observing God's will (Dubow 1992). From this point on, science and public political discourse proceeded on two divergent paths.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

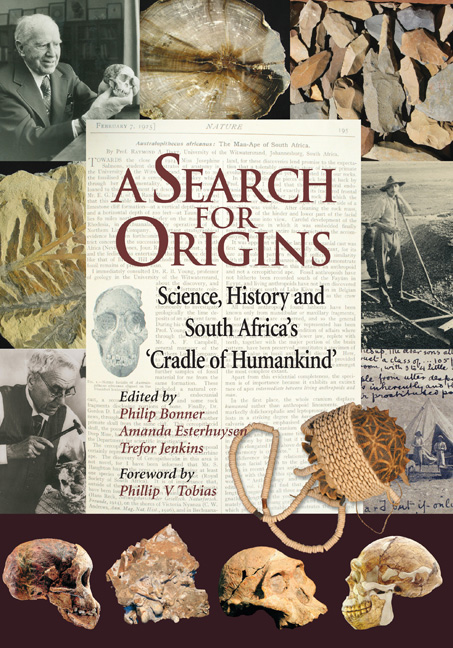

- A Search for OriginsScience, History and South Africa's ‘Cradle of Humankind’, pp. 275 - 278Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2007