Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1 Isabella d’Este's Sartorial Politics

- 2 Dressing the Queen at the French Renaissance Court: Sartorial Politics

- 3 Dressing the Bride: Weddings and Fashion Practices at German Princely Courts in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries

- 4 Lustrous Virtue: Eleanor of Austria's Jewels and Gems as Composite Cultural Identity and Affective Maternal Agency

- 5 Queen Elizabeth: Studded with Costly Jewels

- 6 A ‘Cipher of A and C set on the one Syde with diamonds’: Anna of Denmark's Jewellery and the Politics of Dynastic Display

- 7 ‘She bears a duke's revenues on her back’: Fashioning Shakespeare's Women at Court

- 8 How to Dress a Female King: Manifestations of Gender and Power in the Wardrobe of Christina of Sweden

- 9 Clothes Make the Queen: Mariana of Austria's Style of Dress, from Archduchess to Queen Consort (1634–1665)

- 10 ‘The best of Queens, the most obedient wife’: Fashioning a Place for Catherine of Braganza as Consort to Charles II

- 11 Chintz, China, and Chocolate: The Politics of Fashion at Charles II's Court

- 12 Henrietta Maria and the Politics of Widows’ Dress at the Stuart Court

- Works Cited

- Index

5 - Queen Elizabeth: Studded with Costly Jewels

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 November 2020

- Frontmatter

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1 Isabella d’Este's Sartorial Politics

- 2 Dressing the Queen at the French Renaissance Court: Sartorial Politics

- 3 Dressing the Bride: Weddings and Fashion Practices at German Princely Courts in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries

- 4 Lustrous Virtue: Eleanor of Austria's Jewels and Gems as Composite Cultural Identity and Affective Maternal Agency

- 5 Queen Elizabeth: Studded with Costly Jewels

- 6 A ‘Cipher of A and C set on the one Syde with diamonds’: Anna of Denmark's Jewellery and the Politics of Dynastic Display

- 7 ‘She bears a duke's revenues on her back’: Fashioning Shakespeare's Women at Court

- 8 How to Dress a Female King: Manifestations of Gender and Power in the Wardrobe of Christina of Sweden

- 9 Clothes Make the Queen: Mariana of Austria's Style of Dress, from Archduchess to Queen Consort (1634–1665)

- 10 ‘The best of Queens, the most obedient wife’: Fashioning a Place for Catherine of Braganza as Consort to Charles II

- 11 Chintz, China, and Chocolate: The Politics of Fashion at Charles II's Court

- 12 Henrietta Maria and the Politics of Widows’ Dress at the Stuart Court

- Works Cited

- Index

Summary

Abstract

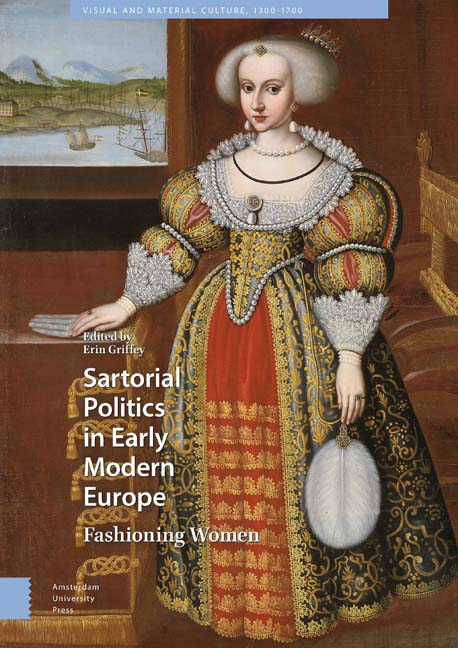

Queen Elizabeth I was the most bejewelled person in English history. While scholars have become appreciative of the care with which her image was crafted and the political purposes it served, the role that jewellery played has tended to be overlooked. This chapter discusses this important part of her wardrobe. It begins by taking an object-biographical approach, considering the composition, making, and wearing of elite jewellery in general. It turns then to Elizabeth's collection, examining the importance of gift-giving, the design of her jewels, and their potential symbolism and political function. Finally, it looks at the way Elizabeth's own image was incorporated into jewellery forms, and the process by which this gem-encrusted monarch was herself transformed into an icon.

Key words: Queen Elizabeth I; jewellery; symbolism; dress; Protestant; gift

Queen Elizabeth I was the most bejewelled person in the history of England. In a century whose portraits suggest an importance for male and female jewellery-wearing unmatched by previous or subsequent eras, Elizabeth's image stands out as saturated with gems and precious metals. Contemporaries also remarked this, particularly visiting foreigners. Paul Hentzner from Bradenburg, admitted to the presence chamber in the summer of 1598, wrote up the experience in his journal, describing the queen's ‘Necklace of exceeding fine jewels’, her white silk gown bordered with ‘pearls the size of beans’, and her ‘oblong Collar of gold and jewels’. Under her gloves, he wrote, she wore rings and jewels, so that when she raised her bare hand to be kissed, it sparkled. The following year Thomas Platter found her ‘gorgeously apparelled’, ‘lavishly attired’, and ‘studded with costly jewels’. Another description comes from Giovanni Carlo Scaramelli, a Venetian official whose 1603 letter reporting to the Doge recounts Elizabeth's appearance in the month before her death. Her throat was ‘encircled with pearls and rubies down to her breast’, and around her forehead were ‘great pearls like pears’. Indeed, Scaramelli said, the queen ‘displayed a vast quantity of gems and pearls upon her person; even under her stomacher she was covered with golden jewelled girdles and single gems, carbuncles, balas-rubies, diamonds; around her wrists in place of bracelets she wore double rows of pearls’.

The excess of these and similar descriptions, although seemingly hyperbolic, effectively render in words Elizabeth's portraits from the second half of her reign.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Sartorial Politics in Early Modern EuropeFashioning Women, pp. 115 - 138Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2019