Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1 Isabella d’Este's Sartorial Politics

- 2 Dressing the Queen at the French Renaissance Court: Sartorial Politics

- 3 Dressing the Bride: Weddings and Fashion Practices at German Princely Courts in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries

- 4 Lustrous Virtue: Eleanor of Austria's Jewels and Gems as Composite Cultural Identity and Affective Maternal Agency

- 5 Queen Elizabeth: Studded with Costly Jewels

- 6 A ‘Cipher of A and C set on the one Syde with diamonds’: Anna of Denmark's Jewellery and the Politics of Dynastic Display

- 7 ‘She bears a duke's revenues on her back’: Fashioning Shakespeare's Women at Court

- 8 How to Dress a Female King: Manifestations of Gender and Power in the Wardrobe of Christina of Sweden

- 9 Clothes Make the Queen: Mariana of Austria's Style of Dress, from Archduchess to Queen Consort (1634–1665)

- 10 ‘The best of Queens, the most obedient wife’: Fashioning a Place for Catherine of Braganza as Consort to Charles II

- 11 Chintz, China, and Chocolate: The Politics of Fashion at Charles II's Court

- 12 Henrietta Maria and the Politics of Widows’ Dress at the Stuart Court

- Works Cited

- Index

Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 November 2020

- Frontmatter

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1 Isabella d’Este's Sartorial Politics

- 2 Dressing the Queen at the French Renaissance Court: Sartorial Politics

- 3 Dressing the Bride: Weddings and Fashion Practices at German Princely Courts in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries

- 4 Lustrous Virtue: Eleanor of Austria's Jewels and Gems as Composite Cultural Identity and Affective Maternal Agency

- 5 Queen Elizabeth: Studded with Costly Jewels

- 6 A ‘Cipher of A and C set on the one Syde with diamonds’: Anna of Denmark's Jewellery and the Politics of Dynastic Display

- 7 ‘She bears a duke's revenues on her back’: Fashioning Shakespeare's Women at Court

- 8 How to Dress a Female King: Manifestations of Gender and Power in the Wardrobe of Christina of Sweden

- 9 Clothes Make the Queen: Mariana of Austria's Style of Dress, from Archduchess to Queen Consort (1634–1665)

- 10 ‘The best of Queens, the most obedient wife’: Fashioning a Place for Catherine of Braganza as Consort to Charles II

- 11 Chintz, China, and Chocolate: The Politics of Fashion at Charles II's Court

- 12 Henrietta Maria and the Politics of Widows’ Dress at the Stuart Court

- Works Cited

- Index

Summary

Fashion as Meaning: ‘the pattern of your imitation’

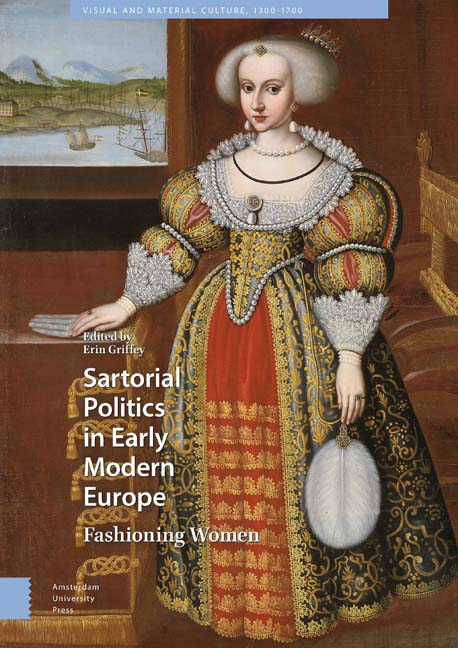

Writing in 1673, Hannah Woolley's The Gentlewoman's Companion; or, a Guide to the Female Sex advised women to ‘incline somewhat to the Mode of Court (which is the source and foundation of fashion); but let the example of the most sober, moderate, and modest be the pattern of your imitation’. Female clothing materialised both fashion and virtue, engagement with the court and with traditional female values. Medieval and early modern concepts of ‘costume’ and ‘habit’ embodied outer appearance or clothing as well as manners or moral qualities. As such, clothing was inherently powerful. It worked to link a person to the (fashionable) authority of the court, but it also had the potential (and limitations) of communicating personal morality.

Essentially, clothing embodied identity. As Ulinka Rublack states, clothing was not ‘something external to the body, that could be simply put on and taken off, or that could function as an abstract sign: rather, it was seen to mould a person and materialize identity’. Likewise, looking specifically to the early modern court, Ann Rosalind Jones and Peter Stallybrass trace the term ‘fashion’ to its Latin origin as the verb ‘to make’, or, in its biblical sense, ‘to create’, i.e., creating a self through their appearance. The power of clothing in creating an immediately recognisable identity was readily understood by early modern theatre companies who relied on dress to communicate character and social status in a symbiosis of inner and outer appearance. Rank, wealth, magnificence, and personal virtue was embodied in dress, and, as such, dress was inherently political, richly materialising the qualities associated with the wearer, whatever their rank.

Clothing necessitated careful selection across every aspect of the attired body – the choice of garment type, the fabric, the cut, the colour, the texture, and the decoration. This was based on the inherent dialectic in clothing between the subject and the observer, presentation and perception. At the early modern court, elites were keenly aware that they were always on display, performing and being observed, with Rublack characterising the social group as being ‘supremely dress-literate’. This was not new to the Renaissance, however, for it was in strong evidence at the medieval court where, as Susan Crane states, the secular elite understood ‘themselves to be constantly on display, subject to the judgment of others, and continually reinvented in performance’.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Sartorial Politics in Early Modern EuropeFashioning Women, pp. 15 - 32Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2019