Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

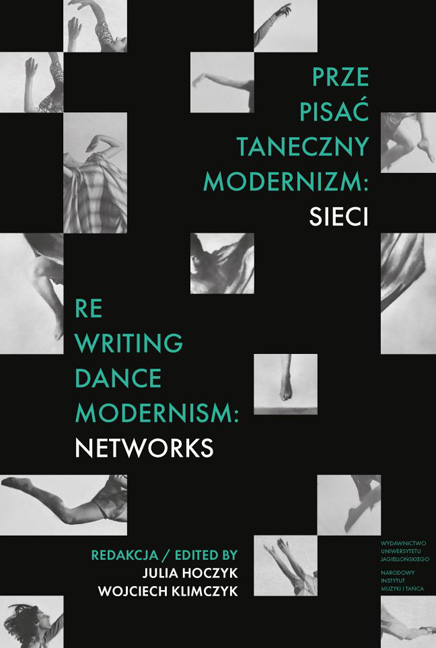

- Prze-pisać taneczny modernizm: sieci

- Metodologie: usieciowianie tanecznego modernizmu

- Transmisje: transnarodowe trajektorie tanecznego modernizmu

- Poszerzenia: taneczny modernizm w słowiańskiej Europie Środkowej

- Methodologies: Networking Dance Modernism

- Transmissions: Transnational Trajectories of Dance Modernism

- Expansions: Dance Modernism in Slavic Central Europe

- Biogramy autorów

- Authors’ Biographies

- Indeks / Index

- Miscellaneous Endmatter

- Miscellaneous Endmatter

Polish – Ours / Foreign – Alien – Stranger. The 1933 International Artistic Dance Competition in Warsaw’s Press

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 March 2024

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Prze-pisać taneczny modernizm: sieci

- Metodologie: usieciowianie tanecznego modernizmu

- Transmisje: transnarodowe trajektorie tanecznego modernizmu

- Poszerzenia: taneczny modernizm w słowiańskiej Europie Środkowej

- Methodologies: Networking Dance Modernism

- Transmissions: Transnational Trajectories of Dance Modernism

- Expansions: Dance Modernism in Slavic Central Europe

- Biogramy autorów

- Authors’ Biographies

- Indeks / Index

- Miscellaneous Endmatter

- Miscellaneous Endmatter

Summary

Introduction

“Words create the reality.” Attributed to Paul Ricoeur, this popular saying encapsulates the foundations of cognitivism, which was initiated as a trend in linguistics and gradually expanded its analytical reach over other fields of the humanities. How one designates phenomena, what words one uses to define other people, and how one describes events, are all indicative of one's worldview: a system of convictions organizing one's reality. The way in which one formulates one's utterances reveals a lot about one's reading preferences, one's key values, and one's perception of how a given topic is construed by those listening to or reading a certain opinion. The impact of one's language on other people's perceptions is particularly powerful in journalistic texts or commentaries. The press has a wide reach, and published commentators are often considered as pundits in their respective fields; hence, it is all the easier to unreflectively internalize the designations and convictions embedded in their texts.

This article aims to expound the ways in which Warsaw's press described the 1933 International Artistic Dance Competition, while also attempting to reconstruct the image of dance and dancers emerging from the journalists’ attitude towards the performers’ nationalities. How did they define the “Polishness” of a given dance or a person who performed it? What criteria determined if the performer's nationality was perceived as (non)Polish? Were the competition participants’ declarations taken into consideration? Did their birthplace, domicile, educational background and previous stage career matter? Was the same language used to review domestic and foreign artists? Did commentators write in their own, individual styles, or were their linguistic choices linked to the profiles of their respective newspapers? While the scope of editorial interventions in the published texts cannot be determined, one is nonetheless tempted to address the above questions by approaching the preserved materials as a testimony to the worldview (or rather: worldviews) prevailing in Poland at that time, not only with respect to dance. The 1930s in Europe were a period of a political calm before the storm whose social (and linguistic) heralds only seem obvious ex post.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Re-writing Dance Modernism: Networks , pp. 557 - 578Publisher: Jagiellonian University PressPrint publication year: 2023