Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on contributors

- Introduction

- PART I VOICES AND EXPERIENCES

- PART II PERCEPTIONS AND PROXIMITIES

- 6 Representing Otherness: African, Indian and European soldiers' letters and memoirs

- 7 Living apart together: Belgian civilians and non-white troops and workers in wartime Flanders

- 8 Nursing the Other: the representation of colonial troops in French and British First World War nursing memoirs

- 9 Imperial captivities: colonial prisoners of war in Germany and the Ottoman empire, 1914–1918

- 10 Images of Te Hokowhitu A Tu in the First World War

- PART III NATIONALISM, MEMORY AND LITERATURE

- Index

- References

8 - Nursing the Other: the representation of colonial troops in French and British First World War nursing memoirs

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2014

- Frontmatter

- Contents

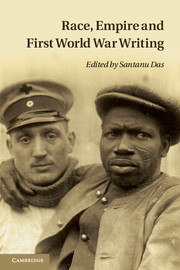

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on contributors

- Introduction

- PART I VOICES AND EXPERIENCES

- PART II PERCEPTIONS AND PROXIMITIES

- 6 Representing Otherness: African, Indian and European soldiers' letters and memoirs

- 7 Living apart together: Belgian civilians and non-white troops and workers in wartime Flanders

- 8 Nursing the Other: the representation of colonial troops in French and British First World War nursing memoirs

- 9 Imperial captivities: colonial prisoners of war in Germany and the Ottoman empire, 1914–1918

- 10 Images of Te Hokowhitu A Tu in the First World War

- PART III NATIONALISM, MEMORY AND LITERATURE

- Index

- References

Summary

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, both French and British commentators began to view white middle-class women as an increasingly important element of the ‘civilising mission’ of the colonial enterprise. In an 1899 address to the Colonial Nursing Association, Sir George Goldie, governor of the Royal Niger Company, spoke for many when he labelled the work of European nurses in British West African colonies as the ‘white woman's burden’; a year later, French Jesuit priest Jean-Baptiste Piolet wrote in relation to French colonialism that ‘woman is made to civilize and police, to inspire and purify, to elevate and exalt all that surrounds her’. At the same time, the presence of white women in the colonies was seen to be fraught with dangers, especially in terms of the protection of ‘white prestige’, a central component of imperial discourse. White women in the colonies were expected to conform to an idealised model of sexually pure and morally virtuous femininity and were criticised if they were perceived to have failed to do so – some of the nurses Goldie addressed in 1899, for example, were subsequently accused of improper appearance and sexual impropriety, and requests were made for lady nurses ‘of mature years and less attractive appearance’. Further it was equally assumed that their presence left them sexually vulnerable to the ‘uncontrolled’ sexuality and ‘primitive urges’ of the colonised men.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Race, Empire and First World War Writing , pp. 158 - 174Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2011

References

- 5

- Cited by