Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on contributors

- Introduction

- PART I VOICES AND EXPERIENCES

- PART II PERCEPTIONS AND PROXIMITIES

- PART III NATIONALISM, MEMORY AND LITERATURE

- 11 ‘He was black, he was a White man, and a dinkum Aussie’: race and empire in revisiting the Anzac legend

- 12 The quiet Western Front: the First World War and New Zealand memory

- 13 ‘Writing out of opinions’: Irish experience and the theatre of the First World War

- 14 ‘Heaven grant you strength to fight the battle for your race’: nationalism, Pan-Africanism and the First World War in Jamaican memory

- 15 Not only war: the First World War and African American literature

- Afterword Death and the afterlife: Britain's colonies and dominions

- Index

- References

14 - ‘Heaven grant you strength to fight the battle for your race’: nationalism, Pan-Africanism and the First World War in Jamaican memory

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2014

- Frontmatter

- Contents

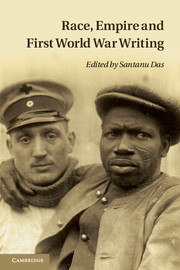

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on contributors

- Introduction

- PART I VOICES AND EXPERIENCES

- PART II PERCEPTIONS AND PROXIMITIES

- PART III NATIONALISM, MEMORY AND LITERATURE

- 11 ‘He was black, he was a White man, and a dinkum Aussie’: race and empire in revisiting the Anzac legend

- 12 The quiet Western Front: the First World War and New Zealand memory

- 13 ‘Writing out of opinions’: Irish experience and the theatre of the First World War

- 14 ‘Heaven grant you strength to fight the battle for your race’: nationalism, Pan-Africanism and the First World War in Jamaican memory

- 15 Not only war: the First World War and African American literature

- Afterword Death and the afterlife: Britain's colonies and dominions

- Index

- References

Summary

In 1981 the Iran–Iraq war (1980–8) had become mired in the trench warfare and gas attacks of an earlier era. The Jamaican writer John Hearne was moved to reflect on the nature and impact of twentieth-century warfare. Although he had been born eight years after the Armistice, the First World War had loomed as a ‘grey fear’ for Hearne, a stain on his childhood representing the abiding anxiety that his father, twice wounded in the conflict, would heed another call of Empire and not return. This overwhelming anticipation of loss marred an otherwise idyllic journey from boy to man, which Hearne often spent in the company of a father he clearly adored. His upbringing in the higher reaches of Jamaican society was reflected in a nostalgia for mountain treks, horse riding, cricket and boxing, pastimes Hearne enjoyed during a decade of smouldering resentment at colonial rule which exploded in the 1938 labour rebellion. But Hearne's race and class interests were outweighed by more universal concerns. The imagined death of his father in some future war represented a lost innocence: a personal symbol for the millions Hearne believed had needlessly died in the name of ‘religions, political ideologies and national sovereignties’ during the twentieth century.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Race, Empire and First World War Writing , pp. 265 - 282Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2011