Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on contributors

- Introduction

- PART I VOICES AND EXPERIENCES

- PART II PERCEPTIONS AND PROXIMITIES

- PART III NATIONALISM, MEMORY AND LITERATURE

- 11 ‘He was black, he was a White man, and a dinkum Aussie’: race and empire in revisiting the Anzac legend

- 12 The quiet Western Front: the First World War and New Zealand memory

- 13 ‘Writing out of opinions’: Irish experience and the theatre of the First World War

- 14 ‘Heaven grant you strength to fight the battle for your race’: nationalism, Pan-Africanism and the First World War in Jamaican memory

- 15 Not only war: the First World War and African American literature

- Afterword Death and the afterlife: Britain's colonies and dominions

- Index

- References

Afterword Death and the afterlife: Britain's colonies and dominions

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2014

- Frontmatter

- Contents

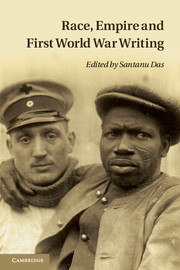

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on contributors

- Introduction

- PART I VOICES AND EXPERIENCES

- PART II PERCEPTIONS AND PROXIMITIES

- PART III NATIONALISM, MEMORY AND LITERATURE

- 11 ‘He was black, he was a White man, and a dinkum Aussie’: race and empire in revisiting the Anzac legend

- 12 The quiet Western Front: the First World War and New Zealand memory

- 13 ‘Writing out of opinions’: Irish experience and the theatre of the First World War

- 14 ‘Heaven grant you strength to fight the battle for your race’: nationalism, Pan-Africanism and the First World War in Jamaican memory

- 15 Not only war: the First World War and African American literature

- Afterword Death and the afterlife: Britain's colonies and dominions

- Index

- References

Summary

Jane Urquhart's remarkable novel The Stone Carvers (2002) imagines a young woman, of European wood-carving ancestry, travelling to Vimy in northern France from a village near Hamilton, Ontario. Disguised as a man, she obtains work on the Canadian monument and early one morning she steals into the workshop to carve the face of one of Walter Allward's allegorical figures in the image of her dead lover Eamonn. When Allward discovers her, he is angry that she has ‘ruined’ his torchbearer, explaining ‘he had wanted this stone youth to remain allegorical, universal, wanted him to represent everyone's lost friend, everyone's lost child’. Allward, we are told, ‘wanted the stone figure to be the 66,000 dead young men who had marched through his dreams when he had conceived the memorial’. But the face Klara was carving ‘had developed a personal expression’, it was ‘becoming a portrait’, and this had ‘never been his intention’. Confronted by this determined young woman, Urquhart's fictional Walter Allward realises that she has ‘allowed life’ to enter his monument and relents: ‘you can finish carving his face’, he agrees.

Klara Becker's desire to impose the face of one particular young man onto the body of Allward's universal young man can be seen as a metaphor for the philosophy of commemoration that prevailed on the Western Front, and in Europe generally, after the war.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Race, Empire and First World War Writing , pp. 301 - 320Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2011

References

- 7

- Cited by