Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Reading dangerously: Phyllis, Dido, Ariadne, and Medea

- 2 Reading the future?: Hypsipyle, Medea, and Oenone

- 3 Benefits of communal writing: Canace and Hypermestra

- 4 A feminine reading of epic: Briseis and Hermione

- 5 Reading magically: Deianira and Laodamia

- 6 Reading like a virgin: Phaedra and Ariadne

- 7 Caveat lector: thoughts on gender and power

- Appendix: The authenticity (and “authenticity”) of Heroides 15

- Bibliography

- Index

- Index Locorum

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 September 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Reading dangerously: Phyllis, Dido, Ariadne, and Medea

- 2 Reading the future?: Hypsipyle, Medea, and Oenone

- 3 Benefits of communal writing: Canace and Hypermestra

- 4 A feminine reading of epic: Briseis and Hermione

- 5 Reading magically: Deianira and Laodamia

- 6 Reading like a virgin: Phaedra and Ariadne

- 7 Caveat lector: thoughts on gender and power

- Appendix: The authenticity (and “authenticity”) of Heroides 15

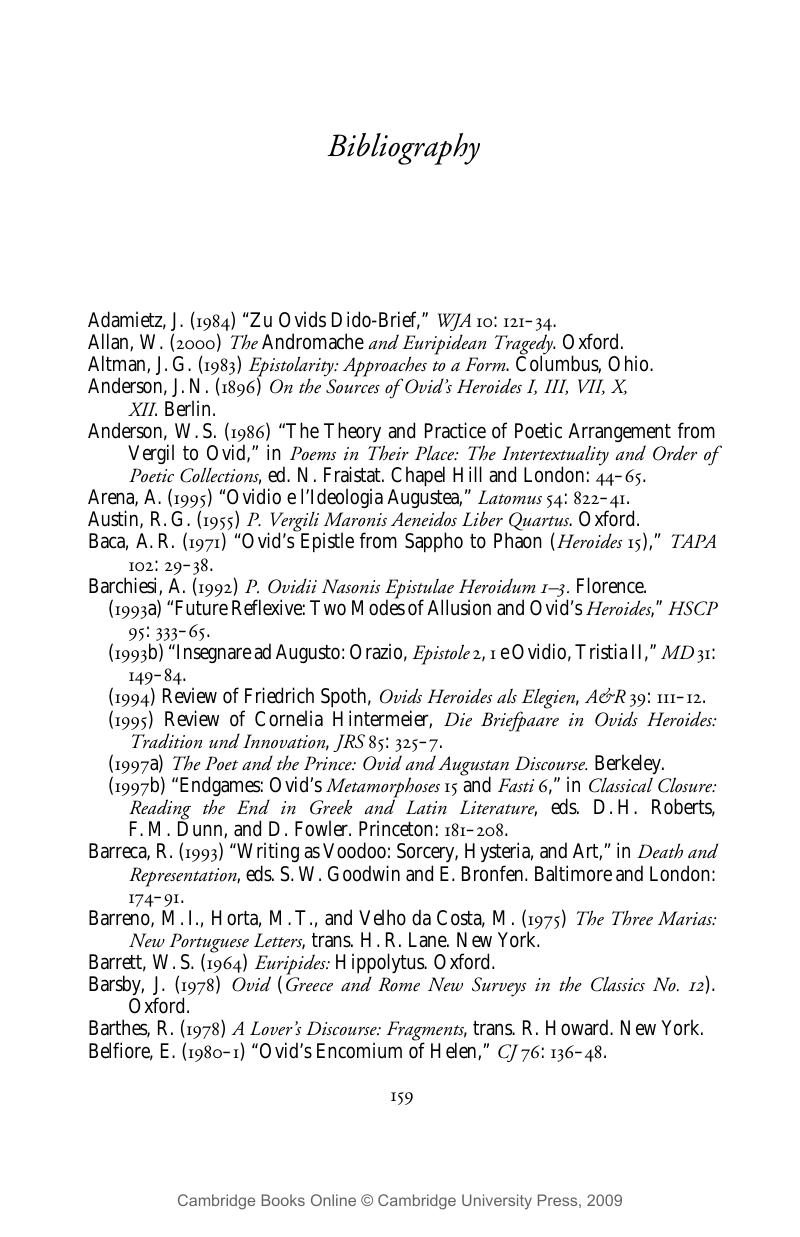

- Bibliography

- Index

- Index Locorum

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Ovidian Heroine as AuthorReading, Writing, and Community in the Heroides, pp. 159 - 170Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2005