Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: The second phase – tragedy or farce?

- PART 1 Party, Power and Class

- Introduction: Party, power and class

- Chapter 1 The power elite in democratic South Africa: Race and class in a fractured society

- Chapter 2 The ANC circa 2012-13: Colossus in decline?

- Chapter 3 Fragile multi-class alliances compared: Some unlikely parallels between the National Party and the African National Congress

- Chapter 4 Predicaments of post-apartheid social movement politics: The Anti-Privatisation Forum in Johannesburg

- PART 2 Ecology, Economy and Labour

- PART THREE Public Policy and Social Practice

- PART 4 South Africa at Large

- Contributors

- Index

Introduction: Party, power and class

from PART 1 - Party, Power and Class

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 31 May 2019

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: The second phase – tragedy or farce?

- PART 1 Party, Power and Class

- Introduction: Party, power and class

- Chapter 1 The power elite in democratic South Africa: Race and class in a fractured society

- Chapter 2 The ANC circa 2012-13: Colossus in decline?

- Chapter 3 Fragile multi-class alliances compared: Some unlikely parallels between the National Party and the African National Congress

- Chapter 4 Predicaments of post-apartheid social movement politics: The Anti-Privatisation Forum in Johannesburg

- PART 2 Ecology, Economy and Labour

- PART THREE Public Policy and Social Practice

- PART 4 South Africa at Large

- Contributors

- Index

Summary

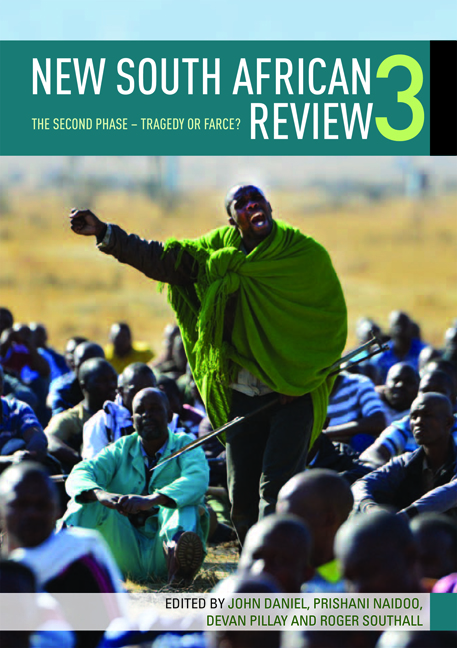

After nearly two decades of democracy, South Africa seems full of foreboding – a sense that somehow the country is approaching the end of the immediate post-liberation era and that political and economic uncertainty beckons. The indicators are many and well known. The global crisis of capitalism, and its impact upon the economy in terms of reduction of overseas markets and inflow of foreign investment, resulting in slower growth, absorbs government, the private sector and the media every day. In turn, the gloom is heightened by growing appreciation in even the rarified quarters of Sandton and Pretoria/Tshwane that democratic South Africa has failed to address fundamental structural features of the apartheid economy. Inequality may have deracialised to some degree but it remains extreme, and the vast majority of the population (especially black Africans) continue to struggle for a living and inhabit a world of poverty. The dire consequences these continuities may have for democracy and stability are increasingly recognised, as South Africa grapples with a revolt of the poor, epitomised most explicitly by the billowing of ‘service delivery protests’ (which in 2012 reached higher levels than in any year since 1994), and which record a multiplicity of social ills – but above all would seem to express not merely a demand to be heard and for accountability from government, but also a growing impatience with things as they are.

Those who wield political or economic power (or both), and those who live comfortably in middle-class homes, are becoming increasingly aware of the insistent demands of the majority. Perhaps we are approaching an era in which the poor come to be recognised in ruling circles as ‘the dangerous classes’, who threaten to bring the foundations of the established constitutional and political order crashing to the ground. Too dramatic? Too dystopian? Hopefully, yes. Nonetheless, it is difficult to contest analyses that predict the crumbling of democracy and warn of the dangers of a lurch towards political authoritarianism unless some sort of radical changes are undertaken. From the right, the call is for a massive shake-up of labour law, to lower the cost of South African labour, and thereby to attract a new inflow of private investment.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- New South African Review 3The second phase - Tragedy or Farce?, pp. 12 - 16Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2013